A Journey in Non-Medical Prescribing

I am a Clinical Nurse Specialist working in dermatology, writing a critical reflection on a prescribing decision whilst a non-medical prescribing student (NMP), undertaking a prescribing course under the supervision of a Designated Medical Practitioner (DMP) which is planned around the Royal Pharmaceutical Society competency framework (RPS 2016). Using a patient-centred prescribing approach I will look at the social economic, cultural, commercial and governance influences on ethical prescribing practice. The aim of this piece is to reflect on current practice and use this to develop personal practice in the future. Due to confidentiality the patient has been given the pseudonym- Harry- to protect their anonymity in accordance with the Code of professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses and midwives (Nursing and Midwifery Council, NMC 2015). Due to word limitations a description of the scenario is provided in Appendix A. On qualifying as an NMP, I will be permitted to prescribe medication- within an agreed clinical management plan- for patients who have already been diagnosed and assessed by an independent prescriber. The Department of Health (DOH, 2006) states that a practitioner can be a dentist, nurse, pharmacist, dietitian and paramedic, (RPS, 2016; DOH, 2006; Heath, G. and Bradbury, H. 2014 57). Reflection is to learn from the experience, a necessary path that one is required to take, (Jasper, 2013).

Looking back at the situation, my patient- Harry- was very upset about his severe psoriasis, he had been taking methotrexate (MTX) described by the Joint formulary committee (2018) as a folic acid antagonist to help reduce symptoms of psoriasis. Harry’s condition (Psoriasis) is described as a chronic, painful, disfiguring and sometimes disabling inflammatory skin that has no cure, it comes with unfavourable effects on the individual- physically, emotionally and socially, (World Health Organisation, WHO 2016). (See Appendix A).

Reflecting on the consultation, Harry was severely affected by his skin complaint, he displayed signs of distress, agitation and anger; I remember thinking I am not sure how this consultation will go. To begin with, I felt it was important to find out more about his feelings, goals and expectations of the appointment, a fundamental part of any consultation as highlighted by Berlin and Carter (2007). I recall asking what Harry wanted to achieve from the consultation and he said, “Clear skin so I can lead a normal life.” This resonated with me; Kaufman (2008) affirms an effective communication is necessary for the rapport to be established in patient centred care. Additionally, McKinnon (2007) described this as an important process that helps take into consideration a patient’s personal beliefs and viewpoint regarding their care as an approach to strengthen the prescribing decision. Another part of patient care is to give them the time they need to express their concerns as highlighted by Roberts (2013, 25-27). Harry was given time to communicate his thoughts, even though in the back of my mind I knew there had to be a time limit as I needed to see more patients- due to the clinic already running late.

The patient’s behaviour when seeking medication is often based on factors such as the socioeconomic orientation of the patients. Despite having to come to terms with the medical conditions, as well as the accompanying pains, patients’ behaviour is often motivated by other reasons that have substantial influence on their condition. During my encounter with Harry, I noticed that besides the psoriasis condition, he was also facing some challenges that largely affected his interaction with people, and me as his nurse. The initial encounter portrayed that Harry was frustrated and aggressive, and he was reluctant to establish a relationship with me. On further enquiry, I managed to establish that Harry was grappling with problems at his workplace and his absence from work due to the sickness affected his work. Harry conceded to having frustrations and opted to stay secluded. As a nursing practitioner, I knew that obtaining information from him would only be possible having established a therapeutic relationship with him (Tagney, J. and Younker, J. 2012, 588-594 and McKinnon 2013). During the interactions, Harry shared his feelings, concerns and how it impacted on his life, expressing social isolation and a preference to stay secluded in his room.

This led me to consider the socio-economic aspect, literature shows psoriasis sufferers have decreased job standings, lower pay and a compromise life due to the problems associated with the condition, (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE, 2012). World Health Organisation (2016) strengthened this fact further by disclosing psoriasis as a causation that affects work due to the psychological impact the disease can create including shame, low self-esteem and higher levels of anxiety and depression effecting day to day life and work. A study in Germany (Augustin M et al 2008) highlighted severe psoriasis sufferers such as Harry lost on average 4.9 working days annually, and the incidence of hospital stays were also higher than psoriasis sufferers with a mild form, thus affecting the financial load for society in general and patients economically. In addition, (Barea, A. and Reeken, S.2018 p28) state patients die earlier than the broader community because of the condition.

Reflecting in action (Schon, 1983), I was required to make the right decision based on Harry’s situation and expectations. It is well documented that patients can become anxious about treatment, which leads to lack of concordance (Savage et al 2018). Therefore, giving the relevant information about treatment options both verbal and written can aide Harry to make an informed choice and a rational decision as highlighted by RPS (2016). There are four moral principles that are fundamental to nursing: justice, autonomy, beneficence and non-maleficence, (Beauchamp, T.L. and Childress, J. F. 2013) and these were taken into account when we discussed treatment options. I had an ethical obligation to advise and inform Harry of the benefits and possible side effects of treatment options, allowing informed choices to be met (Barber et al 2011).

My awareness that his medication failure was highly likely due to lack of concordance was a source of concern for me, (Felzman, 2012; Royal Pharmaceutical society, PS 1997). Dignity and respect were achieved and were paramount throughout our consultation (RPS 2016). Harry became very receptive to trying a new treatment. The final part of the consultation involved an agreed shared understanding and the verifying that he was happy with the plans we made, highlighted as important by Gill & Murphy (2014). The prescribing decision was to start subcutaneous adalimumab, a well-established and well tolerated medication approved in 2008 (NICE 2008) and a medication I was confident with due to past experiences.

As a nursing practitioner, I was aware that considering Harry’s condition, he may have difficulties meeting his medical needs. Having problems at work, and leading a secluded life, Harry would easily be a victim of health inequalities. The socio-economic status of the patients has been identified as one of the determinants of health inequalities, with patients from low socioeconomic status having difficulties meeting their healthcare needs (Bernheim et al. 2008).

Influence of Governance

Clinical governance perspective in the National Health Service (NHS) is to adhere to policies and pathways such as high cost drugs pathway for psoriasis (2018). Culturally the NHS invested very little into skin conditions according to WHO, (2016 5), believing the conditions have generally cheaper treatments, because historically they have viewed skin disease as a minor condition, (All party group 2013) and partly because treatments historically where inexpensive. The treatment option for Harry was expensive. The introduction of biological treatments, a more effective costly option has transformed many of the psoriasis patient’s quality of life that I have nursed. 40% of hospitals in 2009 cited barriers to funding such drugs as stated by the all-Party group (2013), even though NICE had approved them. Most of the patients I see have a diagnosis and are on long term medications for lifelong conditions. Psoriasis affects 2-4 % of the world’s population, it has no cure, and strong information gathered has proven that patients with these conditions have more negative life impact than those who have cancer, heart condition and diabetes (Christopher’s, E, 2001, 314–320).

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, (NICE 2019) pathway for biological therapy guidance states that the patient is required to have failed at least one systemic therapy before being considered, Harry failed several, but this was more likely due to lack of concordance and I explained that that was my thinking about him. Governance and regulatory bodies play a crucial role regulating the provision of healthcare. For instance, the NHS is on the forefront of advocating for patient centred approach in provision of healthcare. As a nurse, I borrow my practice in managing the condition of Harry from such guidelines.

Healthcare organizations such as NHS and NICE (2019) are answerable and linked to corporate governance in the provision of their services. This therefore implies that a broad framework is adopted to enhance the clinical operations. As a practitioner, I relied on the professional standards set by clinical governance systems when interacting with Harry. There are key elements of clinical governance that were particularly useful in my practice.

To begin with, continuous pursuance of education and further trainings even after qualifying as a practitioner is emphasized by the institutions such as the NHS (2018). In this case, I viewed the case of Harry as a learning point. Furthermore, the continuing professional development of clinicians has been the responsibility of the governance systems and professionally, health practitioners have a duty to remain up-to-date with the information in the nursing care (WHO 2016).

Secondly, clinical governance is involved in ensuring clinical effectiveness which examines the extent by which a particular intervention works. In measuring the effectiveness of the clinical interventions, the nursing practitioners also consider other aspects such as the appropriateness of the intervention and the value for money (NHS 2018). In the case of Harry, while methotrexate medication was cheaper, it was clinically ineffective to manage the psoriasis condition the patient was going through. Therefore, I recommended, having evaluated the condition, that Harry be administered with adalimumab which is more clinically effective. In the current healthcare practice, the emerging evidence of effectiveness and safety considerations of medications ensures that due diligence is followed when prescribing medication to the patient.

Patient records are crucial in clinical practice and the governance institutions emphasizes on proper management of the records of the patients (demographic, Socioeconomic, Clinical information) through proper collection, and use of information within healthcare systems (WHO 2016). This helps to determine the effectiveness of the health system, track the statistic of the patients are grappling with and inform the healthcare provision decisions (Christopher 2001). I endeavoured to ensure that I document information about Harry in the course of the consultation. However, as good practice, I informed Harry beforehand of the record taking and keeping during the consultation and medication.

Cultural influence

Medical interactions are underpinned by cultural influence which dictates the unique behaviours that individual exhibit towards each other. My interaction with Harry was initially difficult to establish a rapport, partly due to concordance and partly due to his belief of refraining to interact with people due to his skin condition (Cribb, 2011). Upon the establishment of rapport, Harry was actively informed of the medication and the potential side effects. The interactions exhibit the aspect of cultural tolerance in healthcare where despite the differences in the beliefs of people, they manage to associate positively and look beyond the inhibiting factors (Cribb,2011). However, this has not always been the case since some of my patients have preferred paternalistic approach where they wanted me to make the choice for them (Coulter, 2008; Savage at el 2018).

The response of patients to medication is shaped by cultural beliefs and practices as well as aspects such as socialization experienced by the patients. Bearing this in mind, I understood why Harry was initially reserved when we engaged at the onset of consultation and this significantly would differ with other patients since there are different personalities, cultural beliefs and practices that are exhibited by people in their respective community settings.

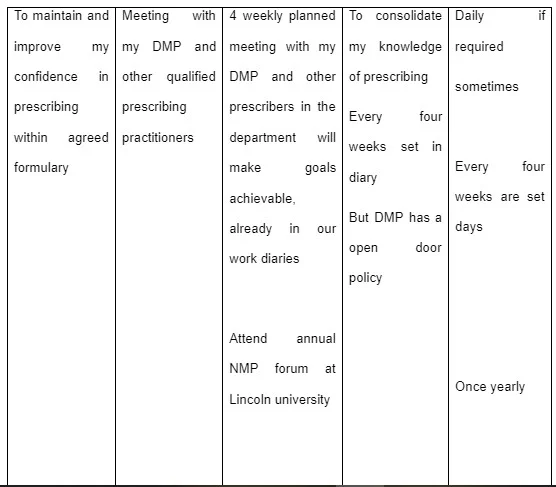

I am fully aware doing the NMP is only the beginning of my patient/ nursing journey and the realisation that a more holistic approach is required for my patient group is definitely required. This has made me think about the service I provided in past. I plan to carry out the audit over a 6-month period and discover what patients want from clinic appointments. This is part of my future personal development plan (Appendix B). It will be in a questionnaire format; this has been discussed with my DMP and clinical governance development team. The Identified patient group will be psoriasis patients only. The audit focus will be holistic assessment with free text boxes for any other relevant information they like to share. All findings will be shown and discussed at the clinical governance meeting attended by core members of the multidisciplinary team and a plan of care will be set up based on findings, in which standards will be set, the information collected and changes made will be revisited (Shaw,1980 1443-1445). The aim is to fundamentally improve patients care, experience and enhance their quality of life.

Commercial pharmaceutical companies influence.

The rise in the pharmaceutical companies and products have resulted in the intensification of the works of the pharmaceutical lobby groups who can be understood as representatives of pharmaceutical drug and biomedicine companies who engage in lobbying in favour of the pharmaceutical industry and its products (Brezis 2008). These lobby groups focus on a number of issues and marketing strategies that seek to ensure their products penetrate and gin dominance in the market. The intensity of the marketing activities is maimed at swaying the opinion of pharmacists and medical practitioners to use their pharmaceutical products

In this scenario the prescribing decision was achieved and governed by the Clinical Commission Group (2019) which monitors our high cost drugs, and provides the advisory to use adalimumab as first line. I am conscious of commercial influences such as pharmaceutical companies. I see numerous drug representative from high cost drugs companies trying to sway decision making within dermatology mainly with biological therapies and may try to offer bribes to health practitioners. The bribery Act (2012) regulates the health practitioners against behaviours such as taking briberies which will undoubtedly influence their decision making ability and create favouritism, an aspect that is against social justice and the principles of patient centred care (Lawrenson 2011). In fact, pharmaceutical companies are informed we like to be kept up to date with new treatments, but we follow the Nice Guidelines for Psoriasis, assessment and management (2017), and psoriasis pathways only. Lawrenson (2011) & McKinnon, (2007 65) state that prescribing decisions for personal gain should not happen, adding that such pharmaceutical companies plough billions into their research and development of medications therefore may steer one to use their products to gain a return on the investment.

Bearing in mind the fact that direct consumer marketing is also a possibility, the pharmaceutical companies are exhausting all the available options to ensure their products penetrate the market with online marketing efforts equally being put in place (Sufrin and Ross 2008). Thus, the clinical practitioners are confronted with too many options of medications for the same conditions with evident differences in the efficacy of the medications. With this information in mind, I ensured that the medication I selected for Harry was not influenced by the glamorous marketing statements of the products by based on the available evidence of its efficacy I treating psoriasis conditions. Additionally, I endeavoured to explain my choice of medication to Harry in order to ensure that he is not hoodwinked by the online memes of numerous pharmaceutical products claiming to treat the condition he is suffering from.

Conclusion

Reflecting on this, consultation was a very important part of my learning process (NMC 2019) (RPS 2016) and has enabled me to understand the importance of getting the right prescription choice for patients, it also highlighted that my current practice had flaws. I had not been assessing my patients holistically. Based on this discovery I plan to do an audit on current practice in the dermatology department. Clinical audit has been described as a core factor in clinical governance (Taylor and Lewis, 2011).

The saddest part of my role is it takes years for psoriasis patients to become eligible for biological therapy and I believe more time spent with patients would be beneficial as this gives the team more weight when making a prescribing decision, however this is unachievable goal due to the constraints of clinic time slots in an already over stretched service with in the NHS. I have been involved with patients on biological treatments since working in dermatology and on completing the NMP course will allow expansion to biological therapy service; it will give scope to improve the services as currently we do not have a dermatology prescribing nurse specialist in our trust.

Appendix A

My main role as a dermatology nurse is to assess patients in a nurse led clinic with dermatological conditions, medication monitoring and assessment of the medication prescribed and the effects. To manage side effects is a huge part of my job. I carryout regular patient review on a vast array of systemic treatments’ health conditions carry certain labels and such suggest that blames lie with the individual, and not the circumstances in which they live.

In Practice the medications used and prescribed are quite varied therefore completing the non-prescribing course will give me the foundations to build upon and under pin my knowledge further. The completion of the course will allow an increase in patients face to face time without the reliance of a doctors or consultant writing the prescription for my patients.

A twenty-two-year-old man called Harry attended a dermatology appointment that my DMP was assessing me as an observational practitioner as part of my NMP course. Harry had a follow up appointment that day, he been attending the dermatology clinic now for over 2 years on and off. On first meeting this patient it became apparent quite quickly that he was angry, agitated and frustrated with his skin condition. We have an electronic call system which my DMP prefer not to use, as she believes its good practise to collect your patients and walk down the corridor with them giving the opportunity to gain information from this simple act before the door is closed and the consultation starts, this I have adopted in my practice.

On this day I went to collect Harry he jumps up out of the chair and said finally, I apologised straight away and asked him how he was. By the time we started the consultation he was still angry with the world and everyone in it. My DMP introduced herself and I asked him to take a seat and I asked how we could help today, he refused to take a seat. It became apparent very quickly his skin was a huge source of upset and frustration and he expressed that his skin was affecting his every day activities, but his biggest concern was his work life balance, Harry had been given a written warning for time off work due to his severe uncontrolled psoriasis and he was angry. His skin condition was causing psychological issues along with physical pain and sleep deprivation. After some discussion it became even clearer due to financial problems, he could not afford to pay for the bus journey up to the hospital and his prescriptions charges and these were the reason why he was not attending his appointments.

His words that day included were, “I can struggle to express myself properly as a result of mixed anxiety and depression when talking face to face particularly when there are more people around or in a public place. I struggle to form relationships as a result of my skin condition and have had little success forming new relationships. My skin is off-putting and a source of anxiety and depression that has only built off that. When in public people often ask about my condition, which means it must be noticeable, further fuelling my anxiety. I try to hide my condition however using gloves and pockets is painful, therefore I preferable to stay in my room at home which effects my work as I just do not go. I live in shared accommodation and am often too scared to leave my room because of the anxiety I experience interacting with others in the house”. This really hit home to my DMP and myself that day.

He was currently taking oral Methotrexate (MTX) on and off bases, which is a folic acid antagonist and is classified as an antimetabolite cytotoxic agent that can be used for severe psoriasis. The use of oral methotrexate for non-malignant conditions require extra measure to ensure it not prescribed incorrectly. United Lincolnshire NHS (ULHT 2018) trust follow a strict policy, as it’s a once weekly dose the prescription must specify the dose and the actual day of the week it is taken on. Patient on oral MTX must be given MTX treatment booklet it should be filled in with all the relevant details as a way of ensuring the prescription matches what the clinician has prescribed, and pharmacy must check this before dispensing medication, this treatment was stopped and all the patient factors were considered that day and the decision was made that the on and off of medication was highly probably to treatment failure. The decision to stop the MTX with full discussion and agreement, Harry consented to a new treatment as he was a candidate for a biological therapy treatment.

Harry would now commence on a subcutaneous injection called adalimumab a high cost drug. Consideration was given to all the factors regarding Harrys situation to include prescription cost, workdays lost, his Dermatology quality of life index score 12 (DLQI), and his psoriasis index score greater than 10 (PASI) a requirement to start. Adalimumab works by reduces the effects of a substance called Tumour necrosis factor-alpha in the body that causes inflammation in the body. By blocking Tumour necrosis factor-alpha it is improving a patient skin who therefore stopping the suffering from psoriasis. Improving quality of life. To include a discussion on side effects/patient information leaflet with patient before consent is signed. Once patient established on treatment can be seen every 24 weeks, no prescription charge to Harry. All high cost drugs must go through the Clinical Commissioning Groups to gain the funding. Following the Prescribing Biological agents for psoriasis in ULHT (2016) patient has satisfied the criteria to be Eligible to start.

Appendix 2 My Personal development plan

Reference list

Augustin, M .and Krüger, M, Radtke, M. Schwippl, I. Reich, K. (2008) Disease severity, Quality of life and health care in plaque type psoriasis: A multicentre cross-sectional study in Germany. Dermatology;216(4):366–72.

Barber, P. and Robertson, D. (2009) Essentials of pharmacology for nurses. Maidenhead: university press.

Barea, A. and Reeken, S. (2018) An autonomous nurse-led psoriasis clinic to deliver patient-centred and research-focused care. Dermatological nursing, 17, (4) 28-32.

Beauchamp, T.L. and Childress, J. F. (2013) Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th edition. University Press: Oxford

Berlin, A. and Carter, F. (2007) Using the clinical consultation as a Learning opportunity. using the clinical consultation as a learning opportunity, Available from https://www.academia.edu/11961429/Using_the_clinical_consultation_as_a_learning_opportunity. [Accessed September 2019].

Bernheim S, Ross J, Krumbloz H, Bradley E. 2008. Influence of patient’s socioeconomic status on clinical management decisions: a qualitative study. Annals of family medicine, 6(1) 53-59

Bribery Act (2010) (C 9). Guidance to help commercial organisations understand the sorts of procedures they can put in place to prevent bribery. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/bribery-act-2010-guidance [ accessed on 09\06\2019].

Brezis M (2008). "Big pharma and health care: unsolvable conflict of interests between private enterprise and public health". Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 45 (2): 83–9, discussion 90–4. PMID 18982834.

Christopher’s, E. (2001) Psoriasis. epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clinical Expert Dermatology. 26:314–320

Courtenay, M. and Berry, D. (2007) Comparing nurses' and doctors' views of nurse prescribing: A questionnaire survey. Nurse Prescribing, (5) 205-2010

Coutlar, A. (1999) Paternalism or Partnership? British Medical Journal 319(7212)719_720

Cribb, A. (2011) Involvement, Shared Decision-Making and Medicines. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society Centre for Public Policy Research. King’s College London. Available from

Department of Health. (2006) Improving patients access to medicines. A guide to implementing nurse and pharmacist independent prescribing within the NHS in England. London; DOH.

Felzmann, H. (2012) Adherence, compliance, and concordance: an ethical perspective Nurse Prescribing, 10(8) 406-411

Fitzgerald, R. (2009) Medication errors. The importance of accurate drug history, British journal of clinical Pharmacology, 67, (6) 671-675.

Gill, C. and Murphy, M. (2014) Communication and Patient collaboration., H, Bradbury. and B, Strickland-Hodge. (eds) Practical Prescribing for Medical Students. Los Angeles, London, new Delhi, Singapore, Washington dc, Sage learning matters, 6-24.

Heath, G. and Bradbury, H. (2014) working with others. Bradbury, H and Strickland-Hodge (eds) Practical Prescribing for Medical Students. Los Angeles, London, new Delhi, Singapore, Washington dc, Sage learning matters, 58-59.

Jasper, M. (2013) Beginning Reflective Practice. 2nd edition. Cengage learning. Andover:

Joint Formulary committee (2018) British national formulary, volume 76, 888.

Joint Formulary Committee (2018) British National Formulary. Available from: http://www.medicinescomplete.com [Accessed on 23\09\2019]

Kaufman, G. (2008) patient assessment: effective consultation and history taking Nursing standard. 23(4)50-56

Lawrenson, V. (2011) Factors Influencing Prescribing. In D. Nuttal and J. Rutt-Howard (eds) the textbook of non-medical prescribing. Chichester; Wiley-Blackwell 95-199

McKinnon, J. (2013) The Case for concordance: Value and Application in Nursing practice, British Journal of Nursing, 22(13) 766-771.

McKinnon, J. (Editor,2007) Towards Prescribing Practice, The Application of ethical frameworks to prescribing John Wiley & Sons Ltd, England. 59-79.

McKinnon, J. (editor,2007) Towards Prescribing Practice, The Application of ethical frameworks to prescribing John Wiley & Sons Ltd, England. 36.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2012). Psoriasis: assessment and management. Clinical guideline {CG153} Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153/evidence/appendices-ag-pdf-188351536 {Accessed on 22\09\2018)

National institute of clinical excellence, Psoriasis: assessment and Management Clinical guideline [CG153] Published date: October 2012 Last updated: September 2017

Nice Guidelines National institute of clinical excellence guidelines psoriasis treatment (2019) Adalimumab for the treatment of adults with psoriasis. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153/evidence/appendices-ag-pdf-188351536 [Accessed on 26\09\2019]

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2015) The Code Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses and midwives. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council. Available from www.nmc.org.uk https://www.nmc.org.uk/news/press-releases/joint-statement-reflective-practice/ .[Accessed on 15\09\2019].

Policy for medicines Management (2018) Introduction Section, United Lincolnshire Hospital NHS Trust.

Roberts, D. (2013) Psychosocial nursing care: A guild to nursing the whole person. Maidenhead: Open University press. 25-27

Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (1997). From compliance to concordance. Achieving shared goals in medicine taking. London.

Savage, H. and Wheeler, T. (2018). Dermatology patients experience of information and support received when starting methotrexate. Dermatological nursing. 17 (4): 34-38.

Schon, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. London: Temple Smith.

Shaw, C (1980) Acceptability of audit British Medical Journal. 270 1443-1445

Stewart, D. and George, J. and Bond, C., Diack, L., McCaig, D., and Cunningham, S. (2009). Views of pharmacist prescribers, doctors and patients on pharmacist prescribing implementation. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 17 (2) 89-94.

Sufrin CB, Ross JS (September 2008). "Pharmaceutical industry marketing: understanding its impact on women's health". Obstet Gynecol Surv. 63 (9): 585–96. doi:10.1097/OGX.0b013e31817f1585.

Tagney, J. and Lewis, A. (2012) Clinical skills: history taking I cardiac patients. British journal of cardiac nursing. 7 (12) 588-594

Taylor, J. and Lewis, A. (2011) Enhancing Non-medical prescribing. In D. Nuttal and J. Rutt-Howards(eds) The textbook of non-medical prescribing. Chichester; Wiley-Blackwell 298-326

The psychological and social impact of skin disease on people’s lives (2013). A report of all-party parliamentary group on skin. London. https://www.appgs.co.uk/publication/view/the-psychological-and-social-impact-of-skin-diseases-on-peoples-lives-final-report-2013[ Accessed on 21\09\2019]

World Health Organization (2016) Global report on psoriasis. Available from http;//apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204417/1/9789241565189_eng.pdf. [Accessed 25\04\2019].

What Makes Us Unique

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts