African Cultural Entrepreneurs in the UK

Introduction

Chapter overview

The thesis sets out to explore the experiences of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs in the UK. The study aims to contribute to debates on cultural entrepreneurship by examining the lived experiences of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs in a Western social and cultural context.

This thesis employs a multi-theoretical approach to elucidate a wide range of themes emanating from the data analysis. This research is situated on the intersection of cultural and entrepreneurship theory. It broadly draws from entrepreneurship and ethnic entrepreneurship theories and makes a direct contribution to discussions on cultural entrepreneurship.

The central question of this thesis asks: what are the lived experiences of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs in Birmingham? What are the particular experiences of being an African and first-generation cultural worker? I further explore the question: how is the cultural practice of first-generation Africans situated in the urban cultural context? This introductory chapter comprise five sections, namely: background; statement of the problem; contributions and significance of research study; research constraints and thesis overview.

Background

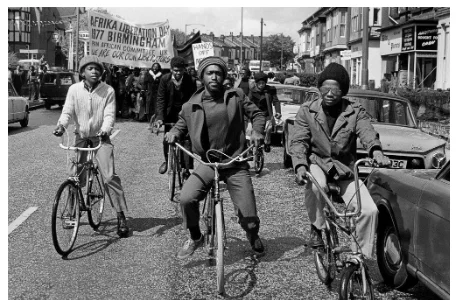

The reports and the images of Europe bound African migrants in the perilous Mediterranean seas have raised the profile of immigration debates mainly around the subject of cultural inclusion across Europe. This backdrop engenders discussions on modern 'societing' in the UK and in Western cities. Britain is becoming more diverse and characterised by a 'multi-colour' composition with a significant cultural, social, ethnic and religious variety (Benedictus, 2005). Across Europe, this socio-cultural diversity is demonstrated by estimates that reveal 9.9% of EU's population comprises people born elsewhere and two-thirds these come from outside Europe (Eurostat, 2016: 1). Apart from the statistics, this diversity is evidenced by the emergence of new landscapes across Europe's major cities, which act as the territorial containers in which the majority of recent migrants now live (Raco, 2016). Considering that a city often used as a testing ground for research and new urban policy strategies around living with difference (Phillimore 2013), the implication for European multicultural cities is cultural diversity and new arrangements of community life, which have raised issues of multiculturalism, inclusion, integration and cultural provision. The city of Birmingham has responded to its diversity by adopting a strategy of accommodation, which was demonstrated in 2015 by pledging to be a City of Sanctuary and a welcoming place of safety for all, proud to offer sanctuary to people fleeing violence and persecution (Birmingham City Council, 2019).

Most of Europe's major cities have turned to the promise of the cultural and creative industries as a response to the challenges of growing diversity. For instance, Oakley (2006) notes that the United Kingdom has linked the culture and creative industries with its diversity programs with the hope that the sector will provide employment to marginalised groups, to address the challenge of social diversity through access to work and of cultural inclusion and exclusion (Oakley, 2006). Accordingly, there has been increasing attention to the significance attached to the culture and creative industries for the economic development of cities and the emancipatory benefits to an individual. What is particularly appealing to policymakers is the promise that the culture and creative industries will address the old labour inequalities and open opportunities of employment for many regardless of race, class and sex (Florida, 2002). The belief in the merits of the sector have informed policy narratives which portray the culture and creative industries as open and meritocratic (Grodach, O'Connor and Gibson, 2017). While in the past culture was regarded as a merit good, now city planners see it as a resource for city development and development strategy itself (Ashworth and Kavaratzis, 2014). Many Western cities have imbibed the cultural-led urban development zeitgeist through the cultural quarter concept (Porter and Barber, 2007). Increasingly, studies have questioned the celebration of the egalitarian merits of the culture and creative industries by associating the sector with inequalities and precariousness. While the proponents of cultural work have highlighted the benefits of autonomy and creative fulfilment (Smith 1998; Howkins 2001; Florida 2002; DCMS 2001; Hartley 2005; Deuze, 2007) the pessimistic outlooks have outlined the intemperate working environments (Hesmondhalgh and Baker, 2011), measures of self-exploitation (McRobbie, 2011), discrimination based on gender (Gill, 2002) and the forced entrepreneurship-related aspects (Oakley, 2014). Thy study has corresponded to the capturing of actual experiences of entrepreneurship through culture through the empirical studies based information requisitions (Hesmondhalgh and Baker, 2011; Banks, 2006). By the study theme, the research has contributed to the discourses involving the cultural work based disciplines through the utilization of acquired experiences as a prism of perspectives and the first generation of the African Cultural entrepreneurs has been utilized to gain such experience from.Thus far, the studies of cultural work are dominated by the perspectives of indigene Europeans and multi-generational minority groups in the cities of the West. However, to this end, there are no studies that have considered the nature of culture and creative work through the experience of recently settled communities such as first-generation African immigrants. The previous census of 2011 had outlined that personnel of colored African origin has been gaining increasing significance and prominence in the UK. The national census report of 2011(Ons.gov.uk, 2012) the population of colored Africans has increased double folds from that of 0.8% during 2001 to that of 1.7% (from 484,783 to 989,628).

According to Eurostat (2018), immigrants from non-European countries accounted for 82 % of all who acquired citizenship of an EU Member State in 2017 and these were predominantly of African origin. The growing prominence of African settlement in the UK has seen the development of the African cultural industries. Among the many instances of African culture and creative industries in the UK is the Nollywood film industry, which has been able to record a continuous progression in the numbers of produced movies as per the quality and generation of revenues could be concerned (UK Nollywood Actors Guild, 2019). The growing prominence of African cultural industries in the UK is on its own a call for more scholarly attention to its nature and logic.

Statement of the problem

This thesis addresses the dominance of Western perspectives in cultural entrepreneurship studies literature. Alacovska and Gill (2019) contend that creative labour studies are virtually focused on the creative hubs from the Euro-American urban perspectives. Thus, the creative working personnel which they could comprehend are generally white in color, urban in nature, middle class and primarily are male. The arguments of Alacovska and Gill have suggested the necessity of questioning such notions regarding creative innovation which have been so far accepted universally as truths although such notions have been derived from the research processes which have been oriented towards the exclusive study of these supposed creative hubs from the Euro-American perspectives (Alacovska and Gill, 2019). Apart from these, the majority of the research studies on cultural entrepreneurship have retained their focus exclusively on the native population and more established ethnic groups, while neglecting recently settled communities. An observation of Birmingham's African community indicates significant cultural activities within the community. However, due to the recency of the first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs, most of the practice remains under the radar.

The cultural entrepreneurship of Africans in the UK has not been subjected to systematic research and remains unexplored. Most studies on the minority cultural practice have assumed a quantitative approach by concentrating on the levels of research engagement and have not involved qualitative exploration of the various experiences as well as the cultural customs of the individuals. In spite of the merit involving the quantitative research of participation levels by such individuals, the applied methods are mostly limited in terms of encapsulating the rich experiences of the participants concerning the discourse under consideration. The cultural entrepreneurship, in accordance with the entire perspective of African entrepreneurship within the UK, is primarily a tenuous undertaking. In spite of the expanding knowledge structure of the holistic perspective involving the ethnic entrepreneurship within the UK, entrepreneurship undertaken by the Africans have not been studied in depth. The dearth of studies in this perspective has persisted despite the fact that African entrepreneurs have superseded the Caribbean ones in number. So far, the performed studies regarding ethnic entrepreneurship within the UK (Ram and Jones, 2008; Lam, Harris and Yang, 2019; Smallbone et al., 2005) have primarily focused on the broadened categories of BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) communities. The studies performed have not been able to complete the gap in understanding of the specificities regarding the African cultural entrepreneurship effects. Nwankwo (2005) has outlined that the dearth of previously performed research focus regarding generic entrepreneurship of Afro-Caribbean personnel has culminated in the generalization of Black ethnic entrepreneurship as a singular and definite group. The application of vague identifiers such as the Afro-Caribbean entrepreneurship, African-Caribbean entrepreneurship, and Black entrepreneurship has consistently complicated and subsumed the entrepreneurship which has emerged from the African Black ethnic groups (Ojo, 2013). The paucity of appreciation of the uniqueness of the distinction of such entrepreneurial contexts that have been related to the minority groups has been further demonstrated through such indistinct designations.

Personal motivation and background

Part of the motivation behind this study is personal experience and reflections as a first-generation creative practitioner. I immigrated to the UK at the turn of the millennium. In the intervening period, I developed a multi-disciplinary cultural practice, which includes new media, journalism, photography and gospel music. I have released an album and had an experience with theatre production and directing. A significant part of my professional development was through higher education in the areas of media and communication. As a graduate and practitioner and creative professional my interactions with fellow minority creative professionals have prompted critical reflections on personal experience of working in the culture and creative industries.

Contributions and significance research study

A distinctive feature of the study is its interdisciplinarity approach and a web of conversations within a wide range of categories of theory. The thesis straddles the boundaries of cultural studies and entrepreneurship studies. I engage the discussions in the general study of entrepreneurship, while contributing to the discussions in the area of ethnic entrepreneurship. Although the study is primarily centred in the area of cultural entrepreneurship, the ethnic identity of the study population requires illumination from the debates in ethnic entrepreneurship to develop understanding about a specific entrepreneurial practice whose provenance is non-Western. The different experiences are explored through a variety of theoretical lenses which include spatial politics, Bourdieu’s theory of capitals, hopeful labour, liminality and double consciousness.

The significance and application of this study are both broad and narrow. The narrow focus is the context of the UK through the case of Birmingham. However, the findings of the study could apply in most European cities as the same questions could be asked about the experience of newly arrived cultural workers in a different context. The work provides qualitative knowledge of the experiences of the African cultural workers in the UK, which concurrently extends the knowledge of the qualitative experiences of minorities in the culture and creative industries, which so far has concentrated on the levels of participation e.g. Warwick Report (2015). The understanding of the experiences of first-generation Africans has potential significance for matters of integration into host communities in European policy. Correspondingly, the study contributes new knowledge of the spatial patterns of first-generation Africans, mainly how their cultural expression is hosted in the cultural infrastructure of the host cities and how it is evaluated in the processes of value assessment. The understanding of the spatial experiences of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs has implications for how new categories of cultural expression and practice are accommodated in Europe's urban cultural spaces.

The study contributes to the existing debates on the nature of culture and creative work (Gill and Pratt, 2008; Oakley's 2013; Forket, 2016 and Naudin, 2018). In these debates, I add the dimension of the constituency of recently settled immigrant group. The appreciation of the unique experiences of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs is achieved by contrasting and comparing with the knowledge of the nature of the native cultural entrepreneurship. The study adds to the existing debates on cultural labour by highlighting added dimensions of precariousness in the experience of new immigrant cultural entrepreneurs. I develop an understanding of a cultural practice that is deficient of host country capitals resources and the knowledge of the agentic capacity for navigating and mitigating the challenges.

The study instigates a departure from the broad BAME category towards a more particularised treatment of African cultural entrepreneurship. The understanding of African cultural entrepreneurship adds to the knowledge of the entrepreneurial actions of minority communities in European locales. This research could inform the actions of government policymakers whose remit may include immigrants and cultural inclusion.

A significant contribution is the understanding of the church as a significant space for the cultural entrepreneurship of first-generation Africans. The study explores the cultural economy of the church and the nature of its work and labour relations. The religiosity of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs raises important insights about how religious belief and tenets influence entrepreneurial intent.

The transnational dimension of the first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs affords understanding about the double-consciousness because of being variously located. The experiences of the being simultaneously attached to at least two cultural contexts raise insights about the transition experience to a new cultural context. The notion of liminality is employed to illustrate a major contribution of the study, which is the experience of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs of perpetual abeyance between existences. I contribute knowledge about the identarian schemes that arise from the complex experience of being variously located. The study uncovers the importance of a continentally rooted identity to African cultural entrepreneurship and how this is maintained through various performances.

Research constraints

The study deploys a collective approach to the research population. Although the intention was to depart from the monolithic treatment of African population in the UK, the same charge can be levelled against this study. This general approach overlooks the details of various cultural contexts in the African continent. However, the study is still significant for signalling a departure from the broad identifiers for Britain's ethnic minorities.

The final considerations are the limitations that pertain to the methodology and positionality of the researcher. Typically, the size of the sample in qualitative research often raises issues of generalisability. While some aspects of the research could apply to other contexts beyond the first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs, the data collection strategies and preferences may reduce the possibility of generalising this research to other contexts of Africans settlement. The qualitative nature of the data analysis and the researcher's shared experience with the participants can result in bias, which raises the importance of reflexivity and acknowledgement of the researcher as an instrument of data collection in qualitative studies.

Thesis overview

The thesis is constituted through eight different chapters. Chapter 2 consists of the literature review which is further subdivided into 3 parts. The first part has been the literature survey involving the cultural and creative industries and the cultural work-related aspects. To extend the credibility and authenticity of this academic endeavor, the exploration of the African creative and cultural industries has been undertaken alsong with the context of origin for the first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs. The second part entails a survey of the debates on the umbrella notion entrepreneurship and the subfields of ethnic entrepreneurship and culminating with a broader appreciation of the debates in cultural entrepreneurship. The third part considers scholarship on the significance of race and ethnicity in cultural production for the understanding of how these shape the lived experiences of new immigrant cultural entrepreneurs. The review exercise reveals the dominance of the Western perspectives on entrepreneurship and significant dearth in the studies of the cultural entrepreneurship of new immigrant communities. Chapter 3 has introduced the research methodology and design to outline the conceptual framework of the study. The rationale involving the Qualitative method of data collection and analysis would be discussed in the chapter as well and these discussions would involve semi-structured interviews through which the data would be collected which is augmented by participant observation and the urban walkabout. The chapter discusses the researcher's insider/outsider status and corresponding reflexivity on the potential influences and biases and the appropriate mitigation. I explain the practical steps and considerations for managing and analysing the data. The chapter will conclude by detailing the ethical considerations and approval for this research. An important consideration is the marginality of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs, hence the neeed for a methodological approach that affords the voice and sensitivity to their cultural idiosyncrasies.

The balance of the thesis is comprised of findings chapters. The presentation of findings took a thematic approach. Rather than have a chapter of specific findings then a chapter of discussion, the individual chapters combine the analysis, findings and discussion. The findings raise a wide gamut of themes, which are bound by a through-line of the experience of interstitial location and liminal existence in lived experience of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs. First, is the chapter 4 entitled as 'Birmingham as a place and space for African cultural entrepreneurship'. This chapter functions as an establishing shot of the geographic context of the entrepreneurial experience of the first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs. The aim of this chapter is to situate the cultural expression of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs in policy and geographical context of Birmingham. The focus on Birmingham is premised on the appreciation of the interactions, specificities and policies at local levels, and how their implication impacts its diverse residents. I explore the significance of Birmingham as a space and place for African cultural expression. The chapter is critical for characterising the African culture as interstitially situated which is a theme that is coupled with the aspect of liminality, which is pervasive throughout the study.

Chapter 5 is concerned with the experience of being a first-generation immigrant cultural entrepreneur. The objective of the chapter is to gain a profound understanding of the distinctive experiences associated with 'firstness' and recency of settlement in a foreign cultural milieu. The chapter considers how the first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs experience the process of resuming practice in a new cultural context. Pierre Bourdieu's theory of capitals is deployed for discussing the resources at their disposal, which are critical for effective practice in the native networks. The accounts of new immigrant African cultural entrepreneurs reveal invaluable insights into the experiences of embarking on a cultural enterprise as a first-generation immigrant. The chapter discusses the impotence of their human capital in the context of dense native networks. The findings are another instalment of rejoinders to the narratives of the openness of the culture and creative industries.

Chapter six is an in-depth exploration of the multiple dimensions of the centrality of the religion to African cultural entrepreneurship. The central argument here is that the theocentricity of African cultural workers is a significant distinguishing aspect for them from postmodern Western cultural entrepreneurship. The chapter explores the significance of the church for hosting the cultural practices of first-generation Africans and the tenets that influence the entrepreneurial ideologies regarding motivation and risk. The chapter contributes to procedures of debates on the spiritual dimension of cultural value in the experience of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs, which is often neglected by the fixation economic value. The discussions the religiosity is complemented the exploration of an aspect of transnationality in Chapter 7. The chapter is entitled "One foot here one foot in African" to portray the transnational dimension of the experience of the first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs. The transition from the African context to that of the cultural and creative sectors relating to the Western milieu is the focal point of this chapter. I explore the transition experience is a progression from one cultural logic to another. A broader discussion on the liminality aspect as a result of being held at a limbo between stations has been concentrated upon as well. The chapter explores how the first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs experience a perpetual tension of being simultaneously tethered to several cultural contexts and how the competing allegiances complicate and shape their sense of identity. Chapter 7 is followed by the thesis conclusion, which provides a summary of the findings. The chapter articulates the significance, implications and the major contribution to knowledge and reflects on limitations of this study and culminates with the suggestion for alternative lines of investigation.

Summary

The chapter has outlined the background and rationale for the study. It has also provided the significance and original contribution to knowledge, which have also involved the qualitative experiences of new immigrant cultural entrepreneurs. It also outlined the sequence of the chapters in the thesis. The outline of chapters mainly comprises the literature review, methodology and four findings chapters. The following chapter will be the literature view which is composed of three parts.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Preamble

A literature review is essential to perform an appraisal of the salient issues of current knowledge and to assess existent theoretical and methodological contributions to a specific research area. The goal of the review is to explore definitions and debates in the area of cultural entrepreneurship and its allied subtopics. The review road map begins with a discussion of debates on the subject of culture and creative industries in the UK. This will be complemented by an exploration of the scholarship on the culture and creative industries in Africa. The review process will proceed by examining the general entrepreneurship field and the key theories and models in the domain of ethnic entrepreneurship. At the centre of the review process is the notion of cultural entrepreneurship whose understanding will help to shape and clarify the contextual agenda for the rest of the study. The latter part of the literature review will focus on issues of race in cultural production.

Part One: Cultural and creative industries

Introduction

The previous two decades have outlined the formulation of a highlighted profile of the creative and cultural industries related policies and these have formed the backdrop on which the experiences of the first generation of entrepreneurs of African origin have been evaluated. The challenges which prevail in the global economy have been responsible to reinforce the necessity of alternative measures of production within the UK and Europe. Thus, the necessity of the development of new approaches regarding economic growth has been formulated as well. Such economic growth has not been established based on financial speculations. Instead, the emphasis has been on the adaptation to the climate changes, on the utilization of the IT applications in the most judicious manner, utilization of new applications from the nanotechnologies and biotechnologies and finally, implementation of institutional changes at the macro and micro levels(Neweconomics.org, 2017). The creative and cultural industries, apart from the responsibility of hosting the present research study undertakings, also effectively engage in the procedures of the first production and then in the distribution of the cultural texts. Thus, these have the potential to impart specific influences on the perceptual conceptions about the global scheme of operations (Hesmondhalgh, 2012). Specific understanding of the formulation processes of the texts could be gained through the cultural industries related studies and this approach could as well impart the understanding regarding the role of primacy accorded to such texts in the contemporary social structures (ibid). The ideological and symbolic charging of the outputs of the creative and cultural industries could be derived from the fundamental distinction which these industries have from those of the other industries. Thus particular social and political inquests are generated by such industries in opposition to the other conventional industries (UNESCO, 2013). The experiences related to the minority labor forces become imperative to be studied by the resultant appreciation of the significance of the ideologies associated with such cultural and creative industries. The assessment of the definitions of cultural industries would be performed along with the discussions of the semantic contextuality and fluidity of the same in the subsequent literature review section. This would involve a deliberate analysis of the various conceptions related to the ideas of the creative industries as a holistic policy initiative undertaken by the New Labour Government (Neweconomics.org, 2017).

Defining cultural industries and related terms

The exercise of defining the culture and creative industries presents a challenge of contextuality and interchangeability its terminology in different instances of scholarship and policy. The research will narrow the range of definitions to the European and UK context as the conception of "creative industries" varies widely according to geopolitical context and corresponding histories (Banks and O'Connor 2009, 366). Although the present work is essentially situated within the UK context, the African background of the focus study group has the potential to trigger further conceptual complexities as it will be discussed in the later sections. Most commentators cite 1997 when New Labour came into power and when the DCMS was established as the seminal moment when 'creativity' began to feature in policy and later in academic discourse (Moore, 2014).

Through the passage of the years, the discussions undertaken within this specific sector have been reflective of the new terms which have been generated so far and these involve "cultural and communication industries", "the creative business sector", "media industries", "content industries", "knowledge economies", "experience economy", "art-centric business" and"copyright industries"(Moore, 2014).

Kong (2014) has observed that within the previous two decades, the discourses of the creative industries have prevailed upon the policy-based and academic specifics and the outcome has replaced the previously observed references involving the cultural industries. Despite these, the terms such as “creative industries” and “cultural industries” could be often interchangeably utilized in various policy-based literatures which could reinforce the existing inconsistency of such terminologies and the associated confusion as well (Galloway and Dunlop, 2007). The subsequent review has been utilized to employ a bifurcated approach through treating the terminologies such as “creativity” and “culture” on an individual basis and to particularly reassociate the same with the existing industrial notions.

Hesmondhalgh (2007) has defined the cultural industries as the particular institutions which could be most significantly involved in the development of the underlying meanings. In this context, the cultural aspects have contributed to the generation of the debates which have been accorded greater significance based on the fact that such terms have particular nebulous nature. Throsby (2001) has outlined that the fundamentals related to the original implications of culture demonstrated activities that have further contributed to the artistic and intellectual developments related to any person. The concept had developed through the discourse of the time and the application of it had been undertaken to demonstrate the features including customs, social or demographic expressions as well as systems (Galloway and Dunlop, 2007). However, generation and communication of meaningfulness are essential concerning undertaking specific discussions about people (ibid).To this effect, O’Connor has defined the cultural industries as activities that are associated with symbolic goods the primary economic significance of which could be obtained from the cultural value (O'Connor 1999, p. 5).

According to Hesmondhalgh (2007), the debate does occur over the measure to which culture could be specified as a direct distinction of different cultural industries. Hesmondhalgh (2007) has suggested that it could be argued that all of the industries could be related to culture. Furthermore, he has also identified the possibility of the emergence of misdirection regarding differentiating the cultural industries from those of the other industries under the influence of the application of an extensively broader view.

In this context, considerable discussion has been generated by the conflation of creative disciplines. Creativity concept had been emphasized upon by the UK Labour Government as it outlined the creative industries as to have their origins in the formulation through the exploitation and generation of intellectual acumen (DCMS, 2001:5).

Hartley (2005) has defined creativity in the manner of the development of new ideas to identify the criteria, 4 in number, of such ideation. These are the necessities of creativity to be original, personal, useful and meaningful. However, these properties could become extensively problematic regarding the encountering of potential complications concerning the application in a certain creative workforce based operational contexts. As an instance, the personal element could become incongruous in terms of collaboration-based work processes within various creative and cultural industries. Hartley (2005) had outlined these two fundamentals regarding the creative industries to be affected by incompatibility. He has noted that creativity is suggestive of the preclusion of the entire organization on the industrial scale and the industries are indicative of the preclusion of majority of creative capabilities of the involved personnel from the process of consideration. Hartley (2005, p.106) has summed it up as creativity has got nothing to do with industries since it is considered to be a part of the human identity. The conception of this sector could be analyzed through the implications on it which could be further studied through the brief appraisal of the definitions directly associated with creative and cultural industries.

The definitional complexities in the study of cultural and creative industries have significance for scholarship and policy.

O’Connor (2010) has determined that such ambiguities associated with the classifications and definitional prospects have particular implications involving the mapping of the distribution and size-related dimensions of the sector through a statistical manner and this has been of conspicuous significance for the various groups of lobbyists and policy formulators as they are always in the requirement to demonstrate the economic significance of these and this outlines the worth of these in terms of becoming eligible to receive government intervention and assistance. Involving the instance of problematic infusion of the software elements in the definition of DCMS, it was necessary to be positioned within the sector as the future industry-based perspective (O'Connor, 2007). The statistical structural framework which is perpetually based on the outdated foundation of agro-industrial services substructures consistently contributes to the emergence of intrinsic difficulties in the identification of new professions and businesses and such complications have been frequently related to intrinsically. The process of distinguishing the sector and articulation of policy management required the application of both the numbers based approach as well as the utilization of actual conceptual work.

The UK and European definition and classifications of cultural and creative industries are the potential theoretical spot of bother for the present study. Considering the non-European background of the practice of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs, I envisage interesting definitional incompatibilities and potential issues pertaining to what is included and excluded as a cultural activity. The significance of these definitional schemes is their hegemonic potency in delineating different cultural activities according to the standards, aesthetics and taste of dominant groups.

The evolution of the term ‘cultural and creative industries’

The 'industry' element of the notion of culture and creative industries stems from the ancient history of commodity production (O'Connor, 2010). Whereas the conflation of culture and industry is associated with Theodor Adorno, who in 1947 collaborated with Max Horkheimer their piece 'The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception' (Adorno and Horkheimer, 1979). Although the coining of the term' culture industry' was a critique against the mass production of culture commodities, the term was later adopted as an identifier of the cultural sector. According to Kong (2014), Adorno criticised the culture industry for producing standardised cultural commodities to be commercially exploited by the elite. They identified film, music and magazines as some of the perpetrators of this standardisation, where culture impressed the same stamp on everything (Adorno and Horkheimer, 1979). Their main accusation was that culture industry lowers standards of appeal and sacrifice talent, individuality and creativity in the bid to appease public regulation and funders (Witkins, 2003). However, O'Connor (2010) notes that Adorno should not be equated with the conservative cultural opponents of 'mass society', instead, his criticism was aimed at the glittering novelty of popular culture, and 'high art' means of suppresses reflection and thought. Adorno also criticised the culture industry's treatment and transformation of the modern worker into an industrial machine (Adorno and Horkheimer, 1979). Notwithstanding the influence of Adorno and Horkheimer's criticism, they have also generated countercriticism. Hesmondhalgh (2007) contends that the negative conceptions harbored by Adorno and Horkheimer involving the culture industry did emanate from the human activity based artistic associations to which they had been privy to. Such an observation has been indicative of the attempt to reflect the conditions of life for the existing society to aspire towards the formulation of a utopian measure of living. Furthermore, the world has undergone a considerable transformation from the counterculture based sentiments of the 1960s and 1970s which had shaped the opinions of Adorno and Horkheimer.

Despite the early criticism, the culture industry started to gain recognition upon the realisation that it is also made up of not-for-profit and governmental organisations whose preoccupation was the production of social meaning (O'Connor, 2010). Thusly, from the 1960s onwards, culture industry was viewed less pessimistically. Notably, the perceived benefits are from technological and financial resources which capitalism is associated with (Hesmondhalgh, 2013, p.25). The mass production of culture was viewed as opportunity for democratisation of consumption and production (ibid). Hesmondhalgh also states that the culture industry discourse found its way into policy parlance in the form of the plural – cultural industries (Mommaas 2009, 51; O'Connor 2011, 38).

He has also outlined that the interconnectivity and complications of multifarious cultural production sectors have been acknowledged through the plurality form to determine the uniqueness of each of the particular fields. The policy-based transformations involving shifts from the cultural to creative industries were responsible for the impetus of similar transformation from cultural industries to cultural industries (Kong, 2014).

The UK government during 1997 had coined the term creative industries to classify the primary policy sector of it and to replace the previously utilized concept of cultural industries even though Australians had laid their claim to the term of creative industries (Howkins, 2002)

The cultural industries and creative industries are often perfunctorily passed as one concept and used interchangeably. However, there are a number of identifiers which suggest that creative industries as a clear policy and ideological break from the antecedent. According to Galloway & Dunlop (2007), the creative zeitgeist led to the jettisoning of the elitist and exclusive 'culture' in favour of 'creativity' which is viewed as inclusive and democratic. The distinction of the creative industries is the association with technology.

Cunningham (2001) has argued that the previously accepted concepts of cultural industries have been superseded by the development of the latest technologies such as extensive digitization and the Internet. He has also added that whereas the cultural industries considered as a classic had emerged from the technological progression undertaken during the early phases of the 20th Century, the creative industries had emerged through the technological changes which had occurred during the late 20th and early 21st Centuries. The argument has centered on the observation that the new measures of creative technological applications have ensured that the public has been liberated from their dependence on the outdated cultural industries such as the mass entertainment production processes undertaken by large corporate groups involving real-time based public consumption of the artistic creations (p. 25). Cunningham has outlined that the application of technology has been undertaken by small yet creative businesses in a measure that has been threatening the established models of businesses involving the large and dominant commercial organizations. This notion has been subscribed to by Uricchio as well (Cunningham 2001, p. 25; Uricchio 2004, p. 86–87). The creative industries era ushered a raft of key policy developments, which began with the inclusion of new categories of such as entertainment and leisure business not considered in the under the cultural industries dispensation (Kong, 2014). The developments were underlined by pragmatic political rearrangements such as the change from Department of National Heritage to Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) (O'Connor, 2010).

The statuses of cultural policies and associated industries have been renewed by this from a particular point of view. The events such as providing new names to these as creative industries and formulation of the 'Creative Industries Task Force' involved several significant players in the industries such as films, fashion, music and gaming disciplines who became participants to the euphoric enthusiasm as well as the political hubris which surrounded the concepts of Cool Britania and this was integral to the new labor government as well (O'Connor, 2010).

Also, the new terminology- creative industries – was a pragmatic move to enable the passing of key spending plans past the Treasury, which other would be difficult with "culture" and its association with non-economic arts (Cunningham, 2002; Redhead, 2004; Hesmondhalgh and Pratt, 2005; Selwood, 2006).

O'Connor (2010) observes that the turn to creative industries was partly inspired by ideas of technological 'information' and 'knowledge' economy. The creative dispensation came with the intention to exploit intellectual property (IP) as revealed in DCMS (1998:3) the definition related to the creative industries has outlined that creative industries have their origin in skills, innovation, talent, and creativity on the individual basis and these industries have also demonstrated their capacity to create employment and wealth through generating and then exploiting intellectual property effectively. Thus, creative industries have been earmarked for imperatives of commercial and economic nature.

Some scholars have steered clear from the notion of creative industries because of its ideological baggage and agenda, e.g. gentrification (O'Connor and Gu, 2012). The recent policy era saw the increased instrumental deployment of creative industries, among many other schemes – in the urban regeneration agenda. Gray (2007) states that, the instrumentalisation was part of a new political approach where the governments focused on the role of cultural and artistic resources as contributors to economic growth. These included other public initiatives such as remedying of social exclusion and community empowerment. Some have raised an issue about the indefiniteness of the term by arguing that all industries are creative. However, for the present study, the pursuit of definitional and conceptual finality has limited purchase to the study of what is, after all a non-Western oriented practice.

The study has adopted an inclusive approach through inculcating the terminologies associated with creative and cultural industries, even though the meaning of this term consequently varies extensively on a contextual basis. This has been the outcome of consistent variations in the evolutionary process of the meanings of these terms such as related to the classification of fashion shows, video games, and carnivals in the models of creative and cultural industries (UNESCO, 2013).

This juncture is crucial to highlight the various other debates such concepts as to be reflective of the Western thought processes. The primary and fundamental argument regarding such a study has been that the existent knowledge concerning the creative and cultural industries have been mostly formulated on an insular basis as these neglected the contemporary events related to patterns of migration. This lacuna would be addressed through considerations regarding the scholarships which have been formed on African creative and cultural industries associated topics in the subsequent discussions.

The culture and creative industries in Africa

Several authors have lamented the absence of African voices in the area culture and creative studies, which makes the review of African culture and creative industries a challenging exercise. The paucity of African perspectives is partly attributed to the preponderance of occident scholarship, which is marked by the exclusion of knowledge of industries beyond the 'Global North' (De Beukelaer, 2016). The same omission is observed in some seminal literal works which ostentatiously claim to focus on the 'global creative industries' (Flew, 2013; Hesmondhalgh and Saha, 2013). In contrast to the studies of Western culture and creative studies, it is not possible to conduct an in-depth appraisal of the literature on African cultural and creative industries because studies are extremely rare (UNESCO, 2013). The lack of data is complicated by the extensive heterogeneity perspectives and cultural practices across the continent. The heterogeneity is also attributable to the diversity of country-specific definitions and a vast cover range of cultural phenomena (UNESCO, 2013). Hence, it is not possible to render a full-fledged assessment of the present state of knowledge. Instead, this section offers an overview of key trends across the continent. However, it could also be a possibility that the confusion has been about the activities which constitute the African creative economy. Hence, the necessity remains that African cultural practices have to be accepted on meritorious grounds outside the existing nomenclatures (De Beukelaer, 2015). The fuzz in the conception of culture and creative industries is further complicated by the lack of systematicity in the study of the sector in the African context. The scholarships of African cultural and creative industries are not well-coordinated culture and not yet established as a subject. The lack of sustained scholarship is further impacted by the resistance to Western terminologies. According to De Beukelaer (2015), the African cultural practitioners are reluctant to fully embrace the established terms and a general lack of adherence to the idea that, creative industries could be identified with the production, dissemination and consumption procedures.

Mostly, the notion of 'cultural industries' is resisted on the basis that the continental sector not yet fully organised and does not conform to established models (De Beukelaer, 2015). The resistance to Western terminology is not surprising to the present study, as the discontent with the dominant perspectives is a cardinal idea in this study. The awareness of the discontentment contributes to the prominent argument of this study for an inclusive culture and creative scholarship beyond the confines of Western knowledge. I argue that Western concepts of cultural and creative industries are not universally applicable and advocate contextual sensitivity, particularly when approaching the African context with its vastness and variations in the cultural context. Pratt alludes to the rampant uncritical implementation of terminology and policies in international advocacy with insufficient consideration of cultural context (Pratt 2009). However, it is essential to acknowledge that some of the continuities exist between cultural contexts.

The acknowledgement of the vastness and diversity of cultural expressions across the African continent is essential for appreciating the complexity of achieving a collective commentary on its culture and creative economy. The understanding of different vernaculars across the continent has significance about what is considered as cultural and not. For example, considerable cultural activity in Africa is located in the church, marriage ceremonies and funerals. Kovács (2008) notes that the notion of creative industries by African institutions incorporates most of the fields and definitions used elsewhere, although they tend to include various format of expressions which have considerable significance involving the African cultural diversification, verbal traditions, performance-based arts, indigenous wisdom based particularities and the associated potentials of the tourism industry.Kovács has further highlighted that the creative industries related roles have been accorded with specific emphasis in the process of preservation and promotion of African identity as well as authenticity for the purpose of development of the entire continent. The subsequent sections will review works for an in-depth conception of African cultural economy.

The conception of the African culture and creative industries is founded on the general description of CCIs in the 'developing' countries. The scholarship on the African culture and creative industries is paradoxically predicated on two opposite views. Firstly, the acknowledgement that cultural and creative activity thrive abundantly in 'developing' countries (Throsby 2010,191). Second, that the existing practice is merely 'embryonic' or 'emerging' and best characterised as craft than industry (d'Almeida and Alleman 2010, 7). According to De Beukelaer (2016), Africa's contribution to the world's cultural and creative economy remains minuscule. However, African Business (2014) reports that the region is home to immense talent, although it lacks the capacity to exploit its creative talent and in order to benefit from its vast cultural fortunes. The same report states that Africa's portion of the global creative economy is a mere 1% and North African countries and South Africa as the main contributors. However, the stats represent a partial story as scholars have cited the pervasive informal nature of the cultural activities across the continent (Mbaye and Dinardi, 2018; Jedlowski, 2012; Lobato, 2010). According to Lobato (2010), informality defines the culture and creative industries in most developing countries, partly due to week regulation and lack of government subsidy. A plethora of studies explored the informality of African can culture and creative industries by citing the case of the Nigerian Nollywood film industry (Haynes, 2007; Jedlowski, 2012; Miller, 2016). The Nollywood has attracted the attention of scholarship for its decentralised distribution model and is now generating considerable revenues in spite of its mostly low budget productions. According to Lobato (2010), Nollywood succeeded in producing content that is relatable to African audiences and emerged as a powerful industry despite the absence of copyright regimes. However, most of the scholarships in the study of African cultural and creative industries fall under the themes of development and intellectual property.

Culture and creative economy as a development strategy

The development of the African creative and cultural industries has witnessed some of the most vociferous debates and these have mostly pertained to the holistic development prospects of the creative industries. Both the culture and creativity are perspectives that have the potential to enable certain disciplines since these are most human-centric development approaches (Flew, 2014). This approach has consistently emphasized on the particularity of the opportunities available to the developing countries to consider cultural policies as much greater than proper support for the performing arts and creative industries as well as for the cultural heritage protection and preservation purposes (ibid).

According to Flew (2014), the potential for the creation of employment, positive social contribution, self-reliance as opposed to dependency on a large measure of capital infusion and the ability to draw from the stocks of intangible cultural capitals related to values and identities of people have formulated the bedrock of appeal of the creative and cultural industries. Apart from these, the swift decline in the production and distribution costs associated with the global expansion of digital media networks related technologies have consistently further enhanced the possibilities through enhancement of the accessibility of new market horizons involving various practices and products related to culture(Kulesz, 2016). This particular instrumentalization of culture has been in continuum for a prolonged historic duration within Africa. In this context, Van Graan (2011) has suggested that acknowledgment of the cultural dimensions regarding development on the international as well as in the African scenario has been performed for at least 40 years. Culture used to be considered as a political instrument during the colonial periods and this had fostered the utilitarian view regarding culture which had been utilized to combat colonialism and the European Cultural hegemonistic perpetuation over the societies of Africa (Kovacs, 2009). During this era of pre-independence movements, the African intellectuals and artists, liberation movement activists and political groups had utilized culture as a method of progression of Pan Africanism (Diouf, 2002). The African context is not unique in terms of the harboring of the views related to the utilization of the potential of culture and creative industries as catalysts for economic progression and development. In the instances of Europe, the driving force of this debate has been necessary to preserve such allocations which could result in the realization of economic, social and innovation-related saturation within the cultural sector (Gray, 2007). According to De Beukelaer (2015) has stated that cultural policies formulated by the cultural ministries increasingly concentrate the focus on the realization of the economic potential ingrained within the cultural sector. This could be identified to have a similar connotation in terms of the acquired evolutionary path throughout Europe since the ministries of culture have focussed incessantly on the financial prospects which could be realized and the commercial value which could be utilized pertaining to culture so that a case for proper budgetary allocation could be justified(ibid).

Pieterse (2010) has also noted that the conventionally accepted distinction in between the developing and developed societies has been relegated to progressive irrelevance with the decline of welfare economies as this has brought it incremental polarisation in between the countries on the basis of constricting public services and knowledge of development has gained increasing significance in this respect. However, it is surprising that this developmental value has been attached to that of the African culture as the prejudices and misconceptions regarding Africa and African culture have been persistently accepted for a prolonged period.

The developmental potential of African culture has been only recently acknowledged. Njoh (2016) has noted that in the late 1950s and early 1960s, developmental economists did consider the traditional practices and customs of Africa as well as various other non-Western social disciplines to be impediments for the realization of modern aspirations of development.

Sorenson (2003) has been one of the most significant proponents of the ambiguity related perception concerning tradition since he has posited that the often acknowledged underdevelopment of the traditional societies has been spawned due to the dearth of powerful catalysts of economic development such as morals, ethical working concepts, capacity for entrepreneurial innovation, capitalistic profit-based market mechanisms, propensities of risk-taking and organizational proficiency management capabilities.

Such thinking is certainly is not prominent in scholarship and international policy, yet its remnants linger in the form of hierarchies of cultural values and taste. Sorenson's view of customs and traditions as an obstacle to development constitutes the many misconceptions out of hegemony of Western knowledge, which prevents the appreciation of other social-cultural orders outside the Western purview. One of these orders relates to the African approach to intellectual property.

Intellectual property and piracy debates

The debates about the intricacies of African approaches to copyright and piracy rights are a demonstration of the distinction of African cultural practice to Western knowledge models of intellectual property.

De Beukelaer, (2017 or6) has observed that the reflection of the dearth of proper scholarly attention to the research of African intellectual property has occurred in the definite incidences of piracy through debates and literature reviews. Despite such complications, the knowledge about the African intellectual property has been slowly improving with the greater measure of literature reviews emerging on the same subject (Larkin, 2008; Lobato, 2010).

As direct instances, Eckstein and Schwarz (2014) have argued that the cultures associated with the Western modernity are inextricably associated with that of piracy and the local histories of such associations have spawned the emergence of the specific notions of capitalism based business operations, property and individualhood which have further contributed to the global practices related to the formulation of copyright regimes (Eckstein and Schwarz, 2014a: 7).

The idea of entanglement is a helpful critique for developing a more nuanced view of different models of intellectual property and piracy. De Beukelaer (2017) has questioned the dichotomous approach of upholding copyright as a universal 'good', and piracy as always 'bad' which regards its eradication as a good. Some scholars are beginning to question the Western doxa of intellectual property and piracy. Lobato, (2010: 246) work has been seminal in arguing that the role of personnel in the process of piracy is equally significant to be comprehended along with the aspect of technology. Lobato has specified that the success of Nigerian film industry, the Nollywood, has demonstrated that stringent application of copyright-related regulations could not be considered to be the preconditions on which cultural industries could be developed and made successful (2010: 246). However, the point is not to valorise piracy, but to argue against a simplistic conception as bad practice. This is further supported by the latest disruptions in the distribution of digital content which necessitates new approaches to accommodate the new platforms and patterns of consumption. For Sundaram (2014: 59), formulation of an enforced distinction between the illegality and legality which could divide pirates from other personnel could never be considered to be an effective solution to resolve such a conundrum since this could render all of the efforts to seriously understand and engage with the incidence of piracy completely ineffective.

Such is the intricacy of African intellectual property whose understanding is contingent on the appreciation of the system of knowledge proprietary on the continent, which encompasses folklore, traditional knowledge and immaterial heritage (Torsen and Anderson, 2010). In Africa as in most traditional societies, the public domain is associated with the indigenous knowledge possession field and this denotes that anyone could utilize such information and the intellectual property is collectively owned by any community (Wipo.int, 2020). This specific logic also outlines the African perception of piracy to be equable to grass root level entrepreneurship within the structure of the informal economy (De Beukelaer, 2017).

The preceding review of the notion of culture and creative industries is germane to this study for an enhanced conception as the host sector of the cultural entrepreneurship of first-generation Africans. The thesis has considered studies of the European and African contexts of culture and creative industries. The literature on African the culture and creative is mainly occupied by the discussions on culture for development and intellectual property. The overall appreciation is the differences in both logics, especially the conception views of knowledge proprietary. The extant scholarship has not considered the experience of transitioning between the two logics, which is important because of the increased migration flows out of Africa. The review of literature on the subject of the cultural and creative industries is incomplete without the consideration of the policy context. Among the vast themes of cultural policy, I particularly consider the aspects that relate to the conditions of the cultural and creative labourforce and the promise of openness for subaltern groups such as the first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs.

Cultural policy in the UK and the egalitarian promise

In this section I conduct a brief review of literature on the development of cultural policy in the UK and the debates surrounding its egalitarian promise. The evaluation of the rhetoric in the governmental cultural policies has the potential to extend the understanding of the political milieu in which new immigrant cultural workers operate. The study of cultural policy remains salient opportunity for asking what lies behind such policies (Hesmondhalgh and Pratt, 2006). Vestheim (2012) states that, it is important to note that the rhetorical statements in cultural policy represent intentions. He goes on to suggest that there may be a gap between intentions and practical results. However, of particular interest to the present study is how the merits of work in the culture and creative industries are presented in policy. I juxtapose the rhetoric in the culture and creative policy with a growing body critique against the conditions of labour in the sector. I specifically consider the scrutiny of the egalitarian promise. First, there is a brief overview of the evolution of the cultural policy in the UK.

The evolution of cultural policy in the UK

The initial social schemes had been formulated to support the financially backward areas during the state-directed inner city-related policies of the 1960s in the embryonic forms which constituted the backgrounds of the cultural policies formulated by the UK (Warren and Jones, 2017). According to Gray, (2000), post-WW2 witnessed the development of a combination of regulations, promotion, protection, and funding to comprise the cultural policies which could be recognized today.The first Minister for Arts of the UK, Jennie Lee, had produced the 1965 White Paper known as the A Policy for the Arts, The First Steps which had been one of the most significant junctures in the cultural policy development history of UK. The white paper had outlined the intention of the Labour Government to broaden the access of to culture for the majority of the populace and this formulated, partially the Democratisation of Culture and this approach was the dominant one in terms of the cultural policies of the UK till the early 1980s (Vestheim, 1994 and Hollis, 1997).Such developments within the UK found proper resonance within the cultural policies of other European countries as well and such effects brought forth the greater democratization of such policies facilitating inclusion as well as an expansion of access involving the projects which had been intended to universalize the appeal and availability of art to the common populace (see McGuigan 2004, pp. 38–39). The problems regarding valuation and funding have persisted since the years immediately following the completion of the WW2 till this date. The most intransigent dispute in this context has been the contentions regarding whether culture could be utilized to obtain financial and social objectives and the role of public finances in this context. The most critical moment of significance in the history of the cultural policies within the UK had been the victory of the New Labour Government during 1997. This era had coincided with the inculcation of the Creative Industries by this new government (Hesmondhalgh et al., 2015). The cultural policies instituted by the New Labour Government have been of specific interest for two particular reasons and these have been the concentration of renewed emphasis on the arts and culture discipline by the New Labour in terms of political self-representation through determined policy parameters, which, were greater in influence than those of the other modern European Governments and, the reconfiguration of the cultural policy based conventional understanding which was performed through concentration of greater stress on the commercial value of creative industries. Such efforts did not jeopardize the subsidies meant for the arts policies in any manner (Hesmondhalgh et al., 2015).The initial social schemes had been formulated to support the financially backward areas during the state-directed inner city-related policies of the 1960s in the embryonic forms which constituted the backgrounds of the cultural policies formulated by the UK (Warren and Jones, 2017). According to Gray (2000), post-WW2 witnessed the development of a combination of regulations, promotion, protection, and funding to comprise the cultural policies which could be recognized today.The first Minister for Arts of the UK, Jennie Lee, had produced the 1965 White Paper known as the A Policy for the Arts, The First Steps which had been one of the most significant junctures in the cultural policy development history of UK. The white paper had outlined the intention of the Labour Government to broaden the access of to culture for the majority of the populace and this formulated, partially the Democratisation of Culture and this approach was the dominant one in terms of the cultural policies of the UK till the early 1980s (Vestheim, 1994 and Hollis, 1997).Such developments within the UK found proper resonance within the cultural policies of other European countries as well and such effects brought forth the greater democratization of such policies facilitating inclusion as well as the expansion of access involving the projects which had been intended to universalize the appeal and availability of art to the common populace (see McGuigan 2004, pp. 38–39). The problems regarding valuation and funding have persisted since the years immediately following the completion of the WW2 till this date. The most intransigent dispute in this context has been the contentions regarding whether culture could be utilized to obtain financial and social objectives and the role of public finances in this context. The most critical moment of significance in the history of the cultural policies within the UK had been the victory of the New Labour Government during 1997. This era had coincided with the inculcation of the Creative Industries by this new government (Hesmondhalgh et al., 2015). The cultural policies instituted by the New Labour Government have been of specific interest for two particular reasons and these have been the concentration of renewed emphasis on the arts and culture discipline by the New Labour in terms of political self-representation through determined policy parameters, which, were greater in influence than those of the other modern European Governments and, the reconfiguration of the cultural policy based conventional understanding which was performed through concentration of greater stress on the commercial value of creative industries. Such efforts did not jeopardize the subsidies meant for the arts policies in any manner (Hesmondhalgh et al., 2015) (ibid). In the years following the Labour watershed movement, different governments and thinktanks have touted the merits of work in the culture and creative industries, particularly its alleged openness to people from all walks of life. The claims have attracted equal scholarly attention to the conditions of labour in the culture and creative workforce. I proceed by considering how some of the UK’s seminal cultural and creative policies considered the conditions of the labourforce in same sector.

Cultural policy and labour conditions

The study of cultural policy has grown to encompass a wide range of themes. However, the entry here is how issues of cultural labour are addressed in the UK’s culture and creative policy. I review the major reports in the recent history the UK cultural and creative policy to assess how they related to issues of labour conditions in cultural and creative industries. I consider the Staying Ahead Report (The Work Foundation, 2007) and the Creative Britain Report (DCMS, 2008) as some of the most important milestones of the recent history the UK cultural policy. According to Banks and Hesmondhalgh (2009) during the mid-noughties, the UK government through the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) were seeking to revive the creative industries policy. The Work Foundation was then assigned by the DCMS in late 2006 to analyse the nature of the creative industries to examine the scale of the sector, the challenges and opportunities. The Staying Ahead Report spelt the ambition to make the Britain the world’s creative hub. However, Banks and Hesmondhalgh (2009) observe that the Staying Ahead reports elided the concrete processes and conditions of creative labour. Instead the report proposed measures for a more sustained focus to stimulate the notion of a business-led, creative economy in a way that characterises some of the policy, the discourse, the aspect of diversity was deployed ambiguously. While the report acknowledged the lack of diversity among the cultural and creative workforce, it did not elaborate the grounds of the absence of certain social groups.

In a similar way the issues of workforce were neglected in the Creative Britain (DCMS, 2008). In the report the government spelt its intentions for the development of the cultural and creative industries from its grassroots forms to the global stage. Here the DCMS committed to ‘work with its non-departmental public bodies to promote a more diverse workforce’ (p. 23). The report attended to the matter of social and cultural diversity by raising concerns of inequitable distribution of internships across ‘socio-economic groups’ (p.23). However, Banks and Hesmondhalgh (2009) contend that the essence of the diversity rhetoric in the report was about diversity in skills. I have deployed the two instances of policy to illustrate a pattern of elision of serious discussion of cultural and labourforce conditions. Both documents issues of culture and creative work are not considered in significant depth.On the contrary, the reports were dominated by hyperbolic promotion of the virtues of creative work.

The promotion of ‘good work’

A growing number of scholars have considered the utopian promotion of work in the discourse in much of the UK’s creative industries policies. Successive governments of different ideological persuasions have promoted the merits of work in the cultural and creative industries. The validation of cultural and creative work is ubiquitous in government and grey literature. The fundamental promise is that the cultural and creative industries embody meritocratic labour market, which is accessible to men andwomen from all ethnic backgrounds and classes (Oakley, 2014). The promise to open opportunities for ethnic groups is particularly relevant to this study. The openness of the cultural and creative labour markets is investigated through the experience of first-generation Africans. The basic premise behind the ‘good work’ image of the cultural and creative industries is that creativity is an innate resource which is bequeathed in spite of ethnic or socioeconomic background. Hense the narrative that creative jobs are supposedly open to everyone (McRobbie, 2015). Citizens are frequently ignored regarding their innate creativity in the discourses of policies and practices of the UK Governments (O’Brien 2014), the suggestive indication that creative personnel capitalizing on their abilities to obtain the benefits off their skills and talents could be considered to be certain but small steps towards such transformative policies. Therefore, creativity could be further considered to be effectively intertwined with the concepts of meritocracy which could prevail upon the modern social and economic organizations (O’Brien 2014, Littler 2013). However, a growing number of sociological and cultural studies scholars have scrutinised the image of cultural work by developing an alternative narrative around the dominant experience of precariousness.They have raised questions about the working conditionsand the claim of meritocracy associated with the recruitment of the cultural and creative workforce. For instance Koppman (2015) has shown how shared cultural tastes correlated with middle class backgrounds are highly influential in hiring practices within the sector. Aslo, Gill (2002) argues that the meritocratic narratives serve to obscure structural inequalities associated with gender and class. In this study the claims are assessed through the category of new immigrant. The question is whether the claims go far enough to benefit even the marginal constituencies such as new immigrant cultural workers. I examine the the efficacy of the cultural and creative industries to meliorate the conditions of new immigrant African cultural entrepreneurs. Through the experiences of first-generation African cultural entrepreneurs, the study contributes knowledge to the bourgeoning debate on the nature of cultural and creative work.

The nature of work in the culture and creative sector

A growing body of scholarship has explored the conditions of cultural work and constituted a critique of the earlier celebratory narrative of the cultural work. Richard Florida often touted the creative as an absolute need for modern cities in a way that was unrealistically fixated on the merits of the creative industries. As a departure from the overly celebratory approach by earlier proponents, a growing body of literature has provided a critical assessment of the nature of cultural work.One of the critical studies by Michael Scott (2012) represents cultural entrepreneurship as prone to high failure rates and holding multiple jobs to maintain cultural production. He adds that a common characteristic is engaging in cultural production while undertaking other paid work away from the cultural sector. While Scott's portrayal of cultural entrepreneurship may not be accurate in every instance, it, however, provides a dramatic contradiction to ideas of balance between economic goals and retention of cultural integrity of the previous arguments.A major category of research in this debate has discussed the pervasive features of creative labour: precarious employment, non-paid work, gendered disadvantages, dense social networks, and multiple-job holding to sustain both livelihoods and cultural production (Gill and Pratt, 2008; Hesmondhalgh and Baker, 2011; Leadbeater and Oakley, 1999; McRobbie, 2008; Menger, 1999).A prominent characterisation of cultural work is individuated working patterns. The figure of a flamboyant auteur, which is mostly associated with being an artist, film-maker or writer, is a pervasive model of an individuated working pattern (McRobbie, 2018). Some studies have alluded to autonomy as a pull factor of the sector for classes who experience barriers in the formal job market. Gill, (2002) argues that informality of work practices and relationships within project-based new media was regarded as a major attraction of the work by the vast majority of the respondents. According to McRobbie (2002) the media has often celebrated creative artist as uniquely gifted ‘stars' which contributes to a process of individualization, a social category of people who are increasingly disembedded from ties of kinship, community and social class (McRobbie, 2002). For Giddens (1991) this class works in in a deregulated milieu, ‘set free' from both workplace coalitions and from social institutions (Giddens 1991).

The preceding critique of cultural entrepreneurship raises a counternarrative the image of good work which dominates cultural policy literature. Specifically, the individualised working patterns have been linked with the reproduction of disadvantages especially along gender. Informality has spawned some problems for various women involving a range of different experiences such as gender-discriminatory assumptions, inappropriate working conditions, and interactive environment, male-dominated working teams, etc(Gill, 2002). I note that most of the preceeding arguments are based on the experiences of the indigenous labourforce. The studies of the nature of cultural work are marked by the absence of experience of ethnic, cultural entrepreneurs such as new African immigrants. Besides, part of the promise of culture and creative industries is often cited as their openness to ethnic minorities. Therefore, it is germane to evaluate these claims through the experience of African cultural entrepreneurs.This thesis contributes an ethnic dimension to the debate of the condition of work in the cultural and creative industries. The ethnic cultural entrepreneurs experience the directimplication of the in their localneighbourhoods.Therefore, in the coming section I consider discussions on local cultural policy through view that it is at the local government and community level that questions of policy implementation and actual effects manifest (Ponzini, 2009).

Local cultural policy