Advancing Low Carbon Procurement

Introduction

The previous chapter looked at drivers, barriers and enablers of LCP (Low Carbon Procurement) in the public sector taking a two group perspective. At the end of the chapter key themes were discussed at a wider level of unpacking LCP. Cycle 3 has been designed from findings from cycle 2. At present knowledge, training and skills are barriers in Wales. The aim in cycle 3 is to engage, share knowledge with the aim of influencing change. Cycle 3 involved working with NHS Wales’ procurement function/team. The focus of the cycle 3 built on the current barriers:

Lack of understanding of LCP and how it relates to the procurement process.

Limited/lack of training provided

Procurers referred to one way communication and lack of support.

Also different people are involved in the process and need to be involved to understand e.g. central procurement, local procurement and hospital based (life cycle of a product/service)

There was an unresolved point in the findings of cycle 2 about whether procurers needed understand of LCP to implement it or whether the process just carries it forward? I think procurers need a level of understanding of LCP to implement it which is shared by the work of Correia et al (2013).

The research question for cycle three is: how might forms of engagement influence knowledge transfer and change?

The objective of cycle 3 is to take the findings and discussion from cycle 2 and make changes to see if this can accelerate learning and the implementation of low carbon procurement in Wales. Chapter five contains the research design for cycle three. Two groups of participants took part in the workshop, the structure varied slight due to time restriction between the two workshop groups. The workshops were promoted as interactive with the aim to make change. Aids were used to support the workshops PowerPoint slides such as a physical ‘globe’ ornament, flip charts, regular open discussions, post its, video and cards. The activities and findings from the workshop will now be presented in order to answer the research question. Firstly, a presentation from the activities which took place during the workshop (as outlined in the research design) will be presented to provide insight.

Knowledge checks pre-workshop

Association of carbon dioxide

Participants were asked to write a word or phrase on the word that they associated with carbon dioxide (carbon). These were displayed on the wall and the researcher with the participants.

Pollution

Fossil fuels

Greenhouse effect

Transport

Energy Consumption

Harmful

Topical

Greenhouse effect

Gas

Greenhouse gas

Global warming

Emissions

Gas

Waste product

Buzz words

Latest hot topic

Greenhouse gas

Gas

Carbon reduction

Global warming

Climate change

Part of the sustainable jigsaw

Vehicle emissions

Vehicle emissions

Environmental impact

Emission from production

Emission from transport

Carbon footprint

Global warming

Fuel

Greenhouse gases

Damage to the environment

Climate change

Environment

Transport

Environment impact

Energy used

Cost of foods

The rainforest

Emission

Greenhouse gases

Footprint

Knowledge category

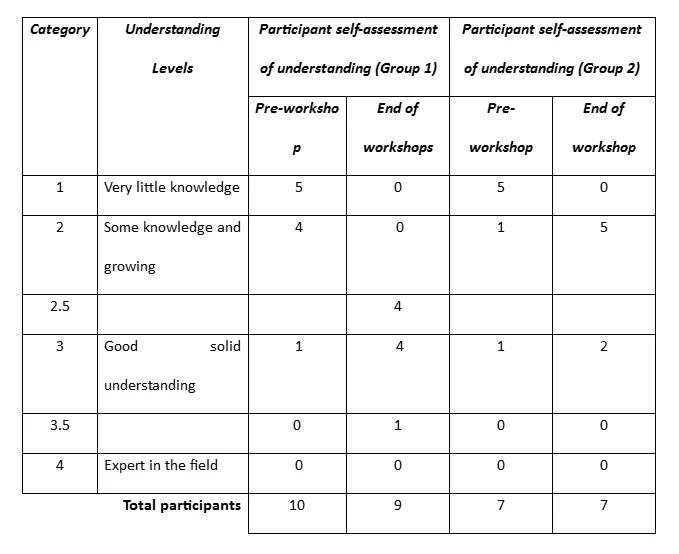

Individuals were asked to physically stand in one of four categories allocated in the room that represented their understanding of LCP. The researcher read out the label e.g. category 1 which represented ‘very little knowledge’ of LCP. The results were recorded against the table and have been displayed below.

The table shows participants had a limited understanding of LCP. 50% of group 1 allocated themselves to ‘very little knowledge’. Group 2 had 72% of participant allocate themselves to that category. A clear difference between the two groups which was not intended was that group 1 did not have local procurement or hospital based employees as they did not attend, there was a drop out. Group 2 have 5 local/hospital based staff attend after discussions allowed the original drop out. Another observation is that one person in each group allocated themselves to having a ‘Good solid understanding’, for group 1 this was the Energy Manager and for group two this was the Environmental and Sustainability Officer. Both explained they worked closely in the area and had a better understand what it means and the impact.

Activities

The activities part of the study involved participants engaging in activities that would make them aware about the low carbon procurement. The activities were aimed to bring to their attention how the procurement process contributes to carbon emission. After providing information about LCP through PowerPoint, a video around the carbon footprint (including information on lifecycles of product and services) participants were asked to complete activity one in pairs.

Activity One

Part A:

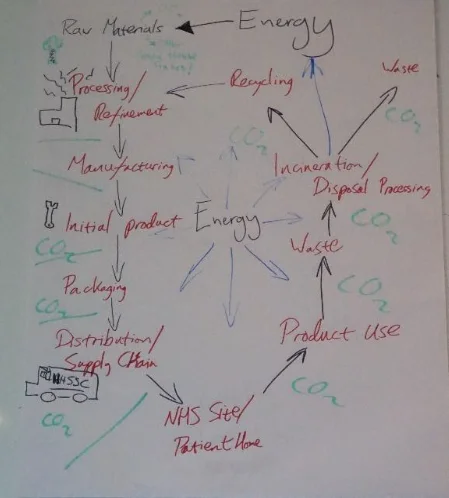

Please draw the life cycle of a key product or service you often buy for the NHS?

In pairs pick one of the product/service drawn. Discuss with a partner where you think there might be carbon emissions emitted into the atmosphere?

Participants were encouraged to be creative to draw the life cycle. Below is an image of the lifecycle of a surgical equipment from raw material to the end of life. This pair explained to the group from the information shared through the PowerPoint slides and video they become aware carbon feature through the whole life of the product.

As part of the story-telling feature of AR participants were asked to freely express themselves to tell the story of the product like cycle answering the two question for the activity.

The pair provided a flow chapter format of their product life cycle. Though this process they noted carbon was present at all stage. This explained they never considered carbon in that way before.

Arrows were used to represent the order of the life cycle

The lifecycle draw above is broken down into detail

Co2 was used to represent where they understood carbon may be present.

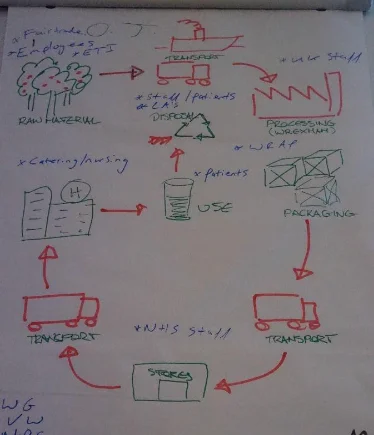

Another team/pair example produced was the ‘orange drink’ which has appeal of lid.

This image tells a details usual story of an orange juice. Again the participant used arrows to show the flow of the lifecycle

Each stage had an image to present the activity e.g. ‘packaging’. The pair noted co2 was present through the whole process but maybe more present at some stages than others. The participants also used this diagram to illustrate stakeholder

Part B:

Complete the Sustainability Risk Assessment (SRA) in pairs briefly.

Discuss which parts of the SRA looks at carbon dioxide and whole life cycle?

What are your thoughts about the SRA?

As part of this exercise procurers were asked to use a hard copy of the SRA (Sustainability Risk Assessment, procurement tool/document) to mark where carbon would be covered. The focus was make the connection between carbon and the tools.

Activity Two

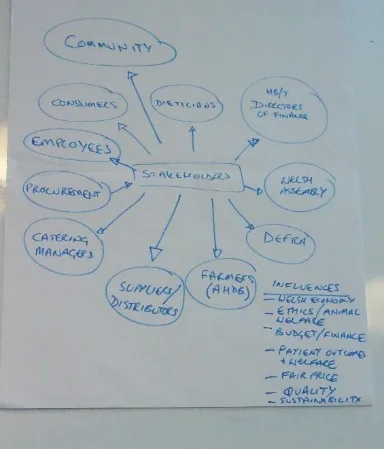

Taking the life cycle approach in pairs write down your internal and external stakeholders for the product/service selected in activity one.

How might they affect or be affected by the procurement of the product/service?

What helps and hinders?

The pair that looked at ‘milk’ as a product noted their stakeholders on the image below. They explained to the group that there was a wide range of stakeholders involved.

The group outlined stakeholders through the use of across and bubbles. The explanation was that each stakeholder has a group and they wished to show the connections through the use of bubbles.

At the bottom of the diagram they listed the influences they have and went to make connection.

Activity Four

As the focus of the workshops were to share knowledge and simulate change the researcher asked the participants to complete the final task around change. Benefits of change. The task was used to get people to put knowledge into practice. The research brought the participants together to build a discussion about change to empower them.

This pair selected the procurement of fruit and vegetables. They showed how they would implement this into the procurement process.

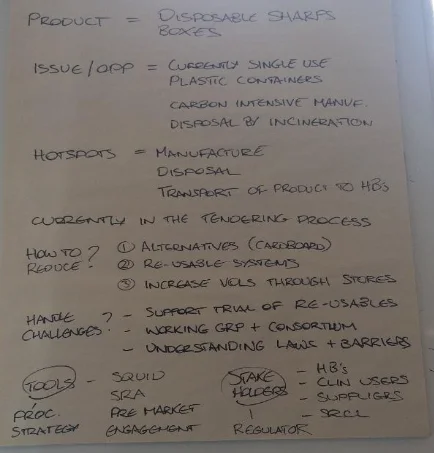

This pair used disposable sharps boxes which are used in NHS hospitals. This is already going through the tender process. They discussed changes they could make during the process and challenges.

Closure of workshop

At the end of the workshops participants were asked to repeat the knowledge check (mentioned earlier) and provide voluntary feedback and also answer two questions:

How would you explain Low Carbon Procurement to someone?

What have you taken away from this workshop?

The purpose of this was to get an understanding of how the participants digested the material within the workshop. Data was gathered through words/phrases that come to mind as noted on the image below

Using less of something, especially carbon intensive products

Something to care about

Future proofing

Identifying the “hotspots” that can drive greatest efficiency to reduce carbon.

Hope

Considering all aspects of life cycle and challenging misconceptions (e.g. delivery of food is the biggest problem)

Target, measure, achieve

Greenhouse gases

Manufacturing process, transportation, disposal, gases…cradle to grave process

Expense (up-front) is looked at first and not the whole picture

Global challenge

Challenge

Opportunity to make change

Shorter supply chain reduce carbon > better for all

ISO standards > measuring use > strategies to reduce > measure benefits

Sustainable future

Efficiency, efficiency

High level of comment? (i.e. needed)

Whole life-cycle

£ vs Carbon

The phases/words varied but touched of the idea of hope and sustainable future to the challenge and barrier still at hand connected to the commitment needed and cost of low carbon products. Cost is something that was mentioned din cycle 2 and consistent with the work of Walker and Brammer (2009; 2011). After the workshop ‘cost’ i.e. price of low carbon products/services was still referred to as barrier and people not looking at the whole life-cycle/wider picture.

Feedback

At the end of the work feedback was given. Please find below a presentation of the feedback.

At the focus of the workshop was change. Knowledge checks were completed immediately after the workshop. Table 7.3 displays the outcome of the knowledge checks pre and at the end of the workshop.

Knowledge checks post-workshop

Table 7.3 displays participants knowledge, self-evaluated pre and post workshop. The table illustrates knowledge has improved with sharing knowledge and providing training. Group 1, who had 6 hours of workshops made better improvements as opposed to group two who only took part in hours of workshops. One participants from Group 1 did not attend the second workshop which gather self-assessment post workshop. The objective of the data is not to purely statistically calculate but report the finds to give some understanding. Following the workshop the research meet the management at the NHS to discuss the workshop and feedback from individuals.

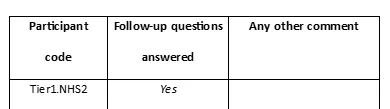

Mid-range change - follow up

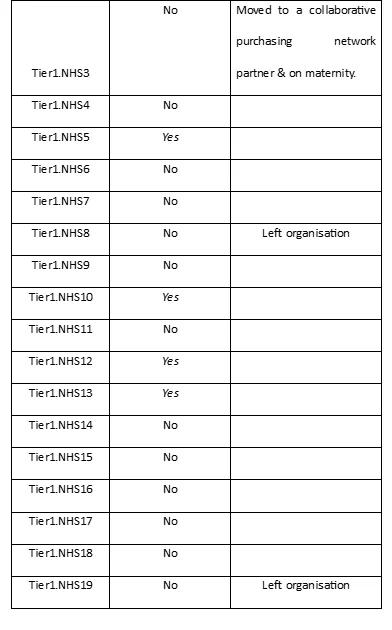

Participants were followed up after 12 months to understand if mid-range change had taken place in their procurement activity. Table 7.4 outlines a breakdown of the follow up made with participant.

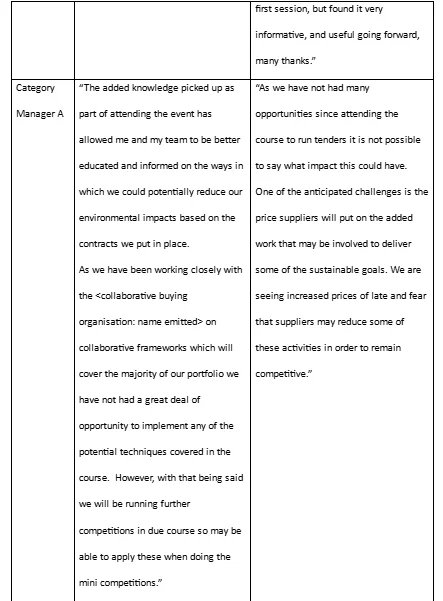

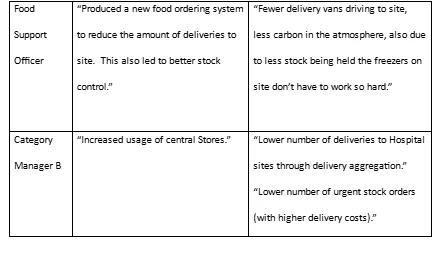

Table 7.4 outlines only five responses were received from the eighteen participants’ contacts. Three people were recorded as leaving company from shared services department. The researcher was informed figure of ‘leavers’ would be higher but point of contact did not have information of employees outside of shared services. Issue of resource lost. From the five respondents four are part of the central procurement team and one is locally based in a hospital. Table 7.5 displays responses received to the two questions asked.

The participants here indicate the steps they are taking in order to implement low carbon procurement. For example, Category Manager C indicates that they have begun asking more focused questions from their supply base, questions which are aimed to determine the level of carbon in the products they purchase. This is aimed to help them identify products with low carbon levels. Category Manager A indicates that they have focused on the tendering process to ensure that they award tenders to organizations that supply low carbon products. Category Manager B indicates that they have increased central stores to lower the number of deliveries. The actions of these participants indicate the importance of awareness. After becoming aware of how their procurement processes contributed to increased carbon emission, they set in motion actions that would help reduce it. This shows the importance of awareness in initiation and implementation of low carbon procurement.

Additionally, participants were asked to voluntarily provide any additional information they thought would be useful to know. Category Manager B and Category Manager C provided the information below.

This is part of a long-running programme to drive as much bulk stock via our distribution stores in Bridgend, Denbigh and Cwmbran. As part of every tender, we look at what is currently in Stores and what is being purchased that could potentially be put into Stores. We work with colleagues from Stores in order to identify suitable products (gloves, gowns and drapes are a good example from my areas).

In addition to this, we have been actively removing items that are in Stores from each Health Board’s direct order catalogue. This helps prevent users from ordering direct from supplier when they should be purchasing via Stores.

All of this helps us to rationalise what is used in hospitals by limiting choice to the contracted products. Additionally, it reduces the number of deliveries by couriers to Hospital sites required which reduces on-site congestion and provides the opportunity to reduce storage required at hospitals.

We have not actively pushed additional products into Stores over the last few years due to space constraints, but this is changing soon as they are clearing out unused products to make room for faster moving lines.

To give you an example of the scale of this:

> In the last 12 months, NHS Wales purchased 127.6 million examination gloves (or pairs in the case of sterile ones)

> Of these, 89.5 million were distributed via one of our Stores (36,800 individual orders)

>This means that 70% of our gloves are distributed via Stores

In theory, this means that 36,800 deliveries aggregated with other products to reduce the number of courier deliveries. While it would be almost impossible to put a number on exactly how many deliveries have been removed.

We’re trying to use the tender process to increase awareness. During the procurements we have used the questions in are for plastic based products and due to the nature of their use the recycled plastic can only be used in certain circumstances. We’re trying to gather more information about this through the process and to use contract management as a vehicle to monitor improvements during the contract’s life.

Ultimately a tender could be won or lost on supplier’s responses to these questions. NHS Scotland have adopted a similar approach so supplier’s need to show willing to improve processes and increase recycled content where appropriate to win tenders.

One of the projects is circa £700k p.a. and the other circa £70k p.a.

We have working groups that will monitor any potential improvements on recycled content and carbon footprint for one and the other will be by way of an annual report. They’ll be conducted by procurement (our team) with the stakeholders.

NHS Scotland’s approach was for one specific project that I contacted them about, I’m not sure how this came about or if it is something that’s widely adopted.

The information provided by Category Manager B and Category Manager C shows ways in which low carbon procurement. According to this information, one way in which low carbon procurement can be achieved is through deliveries. Category Manager B indicates that he focused on reducing the number of deliveries so that carbon emission through transportation. Transportation is one of the main contributors of carbon emission considering that most locomotives use fossil fuel to run. Reducing deliveries is thereby one of the means through which low carbon procurement can be achieved.

However, while reduction in deliveries helps to reduce carbon emission, it creates another problem which is the problem of storage. Category Manager B indicates that in order to reduce the number of deliveries, he focused on reducing direct orders by removing products from the Health Board catalogue. If the number of orders remains, then the stores have to hold more inventory in order to be able to cater for the increased demand due to elimination of direct orders. Since no additional space has been added, then it is likely for Category Manager B to experience problems in future especially in cases of an increase in demand. To deal with this problem, there is need for Category Manager B has to study the market and develop strategies of how to handle changes in demand. However, the organization is going in the right direction with regard to how it is handling the situation. For example, Category Manager B indicates that they are planning on clearing out unused inventory in order to increase the speed with which the goods move. This will not only help the organization to ensure that its stores hold relevant products, it will also reduce the cost of operation which comes from holding irrelevant inventory.

Category Manager C focuses on tendering process as well as the number of deliveries. This approach is more efficient because it addresses all aspects of a product’s lifecycle. By examining the tendering process in order to bring in products which are low on carbon, the organization helps to reduce carbon not only during the procurement process but also in the production and usage of product.

Discussion

There are a number of deductions that can be made from the findings in this study. One of them is the main barrier to low carbon procurement is lack of awareness about the amount of carbon that is normally released during the procurement process (Asselt et al 2006). For instance, at the start of the exercise, a total of 10 individuals out of the 17 participants indicated that they had very little knowledge about LCP. This implies that the lack of LCP in organizations is not due to inability of individuals involved in procurement to implement it. Rather it is the lack of awareness among them about the existence of such a concept (Li and Geiser 2005). It was also established in this study that there was also lack of knowledge concerning how much the procurement process contributes to carbon emission into the environment. The participants were not aware that various stages of a product’s lifecycle contribute to carbon emission into the environment (Rimmington et al 2006). It is only when they were asked to draw the lifecycle of the products that they purchase that they became aware about how each stage of the product’s lifecycle contributes towards the overall carbon in the environment.

Lack of awareness about low carbon procurement and how the procurement process contributes to the overall carbon emission is a factor that has generally been overlooked in the existing research studies. Most of the existing research studies have focused on factors such as leadership, cost, and training (Dawson and Probert 2007). Majority of the existing research studies point at the lack of quality leadership, high cost, and lack of training as the barriers to low carbon procurement. However, the findings in this study indicate that the main barrier is lack of awareness and that there is willingness among individuals and organizations to put in place measures that would ensure low carbon procurement is achieved (Thomson and Jackson 2007). This is revealed in this study from the follow-up responses from participants. During the follow-up exercise, it was discovered that various participants had already put in place measures that would promote low carbon procurement in their respective organizations. For example, Category Manager C indicated that to promote low carbon procurement, they had begun asking their supply base to focus on supplying low carbon products. The Food Support Officer indicated that they had introduced a new ordering system to reduce deliveries on site.

The issue of training also came up in this study. It can be deduced from the results that with significant training, low carbon procurement can successfully be implemented in business organizations (Bala et al 2008). For example, after being given some form of training, a number of participants initiated a number of practices in their organizations to bring about low carbon procurement. For example, Category Manager B removed some items from the direct order catalogue in order to compel individuals to purchase from the store. This was aimed to reduce the number of deliveries which had increased significantly due to the direct orders.

As indicated before, the issue of training in relation to low carbon procurement has been investigated significantly. A significant number of researchers have pointed out that lack of training is one of the factors which have acted as a barrier to the successful implementation of low carbon procurement. For example, a survey carried out by OECD (2015) reveals that one of the factors which have hindered successful adoption of low carbon procurement in business organizations is lack of the necessary skills among the various players involved in the procurement process due to lack of the necessary training. The idea of lack of training as a barrier to low carbon procurement is also pointed out in a study by Daddi et al (2012). In their study, Daddi et al (2012) point out that low carbon procurement has failed to be implemented even in organizations which are aware of its importance due to lack of training.

The lack of training even in organizations with full knowledge about the environmental benefits of low carbon procurement might be due to cost involved. While it was not addressed in this study, cost is an issue that is central to all business organizations whenever there is consideration of introducing new changes. Introduction of changes in an organization, in most cases, involves the use of resources (Bolton 2008). In the case of introducing low procurement process, there is need to the relevant employees in the new changes, which can be costly. In most cases, companies only introduce new changes if they would result in improved profitability. In the case of low carbon procurement process, the focus is on the environment rather than the performance of business organizations (Rolfstam 2009). This is thereby likely to discourage the management from using resources to train employees so that they can gain the necessary knowledge and skills to implement low carbon procurement.

Impact of increased awareness and training

From the results in the study, it can be seen that increased awareness and training about low carbon procurement has a positive effect with regard to individuals and organizations adopting and implementing strategies that would ensure increased level of low carbon procurement (Walker and Preuss 2008). After the participants in the study had been made aware of and given some form of training, a significant number of them tried to implement what they had learnt in their organizations. Awareness and training can thereby considered to be drivers of low carbon procurement.

However, it should be noted that awareness and training alone cannot result in low carbon procurement but rather the knowledge gained through training needs to be implemented. The problem is many people or organizations are usually not willing or not able to implement the knowledge gained through training (Sonnino 2009). For example, in this study, only 5 participants initiated change in the procurement process. This could have been influenced by a number of factors. One of them could be the position an individual holds in an organization. While an individual might be working in procurement, their position might not allow them to initiate any change in the process (Sporrong and Bröchner 2009). On the other hand, the management might be unwilling to adopt their ideas. For instance, a review of the participants who initiated a change in the procurement shows that they are individuals who hold senior positions in their respective organizations, positions which allow them to initiate changes in the way the organization operates.

Another crucial point to note from this study is that the success of low carbon procurement is determined mainly by the procurer. The procurer is in a position to dictate how the procurement process should be carried out (Walker and Brammer 2009). This can be seen from the few participants who decided to initiate changes in their procurement process. For example, Category Manager C indicated that after learning about low carbon procurement, they changed tact and began asking their suppliers about the products they sell in order to determine the ones that have the lowest level of carbon (Akenroye et al 2013).

Lastly, results in this study indicate that low carbon procurement can be achieved mainly through a shift in ordering and purchasing process (Molenaar et al 2010). A change in the way products are ordered can result in reduced carbon emission. For example, a reduced number of orders help to reduce the level of carbon emission due to transportation. This is because it reduces the number the number of deliveries thereby lowering the amount of carbon emitted in the atmosphere from delivery vehicles (Bratt et al 2013). In essence, material entering business organizations passes through the procurement process. As such, companies are in a better position to influence the procurement process and help conserve the environment through encouraging low carbon procurement process (Brammer and Walker 2011). Companies have the ability to integrate the sustainability criteria into the procurement particular with respect to their purchasing decisions or supplier selection process.

Implementation of low carbon procurement

This research study reveals that in implementing low carbon procurement, companies are required to increase the sustainability criteria in procurement. It can be noted from the results that sustainability criteria can be tightened either in the purchasing decisions or in the supplier selection process (Palmujoki et al. 2010). A supplier’s environmental performance can be evaluated at either the corporate or the product level. However, in the procurement process, companies can evaluate the environmental performance of their suppliers at the product level (Burchard-Dziubiñska and Jakubiec 2012). This is evident in this study with participants who decided to introduce changes in their procurement processes. These participants focused on the properties of products with respect to carbon level.

In this study, the focus has been on awareness and training and how their presence enhances the adoption and successful implementation of low carbon procurement. However, it is important not overlook the fact procurement is a complex process that involves various players and which face many barriers other than just the lack of awareness and training (Erridge and Hennigan 2012).

It is also important to understand that the procurement process is normally aligned to a company’s business strategies. Consequently, any adjustment to the procurement process has an impact on the overall operation of a business and as such, a company might be compelled to adjust its business strategies with the adjustment of the procurement process (Zhu et al 2013). Most business strategies centre on making profit and gaining a competitive advantage in the market. Companies thereby develop procurement processes which are aimed enhancing these goals. In addition, companies adopt procurement processes which assure supply of the products they need (Kanapinskas et al. 2014). AS such, most companies are normally unwilling to adjust their procurement process for fear of losing their competitive advantage, disrupting their supply, and reducing their profitability.

Unwillingness of companies to implement low carbon procurement is one which is generally agreed among researchers. However, contrary to common belief that low carbon procurement is costs more, evidence from research indicates the low carbon procurement can actually result in reduced cost of operation for a company (Diófási-Kovács and Valkó 2015). This can also be deduced from this study from the actions of the participants who decided to implement aspects of low carbon procurement in their procurement process. For example, in trying to enhance low carbon procurement in their organizations, Category Manager B and Category Manager C used strategies that were aimed to reduce the number of deliveries. This has the ability to reduce the cost of operation not only for the procurer but also the supplier who can reduce the cost of transportation due to reduced number of deliveries (Gelderman et al 2015).

Barriers

As indicated before, procurement is a complex process which involves many players and is faced with various barriers which make changes in the process. The procurement process faces both external and internal barriers and as such, for change to be successfully implemented there is need for a company to deal with these barriers (Testa et al 2012). Some of the external barriers facing the procurement process include the end customer, supplier commitment, environmental orientation, and industry. Among these factors, supplier commitment and end customer are the most significant.

Supplier commitment is the willingness of the supplier to change their product or operations in order to enhance low cost procurement. As discovered in this study, the procurement process does not only involve the movement of products from the supplier to the procurer but also includes the products themselves (Meehan and Bryde 2011). In order to achieve low cost procurement, focus has to be on the product as well as the movement process of the products. For instance, as evident in the results in this study, a procurer has to analyse the products and choose those that result in the lowest carbon emission during production and use by the customer (Ahsan and Rahman 2017). As such, if products produced have a high level of carbon, then the procurer has to ask the procurer to change the products and supply those which have a lower carbon level. However, this might involve introducing major changes on the part of the supplier, changes which might be very costly. In this case, the supplier might be unwilling to initiate those changes (Oruezabala and Rico J2012). In situations where the supplier power is high in the sense that supplier have the ability to raise the price of their products, reduce quality and availability of products, then the procurer is likely to fail in achieving low carbon procurement particularly in situations where there is need to change or adjust the product.

The end customer is also an important factor which can act as a barrier to low carbon procurement. As indicated before, a change in the procurement might involve changing or adjusting the product. However, customers may not be receptive to these changes (Zhu and Geng 2001). Customers may prefer the previous products and a change may make them to look for other sellers. This may thereby make a company to lose its competitive advantage in the market. Apart from external factors which act as barriers to successful implementation of low carbon procurement, there are also internal factors which may also hinder the ability of a company to initiate changes in its procurement process (Chiarini et al 2017). These factors include cost, top management support, collaboration, and internal buy-in and knowledge.

While the implementation of low carbon procurement may result in reduced cost of production as evidenced in this study, it is possible that implementing change in the procurement process to low carbon procurement may be costly (Nijaki and Worrel 2012). The cost involved may include changing the supply chain logistics, training employees, and building new storage facilities. If the cost is very high, companies may be unwilling to initiate the change. The success of project in a company is dependent on the top management. The top management makes decisions on whether a project is viable or not. In the case of low carbon procurement, the top management has to be convinced that apart helping to conserve the environment, the process will also help enhance a company’s profitability (Testa et al 2016a). If the management feels that introducing low carbon procurement will not only be costly but will not help the company improve its performance in terms of sales and profitability, then it is unlikely to support the initiative. On the other hand, if the management feels that introducing the process in the company will have an overall positive on the company, then it is likely to support its implementation and avail the necessary resources (Gelderman et al 2017).

Collaboration among various departments in a company also determines how successful the implementation of low carbon procurement will be (Meehan et al 2017). While the top management might support the idea of introducing low cost procurement in the company, lack of collaboration among the various departments may make it hard for the process to be implemented (Rahman and Islam 2017).

Lastly, the successful implementation of low carbon procurement in a company relies on the internal buy-in and knowledge (Keulemans and Walle 2017). For any change to be successfully introduced in an organization, they must be the internal buy-in which involves the change being generally accepted in the company (Grandia et al 2015b). Acceptance of the change will make employees to be willing to take part in ensuring successful implementation of the change. In addition, they must have knowledge about what the change entails so that they can understand the part they need to play.

Basically, as shown in this study, awareness and training are very important factors in the implementation of low carbon procurement because they allow companies to have knowledge about how the procurement process contributes carbon emission into the environment and how to successfully implement low carbon procurement (Roman 2017). However, it should be noted that the procurement process is complex and involves many players and for it to be implemented successfully, a company must overcome many barriers.

Summary

This chapter concludes that with knowledge sharing and training individuals can make change. Change can be viewed over short term, medium term and long-term change. This chapter closes to note that with relevant training procurers are able to make change into their procurement activities. In honestly of the research it is important to know that barriers still remain and procurers though able to implement LCP are faced with barriers such as macro level conflict between legislation and austerity measures in place.

What Makes Us Unique

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts