Drivers of Loan Repayment in Microfinance

Chapter one: Introduction

Introduction

This study presents a quantitative research to answer the question: what drives loan repayment in European microfinance? Section 1.2 will provide a brief background of the research rationality, Section 1.3 will present the research’s aim and objectives, followed by section 1.4 that will provide an overview of the methodology which will be chosen for conducting the research and finally the structure of the dissertation will be presented in Section 1.5.

Background

For the past few years microfinance practices have become a much-preferred method for poverty alleviation. Poverty alleviation and creation of rural employment are the top priorities for any governments (Salehuddin, 2009). Based on the success of famous microfinance institutions (MFIs) in mobilising savings and distributing large amounts of credit, with high repayment rates and good outreach, microfinance induce enthusiasm among the donors, researchers, and even governments (Armendariz and Moruch, 2005). Yet, many challenges remain and need to be overcome to achieve the ambitious goals, attached to microfinance sector. One of these challenges is that many MFIs face sustainability challenges and it needs to demonstrate their ability to be financially sustainable that would allow them to work without any subsidies (Cozarenco, et al, 2013). The sustainability challenge in microfinance is crucial to sustain MFIs’ operations and prevent their potential mission drifts (Macchiavello, 2018). That causes the need to create new motivation models to overcome the low repayment rates and rises number of written off accounts especially in the developed countries (Pedrini et al., 2016). The study goal is to determine the factors that are affecting the repayment rate in personal microloans within MFIs in the developed countries (Scotland). By using secondary data from Scotcash’s database system, which is a not-for-profit organisation, formally operating as Community Interest Company based in Glasgow (CIC) (Glasgow City Council, 2018). Their main aim is to provide financial products and services to those who have difficulty in accessing the mainstream sources (Scotcash, 2018).

Aim and Objectives

Research aim

The aim of this research is to investigate the effects of borrowers and loan characteristics on to repayment performance to the Scotcash. This paper is intended to make a contribution to an improving the MFI’s repayment performance through a better exploration of its determinants. This would provide some guidelines to reduce the default probability by our research purpose are to conduct hypotheses from the literature review for different variables: borrower’s gender, age, household status, employment status and loan’s payment frequency.

Research objectives

Critically review the literature on factors that influence the repayment rate and conduct the hypotheses.

Develop the appropriate methodology.

Test and Identify.

The following section will provide an overview of the research methodology adopted for the dissertation.

Overview of the Research Methodology

The methodology followed the structure of the Honeycomb of research methodology (Wilson, 2014). A positivism paradigm was adopted for this research that is to achieve objective results by minimising the potential bias coming from interaction with research participants (Saunders et al., 2012). A deductive approach was adopted as the researcher works from the more general to the more specific. In this research, theory was extracted from literature, and then it was narrowed down into testable hypotheses (Wilson, 2014). The research adopted quantitative research, which is mainly associated with the numerical analysis and more to be objective and involve data collecting such as questionnaires. It attempts to analyse the determinants of loan repayment performance of Scotcash during 2018-19 (financial year) using numbers and statistics. This research is designed as a cross-sectional study of a full population of loans offered by Scotcash during 2018-19 (financial year). The research use secondary data were extracted from the Scotcash's database system "Metrics", which allows exporting data on loans granted for 2018-19 (financial year). This offered the opportunity to access the rich and good-quality data regarding the status of Scotcash’s loans and the borrowers’ characteristics. The research methodology is to conduct hypothesis through previous studies and apply different statistical approaches to test the strength and shape of association between borrowers’ characteristics (independent variables) and loan status (dependent variable). The independent variables are borrower’s 1) gender, 2) age, 3) household status, 4) employment status and 5) loan’s payment frequency. The hypotheses test results will be conducted by using Chi-square test of independence, Cramer’s V coefficient to define the coefficient level and the strength of the association and Correspondence Analysis (CA) technique to explore meaningful relationships between the latent (qualitative) components of both dependent and independent variable.

Structure of the Dissertation

This chapter provided the research’s rationale, identified research’s aim and objectives and provided an overview of the research’s methodology. The rest of the dissertation is structured as follows: Chapter Two: Critically review the literature on factors that influence repayment rate. It will go on to review different researches in the developed and developing countries. From this will conduct the research hypotheses. Chapter Three: Discuss and justify the methodology that was chosen to address the research aim and objectives. Chapter Four: Present and discuss the findings of the empirical research. Chapter Five: Conclude the dissertation and make recommendations to Scotcash in relation to the borrowers’ and loans’ characteristics that influence their repayment performance.

Chapter two: Literature Review

Introduction

This chapter will set out the literature review. It is divided into six sections. Section 1 introduces the context of the study. An overview of the microfinance and MFIs sector is firstly offered in section 2. Section 3 covers the sustainability challenges in microfinance sector. Section 4 describes the factors affecting loan repayment performance of MFIs. Section 5 demonstrates the study hypotheses. Section 6 concludes with the researchers’ gap.

Microfinance and MFIs

Irrespective of the massive number of financial institutions, the mainstream market excludes the deprived communities and a low-income individual from many financial services (Convergences, 2013). There are over 2.5 billion people around the world that cannot access the basic financial services due to different reasons such as high-risk loans and high operation cost without having any collateral. This exclusion has consequences on how poor and excluded people access credit: and leave them to “sub-prime” lenders such as payday and doorstep lenders, which offers high-interest rates on their loans due to high risk borrowers (Convergences, 2013; McHugh et al., 2019). One of the key practices that can play a critical role in minimising the gap and solve the market financial exclusion is microfinance. The microfinance practices make an alternative approach that reduces financial exclusion and giving access to financial services to households and low-income people in both urban and rural areas (Armendariz and Moruch, 2005). Therefore, microfinance acts as a tool, which alleviate poverty through the provision of alternatives financial products such as loans, saving, payments, money transfer, leasing contracts and insurance policies that are suitable and has been tailored to meet the needs for the poorest individuals, who have been excluded from the mainstream banks (Mota, et al, 2018; Ehrbeck, 2012). One of the main services of microfinance is microcredit, which is the act of offering small loans to business and personal purposes for needy people without collateral. Previously, the term microfinance had been considered exclusively offering loans to the poor. However, it is used as a broader term that includes any financial services for increasing the financial inclusions such as saving, money transfer, loans, and insurance as well as payment services. Therefore, terms such as microfinance and microcredit are often used as synonyms of offering small loans to needy individuals (Ledgerwood, 1999; Sengupta and Aubuchon, 2008; Ehrbeck, 2012). Moreover, microfinance institution (MFI) is defined as an organisation that offers microfinance services to low income individuals. Almost all MFIs offer small loans and many other in addition to that offer insurance, saving and other services. Also, they provide non-financial services as technical support such as training and capacity building program on self-confidence on financial and business management skills. There are different providers of microfinance services such as non-profit (often an NGO), Credit Unions (CUs), Microfinance Banks, Government Financial Services, Non-Bank Financial Institutions, a mutual fund or cooperative, a commercial company either banks or other companies such as non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and other (Massele, J., et al., 2015; BNP Paribas, 2016)

Over the past years, microfinance practices increased rapidly, and this had been stimulated by some of activities that are happened in the developing countries. For example, in the public recognition to Grameen Bank and ACCION International, Grameen Bank which was first launched in 1976 in Bangladesh by the Nobel Peace Prize winner and an economist, Muhammad Yunus was mainly meant to help in spreading the microfinance practices especially in the developing countries (Bhatt and Tang, 2002; Massele et al., 2015). After the financial crisis, which occurred between 2008 and 2010, the conventional loan system has been slowing down (Mota et al., 2018). On the other hand, Microfinance sector has been increasing its recognition, especially in the developed countries as an alternative to avoid the occurrence of other financial crises (Afonso, 2010). By 2017, microfinance services had reached about 139 million individuals, with a total of 114 billion dollars. This represents a 5.6% growth in total borrowers and a 15.6% increase in the total portfolio around the world (Convergences, 2018). Due to the success of microfinance in the financial sector, several types of research have covered numerous subjects and other areas that are related to microfinance industry in the developed countries (Hollis & Sweetman, 1998; Conlin, 1999; Gomez & Santor, 2001; Bhatt & Tang, 2002; Schreiner & Woller, 2003; Bateman, 2003; Hartarska, 2005; Calidoni & Fedele, 2009; Salt, 2010; Dale et al., 2012; Lenton & Mosley, 2012; McHugh, Gillespie, Loew, & Donaldson, 2014; Barinaga, 2014; McHugh et al., 2019). Still, there is the moodiest comparison to other studies conducted in the developing nations (Besley&Coate, 1995; Mosley & Hulme, 1998; Pitt &Khandker, 1998; Hollis & Sweetman, 1998; Woller, Dunford, & Woodworth, 1999; Armendáriz, 1999; Morduch, 2000; Armendáriz& Morduch, 2000; Wydick, 2001; Mosley, 2001; Anderson, Locker, & Nugent, 2002; Brau &Woller, 2004; Goldberg, 2005; Chowdury, 2005; Coleman, 2005; Gangopadhyay, Ghatak, & Lensink, 2005; Hermes &Lensink, 2007; Mosedale, 2005; Chari-Wagh, 2009; Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Chowdhury & Chowdhury, 2011; Maes& Reed,2012; Vaessen et al., 2014; Roodman& Morduch, 2014). In addition to that, microfinance sector in the developed countries is still missing the unified definition, but the European Commission tried to define it to contain all possible practices within the UK which are: a loan of up to € 25000 made to those unable to access mainstream credit or to new or existing microenterprises (Pedrini et al., 2016; European Commission, 2006). One of the microfinance services in the developed countries is the business microloans, which is a ‘small unsecured loan to individuals or group to start and expand businesses (Khavul, 2010, p. 57). Additionally, there are other products such as personal microloans which is a ‘small loan intended to assist the excluded persons from borrowing money for facilitating their social and economic integration’ (Carboni et al., 2010, p. 36). Usually, microfinance is related to loans to micro business and start-ups firms. On the other hand, personal microloans or social microloans are aimed at individuals facing some challenges due to unemployment or unexpected expenses (Pedrini et al., 2016).

Sustainability challenges in Microfinance Sector

While microcredit represents a new mechanism to alleviate poverty and decrease financial exclusion through fair interest rates and cost-effective lending, its real-world application through MFIs’ operations is not free from sustainability challenges, especially in the long run (Nawai et al., 2010). The sustainability challenge in microfinance is crucial because the sector has lastly shifted towards marketisation (Baklouti, 2013), with MFIs attempting to strike for both social and economic objectives. The marketisation of the sector has mainly occurred in developing countries where, despite policies aimed at improving the dual mission of microfinance, MFIs have not always proved able to balance their objectives (i.e. mission drift) (Macchiavello, 2018). Although of more recent inception, the sustainability paradigm has also entered more developed contexts (e.g. Europe), where favourable policies have been promoted by the European Union and some governments to sustain MFIs’ operations and prevent their potential mission drifts (Macchiavello, 2017). For example, McHugh et al. (2019) found out that, the majority of microcredit lenders in the United Kingdom perceive that government subsidies play a major role in protecting financial institutions from “mission drift”, despite adding complexity to MFIs’ operations. In developed countries, most microcredit institutions depend in fact on government subsidies and public fund to cover for their operational costs, and this cause for increasing the default loans rate and creating many sustainable challenges. Even though subsidies may represent an “incentive” for MFIs’ poor financial performance (McHugh et al. 2019), this appears through making borrowers to run away from the debts easily and therefore, causing high written off rates (Christen & et al, 2002). So, the borrowers appear less motivated to repay the loan and the lenders feeling less obligated to recover the loans. Another challenge is that, the subsidies can cause difficulty to other lenders that are not having government subsidies to make them self-sustainable. To overcome these challenges and be more dependents from any donations and grants, it is important to determine the factors causing the major proportion of defaults rates that affect their sustainability or at least the cash flow in hands. That’s why one of critical decision need to be addressed by the microcredits stakeholders is the trade-off between financial sustainability and social outreach (Mota, et al, 2018). Even group lending models work in some developing countries with very high repayment rate (Besley & Coate, 1995; Armendáriz, 1999; Sharma, and Zeller,1997; Wydick, 2001; Chowdury, 2005; Gangopadhyay, Ghatak, & Lensink, 2005) Inefficient use of group lending to share the risks is one of the challenges that MFIs face in the developed countries. This implies the work as a social sensation to increase the repayment rate (Bhatt and Tang, 1998; Calidoni and Fedele, 2009). The individualism oriented in the developed countries cause unwilling to corporate and share risks with other due to absence of social capital that make the group lending strategy ineffective (Bhatt and Tang, 1998). That causes the need to create new motivation models to overcome the low repayment rates and rises number of written off accounts in the developed countries (Pedrini et al., 2016).

The study of the determinants of microcredit repayment is crucial to decrease the repayment default and strengthen the sustainability of MFIs. However, the majority of studies conducted on this topic focus on developing countries, and mainly taking into account microloans for business purposes. As such, limited knowledge is available on the determinants of repayment rates in European microfinance. Furthermore, no research is available on microfinance for personal consumption, which is a common service offered by several European MFIs (EMN, 2018).

Factors Affecting Loan Repayment Performance of MFIs

Microfinance is an emerging sector that needs more investigation and research. The focus on repayment rate is still a rare subject (Despallier et al., 2011; Mota, et al, 2018), especially when it comes to empirical assessment of experiences of microfinance from developed contexts. Most empirical research has been in fact conducted in developing countries. For example, Idoge (2013) examined the repayment capacity of small farmers in South Nigeria. The results show that age, education level, loan size, and payment frequency have a positive influence on borrowers’ repayment capacity. Also, gender, marital status, household size, and the amount expended on hiring equipment have a negative influence on loan repayment capacity. Furthermore, Oke et al. (2007) conducted an empirical analysis of microcredit repayment in south western Nigeria. The study found that, improvement in income, increasing banking opportunities in the area, access to adequate business information, and joining cooperative societies would increase the rate of repayment. Finally, Umeh et al. (2018) examined the loan repayment among rice farmers in Enugu State. The study shows that, household size, farming experience educational level, and net farm income have a positive repayment effect. Addisu (2006) analysed the repayment rate of microfinance credit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Results of the study indicate that better repayment performance is strongly and directly associated with borrowers’ educational level and the cause for defaulted loans cause due to the attitude of borrowers towards the loan, as if it was granted, instead of a liability that needs to repay. Also, Abdul et al. (2014) found that, education level, payment frequency, age, and number of dependents have a significant effect on the repayment rate in Ethiopia.

In the case of Bangladesh, Godquin’s (2004), study offers a comprehensive analysis of the performance of MFIs in terms of repayment within the grouping methodology using survey covering 1,798 households. The study shows that loan size, age, duration of the loan, access to non-financial services, and group homogeneity in terms of age have a positive impact on repayment rates. Another study in Bangladesh (Sharma, and Zeller, 1997) found that, the group lending methodology is better than the individual ones, and loan amount affects negatively to repayment rates. In Ghana, According toWongnaa et al., (2013), education, experience, profit, age, supervision, and off-farm income have positive effects on loan repayment rate. Conversely, gender, and marriage have negative effects on loan repayment rate, while the effect of household size was found unclear. Similar results have been found for experiences of microfinance in Rwanda (Musafiri et al, 2009), Pakistan (Chaudhary et al, 2003), India (Mirpourian et al, 2015; Field et al, 2008), Malaysia (Roslan, et al, 2009; Norhaziah et al, 2012), Tunisia (Baklouti, 2013; Makorere, 2014, ), Latin America (Schreiner, 1999; Janda et al, 2014; Seijaset al, 2017), Yamen (Qasem et al, 2018) and Nicaragua (Mason, 2014). Only a few studies focused on developed countries. For example, Mota, et al, (2018) analysed the repayment rate for the National Association for the Right to Credit in Portugal. The study suggests that the main determinants of repayment rate in Portugal are nationality, education level, marital status and business activity sector. In other developed contexts such as United States (Bhatt et al., 2002), Canada (Alam, 2019) and UK Derban et al. (2005), scholars have only identified institutional factors that influence loan loss rates in Community Development Finance Institutions.

In order to conclude, literature in microfinance generally recognises that socio-economic characteristics of borrowers, as well as the ability of MFIs to dilute repayments can influence borrowers’ capacity to pay back their debts. In the next section, five hypotheses are developed through a closer analysis of relevant literature.

Hypotheses

From the literature, it will conduct hypotheses for five factors that may have significant influence on MFIs’ repayment performance. These factors were chosen because their significant affect within different literature as will demonstrate bellow. The second reason is because the easily accessible to different data that contain information which is needed to analyse these factors.

Gender

Generally, research has shown that, women are better payers than men (Hossain, 1988; Khandker et al., 1995; Sharma and Zeller, 1997; Gibbons and Kasim, 1991; Kevane and Wydick, 2001; Roslan et al., 2009), and for this reason some MFIs have been found to increase percentage of female borrowers as a strategy to increase repayment rate performances (Hulme and Mosley, 1996; World Bank, 2007; Armendariz and Morduch, 2005). However, most research supporting these conclusions is of anectodical nature (Cornwall et al., 2007). Despallier et al. (2011) conducted a quantitative study, which covered 350 MFIs from 70 countries over 11 years to test for gender effects on MFI repayment performance. They found a highly negative correlation between proportion of female clients and portfolio risk. This means that, the MFIs with a higher proportion of female clients carry significantly fewer provisions. In general, women are less risky borrowers. The gender factor also affects different MFIs depending on the legal and regulatory status and lending methodology. MFIs with more tailored products and aligned with the female needs have better repayment rates. In most cases, this was found relevant for NGOs, but not for big banks. For example, customised customers service with flexible payment frequency and different repayment modes (Mayoux, 2001; Johnson, 2004). The study suggested that, in order to increase the repayment rate, micro-financial institutions should focus more on women. As such, the following hypothesis is developed:

Hypothesis 1: Gender has an effect on an MFI’s loan repayment performance.

Age

Many scholars have suggested that, there is a significant association between age and repayment rate. For instance, some scholars found that younger borrowers are more associated to default because their habit to continue searching for new job opportunities. On the other hand, the older borrower more likely to repay the loan due to their experience and past extensive work within different field (Boyle et al. 1992; Reinke 1998; Özdemir 2004; Addisu 2006; Brehanu, et al, 2008; Roslan, et al, 2009; Abdul et al. 2014). Additionally, some scholars found that older borrowers are more associated to repay the loan due to their social and personal characteristics, appearing more self-aware and responsible. On the other hand, other researchers (Arminger et al. 1997; Dunn,et al, 1999; Brehanu et al, 2008; Oladeebo, et al, 2008; Roslan, et al, 2009) found that, older borrowers are riskier than the younger borrowers because of their characteristics. They can perform more technical and innovative functions, more determined, independent, and knowledgeable. In addition to that, some literature shows that the youngest (18-24) and oldest groups (60-plus) borrowers have the highest repayment rate, while the middle‐age (24-60) borrowers’ group would have the lowest repayment rate (Baklouti, 2013; Mota et al., 2018). As such:

Hypothesis 2: Age has an effect on a MFIs’ loan repayment performance.

Household Status

Some researchers found that married couples are less risky to default the repayment rate as compared to single borrowers due to more maturity and being more responsible (Carling et al., 1998; Vogelgesang, 2003; Baklouti, 2013). On the other hand, other researches considered that, the married couples would be riskier due to more financial obligations and expenses relatively with bigger family members than the single borrowers (Dinh et al., 2007; Wongnaa et al., 2013). As such:

Hypothesis 3: Household status of microfinance recipientshas an effect on an MFI’s loan repayment performance.

Employment Status

Employment status indicates whether borrowers have another paid occupation besides their business, which translates into an alternative source of income. Some scholars (Mashatola and Darroch 2003; Vogelgesang 2003; Ojiako and Ogbukwa 2012; Idoge 2013) found that another paid occupation tend to have a higher chance of repayment. Furthermore, alternative income in agricultural activities helps farmers repay loans even when harvests are poor (Brehanu and Fufa 2008; Wongnaa and Awunyo-Vitor 2013). As such:

Hypothesis 4: Employment status of microfinance recipientshas an effect on an MFI’s loan repayment performance.

Payment Frequency

Payment frequency is an important factor for MFIs’ loan repayment success, especially for among MFIs offering microloans for business purposes, which need suitable time to generate income in order to repay the loans. Payment frequency is also an important factor determining the success of personal microloans repayment. For example, Abdul et al. (2014) found that, there is a significant correlation between the repayment MFIs’ performance and the suitability of the loan payment frequency. As such:

Hypothesis 5: Payment frequency has an effect on an MFI’s loan repayment performance

The Researchers’ Gap

Although some literature covers the importance of loan repayment success in microfinance, most studies have focused on developing countries and microloans for business purposes. This literature review has found that a research gap exists when it comes to loan repayment performance of MFIs operating in developed contexts and through personal microloans. More specifically, personal microloans are widespread credit products in Europe that MFIs offer to tackle financial exclusion (EMN, 2018). As such, this dissertation aims to explore the factors that may affect MFIs’ loan repayment performance when microloans for personal consumption are offered in a developed context. This will be done by quantitatively explore the determinants of repayment success of an MFI operating in Europe (Scotland) and working mainly through microloans for personal consumption. The next chapter will cover the research methodology and data analysis technique to test the hypotheses.

Chapter Three: Methodology

Introduction

This chapter will set out the study methodology. The chapter is divided into five sections. Section 1 introduces the context of the study. An overview of the MFIs sector in the UK is firstly offered that is followed by a description of the case study: Scotcash. Section 2 covers the research philosophy and strategy. Section 3 describes the research design and data collection method. Section 4 deals with data analysis techniques. Section 5 concludes with ethical considerations and study limitations.

Empirical Setting

MFIs sector in the UK

Despite MFIs’ services mainly concentrate in Asia, Latin countries and Africa (Radermacher & Brinkmann, 2012). Still, around 7% (35 million) of European population is financially excluded; in the UK, 14 million people live in poverty (over one in five of the population) and 1.3 million of adults do not have a bank account (European Union, 2012). That is why; the growth of MFIs’ services appears with strong attention to increasing financial inclusion, defined as ensuring access to formal financial services at an affordable cost in a fair and transparent manner (Swamy, 2014). Combining the welfare system with the financial crises defines MFIs’ priorities such as: job creation, promotion of microenterprises, financial and social inclusion, and empowerment of specific target groups (Bendig, Unterberg & Sarpong, 2012). The main target group for the microfinance sector in the UK are people who are in the gray area of welfare which excluded from the welfare benefits that targeting the poorest such as the unemployment, the old and disable people, immigrant and low level of education and skills individual (Pedrini et al., 2016). Even, there is no unified definition of MFIs in the UK; still MFIs’ sector has received proper recognition and support from the welfare system to be an alternative solution to the mainstream financial exclusion. MFIs play critical role in supporting local economies across the UK by providing affordable credit to business and individuals. MFIs in the UK have been named as Community Development Finance Institutions (CDFIs), which are a diverse range of organisations that are unified by their commitment to providing financial products and services that are demand-driven, developed specifically for their customers (CDFA, 2014). There are around 50 CDFIs across the UK operation in four markets: business, social enterprise, personal and home improvement lending with a total of £254 million provided 52,120 loans in 2018 (Responsible Finance, 2018). In addition to that, the CDFIs provide support such as advice, training and mentoring alongside the loans. The result of this combined offer is an inclusive financial service that brings previously excluded and high-risk individuals and enterprises up to a level where they are creditworthy.

Scotcash

Scotcash is a Glasgow based not-for-profit organisation, formally operating as Community Interest Company (CIC) (Glasgow City Council, 2018). Founded in October 2006 and started trading in January 2007 with help from Glasgow City Council and GHA (Scotcash, 2019) and operates across Scotland and has branches in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Greenock. The main aim of the organisation is to provide financial products and services to those who have difficulty accessing mainstream sources. As a Community Development Finance Institution (CDFI) regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), Scotcash provides affordable credit with no compulsory savings, and it focuses on small, ethical and short-term loans. Their small ethical loans save customers on average £230 in interest charges. Scotcash is a one-stop financial inclusion service where clients can access a range of financial goods and services without the need to be sign-posted elsewhere (Scotcash, 2018). These include affordable loans, access to basic bank accounts and access to credit union savings accounts. Also, they provide access to a range of other related services, provided by their partners: energy advice to help reduce fuel bills, foodbank vouchers and high-quality money and debt advice. Since opening they provided 24,500 affordable small loans for £12.6m to low-income households, helped open 2,885 bank accounts, opened 928 savings accounts and have collectively saved citizens over £5.6 million in interest repayments had they taken the same loan with a doorstep lender (Scotcash, 2019). Scotcash differs from credit unions in that they offer affordable credit without the requirements to save regularly. They are also able to focus on the small sum, short term credit market and price for risk accordingly. On 2018, Scotcash won two awards at the prestigious Credit Awards 2018 in London: The Small Business Alternative Lender of the Year award and the Small Business Responsible Lender of the Year award (Scotcash, 2018).

Scotcash consider being the only MFIs that operates in Glasgow. Scotcash’s experience for over 11 years with their success and achievement allow them to expand their services outside Scotland to all over the UK. This expanding, which started on Mar 2018, brought new challenges that related to distance and default loan level. That is why the need to define the 7. Why should we look at repayment rate for Scotcash? 8. Restate your research question in the light of why we need to look at repayment rate for Scotcash.

Research Philosophy, Approach and Strategy

The research methodology consists of many approaches and strategies used to conduct the research (Wilson, 2014). It is crucial to choose the right methods to underpin the research and move in the right directions. In order to do that, we use the Honeycomb of research methodology (Appendix 1) as a reference to develop our research methodology. The Honeycomb of research methodology was chosen because it allows for the examination and exploration of each part of the research methods. These model is successful to address some issues that the other models fail to do (Wilson, 2014). The research philosophy is linked to the researcher view on the development of knowledge. The research philosophy is essential because it is the basis for how scholars approach research and clarify the research design (Wilson, 2014). The “research philosophy is related to questions of nature of knowledge, reality, and existence” (Collis and Hussey, 2014, p.43). When scholars believe that, an objective reality exists (i.e. independent from the researchers and research subject), then their research is usually underpinned by a positivist philosophy (Saunders, et al, 2009). This research is underpinned by a positivist philosophy. This entails that the main aim of this research is to achieve objective results by minimising the potential bias coming from interaction with research participants. Our research purpose is to conduct hypotheses from the literature review for different variables; gender (Hossain, 1988; Khandker et al., 1995; Sharma and Zeller, 1997; Gibbons and Kasim, 1991; Kevane and Wydick, 2001; Roslan et al., 2009, Despallier et al. 2011), age (Arminger et al. 1997; Dunn and Kim 1999; Baklouti, 2013; Abdul et al. 2014; Mota et al., 2018), household status (Carling et al., 1998; Vogelgesang, 2003; Dinh et al., 2007; Wongnaa et al., 2013; Baklouti, 2013), employment status (Mashatola and Darroch 2003; Vogelgesang 2003; Ojiako and Ogbukwa 2012; Idoge 2013; Brehanu and Fufa 2008; Wongnaa and Awunyo-Vitor 2013) and payment frequency (Abdul et al. 2014) and use statistical methods to test them, and that aligns with the positivism approach (Bryman, 2016). The research approaches can be defined to be deductive or inductive depends on the research. The inductive approach is starting with observations and seeking to establish generalisation about a specific phenomenon. On the other hand, the deductive approach tends to begin with known theories and try to test it. The deductive reasoning works from the more general to the more specific. Sometimes this is informally called a "top-down" approach (Wilson, 2014). In this research, theory was extracted from literature, and then it was narrowed down into testable hypotheses. In positivist and deductive research, hypotheses are then tested by means of observation (data) to confirm (or not) the original theories (Trochim, 2006). The research's purpose is to define the association between variables, so, collection of quantitative data and using of highly structured approach are some features of the deductive research (Wilson, 2014).

The deductive approach often aligns with quantitative type of research (Ghauri, et al, 2002). The distinguish between two common types of research strategies, quantitative and qualitative, is that the quantitative research is mainly associated with the numerical analysis and more to be objective and involve data collecting such as questionnaires while the qualitative is not and consider more to be subjective and involved data collection method as an interview. This research is quantitative in nature, and it attempts to analyse the determinants of loan repayment performance of Scotcash (financial year 2018-19) using numbers and statistics. In order to summarise, this research project is grounded in positivism philosophy and underpinned by deductive reasoning to analyse quantitative data and test hypotheses derived from theory (i.e. literature).

Research Design

The research design is the framework that guides the research process (Wilson, 2014). The research design can vary according to types of research, the research philosophy; approach and strategy influence the suitable type of research design. The research design is essential to define activities and time plan, research questions and sources and types of information needed to accomplish a research project (Blumberg, et al., 2011). This research is designed as a cross-sectional study of a full population of loans offered by Scotcash during 2018-19 (financial year). Cross-sectional studies aim to explore variation “in respect of borrower’s and loan’s characteristics through data collection on two or more variables, at one single point in time (Bryman, 2016). Once data are collected, quantitative cross-sectional studies aim to find patterns of association between two or more variables (Bryman, 2016).

Secondary data extraction: Scotcash’s loans (financial year 2018-19)

In the study, secondary data were extracted from the Scotcash's database system "Metrics", which allows exporting data on loans granted for a specified period. This offered the opportunity to access rich and good-quality data regarding the status of Scotcash’s loans and the borrowers’ characteristics (e.g. gender, employment status, age). The opportunity to access data on borrowers’ characteristics is not common in this type of research, especially if surveys are used to explore questions on sensitive topics such as loans in arrears or written-off. (Tinati, et al, 2014).

5,063 loans were extracted from April 2018 to 31st March 2019. Each loan is associated, in most cases, with only one customer, because each borrower is allowed to only have one loan at a time and 235 days is the average loan’s time. Thus, the likelihood to have repeated borrowers in the sample is quite low (see Tables 1 for the loans' number for 12 months). The secondary data was extracted from the system include the agreement number, loan’s status, borrower’s age, gender, household status, employment status, loan’s payment frequency and application entry point (online vs offline). There were many challenges during data extraction: first, the system represents the loans' status for a point-in-time snapshot when we pull the data from the system. For example, some loans appear as a "paid up" or "settled" on the system, but actually, they are "in arrears" during the loan's time with a new payment schedule. So, if the loan’s actual payment date after the schedule payment date that’s define as “in arrears” loan. In order to be accurate in the analysis the loan’s status column has been redefined and simplified as "paid up" which means loans in good status, "in arrears" which means loans has or had an overdue before and "written off" which means the written-off loans (see Appendix 2 for the new loan's status flowchart). In addition to that, there is some missing information such as the borrowers' age, the system only provides the borrowers' date of birth, and the age column has been created from the date of birth and the loan’s start date. Also, there is an enormous number of applications in the system that have been "declined" or still "in proposal" need to be excluded from the analysis. So, in order to clean and organise the data that we need in our study, different formulas and filters have been created in the "Metrics" system (see Appendix 3 for Metrics' formulas). The data has been imported into Excel to redefine variables to export them into the SPSS for Windows is the method for statistical analyses in this study (IBM SPSS 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

For the aims of this study, loan status is considered as dependent variable, with value "1" denoting "paid up" loan repayment, "2" stands for loans "in arrears" and "3" for "written off". Six potential factors affecting loan status were taken into account. These factors are: borrowers’ (1) gender, (2) age, (3) household status and (4) employment status; a loan's: 5) payment frequency and 6) application entry point (if applications were made online or offline). See (Tables 2) full explanation of variables.

Data Analysis Techniques

Analysis will be conducted by means of SPSS for Windows (IBM SPSS 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) data were imported directly from an excel spreadsheet. This study looks at bivariate relationships, testing for the existence of relationships, and attempting to describe the strength and nature of such relationships (Cohen, 1988; Leroux, 2009). All variables in the study are nominal (Table 3) and were firstly analysed using descriptive statistics. Descriptive statistics including charts, frequency table and percentages were used to provide an overview of data and explore hypothetical relationships between variables and between categories of variables. Association techniques including Chi-square test of independence and Cramer’s V test were used to test whether dependent and independent variables were significantly associated and whether these associations were of strong, medium or weak nature. The Chi-square test of independence (also known as the Pearson Chi-square test, or simply the Chi-square) is one of the most useful statistics for testing hypotheses when variables are expressed at nominal level (McHugh, 2013) The Chi-square is a significance statistic and should be followed with a strength statistic. The Cramer’s V is the most common strength test used to test nominal data when a significant Chi-square result has been obtained (McHugh, 2013). Chi-square value means nothing on its own and can be meaningfully interpreted only in relation to its association level of statistical significance (Bryman, 2016), which in this case is p < 0.05. That means that there is only 5 chance in 100 of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis. To identify if there is an association between the variables, a significance level below 0.05 (p value < 0.05) is required. Chi-square test depends not just on its magnitude but also on the number of categories of the two variables being analysed. This latter issue is governed by what is known as the “degrees of freedom (df)” (Bryman, 2016). It is important to examine both the correlation coefficient and the significance level, because the significant level will be affected by the size of the sample. Basically, the larger a sample, the more likely it is that a computed correlation coefficient will be found to be statistically significant (Bryman, 2016), since this study relies on a large sample, the p value may not be a reliable measure of significance. As such, it is important compute the level of strength, which is given by Cramer’s V. Cramer’s V coefficient, is used for the analysis of the relationship between two nominal variables. Cramer’s V is usually reported along with Chi-square test and not normally presented on its own (Bryman, 2016). If Cramer’s V is less than 0.1 the effect has a small size, if it is between 0.1 and 0.3 the effect has a medium size, and if Cramer’s V is above 0.5 the effect has a large size with degree of freedom (df) = 1 and the level of strength decrease when (df) increase see appendix 4 (Cohen, 1988; Kim, 2017). However, to give the coefficient it is recommended to square Cramer’s V. If the new vales are below 0.01 the effect has a small size, if it is between 0.01 and 0.1 the effect has a medium size, and if it is above 0.1 the effect has a large size (Pallant, 2007). For all hypothesis, if the Chi-square test is statistically significantly with medium to strong association which be presented by Cramer’s V, then the null hypothesis will be rejected, and conclude that there is a significant correlation between the loan’s status (dependent’s variable) and the factors (independent’s variables). While the Chi-square test is a very useful means of testing for a relationship, it suffers from several weaknesses. One difficulty with the test is that it does not indicate the nature of the relationship. From the Chi- square statistic itself, it is not possible to determine the extent to which one variable changes, as values of the other variable change. About the only way to do this is to closely examine the table in order to determine the pattern of the relationship between the two variables (Leroux, 2009). That is why Correspondence Analysis (CA) has been chosen to explore the relations among nominal variables with multiple categories (Hoffman & Franke, 1986).

Correspondence Analysis (CA) technique was further employed to explore meaningful relationships between the latent (qualitative) components of both dependent and independent variables (i.e. whether there is evidence of some proximity between dependent and independent variables’ categories that may explain better a bivariate relationship. CA visualizes the correspondence of multiple categories of variables in scatter plot projection. This can produce rich insights and help researchers answer questions such as: how do selected variables correspond with each other? To what extent? A key part of CA is the multi-dimensional map produced as part of the output. The correspondence map allows researchers to visualise the relationships among categories of variables spatially, on dimensional axes; in other words, it helps identify which categories are close to other categories on empirically derived axis. Each category becoming a point on a multidimensional graphical map, also called a biplot (Storti, 2010). Categories from each variable with comparable patterns of counts will have points that are close together on the biplot, which allowing for easier visualisation of the associations among variables (Storti, 2010). It is also important to note that most other exploratory statistical techniques do not provide a plot of associations among variables. CA focuses mainly on how variables correspond to one another and not whether there is a significant difference between these variables. Exploring categories of variables may help disentangle where the organisation may work more to limit write-offs and which categories of borrowers assist better. This can be important to prevent mission drift as well as contribute to the sustainability of the organisation. It is important to mention that direction of relationship is not statistically assessed by qualitatively appraised through descriptive statistics and CA.

Ethical consideration and limitation

The research does not always involve collection of data from participants. For this research, data were collected through a routine management information system. This was optimal in terms of time and resources constraints typically associated with postgraduate research projects. However, there are certain ethical issues concerning secondary data analysis, which should be taken care of. One of these issues is a potential harm to individual subjects and issue of return for consent. If the data contain identifying information or any information that could be linked to identify the participants, then must indicate how participants' privacy and the confidentiality of the data will be protected (Szabo, Strang, 1997). For this issue, Scotcash data have no identifying information and appropriately coded with the loan's number so that nobody can have access to individuals' identifying and sensitive information. Other issues with secondary data analysis are when data are not freely available for public use (Bryman, 2016). Although Scotcash operates as Community Interest Company (CIC), data on loans need permission to be accessed by individuals external to the organisation. As such, written permission for the use of the data was obtained from Scotcash and it is included in Appendix 5. According to Saunders et al. (2009), research methodology serves as the backbone of a research study. Quantitative research's primary purpose is the quantification of the data. It allows generalisation of the results by measuring the views and responses of the sampled population. Every research methodology consists of two broad phases, planning and execution. Therefore, it is evident that, within these two phases, it is likely to have limitations which are beyond researchers’ control (Simon 2011). This study comes with its own. First, although data from Scotcash are of good quality, it was impossible to distinguish between the "in arrears" levels (i.e. where one in-arrear loan was more severe than another). For example, if one loan was one day overdue and another loan more than 120 day in arrear, the same-level status of “In arrear” was assigned to both loans. This may affect the accuracy of in arrears weight and the impact on financial sustainably and cash flow. Even though, the purpose of the study is to find the correlation between two variables regardless of their levels. So, it has a limited effect on the study and the hypothesis testing methodology. Another limitation in the study is that the written-off loans do not reflect the actual numbers of write-offs. The written-off loans usually need, on average, around 180 days to be written off. Data were extracted 90 days after the financial year (2018-19) and met the lead time needed to be written off represent around 81% of the total loans’ number (see Table 1). The final limitation is that a small part of the sample of loans can be associated with repeated customers, and thus with repeated socio-demographic characteristics (i.e. some loans may have repeated observations for the independent variables considered in this study). So, if there is a customer with two loans which are considered as two separated loans. That’s may affect with one of Chi-square’s assumption that each subject (borrowers) may contribute data to one and only one cell in the χ2. If, for example, the same subjects are tested over time such that the comparisons are of the same subjects at different Times, and then χ2 may not be used (McHugh, 2013). However, the average loan's time is around 235 days, which makes unlikely the chances to have repeated customers’ characteristics association with population of loans for the same financial year.

Chapter Four: Findings and Discussion

Introduction

This chapter will test the hypotheses stated in Chapter 2 through the methods and data introduced in Chapter 3. More specifically, findings from this chapter will test:

H1: Gender has an effect on an MFI’s loan repayment performance.

H2: Age has an effect on an MFIs’ loan repayment performance

H3: Household status of microfinance recipients has an effect on an MFI’s loan repayment performance

H4: Employment status of microfinance recipients has an effect on an MFI’s loan repayment performance

H5: Payment frequency has an effect on an MFI’s loan repayment performance

This chapter is divided into two main sections. The first section presents descriptive statistics for each variable of interest (i.e. frequency, percentages and cumulative percentages). This section offers an overall analysis of the associations between outcome variables and independent variables’ categories (e.g. LIST HERE). The second section of the chapter includes inferential analysis to test the above-stated hypotheses by means of Chi-square test of independence, Cramer’s V coefficient and Correspondence Analysis (CA) technique. This analysis was conducted using SPSS for Windows (IBM SPSS 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Descriptive Statistics

From Chapter 2 each loan is the unit of analysis and that the study has 5,063 observations for the dependent variables, as well as the independent ones. Table 4.1 shows that there are no missing data in the analysis. Table 4.2 and Figure 4.1 show loan frequency for each loan status category. Among 5,063 loans disbursed between April 2018 and March 2019, 2,900 (57.4% of the total) were repaid on time (i.e. “Paid up”), 1,799 (35.5% of the total) were not paid on time (i.e. “In Arrears”) and 360 (7.1% of the total) were loan defaults (i.e. “Written off”).These figures may corroborate the literature in Chapter Twoas some authors (Bhatt and Tang, 1998; Calidoni and Fedele, 2009; Nawai et al., 2010; Baklouti, 2013; Pedrini et al., 2016; McHugh et al. 2019) argue that MFIs facing sustainability challenges especially in the developed countries. The need to create new motivation models to overcome the low repayment rates and rises number of written off loans. Which this may represent a threat for MFIs’ sustainability aims as well as a reason to target better-off clients (i.e. mission drift). In the next subsections, it will present the descriptive statistics for each variable and overall analysis of the associations between dependent and independent variables’ categories.

Gender

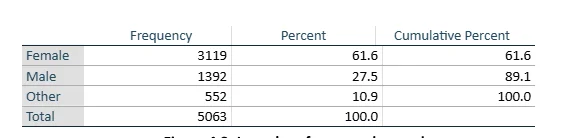

Table 4.3 shows that the female borrowers represent 61.6% of the total loans (n=3,119 loans) for the financial year 2018-19. On the other hand, male borrowers represent 27.5% with 1,392 loans and other category, which did not prefer to show their gender only represent 10.5% with 525 loans. Figure 4.2 shows that, female borrowers consists of 55.63% of the total as rapid loans (i.e.“Paid up”), 36.9% of the total as “In arrears” and 7.47% of the total as “Written off”. Although, the male borrowers suggest being riskier than female borrowers with 51.08% of the total as “Paid up”, 39.94% of the total as “In arrears” and 8.98% of the total as “Written off” loans. However, the borrowers define as “Other” substantially better than female and male borrowers with 82.97%, 16.67% and 0.36% of the total as “Paid up”, “In arrears” and “Written off “loans respectively.

Age

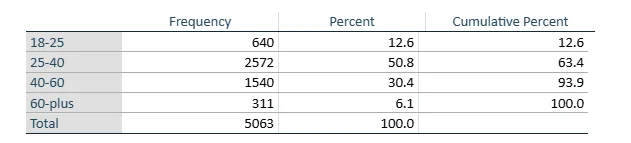

Table 4.4 shows that borrowers aged 25-40 represent the most borrowers 2,572 (50.8% of the total) followed by borrowers aged 40-60 represent1, 540 (30.4% of the total) after that aged 18-25represent 640 (12.6% of the total) and finally aged 60-plus represent only311 (6.1% of the total). There is a significant difference between number of borrowers age 18-25 and 60-plus with only (640) and (311) loans and the majority came from the age between 25-60, with (81.2%) the total loans. Figure 4.3 illustrates that successful loans (i.e. “Paid Up”) may be positively associated with borrowers’ age. This means that as age increases (i.e. borrowers are older), the proportion of successful loans increases. For example, paid up loans only represent 48.28% of the total of loans disbursed to people aged 18-25, 50.89% of the total to people aged 25-39, 66.17% of the total to people aged 40-60 and 85.85% of the total to people aged 60-plus. Even so the 60-plus borrowers only represent 6.1% of the total loans with limited effects to the total repayment rate. However, borrowers aged18-24 and 25-39 represent 63.4% of the total with higher proportion of riskier loans (i.e. “In arrears” and “Written Off) 50.4%in total with high effect to Scotcash’s repayment performance.

Household Status

Table 4.5 illustrates the frequency of loans by household status of the borrowers. As shown in the table, the lone parents with children represent 41.9% (n=2,123) of the total loans, followed by single adult borrowers (39.3%; n=1,989 loans), couples with children (13.5%; n=684 loans) and finally couples with no children (5.3% of the total loans). Figure 4.4 shows couples with no children have higher proportion of success loans (61.42%) compared to the other categories. Conversely, couples with children have the highest proportion of loans in arrear and written-off compared to the other categories of borrowers (38.89% and 8.77%, respectively).

Employment Status

Table 4.6 illustrates the frequency of loans by employment status of the borrowers. As shown in the table, the unemployed represent 45.6% (n=2,307) of the total loans, followed by full time (23.6%; n=1,195 loans), part time (11.8%; n=595 loans) and finally self-employed (0.8% of the total loans). Figure 4.5 illustrates the frequency of loan status according to categories of employment status. As shown, unemployed have higher proportion of success loans (60.73%) compared to the other categories. Conversely, self-employed, full time and employed have the highest proportion of loans in arrear and written-off compared to the other categories of borrowers.

Payment Frequency

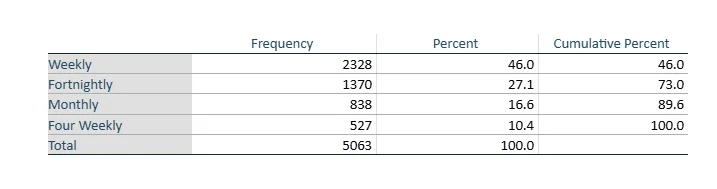

Table 4.7 illustrates the frequency of loans by payment frequency of the loans. As shown in the table, the weakly payment loans represent 46% (n=2,328) of the total loans, followed by fortnightly (27.1%; n=1,370 loans), monthly (16.6%; n=838 loans) and finally four weekly (10.4% of the total loans).Figure 4.5 illustrates the frequency of loan status according to categories of payment frequency. As shown, four weekly and fortnightly have higher proportion of success loans (64.71% and 62.34% respectively) compared to the other categories. Conversely, monthly loans have the highest proportion of loans in arrear and written-off compared to the other categories of borrowers (45.94% and 9.79% respectively).

Summary of descriptive statistics, most loans were disbursed to female borrowers (61.6% of the total loans), to people aged 25-40 (50.8% of the total), to lone parent with children and single adults (81.0% of the total), to unemployed and full time borrowers (69.2% of the total) and weekly and fortnightly payment frequency (73% of the total).

Inferential Statistics

The effects (significance and strength) of borrowers’ characteristics on loan status were assessed through Chi-square test for independence and Cramer’s V. Moreover, the association between categorical components of both dependent and independent variables were explored through Correspondence Analysis (CA). This analysis proved useful to better understand whether significant relationships between dependent and independent variables were driven by specific latent relationships

The effects of gender on loan repayment

The statistics results for gender shown in table 4.8, founds significant relationship (X2= (4, N=5063) = 181.659, p=0.00) with medium effect (Cramer’s V. =0.134 (Cramer’s V2=0.018)) between loan status and gender. Table 4.8 indicates that the sample size requirement for the Chi-square test of independence is satisfied (0 cells have expected count less than 5 and the minimum expected count is 39.25). This association has a medium effect as illustrated by Cramer’s V, and highly significant as indicated by Chi square statistic. The results prove statistically significant at a confidence level of 95 % (5%> p=0.000). So, the null hypothesis can be rejected in support of the hypothesis that gender of borrowers can have a medium-strength effect on their payment performance (H1),that being female has an influence on loans’ repayment performance. Table 4.8 shows that Inertia, which gives the total variance explained by each dimension, represents 3.6% of the total. This indicates that knowing something about gender explains around 3.6% of something about loan status and vice versa. It illustrates that the dimension 2 has 0.000 from total inertia (0.36) which indicate the dimension 2 should excluded from the analysis in Figure 4.7.1 (CA’s symmetrical normalization). Figure 4.7.1illustrates that female borrowers are more proximal to good repayment rate, i.e. paid up loan, as compared to males’ borrowers, who seem to be more associated with worse-quality repayment and write-offs.

The effects of age on loan repayment

The statistics results for age shown in tables 4.8, founds a significant relationship (X2= (6, N=5063) = 229.895, p=0.00) with medium effect (Cramer’s V. =0.151 (Cramer’s V2=0.0228)) between loan status and age. Table 4.8 indicates that the sample size requirement for the Chi-square test of independence is satisfied (0 cells have expected count less than 5 and the minimum expected count is 22.11). The results prove statistically significant at a confidence level of 95% (5%> p=0.000). So, the null hypothesis can be rejected in support of the hypothesis that age of borrowers can have a medium-strength effect on the repayment performance (H2), that being older (i.e. over 60 years old) has an influence on loan’s repayment performance. Table 4.8 shows that the total Inertia is (.045) with (0.44) from dimension 1 and only (.002) from dimension 2. Dimension 2 explains only 0.2% of the total variance accounted and would therefore be dropped from further analysis in Figure 4.7.2 (CA’s symmetrical normalization). Figure 4.7.2 shows that the borrowers aged 18-25 and 25-39 seem to be more associated with worse quality repayment and written off loans. However, the aged 40-60 and 60-plus seem to be more proximal to good quality repayment loans (i.e. “Paid Up”).

The effects of household status on loan repayment

The statistics results for household status shown in tables 4.8, founds a significant relationship (X2= (6, N=5063) = 14.996, p=0.02) with weak effect (Cramer’s V. =0.038 (Cramer’s V2=0.0014)) between loan status and household status. Table 4.8 indicates that the sample size requirement for the Chi-square test of independence is satisfied (0 cells have expected count less than 5 and the minimum expected count is 18.98). The results prove statistically significant at a confidence level of 95% (5%>p=0.02). Even so, the null hypothesis can be accepted due to household status has weak strength effect on the repayment performance. This reject (H3), that being married (i.e., having children) has weak influence on loans’ repayment rate. Even the null hypothesis was accepted but still there is a weak affect between loans status and household status. From table 4.8, the inertia level is low (0.003) and support the Cramer’s V results. Also, it illustrates that dimension 2 has 0.000 from total inertia (0.36) which indicate the dimension 2 should excluded from Figure 4.7.3’s (CA’s symmetrical normalization) analysis. Figure 4.7.3 indicates couple with no children and single adult more associated with good repayment loans than couple with children and lone parents with children. The results show that household status with children tend to be more associated with risker loans (i.e. “In arrears” and “Written off”) in both couple and single parents.

The effects of employment status on loan repayment

The statistics results for employment status shown in tables 4.8, founds a significant relationship (X2= (4, N=5063) = 51.233, p=0.00) with weak effect (Cramer’s V. =0.071 (Cramer’s V2=0.005)) between loan status and employment status. The results prove statistically significant at a confidence level of 95% (5%>p=0.000). Even so, the null hypothesis can be accepted due to employment status has weak strength effect on the repayment performance. This rejects (H4) that may suggest that being couple has a weak influence on loans’ repayment rate. Even the null hypothesis was accepted but still there is a weak affect between loans status and household status. From table 4.8 (CA’s summary table for the relationship between employment status and loan status), the inertia level is low (0.01) and support the Cramer’s V results. Figure 4.7.4 (CA’s symmetrical normalization) shows that employed and full time borrowers are more proximal to high risk repayment loans (i.e. “In arrears” and “Written off”) than other categories. On the other hand, part time, unemployed borrowers tend to be more associated with good repayment rate (i.e. “Paid Up”).

The effects of payment frequency on loan repayment

The statistics results for payment frequency shown in tables 4.8, founds a significant relationship (X2= (6, N=5063) = 86.883, p=0.00) with medium effect (Cramer’s V. =0.093, Cramer’s V2=0.0086) between loan status and payment frequency. Table 4.8 indicates that the sample size requirement for the Chi-square test of independence is satisfied (0 cells have expected count less than 5 and the minimum expected count is 37.47). This association has a medium effect as illustrated by Cramer’s V, and highly significant as indicated by Chi square statistic. The results prove statistically significant at a confidence level of 95% (5%> p=0.000). So, the null hypothesis can be rejected in support of the hypothesis that payment frequency of loans can have a medium-strength effect on the repayment performance (H5) that being a monthly loan payment has an influence on loans’ repayment performance Table 4.8 shows that Inertia represents 1.7% of the total. It illustrates that the dimension 2 has 0.001 from total inertia (0.017) which indicates that dimension 2 should excluded from the analysis in Figure 4.7.5 (CA’s symmetrical normalization). Figure 4.7.5 illustrates that monthly payment are more associated with worse quality repayment and write-offs. On the other hand, fortnightly and four weekly payments, which seem to be more associated with good repayment rate i.e. paid up loan. Even monthly and four weekly payment frequency seem to be similar in time interval, but they have different association with the loan status categories.

Discussion

Figure 4.7.1 illustrates that female borrowers are more proximal to good repayment rate, i.e. paid up loan, compared to males’ borrowers, who seem to be more associated with worse-quality repayment and write-offs. This resonates with literature that suggests that female borrowers are better player than men (Hossain, 1988; Khandker et al., 1995; Sharma and Zeller, 1997; Gibbons and Kasim, 1991; Kevane and Wydick, 2001; Roslan et al., 2009; Despallier et al. 2011). Figure 4.7.2 shows that the borrowers aged 18-25 and 25-39 seem to be more associated with worse quality repayment and written off loans. However, the aged 40-60 and 60-plus seem to be more proximal to good quality repayment loans (i.e. “Paid Up”). These findings support previous studies (Boyle et al. 1992; Özdemir 2004; Addisu 2006; Roslan and Karim 2009; Abdul et al. 2014) that younger borrowers have a higher chance of defaulting than older borrowers as they are less riskier due to their social and personal characteristics, appearing more self-aware and responsible. Other researchers (Reinke 1998; Brehanu and Fufa 2008; Oladeebo and Oladeebo 2008), suggest that, older and younger borrowers are less riskyfrom other because of their business related characteristics such as older borrowers have wider and relevant work experience obtained in their previous jobs or businesses. On the other hand, younger are less likely to default because of their technical and innovative functions, more determined, independent, and knowledgeable to succeed in their business. However, these conclusions may not be applicable to the Scotcash which offers only personal microloans. Figure4.7.3 indicates couple with no children and single adult more associated with good repayment loans than couple with children and lone parents with children. The results show that household status with children tend to be more associated with riskier loans (i.e. “In arrears” and “Written off”) either couple or single parents. This result may not be consistent with some researchers’ findings (Carling et al., 1998; Jacobson, et al, 2003; Vogelgesang, 2003; Baklouti, 2013) that single borrowers tend to be less responsible than married ones and also may not totally support some researchers’ results (Dinh et al., 2007; Wongnaa et al., 2013), which demonstrate that married borrowers tend to repay loans faster. Figure () shows that couple borrowers intend to be the worst and the best repayment characteristics depending on if you have or not have children. Figure 4.7.4 shows that employed and full-time borrowers are more proximal to high risk repayment loans (i.e. “In arrears” and “Written off”) than other categories. On the other hand, part time, unemployed borrowers tend to be more associated with good repayment loan (i.e. “Paid Up”). The results not supporting many scholars (Mashatola and Darroch 2003; Vogelgesang 2003; Idoge 2013; Wongnaa and Awunyo-Vitor 2013) which found other income has a positive influence on borrowers’ repayment rate, as they are more easily able to repay their loan. Figure 4.7.5illustrates that monthly payment is more associated with worse quality repayment and write-offs. On the other hand, fortnightly and four weekly payments, which seem to be more associated with good repayment rate i.e. paid up loan. Even monthly and four weekly payment frequency seem to be similar in time interval, but they have different association with the loan status categories. One reason for that might be because the strong association between payment frequency and employment status (see table 4.9 and figure 4.8.1) show that monthly payment is associated with full time borrowers, which also seem to be both of them more proximal to worse quality repayment rate (see figures 4.7.4 and figure 4.7.5 ). In addition to that, table 4.9 and figure 4.8.2 show that male borrowers seem to have strong association with full time borrowers. Also, male borrowers seem to be associated with monthly payment frequency (see table 4.9 and figure 4.8.3).The results show that borrowers who are male, full time and with monthly payment frequency seem to have strong associations with each other and with high risk loan (i.e. “In arrears” and “Written off”).

On the other hand, table 4.9figure 4.9.1 shows that there is an association between borrowers aged 60-plus and four weekly payments, which both of them seem to be more associated with good repayment loan i.e. “Paid Up”. Furthermore, table 4.9 figure 4.9.2 shows that 60-plus aged borrowers seem to have a strong association with “Other” employment status, which may contain the anticipated and retired borrowers due to no other employment status categories include them. Which the borrowers anticipated or retired (“Other” category) may be eligible for different kind of benefits, which are usually paid every four week (indirect, 2019).Table 4.9 and figure 4.9.1 support that 60-plus borrowers has an association with four weekly payment. Also, table 4.9 and figure 4.9.3 shows that seem to be an association with significant and strong effect between four weekly payments and “Other” employment status category. The results conclude that the borrowers’ characteristics who are aged 60-plus, “Other” employment status (anticipated or retired) and has four weakly payment seem to be more associated with good repayment loan and also have a significant and strong association with each other.

Summary

Chi-square test (χ2) can be used to verify whether a relationship is significant between any two categorical variables (Bryman, 2016). Table 4.23 shows that gender (H1), age (H2), household status (H3), employment status (H4) and payment frequency (H5) has a statistically significant relationship with loan status, at a 5% significance level. However, the large sample size in the study that causing more likely to be statistically significant (Bryman, 2016).In addition to that, the strength of associations was illustrated by Cramer's V are shown in Table 4.23. Of the five explanatory variables, there have medium strength association with loan status: Gender, Age and payment frequency. Two have weak strength association: household status and employment status. That is why the research accepted hypothesis H1, H2 and H5 which borrower’s gender; age and loan’s payment frequency have effect on the repayment performance. On the other hand, the study rejected hypothesis H3 and H4 which the borrower’s household status and employment status have no effect on the repayment performance (see Table 4.23).

Chapter five: Conclusion and Recommendations

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to conclude the research that was carried out to determine if the aim and objectives were successfully met. The aim of the research was to determine the factors that are affecting the repayment rate in personal microloans within microcredit institutions in the developed countries. This chapter is structured as follows: Section 5.2 will demonstrate research’s objectives. Section 5.3 will provide recommendations. Section 5.4 will discuss the strengths and limitations of the research and Section 5.5 will discuss avenues for further research.

Conclusions from the research objectives

Microfinance practices, which can play a critical role in minimising the gap and solving the market financial exclusion, which is caused by the mainstream market excludes the deprived communities and a low-income individual from many financial services (Convergences, 2013). That’s leave them to “sub-prime” lenders such as payday and doorstep lenders, which offers high-interest rates on their loans due to high risk borrowers (Convergences, 2013; McHugh et al., 2019). Still MFIs’ operations are not free from sustainability challenges, especially in the long run (Nawai et al., 2010; Baklouti, 2013). The sustainability challenge in microfinance is crucial to sustain MFIs’ operations and prevent their potential mission drifts. That causes the need to create new motivation models to overcome the low repayment rates and rises number of written off accounts in the developed countries (Pedrini et al., 2016). The study goal is to determine the factors that are affecting the repayment rate in personal microloans within MFIs in the developed countries to increase the repayment performance. The research methodology was to conduct hypothesis through previous studies and do different statistical approaches to test the association between borrowers’ characteristics and repayment performance and to define the strength and shape of the associations. The dependent variables were the borrower’s 1) gender, 2) age, 3) household status, 4) employment status and 5) loan’s payment frequency and the independent variables which was the loan’s status. The hypotheses test results were conducted using Chi-square test of independence and Cramer’s V coefficient to define the coefficient level and the strength of the association. The study shows that gender, age characteristics of the borrowers and loan’s payment frequency have an influence on the MFI’s repayment performance. Therefore, the hypothesis (H1, H2 and H5) was accepted based on significant level of Chi-square test and the association’s strength from Cramer’s V’s result. Female borrowers tend to more associated with good repayment loan than male. Furthermore, older borrowers seem to be more proximal to good repayment loan than younger borrowers. Finally, the study shows that monthly payment loans are more associated with worse quality repayment and write-offs. On the other hand, fortnightly and four weekly payments, which seem to be more associated with good repayment rate i.e. paid up loan.

On the other hand, the study shows that household status and employment status characteristics of the borrowers have weak influence on the MFI’s repayment performance. Therefore, the hypothesis (H2 and H3) was rejected based on significant level of Chi-square test and the association’s strength from Cramer’s V’s result. Even so, the C A’s symmetrical normalization show that employed and full-time workers and borrowers with children are more proximal to high risk repayment loans (i.e. “In arrears” and “Written off”) than other categories.

Recommendations

The results from the results and discussion chapter show that the borrowers characteristics who are male, full time with monthly payment frequency seem to be more associated with high risk loans i.e. “In arrears” and “Written off”. Scotcash need to put extra measures to ensure the borrower’s ability to repay the loans such as credit history and bank statement checking. On the other hand, the results show that borrowers who are 60-plus, “Other” (anticipated and retired) employment status with four weekly payment frequencies seem to have a strong association with good quality payment loan i.e. “Paid up”. Scotcash need to target these characteristics to increase their outreach with high level of repayment performance. In addition to that, borrowers who are female, older, unemployed and without children have more associated with good quality repayment loan comparing to other categories.

Strength and Limitation

This section will discuss the strengths and limitations of the research. The strengths will be discussed followed by the limitations.

Strength

The first strength, the opportunity to access rich and good-quality data on borrowers’ characteristics which is not common in this type of research, especially if surveys are used to explore questions on sensitive topics such as loans in arrears or written-off (Tinati, R., et al, 2014). The study’s secondary data were extracted from the Scotcash's database system "Metrics" which contains the borrowers’ socio-demographic characteristics for all loans that have been approved during the financial year (2018-19). The second strength in the research was the ability to use different statistics techniques to identify and explain the association between the variables. The Chi-square is essential to test the significance level and should be followed with a strength statistic. The Cramer’s V is the most common strength test used to test the nominal data when a significant Chi-square result has been obtained (McHugh, 2013). Also, the Correspondence Analysis (CA) technique was used to explore the relations among multivariate categorical variables (Hoffman & Franke, 1986). It is the ability to extract the most important dimensions, allowing simplification of the data matrix to make further insights about the correspondence (de Leeuw, 2005).

Limitation

Chi-square test assumption that may not be satisfied: each subject may contribute data to one and only one cell in the χ2. There are repeated customers in the same financial year, and thus with repeated socio-demographic characteristics. This may impact on the chi-square test. Even it is unlikely the chances to have repeated customers due to the average loan's time (235 days), still the study will be more solid if the secondary data has also the number of repeated borrowers. This study has several limitations, but the most significant is related to the fact that the empirical evidence given in the literature review chapter focuses mainly on MFIs’ that in the developing countries and mainly taking into account microloans for business purposes, which makes it difficult to make direct comparisons with other research. Final limitation, this research was based on an individual lending institution.

Avenues for further research