NPV in Investment Decisions

Question one

The Present Net Value (NPV) is the value of all the future cashflow s, whether positive or negative, over the whole lifetime of an investment presented to the current audience. Net present worth is a form of intrinsic valuation. It is applicable across various accounting and finance systems to value of a project, business, cost of the program, investment security, and any other program that revolves around cash flow. NPV is a methodology that is based on discounting the projected future cash flow of a business or a project. In a more specific manner, it aims to state that the present value of a project or company ought to exceed the current value of its outflow if a project is to be deemed as profitable (Thiruvady, Blum, and Ernst 2019, p. 21). The cash flow streams involve all the payments and receipts that are linked to the investment project in its economic lifetime, and it ought to be discounted at the opportunity cost of capital that can reflect the risk of the project and the financing mix. NPV as an approach of evaluating projects would present some advantages to the stakeholders, which include;

Reinvestment Assumptions

Unlike other methods of valuation such as IRR, NPV is more sensible since it does not assume that cash flows will be injected back to the Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Reinvesting the cashflow at the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) would mean that one is still investing back the cash flows from the project into the market at an equal rate as that of the businesses project’s rate of return (Leyman and Vanhoucke 2016, p. 139). It would mean that the business will have to find another investment yielding the same as the project for the reinvestment.

Acknowledges the conventional cash flow patterns

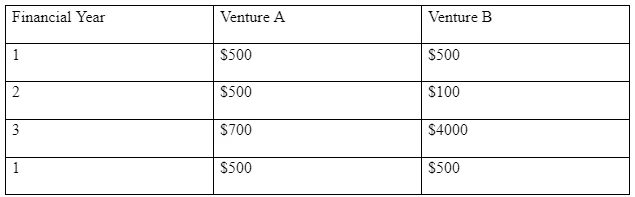

The Net Present Value (NPV) is not affected by conventional cash flow patterns. The traditional cash flow pattern is as follows (this is a hypothetical example)

At the financial year 0, there is a primary outlay, and from the first year, there are positive and negative cash flows. Using other approaches of project valuation such as IRR in this scenario would lead to no IRR or several IRR, which will be a misinterpretation of the capital budgeting decisions among stakeholders. However, under NPV, the stakeholder will not need to be worried when dealing with conventional cash flow patterns.

NPV considers all cashflows

The NPV approach will take into account every cash flow the stakeholders define. It is contrary to the payback period or discounted payback period approach that does not consider cash flows beyond the payback period. For example, the preliminary outlay is $ 1000 at time 0 for projects A and B.

In this case, Venture A looks more lucrative because it recovers its initial outlay in 2 years, while venture B takes more time as compared to venture A. in such a project, the payback period is ignoring the considerable cash flow of $4000. Using NPV, the approach will consider the $4000 and might make a prediction that project B is more lucrative for any stakeholder. Although this prediction is subjected to the discount rate of both projects. However, what is essential is that all NPV will consider all the cashflows defined.

NPV gives a good measure of profitability

If a stakeholder wishes to choose a single project from a group of projects or businesses, then NPV is a relevant measure of profitability (Gaspars-Wieloch 2019, p. 157). If a shareholder uses the IRR framework for the mutually exclusive project, they might end up investing in small projects that have a higher IRR, which are short-term in nature at the expense of choosing long-term and more profitable projects. Typically long-term value creation is in the best interests for most shareholders.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to Investment Proposals.

Factors in Risk Elements

When calculating NPV, one usually uses discount rates, which is the risk of undertaking the business, project, operational risks are factored in this methodology.

Shortcomings of NPV

Despite having some advantages over other approaches, NPV also has some weaknesses that can determinantal to the interests of stakeholders. These shortcomings include;

Approximation of the Opportunity Cost.

The opportunity cost is an important factor when considering the preliminary outlay. Having a clear estimation of this cost is challenging, and at the same time, underestimating the primary outlay is likely to give a false result when calculating NPV. Therefore, stakeholders should first have a clear value on opportunity cost prior to using NPV.

Overlooking Sunk Cost

In budgeting, the sunk cost is the cost incurred before starting a project, for example, a cost incurred in the research and development process. Therefore, the cost could be huge, and ignoring these costs in some cases could become very difficult for the finance team in a business.

Strain in Defining the Obligatory Rate of Return

Defining the rate at which the cash flow ought to be discounted is challenging for the finance team. A business should never use the Weighted Average Cost of Capital as the rate but ought to use the projects’ rate of return as the discount rate. Therefore, an incorrect estimation could lead to higher or lower NPV (Creemers 2018, p. 837). A high-risk ought not to be discounted at its cost of capital, but at its required rate of return.

NPV gives optimistic projections

In most cases, business owners and managers tend to be too optimistic about the success of the study. Since the business’s finance team needs to liaise with the management team to approximate the current and future business environment, the cash flows projected could be too high. Therefore, there is a likelihood that the cashflow given could be very high (Hiesl, Crandall, Weiskittel, Benjamin, and Wagner, 2017, p. 209). Therefore, there could be an existence of upward biases regarding using this method.

NPV could fail to increase Return on Equity and Earnings Per Share

Short term businesses and projects could have a high NPV, which might fail to boost the Return on Equity and Earnings per share of the business. Earnings Per Share and Return on Equity are essential factors that are likely to increase shareholder value. Practically, short term projects and businesses with higher NPV could fail to work in favour of the shareholders.

Variance in Size of Projects

Capital rationing is a situation where a shareholder does not have proper access to funds. Therefore, they would have to choose the project or business that is within their ability or rather capital budget. For mutually exclusive business, a comparison of the NPV of the projects that need a different sum of funds could not be suitable (Shu, Zeithammer, and Payne 2016). For example, in a case where the shareholder has a capital budget of 8 million. The first project needs 11 million and results in an NPV of 3 million, and the second project needs 6 million and leads to an NPV of 1 million. In such a situation, the NPV of the first project and the second one cannot be sufficiently compared for the sake of decision making because the size of both the projects is different.

Overall, despite the disadvantages of NPV, financial managers and shareholders widely use it and perceive it as the best measure for profitability as compared to other approaches such as IRR, the payback period approach, and the discounted payback period approach.

Question Two

Normally, any business is risky and is subjected to various cases that are dependent on either the state policy, regional imbalances, and the international market. These uncertainties have an essential effect on project investment decisions. Identifying these sources of uncertainty is fundamental to obtain the right results. Thus, every uncertainty and its effect ought to be analysed realistically. Leyman, Van Driessche, Vanhoucke, and De Causmaecker (2019) stressed the essence of communicating and compiling all the related business uncertainties and their probability and distribution of occurrence so that company can have reliable results to make the right decisions. However, in a real sense, these uncertainties cannot be accurately predicted as assumed by NPV. These uncertainties include;

Inflation

Ridley has given an estimation of inflation on sales revenue as 8% per year, and the direct project cost to be 4% per year. Practically, it is not possible to have a constant inflation rate throughout the period. Such assumptions are likely to mislead various stakeholders, especially when using the NPV approach. Normally, various factors can affect sales revenue in the first place such as the change in the client’s tastes and preferences, at the same time the inflation in the national economy can also directly affect the sales revenue (Campbell, Anderson, Daugaard, and Naughton 2018, p. 330). An increase in the inflation rate of the national economy is likely to lead to increased inflation in both the direct project cost per year and the sales revenue. Secondly, according to Ridley’s case study, the company will sell its plant and machinery assets at 4 million Euros, when the project ceases. The company might fail to attain the same figure because of economic inflation, which is also determined by various national factors such as the monetary regimes, political dynamics, and economic patterns, among others.

Taxation

According to Ridley’s projections, the tax on annual profits is stated as 20% per annum for all the four years of operation. As much as the taxation of profits has proved to be constant over the years, one can never be certain that this will be the case, because of the changing dynamics in the economy and broadening of tax collection avenues by the government. Secondly, when selling the project’s plants and machinery, the company assumed that they would get4 mill euros after taxation, while this amount is bound to change depending on the tax regime that would exist at this time.

Discounting Rate

As much as companies try to show that the calculation of discount rates is scientific, various assumptions came to play in this process, and all the process does is to come up with the best guess of what is likely to happen in the future. Besides, only one discount rate is applicable in time to value future cash flows. In the case of Ridley, the company’s discounted rate is 7% for all four years, while in a real sense, the interest rates and the risk profiles of companies are always changing dynamically. It is also practical that the project will not have the same level of risk throughout its entire 4-year course. In the case study of a four-year investment, it is challenging for an investor to calculate the NPV if the investment has a high risk of loss in its first year. Still, it would improve to low risk in the last three years of its operations (Montiel, Dimitrakopoulos, and Kawahata 2016, p. 9). For one to determine this aspect, an investor could use different discount rates for every period. However, it would render the model more complicated because it needs the pegging of the five discount rates.

Additional Cost

The model used by Ridley only considers the cash flows of the project. It is even more complicated for Ridley because investing in a new venture, and therefore it is difficult to determine the cash flow from the project (Ehsan, Yang, and Cheng 2018). Hence there is no guaranteed return in Ridley’s cashflows. Besides, the company has failed to include other vital costs that can have a huge effect on the true value of the project. Such costs include opportunity costs and other types of costs that have not been embedded in the initial outlay of the capital.

Question Three

The ideology of NPV is majorly acceptable for the verification of financial justification of planned projects. Normally, a company with a positive NPV is likely to increase the company’s shareholders’ value. However, those with negative NPV, like in the case of Ridley, might fail to increase the shareholders’ value or even decrease it. According to a study by, if a company fails to increase the shareholder value in one specific project, they might consider investing in a project that will increase this value. The authors note that for the company to increase its chances of increasing the shareholder’s value after failing in the first project, the second project ought to have a positive NPV. In the case of Ridley, the NPV is -1.65 million Euros; therefore, it would not be viable to invest in the project if the company aims to reduce the shareholder value (Aloini, Dulmin, Mininno, Raugi, Testi, and Tucci, 2016). Instead, they should consider investing in a project that would guarantee a positive outcome. In cases where there is no provision for investing in the second project to redeem the shareholders’ value, the company should consider paying the cash dividends to its owners. The 38 million Euros that Ridley wants to invest in a negative NPV project, they can consider giving it to their shareholders as dividends to increase their value. Taxes on dividends also decrease cash flows for investors from distributed dividends. Thus, these taxes act as investments for projects with a negative NPV. Such a situation creates an opportunity for shareholders to maximize their value by conducting a comparison between the loss with the existing alternate projects that have a negative NPV, like in the case of NPV. In cases where the loss of value is due to the existence of such taxes is more prevalent than the negative NPV project. It is more justifiable if Ridley would invest the amount rather than paying it out as dividends to shareholders. In some cases, projects with lower values will be of preferences to some shareholders as they prefer projects that have lower risks and low rates of returns. Provisional inefficiencies in the market could lead to the risk of bankruptcy and problems with liquidity. Negative NPV could be a way of free additional cashflows that give room for the company to restructure itself.

Question Four

Debt funding can be expensive in the Long run

Whenever a company uses debt financing capital for a project, they are likely to incur interests. In some cases, these interests can be very high than the current market rate for government securities (Ning and Babich, 2018, p. 1004). It is for the same reason that some financial institutions might be willing to invest in such ventures. Still, it also implies that the business will need to give competitive interest so that they can attract lenders. In most cases, Ridley is likely to find a financing institution that would give them a debt at two to three percent higher than what other creditors would give. There are additional costs that are related to raising the finance (issue costs), which in this case, are 2% of the gross finance required. Therefore, the company would have to incur this cost besides the interests pegged on the debt (De Rassenfosse and Fischer 2016, p. 240). Additionally, loans attract interests that are taxed, which means that Ridley will incur more costs in paying taxes; this is contrary to the payment of dividends, which are not taxed by the government. Besides, the company’s credit history and other facets, such as the state of the market, could be the ultimate determiner on whether debt financing would be appropriate for an organization or not. In the long run, the company might realise that after calculated the discounted interest rates after taxes, one is paying an amount that will compromise into the profits of the company in comparison to other sources of funding.

Cashflows

If a company uses debt financing to finance its operations and projects, it enhances the chances of the entity having various issues in meeting its existing loan obligations in cases of a decrease in cash flow. In this case, Ridley would borrow 40% of the capital required to run the project, which will have to be paid from the cash flows generated by the project. Failure for the project to generate the relevant cash flows from other sources, the company’s business will be hugely affected because there is no guarantee that the sales of the project or the company will go as projected by the company (De Rassenfosse and Fischer 2016, p. 240).

Limitations due to debts

Debt instruments have some restrictions on the activities that the company conducts, which hinders the management from undertaking other financing options and non-essential business opportunities (Deloof, La Rocca, and Vanacker 2019). For example, in the case of Ridley, the company will acquire 60% of its finances form a subsidised loan scheme run by the government, which will eventually limit the company from undertaking other available financing instruments because it has committed itself to the former, even if these options offer better terms.

Debt Financing is Considered Risky

A company with a large amount of debt could be perceived to be risky by the leaders and potential investors. If Ridley uses 100% debt financing, it could be considered as risky, which can lead to reduced investor base, because most investors are afraid of investing in a debt-ridden company. At the same time, future lenders would be wary of the same company. Apart from losing stakeholders and other lenders, the interests can change dramatically in regards to the repayment dates. In the event of the maturing balloon debts, the company cannot be guaranteed of availability of capital in the future or when they need additional financing in the middle of the project (Ghouma, Ben-Nasr, and Yan 2018, p. 145). In cases, where the financing is a revolving credit line, financial institutions have a history of cutting their clients off when they need the money most, which could hamper the overall performance and outcomes of the project.

Collateral

Before any financial institution would give out loans, they would need collateral, which is equivalent to the sum being borrowed or even more. In this case, Ridley is likely to use its assets as collateral for the loan. It means that as long the company is serving the debt, they cannot sell these assets; neither can they dispose of them.

References

Aloini, D., Dulmin, R., Mininno, V., Raugi, M., Testi, D., and Tucci, M., 2016. Investment evaluation under multiple uncertainties: optimal sizing and configuration of an integrated energy production system by renewable sources. In the Nineteenth International Working Seminar on Production Economics (pp. 1-12). AUT.

Campbell, R.M., Anderson, N.M., Daugaard, D.E. and Naughton, H.T., 2018. Financial viability of biofuel and biochar production from forest biomass in the face of market price volatility and uncertainty. Applied Energy, 230, pp.330-343.

Creemers, S., 2018. Moments and distribution of the net present value of an on-going project. European Journal of Operational Research, 267(3), pp.835-848.

Ehsan, A., Yang, Q. and Cheng, M., 2018. A scenario-based robust investment planning model for a multi-type distributed generation under uncertainties. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution, 12(20), pp.4426-4434.

Hiesl, P., Crandall, M.S., Weiskittel, A., Benjamin, J.G., and Wagner, R.G., 2017. Evaluating the long-term influence of alternative commercial thinning regimes and harvesting systems on the projected net present value of precommercially thinned spruce–fir stands in northern Maine. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 47(2), pp.203-214.

Leyman, P., Van Driessche, N., Vanhoucke, M., and De Causmaecker, P., 2019. The impact of solution representations on heuristic net present value optimization in discrete time/cost trade-off project scheduling with multiple cash flow and payment models. Computers & Operations Research, 103, pp.184-197.

Montiel, L., Dimitrakopoulos, R., and Kawahata, K., 2016. Globally optimising open-pit and underground mining operations under geological uncertainty. Mining Technology, 125(1), pp.2-14.

Ning, J., and Babich, V., 2018. R&D investments in the presence of knowledge spillover and debt financing: Can risk-shifting cure free-riding?. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 20(1), pp.97-112.

Thiruvady, D., Blum, C., and Ernst, A.T., 2019, January. Maximising the net present value of project schedules using CMSA and parallel ACO. In International Workshop on Hybrid Metaheuristics (pp. 16-30). Springer, Cham.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts