Exploring Classroom Behavioral Challenges

Introduction

This literature review delves into the issue of classroom behavioral challenges to gain a deeper understanding of the existing research and debates that are relevant to behavioral management, providing essential education dissertation help. Through the literature review, the researcher hopes to build on their knowledge on classroom behavioral challenges. The literature review is divided into three main parts; the initial part, the introduction, the main body which is the literature review, and a conclusion. The introduction covers the nature of the focus area that is being reviewed, the basis through which the topic was selected, and the used definitions. The main body outlines the current research studies that have been located identifying the major questions asked in these selected articles, the studies methodologies, and the findings of the identified articles. From these findings, the researcher further locates themes enabling the drawing of general conclusions on classroom behavioral challenges, their triggers, and possible solutions to the challenges. The final conclusion provides a general summary of the findings around classroom behavioral challenges and classroom behavioral management. This literature review has a specific focus on learners with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADHD). Children with ADHD commonly portray defiant and aggressive behavior (Ramer et al. 2020). Some of the behavioral problems attributed to ADHD within classrooms include inability to focus, pay attention, and listen, restlessness, talking too much, fidgetiness, and disrupting classes (Graziano et al. 2020).

It is important that children with ADHD are identified early enough during their initial school going years and treated accordingly (Owens, 2020). De Pauw (2011) points out that ADHD symptoms have short term consequences and also lead to organizational impairments which include poor scores on report cards, class tests, and academic achievement tests. There are also short-term consequences of their problematic social interactions, and these include, less friends, conflicts in their family relations, and frequent rejection and neglect by their peers (Merrill et al. 2017). There is evidence that children with ADHD are at a higher risk of educational and interpersonal problems as they advance in age and that is evidenced by increased cases of placement in special education classes, failure in school, grade retention, early drop out, and juvenile delinquency. Cowell, Bellinger and Wright (2019), report that girls are particularly at a higher risk of suicide and self-harm.

Evidence points to children with ADHD as having a higher likelihood as compared to other kids to experience other different mental health problems. Sheenar-Golan et al. (2017), reported that children with ADHD were at a heightened risk of facing behavioral issues, learning differences, depression, anxiety, self-injury and substance abuse. Defiant and aggressive behaviors are recognized as the most common problems among children with ADHD (Bunford et al. 2015). This encompasses the refusal to follow directions from teachers and parents, more often than other children. These children commonly have emotional outbursts when they are required to complete tasks that they consider challenging or difficult. Webster-Stratton and Reid (2011), report that children with ADHD have tendencies of becoming defiant in particular situations, and showing disruptive behaviors. Such situations include being required to complete their homework, sit down, answer a question in class, stop playing a game, go to bed, and eat dinner. The deficits that are a part of ADHD make these situations difficult for the children with ADHD (Factor et al. 2016). The deficits include; being attentive, toleration of boring situations, transitioning from fun activities, reining in impulses, and control of their activity levels (Becker et al. 2012).

Children with ADHD experience a higher number of obstacles in their efforts to attain success as compared to the average students (Climie and Mastoras, 2015). ADHD has symptoms including the inabilities to be attentive, difficulty sitting still, and difficulties controlling impulses, which make it increasingly hard for children with the diagnosis to excel in school (Horowitz-Kraus, 2015; Ptacek et al. 2016). Pfinner and Haack (2014), posits that classroom behavior management comes in handy in meeting the needs of children with ADHD as it encourages the student to behave positively when in classrooms. That happens by way of a reward system or daily report cards, which go a long way in discouraging the affected children’s negative behaviors (DuPaul et al. 2011). It is worth noting that this is a teacher-led approach that has been proven to influence the behavior of students in ways that are constructive, increasing their engagement academically. When dealing with ADHD students, it is always important to keep in mind that these are individuals who have permanent neurological damage that increases the difficulty of changing their behaviors (Anderson et al. 2012). It is important to note that unique and individual interventions are the most suited for these students, than any other behavior programs (DuPaul and Langberg, 2015). Examples of effective interventions include the building of relations, adaptation of the environment, management of sensory stimulation, changing the used strategies in communication, provision of cues and prompts, adoption of a teach, review and reteach method, and the development of social skills. Classroom teachers, at all times, have to ensure that they accept all the students in their classrooms as they are. Some of the recommended teacher actions that have been proven to promote acceptance include; choice of learning materials that are representative of all student groups, ensuring the participants of all students in extra activities, recognition, valuing, respect and talking about differences, celebration of differences both cultural and ethnic, ensuring the design of learning activities for varying abilities, and modelling acceptance (Schuck et al. 2016).

Over the years, there has been increasing concern on problem behaviors in schools, and that is particularly the aggressive and extreme disruptive behaviors. While violent behaviors are the ones that capture the most attention of everyone, there are increased reports of disruptive behaviors including confrontations, swearing, inattention, and inappropriate clowning (Park and Lynch, 2014). Across the majority of schools challenging classroom behaviors are recognized as any such behaviors that either interfere with the safety of learning of other students, or interfere with the safety of members of staff in the school (Brokamp et al. 2019). Some of the common examples of challenging behaviors include, withdrawn behaviors, disruptive behaviors, violent or unsafe behaviors, and inappropriate social behaviors. Anxiety, staring, rocking, school phobia, social isolation, shyness, truancy and hand flapping are examples of withdrawn behaviors. Disruptive behaviors include calling out in class, throwing tantrums, refusing to follow instructions, screaming, swearing and being out of seat. All these different behaviors, affect the perpetrator`s learning and also have an effect on their other peers. This points to the importance of schools and all education stakeholders to have an accurate picture of the exact nature and prevalence of these behaviors as they interfere with learning, and additionally know about the triggers of these behaviors.

In depth exploration of the students who display challenging behaviors is quite important as the acquired information comes in handy in understanding the nature of the problem in addition to the required support services that these learners would need. It is rather unfair for the disruptive behaviors of one student to affect the learning of others and this is why these behaviors have to be controlled.

For a fact, problem behaviors are among the most pressing issues in today`s classrooms. In addition to interfering with the student`s learning potential of the student exhibiting the behavior, problem behaviors also have rippling effects on larger learning environments. Owing to the fact that problem behaviors are disruptive of learning environments, teachers have to adopt pro-active behavior management strategies that have been found to be effective. With the important role that teachers play, it has however been reported that the majority of pre-service teachers are not adequately trained and educated such that they are well prepared to manage problem student behaviors effectively. This study specifically focuses on pre-service teachers. Most of the education that pre-service teacher students receive is reported to be largely theoretical, not empirically based, and is inadequate for addressing the different situations that teachers would likely face within classrooms. The present study defines pre-service teachers as education majors who are not yet teaching on a regular basis. The purpose of the present study is to determine the confidence of pre-service teachers in the use of classroom-based management strategies for purposes of supporting students who have behavioral challenges and ADHD. This study further reviews the extent of positive student behavior and academic outcomes.

Identified studies

Classroom management

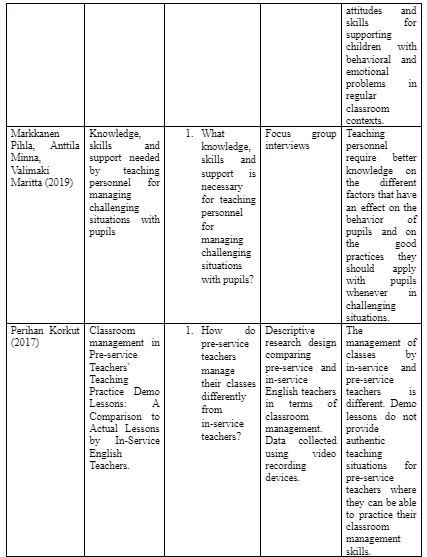

One of the themes that repeatedly emerges from the identified studies is that pre-service teachers manage their classes differently from other teachers, for instance, in-service teachers (Korkut, 2017; Strelow et al. 2020). Control of task progress by pre-service teachers is not as frequent and they do not deal with audibility as frequently, and their use of voice and language adjustments is also minimal. McMahon (2012), points out that this could be a result of the fact that they have students who are relatively more obedient and not as disruptive and this is as a result of the existence of the presence of a mentor in the classrooms during the demo classes. There is also the possibility of the students perceiving the pre-service teachers as guests and therefore putting efforts to please them. For example, in Pihla et al. (2019), an observation was made that the frequency of asking permission from the teachers was low. Therefore, the demo lesson experiences do not provide the teachers with truly authentic teaching situations whereby they can effectively practice the different classroom management skills. Kristina et al. (2017), however, found no significant intervention-related differences in preservice teachers, in terms of self-efficacy, endorsement of control and rules, support and warmth and negative beliefs. The study, however, found preservice training to have the potential of effectively affecting teacher’s immediate attitudes and skills for purposes of supporting children who exhibited behavioral and emotional problems in regular classroom contexts.

Training

In the different included studies, training is commonly mentioned as one of the important factors that has an influence on the courage of pre-service teachers to utilize classroom management strategies (Kristina et al. 2019; Markannen et al. 2019; Latouche and Gascoigne, 2019). Training is therefore, the second theme. Latouche and Gascoigne (2019), report that training has an indirect association with, and additionally mediates through perceived effectiveness and shows a direct effect on the adoption of classroom management strategies. The training equips teachers with the necessary knowledge about ADHD and classroom management strategies (Poznanski et al. 2018). It is worth noting that the present study operationalizes training as either formal or informal in-service training on ADHD. An observation is made that ADHD training does not always lead to the transfer of knowledge and this suggests the possibility of these two constructs being incomparable. Pre-service teachers are not as knowledgeable as in-service teachers, even though pre-service teachers are reported as holding increasingly general ADHD knowledge, that information on prevalence, etiology, and diagnostics (Anderson et al. 2012). Those teachers who gain their knowledge through in service training notably focus more on the different methods of intervention (Lee et al. 2019).

Direct experiences

From some of the included studies, there is evidence that the individual stress that pre-service teachers have and expectation of experiencing whenever they go about teaching ADHD students plays a relatively important role in informing their intentions of using classroom management strategies that lack effectiveness (Pihla et al. 2017; Klopfer et al. 2017; Latouche and Gascoigne, 2019). The implication of this finding is that the intentions to use ineffective CMS among pre-service teachers comes about from higher stress from students who have ADHD. An inverted U-function is followed during performance under stress, translating to performance continuously increasing until a stress-peak is reached, and then a decline in performance follows (Strelow et al. 2021).

Expectations and attitudes

Behavioral attitudes emerge as another theme (Klopfer et al. 2017; Strelow et al. 2017). These attitudes towards the use of CMS are an important factor in influencing the courage of pre-service teachers to utilize ineffective and effective CMS. When there are expectations that the adoption of a certain behavior will bring about consequences that are effective, the intentions of performing the behavior go up. The implication of this is that pre-service teachers have heightened confidence of using CMS as long as there are expectations placed on them of being effective, and that is regardless of whether they are actually effective or not. Therefore, it is increasingly important to believe in the effectiveness of classroom-based management strategies, other than just simply knowing about them (Shillingford and Karlin, 2014).

Additionally, the held attitudes about effective CMS are influenced by the attitudes of pre-service teachers towards ADHD students (Ajuwon et al. 2012). From the included studies, there does not exist any similar effect for ineffective CMS. The implication of this is that when a pre-service teacher has a more positive attitude towards students with ADHD, it becomes increasingly easier for the teachers to believe that CMS will be effective, and the stronger the teachers intentions of using them (Zambo et al. 2013). There are reports from different studies that teachers are more stressed about and have increasingly critical attitudes about students who have ADHD. This therefore, points to the need for improving the attitudes of pre-service teachers towards students who have ADHD and that is because that goes a long way in opening a mental door that facilitates the effective use of CMS.

Individual differences

Individual differences emerge as another theme (Korkut, 2017; Latouche and Gascoigne, 2019; Chitiyo et al. 2020). There is immense stress and dissatisfaction experienced by teachers and this leads to the increased prevalence of mood disorders. Understanding why higher psychological strain leads to a decline in the held attitudes towards effective CMS is quite easy. When one is stress, they become less engaged in their day to day tasks, and their held attitudes towards their job roles also deteriorate (Shillingford and Karlin, 2014). When the psychological strain is paired with students who are disruptive, pre-service teachers are presented with rather difficult tasks, which reduces their likelihood of adopting effective classroom management strategies (Barned et al. 2011). The relevance of perceived behavioral control is only in negatively influencing the intentions of using ineffective CMS and therefore plays the role of a preventive function. Perceived control does not increase the use of effective CMS while the higher the perceptions of control, the less the intentions to use lowly effective and possibly harmful CMS. In addition, pre-service teachers are not as experienced about working in schools, and therefore, do not know too much about the possibilities of using CMS. However, in the event they feel they can teach students with ADHD effectively, they show little willingness of using ineffective CMS (Whitley et al. 2016).

The intentions of using effective CMS are increased by knowledge, in addition to the improvement of the attitudes of using the strategies, while at the same time, reducing the intentions of using ineffective CMS and the held attitudes towards the strategies. Knowledge’s influence is observed to be consistent with the findings of other studies held in the past. It is worth noting that the effects on attitudes towards CMS are way higher as compared to the intentions of using them. The necessary precondition appears to be a knowledge-minimum, even though knowledge by itself is not adequate for changing an individual’s intentions. It is only agreeableness that is found to have an effect on the intentions of using effective CMS. In relation to intention of using ineffective CMS, there is no personality variable that is found to have an influence. These findings are supported by the findings of other previous studies that found personality to have the effect of changing the attitudes but not the intentions to execute the behavior in question. Rodriguez et al. (2018), argue that agreeableness brings about altruistic and cooperative behavior and is able to help explain why there are pre-service teachers who still have intentions of using effective CMS even with the challenges (Stephenson, 2018). A relevant effect on influencing attitudes towards CMS is also shown by psychological strain. This negatively affects the attitudes towards effective CMS.

Conclusions

From this literature review, it can be concluded that pre-service teachers are not as confident when it comes to the use of classroom-based management strategies for supporting students who have behavioral challenges and ADHD. While they have gone through the prerequisite learning, they have not been in real classroom environments on their own and therefore likely face challenges when they find themselves alone with students with challenging behaviors and ADHD. These teachers therefore, stand to benefit from exposure training that puts them in truly authentic teaching situations as that would go a long way in boosting their confidence of adopting classroom management strategies. Classroom management strategies are found to be effective in the establishment and further sustenance of orderly environments within classrooms, facilitates increasingly meaningful academic learning, and reduce negative behaviors while increasing the time learners spent when academically engaged. These strategies should therefore be embraced in all classrooms.

Continue your exploration of Exploring Brain-Based Strategies in Education with our related content.

References

Ajuwon, P.M., Lechtenberger, D., Griffin-Shirley, N., Sokolosky, S., Zhou, L. and Mullins, F.E., 2012. General Education Pre-Service Teachers Perceptions of Including Students with Disabilities in Their Classrooms. International Journal of Special Education, 27(3), pp.100-107.

Anderson, D.L., Watt, S.E., Noble, W. and Shanley, D.C., 2012. Knowledge of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and attitudes toward teaching children with ADHD: The role of teaching experience. Psychology in the Schools, 49(6), pp.511-525.

Anderson, D.L., Watt, S.E., Noble, W. and Shanley, D.C., 2012. Knowledge of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and attitudes toward teaching children with ADHD: The role of teaching experience. Psychology in the Schools, 49(6), pp.511-525.

Becker, S.P., Luebbe, A.M., Stoppelbein, L., Greening, L. and Fite, P.J., 2012. Aggression among children with ADHD, anxiety, or co-occurring symptoms: Competing exacerbation and attenuation hypotheses. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 40(4), pp.527-542.

Becker, S.P., McBurnett, K., Hinshaw, S.P. and Pfiffner, L.J., 2013. Negative social preference in relation to internalizing symptoms among children with ADHD predominantly inattentive type: Girls fare worse than boys. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(6), pp.784-795.

Brokamp, S.K., Houtveen, A.A. and van de Grift, W.J., 2019. The relationship among students' reading performance, their classroom behavior, and teacher skills. The Journal of Educational Research, 112(1), pp.1-11.

Bunford, N., Evans, S.W. and Wymbs, F., 2015. ADHD and emotion dysregulation among children and adolescents. Clinical child and family psychology review, 18(3), pp.185-217.

Chitiyo, J., Chitiyo, A. and Dombek, D., 2020. Pre-service teachers' understanding of problem behavior. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 12(2), pp.63-74.

Dunne, L. and Moore, A., 2011. From boy to man: a personal story of ADHD. Emotional and behavioural difficulties, 16(4), pp.351-364.

DuPaul, G.J., Weyandt, L.L. and Janusis, G.M., 2011. ADHD in the classroom: Effective intervention strategies. Theory into practice, 50(1), pp.35-42.

Elik, N., Wiener, J. and Corkum, P., 2010. Pre‐service teachers’ open‐minded thinking dispositions, readiness to learn, and attitudes about learning and behavioural difficulties in students. European Journal of Teacher Education, 33(2), pp.127-146.

Graziano, P.A., Garcia, A.M. and Landis, T.D., 2020. To fidget or not to fidget, that is the question: A systematic classroom evaluation of fidget spinners among young children with ADHD. Journal of attention disorders, 24(1), pp.163-171.

Horowitz-Kraus, T., 2015. Differential effect of cognitive training on executive functions and reading abilities in children with ADHD and in children with ADHD comorbid with reading difficulties. Journal of attention disorders, 19(6), pp.515-526.

Klopfer, K.M., Scott, K., Jenkins, J. and Ducharme, J., 2019. Effect of preservice classroom management training on attitudes and skills for teaching children with emotional and behavioral problems: A randomized control trial. Teacher Education and Special Education, 42(1), pp.49-66.

Korkut, P., 2017. Classroom Management in Pre-Service Teachers' Teaching Practice Demo Lessons: A Comparison to Actual Lessons by In-Service English Teachers. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 5(4), pp.1-17.

Latouche, A.P. and Gascoigne, M., 2019. In-service training for increasing teachers’ ADHD knowledge and self-efficacy. Journal of attention disorders, 23(3), pp.270-281.

Lee, K.W., Cheung, R.Y. and Chen, M., 2019. Preservice teachers’ self‐efficacy in managing students with symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: The roles of diagnostic label and students’ gender. Psychology in the Schools, 56(4), pp.595-607.

Markkanen, P., Anttila, M. and Välimäki, M., 2019. Knowledge, skills, and support needed by teaching personnel for managing challenging situations with pupils. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(19), p.3646.

McMahon, S.E., 2012. Doctors diagnose, teachers label: The unexpected in pre-service teachers’ talk about labelling children with ADHD. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(3), pp.249-264.

Owens, E.B., Hinshaw, S.P., McBurnett, K. and Pfiffner, L., 2018. Predictors of response to behavioral treatments among children with ADHD-inattentive type. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(sup1), pp.S219-S232.

Park, H.S.L. and Lynch, S.A., 2014. Evidence-based practices for addressing classroom behavior problems. Young Exceptional Children, 17(3), pp.33-47.

Pfiffner, L.J. and Haack, L.M., 2014. Behavior management for school-aged children with ADHD. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 23(4), pp.731-746.

Poznanski, B., Hart, K.C. and Cramer, E., 2018. Are teachers ready? Preservice teacher knowledge of classroom management and ADHD. School Mental Health, 10(3), pp.301-313.

Ptacek, R., Stefano, G.B., Weissenberger, S., Akotia, D., Raboch, J., Papezova, H., Domkarova, L., Stepankova, T. and Goetz, M., 2016. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and disordered eating behaviors: links, risks, and challenges faced. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment.

Ramer, J.D., Santiago-Rodríguez, M.E., Davis, C.L., Marquez, D.X., Frazier, S.L. and Bustamante, E.E., 2020. Exercise and academic performance among children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and disruptive behavior disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatric exercise science, 32(3), pp.140-149.

Rodriguez, K.F.R. and Abocejo, F.T., 2018. Competence vis-à-vis performance of special education pre-service teachers. European Academic Research, 6(7), pp.3474-3498.

Schuck, S., Emmerson, N., Ziv, H., Collins, P., Arastoo, S., Warschauer, M., Crinella, F. and Lakes, K., 2016. Designing an iPad app to monitor and improve classroom behavior for children with ADHD: iSelfControl feasibility and pilot studies. PloS one, 11(10), p.e0164229.

Shillingford, S. and Karlin, N., 2014. Preservice teachers’ self efficacy and knowledge of emotional and behavioural disorders. Emotional and behavioural difficulties, 19(2), pp.176-194.

Stephenson, J., 2018. A Systematic Review of the Research on the Knowledge and Skills of Australian Preservice Teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), pp.121-135.

Strelow, A.E., Dort, M., Schwinger, M. and Christiansen, H., 2021. Influences on Teachers’ Intention to Apply Classroom Management Strategies for Students with ADHD: A Model Analysis. Sustainability, 13(5), p.2558.

Strelow, A.E., Dort, M., Schwinger, M. and Christiansen, H., 2020. Influences on pre-service teachers’ intention to use classroom management strategies for students with ADHD: A model analysis. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, p.101627.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M.J. and Beauchaine, T.P., 2013. One-year follow-up of combined parent and child intervention for young children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(2), pp.251-261.

Whitley, J. and Gooderham, S., 2016. Exploring mental health literacy among pre-service teachers. Exceptionality Education International, 26(2).

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts