Existence of Venture Capitalist

Introduction

A venture capitalist (VC) is a private equity investor who contributes to a company’s high growth potential by assisting them in financial assets. Those companies that are helped by venture capitalists are generally start-ups, early growing entities or small companies that wish to expand (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018). When investing in such entities, venture capitalists take high-risk decisions for the sake of making substantial amount of returns. Looking into some of the largest American companies such as Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Dell, one notices that that the majority of them were backed up by a venture capital fund during their initiation stages. One may wonder what the extent of the success of these companies would be without the VC financing. If in case you are seeking business dissertation help, understanding the role of venture capitalists along with their impact on the growth trajectory of companies is a very vital aspect to explore. Conversely, what is the fundamental role of these venture capitalists in the large business environment, and how exactly do they affect entrepreneurial finance?

Firstly, this essay will explore the role assumed by VCs, and ways in which it intervenes the financial cycle and entire business structure. This section will also serve to analyse the different funds structure responses too different financial needs. The supply of venture capital generates considerable value to economy through entrepreneurship and innovation.

Entrepreneurship and VCs

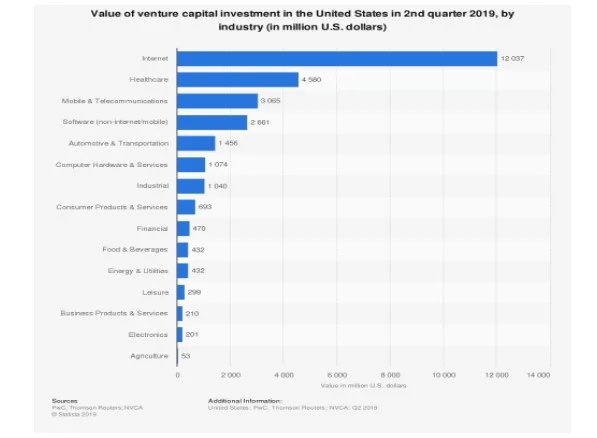

Fundamentally, entrepreneurship in VC backed firms is stimulated by the creation of new firms, which in turn, generates employment. In study conducted by Strebulaev (2015) found that in 2013 alone the venture capital industry in the US generated four million. In addition, innovation is also stimulated through the funding in niche sectors such as technology, healthcare, or Biotechnology. According to the statistics by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and Thomson Reuters (2019), among the industries that have benefited hugely from the venture capital investment are internet-based businesses (e-business), healthcare, mobile & telecommunication, and software respectively. Essentially, through the venture, the unproven business ideas and entities can be launched as well allowing invention, innovation, and room for product develop through the pressure of breakeven before maturity.

Figure 1: Venture Capital Investment in the US (PwC and Thomson Reuters , 2019) The findings, as shown by figure 1, indicate venture capital investments represent approximately 12 billion U.S. dollars on the internet industry in the United States. In addition, it encourages incentive towards research and development (R&D) which represents positive externalities from an economic perspective. In such, the venture capitalists enhance employment as well research and development, which is highly beneficial for the economy by boosting it. As argued by Bocken (2015), the capital as a form of further growth of wealth is fundamental in developing economy. Entrepreneur tapping into this approach to reproduce wealth is arguably a lifeblood particularly to the new industries, becoming a source of equity for start-ups businesses. According to Ferrary & Granovetter (2009) and Wonglimpiyarat (2016), the capital venture had a huge role acting as a catalyst to economic growth in such areas as Silicon Valley, in the USA, and Zhong Guan Cun in China synonymous with successful technology-oriented businesses and start-ups.

Capital Venture Timeframe

The venture developments take three stages. The first, is at the very first financing source called ‘the bootstrapping’ usually comes from the family, friends and fools of the founders as well as public sponsorship (Jayawarna et al., 2015; Cornwall et al., 2015). However, as lamented by Alemany and Andreoli (2018), some venture capitalist can get interested at this stage but under the condition that to have conducted a keen analysis and gathered enough information. Patel et al. (2011) and Vilajosana et al. (2013) illustrated that in a business world driven instant gratification, entrepreneur should structure both their strategy and business model in a manner that is worth financing. As such, through holding out, it aids the entrepreneurship to put up approaches and thought-out structures in wait for financing in a way that it enables use of investment to scaling up rather than figuring out business model and what its supposed to do.

Start-ups stage is the second step modelled as a moment for venture capitalists to intervene. At this point, the company is already selling its products or service and sometimes already has a few first customers. However, at this stage, according to Ley & Weaven (2011) and Colombo & Grilli (2010), inception of business ideas and manifesting into successful business venture requires investment in terms of financially and human labour as well as cautioning entrepreneurs from risks demand a proper guide, informed network and decisions, and insight into given industry. At initiation/inception stage, the business idea is not capable to cover its expenses yet and in these cases, large amounts of money are needed, and for that, a venture capital fund will be the most likely option of financing.

The third stage of venture development is at the growth stage, the business strives to succeed to be profitable, and therefore working towards meeting credit control requirement, post returns in investment, and gain market base. However, the stage is rooted on the success of the first and second stages backed by growth machinery, sales skeleton, deployment, and support team. Manigart & Sapienza (2017) and Maxwell et al. (2011) illustrates that growth stage embodies generating consistent source of income, business-to-business relationship, taking new consumers, and enhancing employees’ engagement driven by founding business objectives and goals. Nevertheless, Ramaraju et al. (2017) argued that at this stage, business have to divide its time between satisfying consumers and employees, products/service quality, social responsibilities, retaining talented employees, and, importantly, dealing with competition.

According to Barry and Mihov (2015), after these three stages of development, banks, as an investor, holds talks with the business on ways the two can collaborate financially. After the growth stage, maturity stage encompasses the company making large investment since the focus is to sustain its current market share. Hence, venture capitalists will never intervene during the maturity stage except in the case of entrepreneurship by acquisition (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018).

Forms of venture capital fund structures and financial models

VC can takes different forms. Fundamentally, various funds have distinct organisational shape and legal structures. According to Litvak (2009) and Gassman (2016), VC limited partnerships are the most popular model of venture capitals and consist in an alliance between the general partner and the limited partners (LPs) who are the investors. The source of revenue from the venture capitalists perspective is separated in two categories; a management fee and a remuneration. According to Groh & von Liechtenstein (2011) and Litvak (2009), the management fee is a settled payment per period to cover the salaries of the investment team. During the investment period, it is calculated with percentage ranging from 1.5 % to 2.5% of the total commitments involved. Then, to encourage the team and in particular the fund manager, a remuneration called ‘carried interest’ is given, which is a percentage given of the returns of the funds. This, on a basis of the fund manager receiving 20% and the LPs the remaining 80% (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018).

However, it is to be noted that the manager of the funds is not entitled to the carried interest until the return's goal is given to the investors. As such, compared to the corporate fund, it can be argued that LP have quite similar missions and are gathered by same nature of professional. They, however, as pointed out by (REF), differ in their organization and incentive structures and the two proceed in different ways when sponsoring other firms to creating in-house venture capital activities or when launching accelerated projects of young businesses mentorship (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018). Corporate fund are wild spread in the US, for instance Google ventures has invested in more than one hundred highly innovative business related to phones, video games, energy and life sciences (Gassman, 2016). In essence, their core activity is not investing in start-ups for the sake of share returns such as in limited partnership funds but more about a strategic intensive related to business development or innovation input (REF).

At a later stage, goals of corporation are to venturing into acquisition of these start-ups, supported through capital venture system. Extending the past example, Google ventures strategically strives to incorporate successful funded companies into the Google brand (Gassman, 2016). However, studies have found that venture capitalism are less successful than Limited Partnership because of its lack of strategic focus resulting from short run funding needs (REF). These discontinuities imply shorter lived and fewer stable funding which impacts its overall efficacy (Gassman, 2016).

Information asymmetry: Entrepreneurs and Venture capitalist

Essentially, in a market of imperfect information, venture capitalist plays a role of principal intermediary between the entrepreneurs and the ultimate holder of capital. Asymmetries in information tend do arise more strenuously in entrepreneurial finance than in established firms (Stromberg, 2001; Cuñat, and Garcia-Appendini, 2012). First, according to Klapper & Love (2011) and Yung (2009), it occurs when the investors have access to less information than the entrepreneurs do. For instance, it is challenging for outside investors such as pension funds to recognise the potential value and keen features of technological innovation as compared to the entrepreneurs with direct and reliable information. As highlighted by Chan (1983), this leads to what is referred to as ‘hidden information’. In this context, venture capitalists will positively act as agents to remedy this imperfect information. Since venture capitalists have the knowledge and expertise of the sector, they act as the informed agent by advising investors with strategic guidance and by increasing their welfare (Chan, 1983; Häussler et al., 2012; Rider, 2009).

Moreover, there are also ethical concerns founded on the fear that entrepreneurs have the incentive to act in their personal interest (Dimov, 2010; Carsrud, and Brännback, 2011). Masulis and Nahata (2011) contended that this could happen after entrepreneurs receive the financing from the limited partners and decide to channel the funds to areas or projects that would only beneficial to them. An example would be an entrepreneurial scientist that directs the finances and assets towards own research in order to get recognition rather than generating financial return for the investor (Chan, 1983). As pointed by Masulis and Nahata (2011), such conflicts of interest between the ultimate holder of capital and the entrepreneurs can be minimised by the financial intermediation provided by VCs in one of two ways. First, though structuring financial contracts. For instance, by a distribution of cash flow and controlling rights between investors and entrepreneurs. Secondly, as highlighted by Stromberg (2001), through the collection of information by selecting the qualified entrepreneurs and screening the consistency of all ideas. Klausner & Litvak (2017) and Park & Tzabbar (2016) contends that such approach results in entrepreneurs centring and putting the interest of the business entity and investors first. It is worth noting that venture capitalists act as an intermediary by giving not only financial support, also, strategic advices and guidance.

Role of Venture Capitalists in Building Companies

Venture capitalist involvement in businesses is analysed from three entrepreneurial perspectives; decision-making, goals, and strategy formulated. First, Choi and Gray (2008) lauds that venture capitalists involvement in the company implies that entrepreneurs have less control and ownership towards their own business. As argued by Caselli et al. (2009), this could lead to unbalanced allocation of power that in turn leads to conflicts and instabilities, which negatively influence the two parties’ behaviours. Those conflicts also have negative impact on partners’ relations due to fractured trusts. Furthermore, according to a study from Higashide and Piney (2002), involved parties would have divergent reasons of start-ups failure. Yang et al. (2009) highlighted that while the entrepreneurs find issues in the market itself, the CVs spot gaps in the managerial actions. One can argue that such view can have fundamental influence on the decision-making process of a business.

On the other hand, it can be argued that those conflicts can improve decisions making. First, because it encourages the two parties to challenge each other’s point of view as well as jointly find innovative solutions hence challenging conventional perspective and moulding innovative problem solving (Zacharakis, 2010). Moreover, building from Kirsch et al. (2009) assertion, accommodating different views in decision-making process leads to enhancement of creativity and innovativeness.

Secondly, from a goal perspective, it can be argued that entrepreneurs tend to be more attached to their businesses while venture capitalists’ aims are more monetarily oriented. In addition, Dimov (2010) and Collewaert (2012) found that entrepreneurs could feel threatened by venture capitals input. However, studies demonstrate that entrepreneurs and VCs have common goals, namely; growth, performance, and efficacy (Hmieleski, and Carr, 2008; Stam et al., 2014). Finally, even the disparities between entrepreneurs and VCs can be seen as beneficial as they enhance the complexity criterion by sharing information and learning from each other with the final aim to be on the same page in term of objectives.

Lastly, in term of strategy, it is notable that venture capitalists represent a real comparative advantage in comparison to other type of investors founded on three elements. First, based on the views held by Berger and Schaeck (2011) are driven by their expertise in the sector and guidance during the all process. Secondly, their networking resources and connexions Keil et al. (2010). Thirdly, they sometimes have useful marketing information based on experiences. In summation, even if there are some disadvantages of venture capitalists input to growing firm, venture capitalists are still a great competitive advantage for entrepreneurs as it allows them to reach fast and efficient business growth.

Alternative funding to venture capital

Business angels can be defined as high profile individuals who invest their personal money, experience, and time in an unquoted firm with the aim of financial gain. Usually, as pointed by Alemany and Andreoli (2018), they invest in new starting companies as do venture capitalists. According to Politis (2008) and Parhankangas and Ehrlich (2014), two important elements that characterise a business angel profile are, one, their ability to make their own investment decisions and, secondly, the fact that they invest their own money. In comparison to investment choice made by regrouped investment structure such a venture capitalist, business angels do not have an obligation to invest if they do not find suitable projects (Clark, 2008; Harrison et al., 2010). Furthermore, business angels are efficient in making decisions regarding investment since they do not need to justify their decisions to anybody.

Moreover, Wallnöfer & Hacklin (2013) and Tomczak & Brem (2013) argues that investment model followed by business angel is highly to focus on the support they will offer to their investees. According to Capizzi (2015), they tend to supervise and mentor the board in addition to teaching all kinds of valuable resources and inputs such as social skills and intuition. As elaborated by Festel and De Cleyn (2013), in addition to this gain of information, it allows reducing the occurrence of asymmetric information leading to taking of less risk. Ivashina (2009) contended that involvement is a significant motive that tends to be more focus on the experience gain rather than the financial gain. In comparison with venture capitalists, the benefit of business angels to the business is quite variable and tends to be considered as a low profitable investment (Batabyal 2012). This confirms the assumption that some business angels are more motivated by the enjoyable benefit of the activity rather than the monetary aim.

In addition, Belleflamme et al. (2014) defined crowdfunding by a recent alternative model of financing that puts in contact individual and entities who can lend, give, or invest money directly with those who need financing for a particular project. The first main characteristic of crowdfunding is the ability of a business concept to be financed many individuals and companies brought by together common objective. Recently, social media era has taken a central role in brings these individuals and companies together, usually email or newspapers plays a role (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018). According to Belleflamme et al. (2014), what differentiates crowdfunding from the other types of funding is its close relation to its market audience. Schwienbacher and Larralde (2010) highlights that by exposing its presence at a very early stage to a large number of individuals and business entities, crowdfunding utilises the usual model of markets settled selection. Comparing this to venture capital, the entrepreneurs will target the optimal investor to pitch their project (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018; Mollick, 2013). However, crowdfunding has some disadvantages for entrepreneurs and investors. First, Manchanda and Muralidharan (2014) purports that, usually, the ideas are not unique but shared exposing the business concept to being copied by competitors. Additionally, it has a risk of getting a low reputation in case it does achieve target funds. Secondly, in case it fails to get target funds, any finance pledged is usually returned to the investors and the business will receive nothing. Therefore, the goal set needs to be reachable (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018; Wash, 2013).

In an industry facing constant evolution, the patterns of entrepreneurial finance have deeply changed due to key drivers. Keil et al. (2008) and Bocken (2015) contends that the impact of technology, the role of CEOs, and regulations has demonstrated ways in which VC evolves in a perpetual changing industry. First, financial technology highly influences the current VC industry by generating new financial transaction activities, which encourage the development of new ventures gathered by qualified VCs. For instance, by investing in niche sectors such as transferwise. However, such innovations encourage the emergence of Blockchain technology highlighting that entities transact increasingly in a direct manner rather than toward an intermediaries like venture capitalist (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018).

Additionally, according to Hoffman (2018), an internal claim emphasises how motivated and ambitious CEOs build large financial product companies by themselves and therefore become CEOs and Venture capitalists at the same time. For instance, Sam Altman, the CEO of Ycombinator, which is a dominant accelerator that invests twice a year in a large number of companies, is both a CEO and a venture capitalist. Therefore, the distance between CEO and venture capitalists tend to diminish creating a model for venture capitalists who are interested in creating businesses rather than just being involved in investing in them. Lastly, Alhorr et al. (2008) contends that looking at today’s main actors in regulation among the venture capitalists, is the European Constitution (EC), which tries to reduce tariffs and remove tariff barriers affecting the venture capital market by enabling global trading.

An example of this kind of law gathered by the EC is the ‘European venture capital funds (EuVeca) regulation’ (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018). These kind of regulations promote entrepreneurship, improve access to new markets through internationalisation, and provide support networks and information for the SME. In the future, since UK is planning to leave the EU, a change in the law and ability to free trade might strongly affect the venture capitals activities across Europe. As such, one can argue that venture capitalists run the risk of being solicited depending on free trade financial market (Alemany and Andreoli, 2018; Caselli, and Negri, 2018). Moreover, although financial technology and VCs getting closer to the role of CEO are key drivers for VC’s evolution, they will remain and be used as a principal form of funding.

Conclusion

Throughout this essay, it has explored ways in which VCs are a factor of economic growth, innovation and entrepreneurship, and how they intervene at key moment of the growing venture according to the needs of the company trough period. Secondly, while information asymmetric can be source of issues between the LPs and entrepreneurs, VCs are great financial and strategic intermediate. In addition, VC involvement in the business can raise some tensions due to power unbalanced or conflict of interest. However, it can be argued, VCs are still offer competitive advantage for the companies, compared to other kinds of investors. Then, key features of other alternative form of funding such as business angel and crowdfunding were explored. Lastly, it looked into the VC changing industry and new challenges demonstrating that VC funding is still highly important on the venture market.

References

Alemany, L. and Andreoli, J. (2018). Entrepreneurial finance.

Alhorr, H.S., Moore, C.B. and Payne, G.T., 2008. The impact of economic integration on cross–border venture capital investments: Evidence from the European Union. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(5), pp.897-917.

Amit, R., Brander, J. and Zott, C. (1998). Why do venture capital firms exist? theory and canadian evidence. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(6), pp.441-466.

Barry, C.B. and Mihov, V.T., 2015. Debt financing, venture capital, and the performance of initial public offerings. Journal of Banking & Finance, 58, pp.144-165.

Batabyal, A.A., 2012. Project financing, entrepreneurial activity, and investment in the presence of asymmetric information. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 23(1), pp.115-122.

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T. and Schwienbacher, A., 2014. Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. Journal of business venturing, 29(5), pp.585-609.

Ben, M. (2019). Role of Venture Capital in the Economic Growth of United States. [online] Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@abc_40376/role-of-venture-capital-in-the-economic-growth-of-united-states-11b2090330a1 [Accessed 22 Nov. 2019].

Berger, A.N. and Schaeck, K., 2011. Small and medium‐sized enterprises, bank relationship strength, and the use of venture capital. Journal of Money, Credit and banking, 43(2‐3), pp.461-490.

Bocken, N.M., 2015. Sustainable venture capital–catalyst for sustainable start-up success?. Journal of Cleaner Production, 108, pp.647-658.

Capizzi, V., 2015. The returns of business angel investments and their major determinants. Venture Capital, 17(4), pp.271-298.

Carsrud, A. and Brännback, M., 2011. Entrepreneurial motivations: what do we still need to know?. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), pp.9-26.

Caselli, S. and Negri, G., 2018. Private equity and venture capital in Europe: markets, techniques, and deals. Academic Press.

Caselli, S., Gatti, S. and Perrini, F., 2009. Are venture capitalists a catalyst for innovation?. European Financial Management, 15(1), pp.92-111.

Chan, Y. (1983). On the Positive Role of Financial Intermediation in Allocation of Venture Capital in a Market with Imperfect Information. The Journal of Finance, 38(5), p.1543.

Choi, D.Y. and Gray, E.R., 2008. Socially responsible entrepreneurs: What do they do to create and build their companies?. Business Horizons, 51(4), pp.341-352.

Clark, C., 2008. The impact of entrepreneurs' oral ‘pitch’presentation skills on business angels' initial screening investment decisions. Venture Capital, 10(3), pp.257-279.

Collewaert, V., 2012. Angel investors’ and entrepreneurs’ intentions to exit their ventures: A conflict perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), pp.753-779.

Colombo, M.G. and Grilli, L., 2010. On growth drivers of high-tech start-ups: Exploring the role of founders' human capital and venture capital. Journal of business venturing, 25(6), pp.610-626.

Cornwall, J.R., Vang, D.O. and Hartman, J.M., 2015. Bootstrapping. In Entrepreneurial Financial Management (pp. 186-202). Routledge.

Cuñat, V. and Garcia-Appendini, E., 2012. Trade credit and its role in entrepreneurial finance. Oxford handbook of entrepreneurial finance, pp.526-557.

Dimov, D., 2010. Nascent entrepreneurs and venture emergence: Opportunity confidence, human capital, and early planning. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), pp.1123-1153.

Eckermann, M. (2006). Venture Capitalists¿ Exit Strategies under Information Asymmetry. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Ferrary, M. and Granovetter, M., 2009. The role of venture capital firms in Silicon Valley's complex innovation network. Economy and society, 38(2), pp.326-359.

Festel, G.W. and De Cleyn, S.H., 2013. Founding angels as an emerging subtype of the angel investment model in high-tech businesses. Venture capital, 15(3), pp.261-282.

Gassmann, O. (2016). Management of the fuzzy front end of innovation. [Place of publication not identified]: SPRINGER INTERNATIONAL PU.

Gompers, P. and Lerner, J. (1998). The determinants of corporate venture capital success. [Boston]: Division of Research, Harvard Business School.

Groh, A.P. and von Liechtenstein, H., 2011. The first step of the capital flow from institutions to entrepreneurs: The criteria for sorting venture capital funds. European Financial Management, 17(3), pp.532-559.

Harrison, R., Mason, C. and Robson, P., 2010. Determinants of long-distance investing by business angels in the UK. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(2), pp.113-137.

Häussler, C., Harhoff, D. and Müller, E., 2012. To be financed or not…-The role of patents for venture capital-financing. ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper, (09-003).

Hellmann, T. (1998). The Allocation of Control Rights in Venture Capital Contracts. The RAND Journal of Economics, 29(1), p.57.

Hellmann, T. and Puri, M. (1999). The Interaction between Product Market and Financing Strategy: The Role of Venture Capital. SSRN Electronic Journal, pp.The Review of Financial Studies, Volume 13, Issue 4, October 2000, Pages 959–984.

Hmieleski, K.M. and Carr, J.C., 2008. The relationship between entrepreneur psychological capital and new venture performance. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research.

Hoffman, A. (2018). How Will Venture Capital Change In The Next Decade?. [online] Forbes.com. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/quora/2018/03/09/how-will-venture-capital-change-in-the-next-decade/#16df92027c18 [Accessed 24 Nov. 2019].

Investopedia. (2019). Venture Capitalist (VC) Definition. [online] Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/v/venturecapitalist.asp [Accessed 19 Nov. 2019].

Ivashina, V., 2009. Asymmetric information effects on loan spreads. Journal of financial Economics, 92(2), pp.300-319.

Jayawarna, D., Jones, O. and Marlow, S., 2015. The influence of gender upon social networks and bootstrapping behaviours. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(3), pp.316-329.

Kaplan, S. and Strömberg, P. (2001). Venture Capitalists as Principals: Contracting, Screening, and Monitoring. American Economic Review, 91(2), pp.426-430.

Keil, T., Autio, E. and George, G., 2008. Corporate venture capital, disembodied experimentation and capability development. Journal of Management Studies, 45(8), pp.1475-1505.

Keil, T., Maula, M.V. and Wilson, C., 2010. Unique resources of corporate venture capitalists as a key to entry into rigid venture capital syndication networks. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(1), pp.83-103.

Kirsch, D., Goldfarb, B. and Gera, A., 2009. Form or substance: the role of business plans in venture capital decision making. Strategic Management Journal, 30(5), pp.487-515.

Klapper, L.F. and Love, I., 2011. Entrepreneurship and development: the role of information asymmetries. The World Bank Economic Review, 25(3), pp.448-455.

Klausner, M. and Litvak, K., 2017. What economists have taught us about venture capital contracting. In Bridging the Entrepreneurial Financing Gap (pp. 54-74). Routledge.

Ley, A. and Weaven, S., 2011. Exploring agency dynamics of crowdfunding in start-up capital financing. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 17(1).

Litvak, K., 2009. Venture capital limited partnership agreements: Understanding compensation arrangements. The University of Chicago Law Review, pp.161-218.

Manchanda, K. and Muralidharan, P., 2014. Crowdfunding: a new paradigm in start-up financing. In Global Conference on Business & Finance Proceedings (Vol. 9, No. 1, p. 369). Institute for Business & Finance Research.

Manigart, S. and Sapienza, H., 2017. Venture capital and growth. The Blackwell handbook of entrepreneurship, pp.240-258.

Masulis, R.W. and Nahata, R., 2011. Venture capital conflicts of interest: Evidence from acquisitions of venture-backed firms. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 46(2), pp.395-430.

Maxwell, A.L., Jeffrey, S.A. and Lévesque, M., 2011. Business angel early stage decision making. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(2), pp.212-225.

Mishra, C. and Zachary, R. (2014). The Theory of Entrepreneurship. pp.143-145. Mollick, E.R., 2013. Swept away by the crowd? Crowdfunding, venture capital, and the selection of entrepreneurs. Venture Capital, and the Selection of Entrepreneurs (March 25, 2013).

Parhankangas, A. and Ehrlich, M., 2014. How entrepreneurs seduce business angels: An impression management approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(4), pp.543-564.

Park, H.D. and Tzabbar, D., 2016. Venture capital, CEOs’ sources of power, and innovation novelty at different life stages of a new venture. Organization Science, 27(2), pp.336-353.

Patel, P.C., Fiet, J.O. and Sohl, J.E., 2011. Mitigating the limited scalability of bootstrapping through strategic alliances to enhance new venture growth. International Small Business Journal, 29(5), pp.421-447.

Politis, D., 2008. Business angels and value added: what do we know and where do we go?. Venture capital, 10(2), pp.127-147.

Ramaraju, S.P., Kim, S.T. and Kim, C., 2017. A Comparative Analysis on the Growth Stage of E-Business: Focusing on Korea and India. IJICTDC, 2(2), pp.23-35.

Rider, C.I., 2009. Constraints on the control benefits of brokerage: A study of placement agents in US venture capital fundraising. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54(4), pp.575-601.

Schwienbacher, A. and Larralde, B., 2010. Crowdfunding of small entrepreneurial ventures. Handbook of entrepreneurial finance, Oxford University Press, Forthcoming.

Shepherd, D. and Zacharakis, A. (1999). Conjoint analysis: A new methodological approach for researching the decision policies of venture capitalists. Venture Capital, 1(3), pp.197-217.

Stam, W., Arzlanian, S. and Elfring, T., 2014. Social capital of entrepreneurs and small firm performance: A meta-analysis of contextual and methodological moderators. Journal of business venturing, 29(1), pp.152-173.

Strebulaev, I. and Gornall, W. (2015). How Much Does Venture Capital Drive the U.S. Economy?. [online] Stanford Graduate School of Business. Available at: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/how-much-does-venture-capital-drive-us-economy [Accessed 17 Nov. 2019].

Timmons, J. and Bygrave, W. (1986). Venture capital's role in financing innovation for economic growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(2), pp.161-176.

Tomczak, A. and Brem, A., 2013. A conceptualized investment model of crowdfunding. Venture Capital, 15(4), pp.335-359.

Trester, J. (1998). Venture capital contracting under asymmetric information. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22(6-8), pp.675-699.

Vilajosana, I., Llosa, J., Martinez, B., Domingo-Prieto, M., Angles, A. and Vilajosana, X., 2013. Bootstrapping smart cities through a self-sustainable model based on big data flows. IEEE Communications magazine, 51(6), pp.128-134.

Wallnöfer, M. and Hacklin, F., 2013. The business model in entrepreneurial marketing: A communication perspective on business angels' opportunity interpretation. Industrial Marketing Management, 42(5), pp.755-764.

Wash, R., 2013. The value of completing crowdfunding projects. In Seventh International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

Wonglimpiyarat, J., 2016. Exploring strategic venture capital financing with Silicon Valley style. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 102, pp.80-89.

Yang, Y., Narayanan, V.K. and Zahra, S., 2009. Developing the selection and valuation capabilities through learning: The case of corporate venture capital. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(3), pp.261-273.

Yung, C., 2009. Entrepreneurial financing and costly due diligence. Financial Review, 44(1), pp.137-149.

Zacharakis, A., Erikson, T. and George, B. (2010). Conflict between the VC and entrepreneur: the entrepreneur's perspective. Venture Capital, 12(2), pp.109-12

Looking for further insights on Examining the Satyam Financial Reporting Scandal? Click here.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts