Addressing Childhood Obesity

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Obesity refers to the abnormal deposits of fat in the body which (may) result to poor health (World Health Organization (WHO), 2013). Thus childhood obesity (CHO) refers to an obese child. The description of what is obesity in children or obese children is problematic with some authors including generally overweight children as obese children while others excluding (Lobstein, Baur and Jackson-Leach, 2010). However, there is a general consensus that CHO is a health abnormality which has reached epidemic levels globally (WHO, 2007). The hardest hit regions being Europe and Americas. For those working on related research, healthcare dissertation help can provide valuable insights and support in navigating these complex issues.

CHO is as a result of many factors which determine its prevalence among certain clusters of children in any given society. Most of these factors are related to the socio-economic environment that these children are brought up (Noonan, 2018; Noonan et al., 2016). Scholars and policy makers have for long suggested that only a holistic and all-round approach would give the desired result in curbing CHO (HM Government, 2016). Although such an approach would be demanding to everyone in the community as well as the authorities, the result would help to save the (NHS) and families from imminent health risks posed by obesity.

2.0 STATISTICS

Globally, the CHO rate has been exponentially increasing for the last decade according to reports from as early as 2006 (Wang & Lobstein, 2006). Even in developing countries the experience is not much different save for it happens only in urban areas (Kambondo and Sartorius, 2018).

There is a well-founded fear of obesity in the United Kingdom. The rate, albeit having plateaued, is still in the epidemic levels (Royal Society for Public Health, 2015). As of the financial year 2015/2016, approximately a fifth of all 11-year olds in England were classified as obese (Hamblin, Fellowes and Clements, 2017). Those of around the age of 5 years and those of around grade 6 have registered 9.5% and 19.1% obesity rate respectively (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2014).

Continue your exploration of Access To Healthcare Services with our related content.

Overall, the obesity prevalence among children below the age of 15 years is at 33% or a third of their total population in England (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2015).

But the problem with CHO is not just with direct statistical analysis but also the acceptability by parents of information that their child (children) is obese. Indeed, 47% of parents in England do not believe that their children are obese (Park et al., 2013). However, this is also attributed to the rate of functional illiteracy among 20% of adults in the United Kingdom (National Literacy Trust, 2015) thus most of the parents do not comprehend the implications of CHO on the health of their children.

Continue your exploration of Metrics Indicators And Classifications In with our related content.

Whereas CHO rate has largely flattened in England, the same does not reflect in the least privileged areas as the rate of increase is much higher than in privileged areas of England (White, Rehkopf and Mortensen, 2016). Indeed the rate of increase in underprivileged areas was double that of children from privileged areas as of 2010 (Cole, Wardle and Stamatakis, 2010).

Thus interventions are needed more in those underprivileged areas than any other area in England albeit the interventions should be universal.

2.1 Economic Cost

According to GLA Intelligence Unit, 2011 the cost of CHO ought to be divided into two main categories: the direct cost of obesity and its associated problems; the indirect costs of obesity to the obese child.

Whereas there is no exact figure given as obesity is not treated per se rather it is the accompanying problems that pose the serious threat, in the financial year 2014/15 it was estimated that the cost of obesity for adults to the NHS was £5.4 billion (HM Government, 2016). The United Kingdom Chief Medical Officer estimated that the short-term costs of CHO were £ 51 million per year by 2012 whereas the long-term costs were approximately £ 700 million per year.

In London alone, the estimated total cost of CHO was £ 33.3 million every year while that for adults was 8% of the total budget of the Department of Health for London (GLA Intelligence Unit, 2011). It is estimated that the overall obesity cost for both adults and minors would be £ 50 billion per year by 2050 (Government Office for Science, 2007).

3.0 HEALTH DETERMINANTS FOR OBESITY

There are several factors associated with obesity at all levels but some are considered to be the most prevalent factors than others.

1. Sedentary living

This is synonymous to having reduced physical activity. Most children in England continue to engage in a lifestyle of lengthy periods of screen-time and staying in-house rather than engaging in outdoor activities (WHO, 2015). Compared with the 20th century, the amount of time spent by children watching television or playing video games has more than doubled; whereas an average of 3 hours were spent watching television in 1995, today children spend up to 6 hours in England (Childwise, 2015).

There is strong evidence to suggest that increased physical activity is associated with reduced CHO and the opposite is also true (Prentice-Dunn and Prentice-Dunn, 2012). Although the Chief Medical Officer recommends a minimum of 60 minutes of physical activity daily, barely do schools give more than two hours a week for physical activity (HM Government, 2016). This further contributed to the sedentary living at home.

2. Socio-economic condition

The inequitable distribution of State resources and the economic might of a group of people are an important determinant of CHO level (WHO, 2008). Indeed as previously highlighted, children hailing from underprivileged communities in England account for the highest number of cases of CHO (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2014).

For instance Liverpool which accounted for the most underprivileged people at 28% in any given city in England had the highest rate of obesity cases in the nation (Public Health England, 2018). The city, moreover, experienced a linear increase in obesity cases for the period between 2006 and 2012 according to studies conducted on children in the age of 5 years and grade 6 from the underprivileged community (Noonan, 2018).

It has been evidenced that communities from underserved areas have lesser choices of healthy diets thus resorting to taking fast foods which are cheaper to find and prepare (Noonan, 2018). Moreover, the lack of enough money makes the parents of these children to work longer hours thus reducing their parental time that would allow them to monitor the diet of their children.

Evidence suggests that since the 2008 financial crisis, the affordability of food for the underprivileged has gone down by a whopping 20% thus resulting to fewer choices of healthy diets (Defra, 2014).

Even in America, minority groups are bearing the blunt of the CHO epidemic as these groups usually account for the highest number of people with low income and living in the most underserved regions (Peña, Dixon and Taveras, 2012).

However, in developing countries the curve takes a different turn with children from high income families accounting for high cases of obesity as well as those coming from urban centres as compared to children from rural areas.

3. Dietary conditions

There is a global consensus that unhealthy diets contribute significantly to high levels of CHO. Indeed most of the interventions implemented in many OECD countries are aimed towards encouraging a healthy diet as an effective solution to obesity (Sassi, 2010). Even in schools, states worldwide are encouraging improved eating behaviour and healthy diet guidelines as a direct remedy to obesity (Lobelo et al., 2013). A WHO sub-organ strategic plan has an objective of improving healthy diet guidelines for Americas’ nations to curb the epidemic (Pan American Health Organization, 2015).

Even in the United States of America, close to 85% of pre-school children consume unhealthy diet in terms of high levels of sugar in sweetened beverages and foods (Fox et al., 2010).

Here in England, the rate of consumption of sugary beverages among teenagers was the highest in Europe as of 2010, (Brooks et al., 2010); hence further contributing to high rate of CHO in the United Kingdom. Thus it is no secret that obesity is a direct consequence of unhealthy diet.

4. Genetic conditions and biological factors

This is a very difficult factor to establish. Most researchers argue that obesity as a result of genetic relations occurs if the person concerned has led an unhealthy lifestyle (Ebbeling, Pawlak and Ludwig, 2002). It cannot be ruled out albeit it would only be a determinant if other factors such as sedentary living and unhealthy diet are involved.

Moreover, certain biological factors which may arise during pregnancy or after birth are associated with increased risk to CHO coupled with neurological factors which tend to influence overeating in human beings (Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care, 2012). However, there is little evidence to verify the exact extent of this determinant to CHO prevalence.

4.0 CHO IMPACT ON CHILDREN

Obesity is a public health problem as it exposes the obese person to a plethora of lifestyle diseases and health risks as well as other non-health factors. Thus the range of health risks associated with CHO is immense.

1. Health risks

The very first impact of CHO is that it exponentially increases the chances of being obese in adulthood as changing the status is a tedious and consuming task (Healthy Way to Grow Director, 2015). This then means that all health risks associated with obesity at adulthood are bound to occur at an even early age (Deckelbaum and Williams, 2001).

The consumption of excess sugars and sugary beverages increases the amount of calories in the body exponentially which is a direct source of Type 2 Diabetes and excessive weight in children (The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition, 2015). Indeed there is evidence to suggest that consumption of a 330ml soda alone would increase the chances of CHO drastically by exceeding the maximum limit of daily sugar intake (HM Government, 2016).

Accumulation of fat results to variety of cardiovascular diseases such as stroke, wide range of cancers, osteoarthritis among other diseases (Serdula et al., 1993 as cited in 2015).

Mental health issues may also develop due to stigmatization and bullying among peers which may eventually lead to suicide (Hamblin, Fellowes and Clements, 2017)

2. Non-health risks

Researchers have found evidence of poor academic performance among obese children. When obese children eventually grow into adulthood, it proves to be a limiting factor to securing jobs such as enrolment in the military.

Gable, Britt-Rankin and Krull, 2008 in a study comprising over 8000 children in the USA found that performance in mathematics and literature tests among obese girls was always significantly lower than girls who were never obese. Other prior studies such as that done by Datar and Sturm, 2006 which comprised of 7000 children in the USA, came to a similar conclusion albeit that it found little significance when other factors such as continuous obesity were put into consideration. Bottom line is that obese children tend to perform lower generally than normal-weight children.

5.0 SOCIO-ECOLOGICAL MODELS

There have been several approaches that have been implemented to counter the prevalence of CHO in England. These interventions have tested the various social models that can be relied upon to ensure elaborate and effective intervention on CHO. These socio-ecological models vary from school-based interventions to wholesome community models. Analysing them gives an important view of the barriers that are likely to be faced by any other model of intervention intended for adoption.

It has been suggested that a multi-component approach intervention which would incorporate schools, families and the community to ensure individual impact against CHO (WHO, 2012). The approach can be illustrated in the diagram below:

6.0 Health Promotion Framework

This is a socio-ecological model that has been proposed by the WHO. Its approach mainly focuses on providing proper health education to the children so as to discourage obesity-related behaviours (WHO, 1998). The model suggests several main pillars which must complement each other as a multi-component approach to obesity. These are; the school curriculum, the environment, family and community (Langford et al., 2015).

The program has proved to be effect in a wide-range of factors and in fighting obesity-related diseases such as Type 2 diabetes (Langford et al., 2014). Indeed Langford et al., 2015 conducted a study on over 67 intervention measures and studies that had implemented the program and all of them, despite having different modification, had proven effective when measured against the HPS original framework.

1. Mind Exercise Nutrition…. Do it! (MEND) Program

The MEND program is an initiative of Mytime Active developed in the United Kingdom. This approach pays particular impedance on family intervention on obesity by promoting physical activities and educating them on healthy dietary choices. Enrolment of the program is dependent on the local authorities who recommend and authorize involvement of underprivileged families in the United Kingdom (Hamblin, Fellowes and Clements, 2017). Thus the focal point of the approach is the family with the help of the local authorities but it does not include the school.

The authorities help in identify needy families experiencing cases of overweight children to be enrolled into the program. Scholars however have suggested that when the MEND program is enrolled via the voluntary community service groups, it becomes more effective (Sachers et al., 2010). This is coupled with evidence to suggest that the program is highly cost-effective (GLA Intelligence Unit, 2011).

2. The ‘Fat Letter’ Program

This is a controversial intervention measure which was set up in England in 2005 under the National Child Measurement Programme. Its aim was to provide annual data on the BMI of every child by measuring the BMI of every child yearly. The statistical benefit of the program has been to provide information on the rate of obesity in England (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2014).

As a means to add value to the process, the ‘fat letter’ service was initiated which delivers a letter to parents on the BMI of their child or children or allows the parents to collect such information from the local authorities if a letter is not delivered (Royal Society for Public Health, 2015). However, as it is done by the authorities, it has had minimal effect. This is because many parents do not understand the value of the information given as they probably do not have proper health education on the impact of CHO or they simply do not trust the findings of the authority (Statham, 2013). The national approach to the program also denies the State an opportunity to follow up with obese children towards reducing the rate of obesity.

3. Daily hour of physical activity

This is an intervention which solely focuses on the rate of physical activity of children in England. It arises from the recommendation given by the Chief Medical Officer that a child should have a minimum of 60 minutes of physical activity at school. However, most schools in England, as previously highlighted, have a reduced physical activity period on a weekly basis let alone daily (Sheldon and Elliot, 1999 as cited in 2015).

Many scholars have suggested that school physical activity alone would not be sufficient. Thus parents are encouraged to ensure their children to walk to school rather than take a bus ride (Royal Society for Public Health, 2015). As a result, less than 30% of English children engaged in the daily minimum 60-minute physical activity (Department of Health. 2011).

4. Healthy Way to Grow

In the United States of America, a multi-component programme dubbed the Healthy Way to Grow was initiated to serve as an intervention to CHO in America (American Heart Association, 2013). The programme comprises of key pillars that is educating both the children and their caretakers, providing healthy diet guidelines to schools, community institutions and families, discouraging sedentary lifestyles for children such as limiting screen time as well as partnering with local communities to encourage outdoor physical activities among others (Healthy Way to Grow Director, 2015).

6.0 SEARCH STRATEGY

The search strategy deployed was two-fold. There was systematic searching of PubMed and Academic Search Complete in search of obesity interventions studies. Secondly, there was a generalized search on Google documents and Google search engine using the following keywords;

1. Health education on childhood obesity

2. Childhood obesity in United Kingdom

3. Interventions of childhood obesity

4. Interventions of childhood obesity in the United Kingdom

5. Randomized controlled trials on childhood obesity interventions

Out of over 100 materials found, there was particular importance paid on materials which related to studies done in developed countries, particularly Western countries and China. Only materials which concerned policies in the United Kingdom and Western countries on childhood obesity were selected. One material concerning childhood obesity interventions in Australia and Indonesia was used. One study was selected from China on childhood obesity and only one study from developing countries was selected.

7.0 MULTI-FACETED INTERVENTIONS ON CHILDHOOD OBESITY

A randomized controlled trial was conducted in Jianye district, Nanjing China to measure the effect of a multi-faceted intervention to reduce CHO levels (Xu et al., 2015). The intervention program was school-based involving 8 schools randomly selected from 13 primary schools in Jianye. The authors of the study placed the first 4 schools in the multi-faceted intervention group (it entailed health education, parental training on diet and increased physical education) and the other 4 in the control group where they were given the normal health education. The study took one year after which BMI in comparison with the BMI taken before the start of the trial. The study had a positive outcome where schools involved in the multi-faceted intervention recorded greater reduction in BMI levels than in the control group. Whereas it is difficult to assess the accuracy of the data as other factors were not taken into consideration, it is evidence that multi-level intervention provides better results than a single approach intervention.

As there is evidence that both bad social and environmental factors play a role in creating high rate of CHO, it suffices that only a multi-level approach would reduce CHO rates (Perez-Escamilla et al., 2013). It has been widely suggested that the proper approach should include policy changes, health education and environmental changes.

The main components of a multi-level intervention are encouraging healthy diet and physical activity (Sassi, 2010).

A structurally effective programme must involve the local authorities on policing; take a school-based approach, family-based and community intervention (GLA Intelligence Unit, 2011).

Research shows that the reason for high rates of CHO is because the intervention mechanisms have not focused on changing policies by the authorities and creating conducive environment to discourage CHO (Olstad et al., 2016). Local authorities must promote healthy diets among its people by ensuring that advertisements are run on a nutrient-basis profile and create a policy to monitor changes in product ingredients and promote products that improve on the diet (HM Government, 2016).

An effective multi-faceted intervention ought to be school-based (Flynn et al., 2006). Evidence suggests that intervention programmes that allow schools to partake in their design and delivery are more effective (Waters et al., 2011). Programmes implemented in schools should undergo process evaluation and should be properly analysed to enable replication in other settings (Langford et al., 2015). For the approach to be effective, having physical activity classified as a core curricula activity would ensure that school administrations give it the seriousness it deserves (Perez-Escamilla et al., 2013). Staff development should be encouraged so as to build them as professional health educators and as mentors to children (Wind et al., 2008; Beetham and Sharpe, 2007).

A successful multi-faceted intervention must incorporate the family. A family-based approach is encouraged for a programme that entails pre-school children (GLA Intelligence Unit, 2011; Simon et al., 2006). Moreover, the ‘fat letter’ policy should be developed to provide further health education on the necessary action to be taken upon receiving the advisory (Royal Society for Public Health, 2015).

8.0 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

The aims and objectives of such a multi-faceted intervention must include several key factors for it to be considered successful (Xu et al., 2015).

Aims and objectives

1. Advertisement policy change

2. Reduced consumption of sweetened beverages

3. Ingredient changes on processed products

4. Increased physical activity

5. Change in BMI levels

6. Change in obesity-related behaviour

7. Reduced rate of CHO

8. Improved health education among underprivileged families

9.0 LOGICAL MODEL

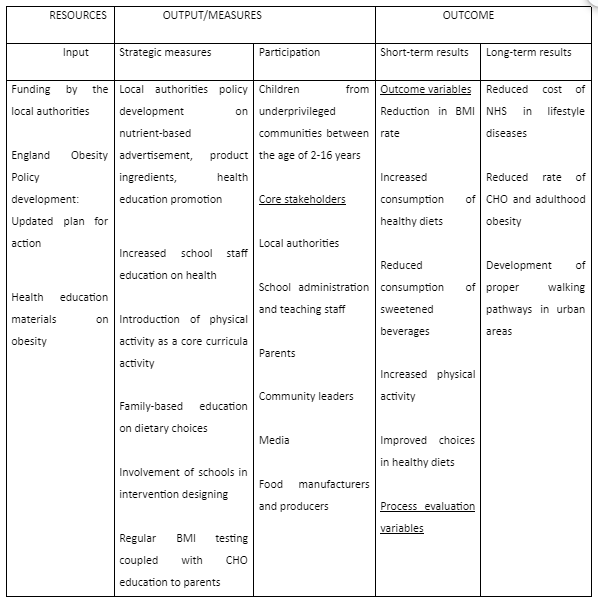

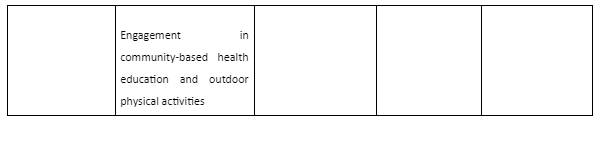

A logical model developed to ensure a seamless flow of functions and wholesome participation of all the relevant stakeholders can be used and illustrated diagrammatically. The model shows a casual flow of the inputs by each stakeholder and the desired measures needed at each level held by a stakeholder and the anticipated short and long term outcome.

Logical model of a multi-faceted intervention on childhood obesity in England

10.0 INTERVENTION DESIGN

1. Recruitment

The requisite stakeholders for the piloting of the intervention must be recruited from the marginalised members of a given community as CHO levels are high in underprivileged communities. Hence the pilot project would entail the local authority, schools, families and community-based institutions within these areas.

2. Intervention variables

The intervention should be contrasted on three key references or variable, namely; dietary changes, reduction in BMI and increased physical activity.

The dietary changes should reflect a move away from sugary foods as well as fast foods which are readily available in underserved localities (MRC Epidemiology Unit, 2018). Moreover, there should be evidence of increased sale of vegetables and fruits within the locality as they are associated with reduction in CHO (American Heart Association, 2014). Schools should also improve on menus and keep track on the choices that children make (Hamblin, Fellowes and Clements, 2017).

For the intervention to show effect, the health authorities will embark on BMI testing for all children keeping record of obese children. They should ensure intervention follow up on those already obese at the time of enrolling the intervention.

Increased physical activity will be measured by the change in school programming and quantitative survey of children walking to school.

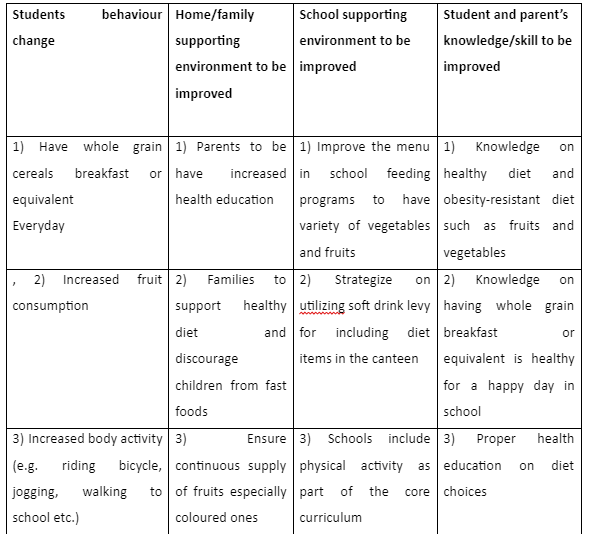

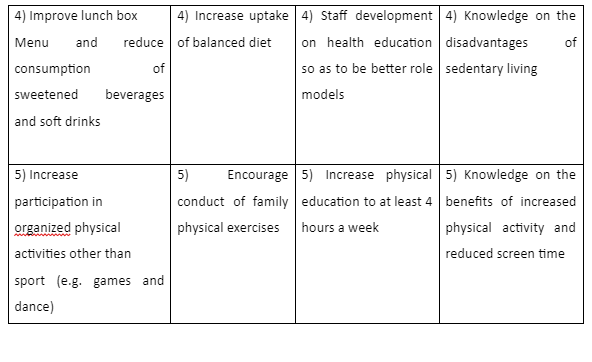

3. Outcome evaluation

This will entail collection of both quantitative and qualitative data upon completion of the pilot period. The ANGELO (Analysis Grid for Elements Linked to Obesity) methodology will be applied to analyse the effectiveness of the intervention program (Handayani et al., 2015). See the table below.

4. Process evaluation

The evaluation of the intervention programme requires the following key areas to be surveyed for the programme to be deemed successful.

Firstly, the trust of the intervention must be recorded across board especially by the parents and teaching staff. Low trust levels would mean that most of the recommendations given are never implemented. (Langford et al., 2015)

Secondly, the programme must be widely accepted by all stakeholders. Cases of lack of acceptability are mostly associated with intervention programmes that are culturally insensitive (Langford et al., 2015).

Thirdly, the survey must seek to know the barriers experienced by the stakeholders in the implementation of the intervention to ensure that further enrolment takes care of these concerns (Langford et al., 2015).

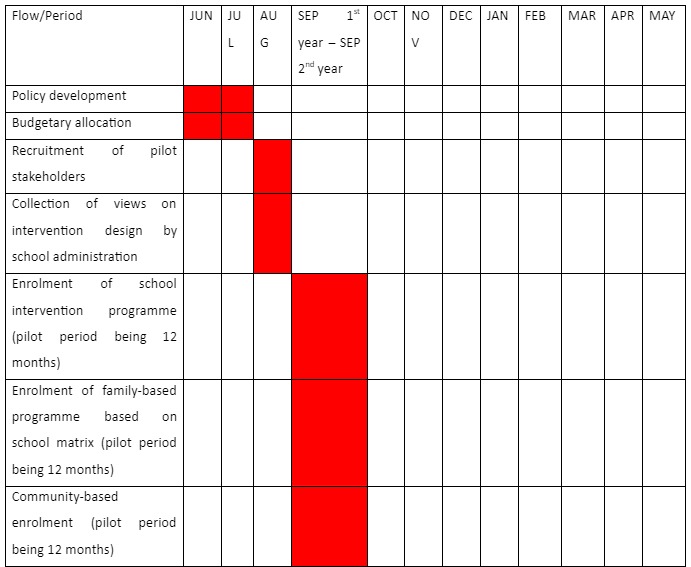

5. Action plan

The plan for action for the rolling out of the intervention would require a pilot period of one academic year, approximately twelve months. The programme would be initiated by the local health authorities in the underprivileged localities in conjunction with school administration. Trainings on health education would be conducted through the school and community institutions as this Gantt chart shows.

Gantt chart on the rolling out of a multi-faceted intervention programme

11.0 COST EFFECTIVENESS OF THE INTERVENTION

Whereas most studies done on the various models of intervention show the ultimate benefit in terms of the aims and objectives, they rarely show the immediate benefit in terms of cost implications (GLA Intelligence Unit, 2011).

Studies done by the OECD show that single-faceted interventions such as school-based approach are expensive but overtime are may be effective when spread over a long period of time (OECD, 2010). This intervention is cost effective as it encompasses non-medical activities thus resonating to the NICE analysis that ‘non-pharmacological’ interventions on diet and physical exercise are less costly during the period and as a long term effect (NICE, 2006).

12.0 ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES

The multi-faceted intervention is complimentary and proven to be effective as it encompasses all the spheres of a child’s life from home to school to playing to community activities. The programme is easily acceptable by the stakeholders as it allows them to own the process (Langford et al., 2015).

However, the intervention would have a problem with family engagement due to their economic status or just pure ignorance as other studies have also recorded the same (Eather et al., 2013). Furthermore, the process evaluation and outcome evaluation is subject to bias because of the quantitative methods of data collection especially from families.

13.0 CONCLUSION

Whereas CHO is a prevalent epidemic here in England, the last ten years have seen robust measures and interventions introduced to curb it capped with the action plan by the government introduced in 2016. However, these interventions have been segmental and have failed to touch every sphere of a child’s life. A multi-faceted approach comprising and starting with schools, local authorities, parents and community institutions has been studied to be the most effective as it encompasses the entire fabric of a child’s life. The intervention must however be based in schools as it is where most children spend the better part of their active life. In the long run the immediate cost of the intervention would be watered down by the decrease in treatment of lifestyle diseases in adulthood thus saving the NHS.

References

Beetham, H., Sharpe, R., ed., 2007. Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age: designing and delivering e-learning. Taylor & Francis e-Library

Brooks, F. et al., 2010. Health Behaviours in School-aged Children

Datar, A. and Sturm, R., 2006. Childhood overweight and elementary school outcomes. International Journal of Obesity, pp.1449–1460.

Deckelbaum, R.J., and Williams, C.L., 2001. Childhood obesity: The health issue. [pdf] Obesity Research, 9(S11), pp.239S-243S. Available at: doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.125.

Defra, 2014. Food Statistics Pocket Book: In Year Update. London:Defra

Eather, N., Morgan, P. and Lubans, D., 2013. Improving the fitness and physical activity levels of primary school children: results of the Fit-4-Fun randomized controlled trial. Prev Med, 56. Pp.12–9.

Flynn, M.A., McNeil, D.A., Maloff, B., Mutasingwa, D., Wu, M., Ford, C., 2006. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with 'best practice' recommendations. Obes Rev 7: pp.S7–S66.

Fox, M.K., Condon, E., Briefel, R.R., Reidy, K.C., and Deming, D.M., 2010. Food consumption patterns of young preschoolers: Are they starting off on the right path? Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(12), pp.S52-S59.

Gable, S., Britt-Rankin, J. and Krull, J.L., 2008. Ecological predictors and developmental outcomes of persistent childhood overweight. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture

GLA Intelligence Unit, 2011. Childhood Obesity in London. London: GLA Intelligence Unit

Hamblin, E., Fellowes, A. and Clements, K., 2017. Working together to reduce childhood obesity: Ideas and approaches involving the VCSE sector, education and local government. London: National Children’s Bureau.

Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2015. Health Survey for England 2014. [pdf] London: Health and Social Care Information Centre

Healthy Way to Grow Director, 2015. Policy Recommendations for Obesity Prevention in Early Care and Education Settings. American Heart Association and American Stroke Association

Kambondo, G. and Sartorius, B., 2018. Risk Factors for Obesity and Overfat among Primary School Children in Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(249)

Lobelo, F., de Quevedo, G.I., Holub, C.K., Nagle, B.J., Arredondo, E.M., Barquera, S., 2013. School-based programs aimed at the prevention and treatment of obesity: evidence-based interventions for youth in Latin America. J Sch Health, 83(9), pp.668-697

Noonan, R.J., Boddy, L.M., Knowles, Z.R. and Fairclough, S.J., 2016. Cross-sectional associations between high-deprivation home and neighbourhood environments, and health-related variables among Liverpool children. BMJ, [e-journal] 6; e008693 [CrossRef] [PubMed]

OECD. 2010. Obesity and the Economics of Prevention: Fit not Fat.

Olstad, D.L., Teychenne, M. and Minaker, L.M., 2016. Can policy ameliorate socioeconomic inequities in obesity and obesity-related behaviours? A systematic review of the impact of universal policies on adults and children. Obes. Rev, 17: pp.1198–1217. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Pan American Health Organization, 2015. Plan of Action for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents. Geneva: World Health Organization

Peña, M.M., Dixon, B., and Taveras, E.M., 2012. Are you talking to ME? The importance of ethnicity and culture in childhood obesity prevention and management. Childhood Obesity, 8(1), pp.23-27. Available at: doi: 10.1089/chi.2011.0109

Perez-Escamilla, R., Hospedales, J., Contreras, A. and Kac, G., 2013. Education for childhood obesity prevention across the life-course: workshop conclusions. [pdf] International Journal of Obesity Supplements, 3: pp.S18--S19 Available at: doi:10.1038/ijosup.2013.7

Prentice-Dunn, H., and Prentice-Dunn, S., 2012. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and childhood obesity: a review of cross-sectional studies. [pdf] Psychology, Health & Medicine, 17(3). pp. 255-273. Available at: doi:10.1080/13548506.2011.60880.

Public Health England, 2018. Child Health Profile; Public Health England. London: Public Health England

Sacher, P. M., Kolotourou, M., Chadwick, P. M., Cole, T. J., Lawson, M. S., Lucas, A., and Singhal, A., 2010. Randomized controlled trial of the MEND program: a family‐based community intervention for childhood obesity. Obesity, 18(S1), pp.S62-S68

Sheldon, K.M. and Elliot, A.J., 1999. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: the self-concordance model. J Pers Soc Psychol, 76: pp.482-497.

Simon, C., Wagner, A., Platat, C., Arveiler, D., Schweitzer, B., Schlienger, J.L., 2006. ICAPS: a multilevel program to improve physical activity in adolescents. Diabetes Metab, 32(1): pp.41–49.

Stamatakis, E., Wardle, J. and Cole, T.J., 2010. Childhood obesity and overweight prevalence trends in England: Evidence for growing socioeconomic disparities. Int. J. Obes, 34. pp.41–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition, 2015. Carbohydrates and Health. London: The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition

Wang, Y. and Lobstein, T., 2006. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Ped Obesity, 1, pp.11–25.

White, J., Rehkopf, D. and Mortensen, L.H., 2016. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in body mass index, underweight and obesity among English children, 2007–2008 to 2011–2012. PLoS ONE, 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Wind, M., Bjelland, M., Pérez-Rodrigo, C., Tevelde, S.J., Hildonen, C. and Bere, E, et al., 2008. Appreciation and implementation of a school-based intervention are associated with changes in fruit and vegetable intake in 10- to 13-year old schoolchildren - The Pro Children study. Health Educ Res, 23(6): pp.997–1007

World Health Organization, 1998. Health Promoting Schools: A healthy setting for living, learning, working. Geneva: World Health Organization

World Health Orgzaniation, 2012. Population-based approaches to childhood obesity prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization

Xu, F., Robert, S., Ware, Leslie, E., Tse, L.A., Wang, Z., Li, J. and Wang, Y., 2015. Effectiveness of a Randomized Controlled Lifestyle Intervention to Prevent Obesity among Chinese Primary School Students: Obesity Study PLoS ONE, 10(10): e0141421.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to Access To Healthcare Services.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts