Research and Practice

Effect of a Two-Year Obesity Prevention Intervention on Percentile Changes in Body Mass Index and

Academic Performance in Low-Income Elementary

School Children

Danielle Hollar, PhD, MHA, Sarah E. Messiah, PhD, MPH, Gabriela Lopez-Mitnik, MPhil, MS, T. Lucas Hollar, PhD, Marie Almon, RD, MS, and Arthur S. Agatston, MD

The prevalence of obesity remains high among all age and racial groups in the United States, particularly among African Americans, His panic and Mexican Americans, and low-income children.1,2 Childhood-onset obesity is related to numerous risk factors for cardiometabolic dis ease that track from childhood into adulthood, including elevated blood pressure and lipids.3–8 Additionally, studies have documented the mental health consequences of childhood obe sity, including low self-esteem and higher rates of anxiety disorders, depression, and other psycho pathologies among overweight and obese chil dren.9–12 How childhood overweight affects academic performance, however, is less well understood. Studies show that in addition to socioeco nomic status, obesity, poor nutrition, and food insufficiency affect a child’s school achieve ment.13–18 Specifically, students who experience food insufficiency may have lower math scores, social difficulties, and psychological difficul ties.15,16 Children described as normal-weight or Objectives. healthcare dissertation help can provide valuable insights into how these factors interact and contribute to academic and mental health outcomes in children. We assessed the effects of a school-based obesity prevention intervention that included dietary, curricula, and physical activity components on body mass index (BMI) percentiles and academic performance among low income elementary school children. Methods. The study had a quasi-experimental design (4 intervention schools and 1 control school; 4588 schoolchildren; 48% Hispanic) and was conducted over a 2-year period. Data are presented for the subset of the cohort who qualified for free or reduced-price school lunches (68% Hispanic; n= 1197). Demographic and anthropometric data were collected in the fall and spring of each year, and academic data were collected at the end of each year. Results. Significantly more intervention than control children stayed within normal BMI percentile ranges both years (P=.02). Although not significantly so, more obese children in the intervention (4.4%) than in the control (2.5%) decreased their BMI percentiles. Overall, intervention schoolchildren had signif icantly higher math scores both years (P.001). Hispanic and White intervention schoolchildren were significantly more likely to have higher math scores (P.001). Although not significantly so, intervention schoolchildren had higher reading scores both years. Conclusions. School-based interventions can improve health and academic performance among low-income schoolchildren. (Am J Public Health. 2010;100: 646–653. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.165746) overweight (versus obese) who are at nutritional risk have lower math scores, poorer attendance, and more behavior problems.13,14 Moreover, young children who become overweight be tween kindergarten and the end of third grade experience reductions in test scores.17,18 Addi tionally, severely obese children have been shown to have lower IQs, poorer school perfor mance, and lower test scores than their less overweight classmates, even after control for behavioral and socioeconomic variables.19–21 Schools play a crucial role in improving the health, and in turn the academic performance, of students. Children generally attend school 5 days per week throughout most of the year, and schools in the United States are located in communities of every socioeconomic and racial/ethnic group. The school environment provides many opportunities to teach children about important health and nutrition practices. The influence of schools on the health of children is strong, especially in low-income communities, where children often receive a significant proportion of their daily nutrition requirements (as much as 51% of daily energy intake)22 via the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program. Healthier Options for Public Schoolchildren (HOPS) was an elementary school–based obe sity prevention intervention targeting children aged 6 to 13 years that included nutrition and physical activity components. The goal was to improve overall health status and academic achievement by using replicable strategies.

METHODS

The pilot study described here was imple mented over 2 school years (2004–2005 and 2005–2006) and included 6 elementary schools (4588 children; 48% Hispanic) in Osceola, Florida. All schools had similar de mographic and socioeconomic characteristics and were chosen from a convenience sample. In a quasi-experimental design, schools were nonrandomly assigned to 1 of 4 intervention

646 | Research and Practice | Peer Reviewed | Hollar et al. American Journal of Public Health | April 2010, Vol 100, No. 4

schools or 1 of 2 control schools by school administration. Because 1 control school was found after the start of the study to have an exceptional physical education program (state and federal grants including the Carol M. White Physical Education Program [PEP] grant) that could potentially confound the results (which was ultimately supported by post hoc analyses), it was removed from the sample.

Dietary intervention. The dietary intervention consisted of modifications to school-provided breakfasts, lunches, and extended-day snacks in the intervention schools. Menus were mod ified to include (1) more high-fiber items (e.g., whole grains and fresh fruits and vegetables); (2) fewer high-glycemic items (e.g., high-sugar cereals and processed flour goods); and (3) lower amounts of total, saturated, and trans fats. These modifications included the substi tution of healthier ingredients for less healthy ingredients, rather than an outright ban on ‘‘child-friendly’’ foods. For example, chicken patties coated with whole grain flour were served instead of patties coated with white flour, and reduced-fat dairy products, includ ing USDA Foods (also known as ‘‘USDA Commodities’’), were provided in place of whole-milk (higher fat) products. Study staff, including a registered dietitian, worked closely with the USDA Food and Nutrition Service, as well as the school administration and foodservice personnel, to ensure inter vention fidelity. Nutrition analyses of break fast and lunch menus showed that inter vention menus, on average, contained

Intervention

HOPS was designed to test the combined effect of (1) including nutritious ingredients and whole foods (e.g., as close to original form, and thus most nutritious as possible, such as fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains) ac quired through public school food distribution networks, in USDA NSLP school-provided meals, which provided daily examples of the good nutrition principles taught in the educa tion curricula; (2) providing a nutrition and healthy lifestyle curricula that taught elemen tary-aged children and adults about good nu trition and healthy lifestyle management, in cluding an emphasis on increased levels of physical activity; and (3) fostering other school based wellness activities such as gardens. Dietary intervention. The dietary intervention consisted of modifications to school-provided breakfasts, lunches, and extended-day snacks in the intervention schools. Menus were mod ified to include (1) more high-fiber items (e.g., whole grains and fresh fruits and vegetables); (2) fewer high-glycemic items (e.g., high-sugar cereals and processed flour goods); and (3) lower amounts of total, saturated, and trans fats. These modifications included the substi tution of healthier ingredients for less healthy ingredients, rather than an outright ban on ‘‘child-friendly’’ foods. For example, chicken patties coated with whole grain flour were served instead of patties coated with white flour, and reduced-fat dairy products, includ ing USDA Foods (also known as ‘‘USDA Commodities’’), were provided in place of whole-milk (higher fat) products. Study staff, including a registered dietitian, worked closely with the USDA Food and Nutrition Service, as well as the school administration and foodservice personnel, to ensure inter vention fidelity. Nutrition analyses of break fast and lunch menus showed that inter vention menus, on average, contained

Dig deeper into Marketing in a Digital Age and Corporate Social Responsibility with our selection of articles.

RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

approximately twice as much fiber and 23% less fat than did control menus.23–25 Curricula component. The curricula compo nent consisted of a school-based holistic nutrition and healthy lifestyle management program for elementary-aged children and adults. These curricula sought to teach chil dren, parents, and school staff about good nutrition and the benefits of daily physical activity with the goal of improving the health and academic achievement of children in a replicable and sustainable manner. Replica tion and sustainability were assisted by incor porating USDA Team Nutrition materials, which are available to US schools, as well as The OrganWise Guys (The OrganWise Guys Inc., Duluth, GA; https://www.organwiseguys. com), which is used by many USDA county extension agents in the United States who conduct nutrition education in low-income schools every day. Programming included a monthly thematic set of nutrition activities developed by the study staff in collaboration with elementary school education experts. Each month, a multi media set of educational materials that high lighted nutrient-dense foods and healthy life style management lessons were sent to the intervention schools. The materials included Foods of the Month posters, tips for conducting Foods of the Month tastings, Foods of the Month parent newsletter inserts, Foods of the Month activity packets, healthy lifestyle hand outs, school gardening instructions, and other materials aligned with special programming such as American Heart Health Month, Na tional Nutrition Month, and National School Breakfast and Lunch Weeks. In addition to the monthly educational pro gramming, each intervention school received an OrganWise Guys kit. The OrganWise Guys curriculum integrates nutrition, physical activ ity, and other lifestyle behavior messages to help children understand the importance of making healthy lifestyle choices and to moti vate them to make these changes in their own lives. The OrganWise Guys kit includes print (books and activity posters) and electronic (videos and Internet activities) media, as well as school assemblies and a physical activity pro gram (WISERCISE!, described below). Fruit and vegetable gardens at intervention schools provided a fun and creative component to the nutrition curriculum, with the goal of teaching children how the nutritious fruits and vegetables served in their school cafeterias, their homes, and in restaurants are grown, cultivated, and harvested. Sustainability was assisted by USDA master gardeners. Physical activity component. The physical activity component, which varied among the intervention schools, consisted of increased opportunities for physical activity during the school day in ways that were feasible within the constraints of testing mandates. In Florida, acceptance of more time for physical activity was difficult until the governor mandated 150 minutes of physical activity, per week, for elementary school children, which was not passed until the fall of 2007 in Florida House Bill CS/CS/HB 967–Physical Education.26 Thus, the amount and types of physical activity varied among intervention schools throughout the study. Year 1 did not include a physical activity intervention. At the beginning of study year 2, students were provided pedometers and OrganWise Guys tracking books to record the number of steps taken each day. However, the pedometers broke easily and the students often lost them. Therefore, although a previous study showed that a pedometer program was useful in increasing the daily physical activity of children by approximately 1000 more steps per day as compared with that in nonpartici pants,27 the use of pedometers was discontinued midyear in our study during year 2. Schools were asked instead to conduct daily physical activity in the classroom during regular class room time by using a 10- to 15-minute desk-side physical activity program (WISERCISE!, The OrganWise Guys Inc; or TAKE10!, ILSI Re search Foundation, Washington, DC). These desk-side physical activities are matched with core academic areas, such as spelling and math, which allows teachers to stay on task while increasing the daily physical activity of their students. Schools also were asked to implement structured physical activity during recess and to lead other activities, such as walking clubs, that encouraged children and adults to increase their physical activity each day. Measures Demographic and anthropomorphic infor mation—including date of birth, gender, grade, and race/ethnicity—were collected

April 2010, Vol 100, No. 4 | American Journal of Public Health Hollar et al. | Peer Reviewed | Research and Practice | 647

each fall and spring (2004–2006). The participants were asked to remove their shoes and heavy outer clothing and to empty their pockets before being measured. Anthropometric data included height (by stadiometer: Seca 214 Road Rod Portable Stadiometer, Seca North America East, Hanover, MD) and weight (by balance scale: LifeSource 321 Scale, A&D Medical, San Jose, CA), which were used to create an age- and gender-specific body mass index (BMI; weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) percentile score. Children were classified according to BMI percentile for age and gender in accordance with the Centers for Disease Control and Pre vention standardized groups as follows: (1) normal weight (BMI less than 85th percentile), (2) at risk for overweight (BMI 85th percen tile or higher but less than 95th percentile), and (3) obese (BMI 95th percentile or higher).28 The Florida Comprehensive Achievement Test (FCAT) is administered to all Florida public school children beginning in the third grade. The average score throughout the state is 300. A score of 300 to 399 (level 3) indicates that a student answered many ques tions correctly but was generally less successful with questions involving the most challenging content. Level 3 meets the state learning re quirements and allows students to matriculate to the next grade level. A score of 200 to 299 (level 2) meets the minimum requirements only and indicates that a student had limited success with challenging content on the FCAT. A level 2 in certain years (grade 3 for example) on certain portions of the FCAT could result in students being retained in their current grade level per the Florida Board of Educa tion.29 FCAT reading and math scores for each child were provided by school administration.

RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

Data Analysis

The analysis presented here included chil dren who qualified for free or reduced-price meals in the USDA NSLP proxy. Free meals are available to children from families with in comes at or below 130% of the poverty level; reduced-price meals are available to children from families with incomes between 130% and 185% of the poverty level. For example, for the period July 1, 2008, through June 30, 2009, 130% of the poverty level was $27560 for a family of 4; 185% was $39220.30 By in cluding children who most likely received school provided lunch every day, we improved the intervention’s internal validity and thus de creased potential confounders (e.g., children with a higher socioeconomic status likely eat better in general, regardless of eating the school lunch, and are more likely to bring lunch from home). The unit of analysis for this pilot study was a school rather than an individual; thus, cluster randomization was taken into account. With cluster randomization, the mean response un der each experimental condition is subject to 2 sources of variation: cluster-to-cluster and across individuals within a cluster. Approach ing the analytical plan from an individual level only, rather than a cluster level, would not take into account the between-cluster variation and can cause an inflation of type I errors in which any intervention effect may become confounded with the natural cluster to-cluster variability. Although we realize that this trial did not include a large number of schools to conduct a robust cluster analysis, we applied a 2-stage approach to the data analysis. The first stage was at the individual level. In this first stage, we analyzed all individual-level covariates to derive school-specific means that were adjusted for individual-level covariates. The second stage was at the school level. In the second stage, we analyzed school-specific means and appropriately adjusted for school specific covariates to evaluate any intervention effects. The univariate analysis consisted of simple frequency statistics for all demographic vari ables. Chi-square analyses were performed to test for associations between the intervention condition and demographic characteristics. Tests for independent samples were applied to capture differences in the percentages of change in BMI percentile group from baseline to the end of the intervention. For all children aged 2 to 20 years, BMI-for-age was used to assess weight in relation to stature and to calculate z-scores that were based on the 2000 CDC growth charts.31 Repeated-measures analysis tested for changes in trends over time (the 2-year study period, or 4 points in time) in BMI percentile group and FCAT scores. All tests were 2-tailed and P<.05 was considered statistically signifi cant. For the repeated-measures analysis, only those children who had data in both years were retained in the final models. For the repeated measures analysis of BMI, the sample size was 645 children. For the repeated-measures anal ysis of the FCAT scores, the sample size was 350. All analyses were performed by using both the SAS version 9.1(SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and SPSS version 15 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

A total of 1197 children who qualified for free or reduced-price meals through the USDA NSLP were included in the analysis (68% Hispanic, 9% Black, 15% White, 8% other; mean age=7.846 1.67 years). A total of 974 children were in the intervention schools and 199 were in the control school. There were no TABLE 1—Change in BMI Percentile Group by HOPS Intervention Condition, Fall 2004 Through Spring 2006 Same in Fall 2004 and Spring 2006 Decrease Between Fall 2004 and Spring 2006 Increase Between Fall 2004 and Spring

BMI Percentile in Fall 2004 Intervention, % (SD) Control, % (SD) P Intervention, % (SD) Control, % (SD) P Intervention, % (SD) Control, % (SD) P Normal (BMI < 85%) 52.1 (50) 40.7 (49) .02 ... ... 8.1 (27) 11.9 (32) .24 Overweight (85% < BMI < 95%) 7.3 (26) 8.5 (27) .67 6.4 (24) 6.8 (25) .87 4.1 (19) 6.8 (25) .27 Obese (BMI 395%) 17.6 (38) 22.9 (42) .18 4.4 (20) 2.5 (15) .27 ... ... Note. BMI = body mass index; HOPS = Healthier Options for Public Schoolchildren.

Academic Results

significant differences between the interven tion and control groups in gender (P=.063) or the proportion of Blacks (P=.950), Hispanics (P=.063), or children of other ethnicity (P=.42), but there was a significant difference in the proportion of Whites (P=.002). Specif ically, in the intervention schools, 69.6% were Hispanic,13.7% were White, 8.8% were Black, and 7.9% were of other ethnicity. In the control school, 62.2% were Hispanic, 23.0% were White, 8.2% were Black, and 6.6% were of other ethnicity. There was no significant difference between the intervention and con trol schools in the percent of children who were overweight or obese (P=.06). Anthropometric Results As shown in Table 1, significantly more children in the intervention schools than in the control school stayed within the normal BMI percentile range for both years of the study (P=.02). Although not statistically significant (P=.27), more obese children (4.4%) in the intervention schools than in the control school (2.5%) decreased their BMI percentile. Con versely, fewer intervention children in the normal (8.1%) and at-risk-for-overweight (4.1%) groups gained weight versus the same 2 groups in the control school (11.9% and 6.8%, respectively) during the 2 intervention years (P=.24 and P=.27, respectively). Academic Results No significant differences were found at baseline in either math or reading FCAT scores between the intervention and control schools (P=.46 and P=.68, respectively). Overall, as shown in Table 2, intervention children had significantly higher FCAT math scores than did

RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

TABLE 2—Change in Raw Math and Reading by HOPS Intervention Condition from 2003–2004 to 2005–2006 School Years for Overall Sample and by Ethnicity FCAT Raw Score FCAT Raw Score FCAT Raw Score Pa 2003–2004, Mean (SD) 2004–2005, Mean (SD) 2005–2006, Mean (SD) All students Math .001 Intervention 285.6 (58.7) 296.4 (59.3) 307.9 (51.3) Control 279.2 (45.0) 285.5 (53.8) 276.2 (60.9) Reading .08 Intervention 286.7 (64.2) 291.3 (59.8) 292.4 (57.7) Control 282.9 (55.4) 279.9 (65.7) 281.7 (55.8) Hispanic students Math .006 Intervention 281.7 (61.0) 290.8 (62.4) 303.4 (52.7) Control 277.9 (46.8) 281.2 (59.8) 270.1 (67.6) Reading .09 Intervention 282.4 (65.5) 284.7 (61.6) 288.2 (57.7) Control 275.7 (62.2) 269.9 (72.1) 276.8 (58.1) White students Math Intervention 309.3 (54.8) 319.8 (43.5) 330.8 (39.7) .016 Control 292.9 (37.4) 304.7 (29.1) 299.7 (36.6) Reading .16 Intervention 308.5 (60.8) 320.0 (43.4) 315.5 (54.6) Control 297.6 (23.2) 306.4 (45.1) 294.7 (53.9) Black students Math .04 Intervention 270.9 (34.0) 306.8 (46.4) 311.5 (41.5) Control 243.8 (22.3) 264.8 (52.2) 267.6 (44.1) Reading .53 Intervention 265.5 (51.8) 302.1 (51.2) 294.9 (53.3) Control 284.8 (59.2) 287.8 (54.6) 279.6 (33.2) Note. FCAT = Florida Comprehensive Achievement Test; HOPS = Healthier Options for Public Schoolchildren. aP value for the difference between the intervention and control schools from fall 2004 to spring 2006. the control children in both years of the in tervention (P<.001). We found a similar trend for FCAT reading scores in the overall sample, although the difference was not statistically significant (P=.08). After we controlled for ethnic group, the repeated-measures ANOVA showed that in both study years, all 3 ethnic intervention groups showed a statistically sig nificant improvement in FCAT math scores compared with the control groups. Specifically, Hispanic children in the intervention schools showed an over 20-point gain in FCAT math scores versus Hispanic children in the control school, whose scores decreased over the same time period (P=.006). Similarly, both Black and White students in the intervention schools had statistically significant gains of over 40 points (P<.05) and over 20 points (P<.02), respectively, versus the same ethnic group in the control schools. When we dichotomized the FCAT math scores by both level 2 and level 3, the same trends were found as in the raw scores (Table 3), that is, significant gains for the intervention schools versus the control school (P=.008 and P=.001, respectively). After we controlled for ethnic group, we found a significant improve ment in math scores greater than or equal to level 3 for Hispanics (P=.004) and for non Hispanic Whites (P=.04). Math scores greater than or equal to level 2 improved in non Hispanic Blacks (P=.002), and reading scores greater than or equal to level 2 significantly improved as well (P=.05). Although not statistically significant (P=.08), the same overall trends were seen for FCAT reading scores. Intervention children showed gains in FCAT reading scores in both years of the intervention, whereas control school stu dents showed a decrease in mean FCAT read ing scores during the same time period. After control for ethnicity, all 3 ethnic groups in the April 2010, Vol 100, No. 4 | American Journal of Public Health Hollar et al. | Peer Reviewed | Research and Practice | 649

RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

TABLE 3—Percentage of Children at Levels 2 and 3 and Above in FCAT Math and Reading by HOPS Intervention Condition, School Years 2004–2005 and 2005–2006

School Year 2004–2005, % (SD) School Year 2005–2006, % (SD) Pa School Year 2004–2005, % (SD) School Year 2005–2006, % (SD) Pa

All students

Math .008 .001 Intervention 80.4 (40) 85.5 (35) 54.0 (49) 64.5 (47) Control 74.3 (44) 67.1 (47) 41.4 (49) 32.9 (47) Reading .85 .55 Intervention 76.1 (43) 73.6 (44) 54.7 (49) 53.6 (49) Control 75.7 (43) 75.7 (43) 50.0 (50) 51.4 (50) Hispanic students Math .15 .004 Intervention 77.4 (42) 82.1 (38) 50.3 (50) 61.5 (48) Control 72.3 (45) 70.2 (46) 36.2 (48) 25.5 (44) Reading .74 .47 Intervention 72.3 (45) 72.3 (45) 50.3 (50) 51.3 (50) Control 70.2 (46) 70.2 (46) 42.6 (49) 48.9 (50) White students Math .08 .04 Intervention 89.2 (31) 97.3 (16) 67.6 (47) 91.9 (27) Control 86.7 (35) 73.3 (46) 60.0 (50) 53.3 (51) Reading .20 .50 Intervention 91.9 (27) 83.8 (37) 78.4 (41) 67.6 (47) Control 93.3 (26) 100.0 (00) 86.7 (35) 73.3 (46) Black students Math .002 .43 Intervention 88.9 (32) 92.6 (26) 55.6 (50) 55.6 (50) Control 33.3 (57) 33.3 (58) 33.3 (57) 33.3 (58) Reading .05 .15 Intervention 81.5 (39) 70.4 (46) 59.3 (50) 51.9 (51) Control 33.3 (57) 33.3 (58) 00.0 (00) 33.3 (58) Note. FCAT = Florida Comprehensive Achievement Test; HOPS = Healthier Options for Public Schoolchildren. aP value for the difference between the intervention and control schools. intervention schools gained points in FCAT reading scores over the 2-year intervention, whereas White and Black control school chil dren showed decreases in scores (Table 2). When the FCAT results were stratified by BMI percentile group (Table 4), we saw signif icant improvements in math scores greater than or equal to level 3 for those in the intervention schools who were normal weight (P<.004) or obese (P<.004). We also found significant improvements in the intervention school children for math scores greater than or equal to level 2 for those who were obese (P<.003). DISCUSSION To our knowledge, this pilot project is one of the first to examine the effect of a school based obesity prevention intervention on weight and academic performance simulta neously among low-income children. Our lon gitudinal analysis showed that over the 2-year period, children attending the intervention schools, regardless of ethnic background, were significantly more likely to have higher FCAT math scores than were children in the control school. Although not statistically sig nificant, a similar trend was found for FCAT reading scores (Tables 2 and 3). Similarly, weight decreases were noted in the interven tion schools compared with the control school (Table 1). These findings indicate that school based interventions targeting obesity preven tion can have indirect positive effects on academic performance among low-income children who are at high risk for both obesity and poor academic achievement. Few studies have tested the hypothesis that a school-based obesity-prevention inter vention is effective at improving both overall health and academic performance, among high-risk children in particular. The Child and 650 | Research and Practice | Peer Reviewed | Hollar et al. American Journal of Public Health | April 2010, Vol 100, No. 4

RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

TABLE 4—Distribution of Children at FCAT Math and Reading Levels 2 and 3 by BMI Percentile Group and HOPS Intervention Condition, School Years 2004–2005 and 2005–2006

School Year 2004–2005, Mean (SD) School Year 2005–2006, Mean (SD) Pa FCAT Level 2 School Year 2004–2005, Mean (SD) School Year 2005–2006, Mean (SD) Pa Normal (BMI < 85%) .08 .25 Intervention 76.3 (42) 84.2 (36) 75.0 (43) 73.7 (44) Control 72.4 (45) 62.1 (49) 82.8 (38) 82.8 (38) Overweight (85% < BMI < 95%) .78 .48 Intervention 84.0 (37) 84.0 (37) 82.0 (38) 80.0 (40) Control 86.7 (35) 86.7 (35) 80.0 (41) 66.7 (48) Obese (BMI 395%) .003 .79 Intervention 86.5 (34) 89.2 (31) 74.3 (43) 68.9 (46) Control 69.2 (47) 61.5 (49) 65.4 (48) 73.1 (45) FCAT Level 3 Normal (BMI < 85%) .004 .62 Intervention 52.0 (50) 63.15 (48) 55.9 (49) 55.9 (49) Control 37.9 (49) 27.58 (45) 51.7 (50) 51.7 (50) Overweight (85% < BMI < 95%) .61 .92 Intervention 48.0 (50) 72.00 (45) 52.0 (50) 44.0 (50) Control 53.3 (51) 53.33 (51) 46.7 (51) 46.7 (51) Obese (BMI 395%) .004 .78 Intervention 62.2 (48) 62.16 (48) 54.1 (50) 55.4 (50) Control 38.5 (49) 26.92 (45) 50.0 (50) 53.8 (50) Note. BMI = body mass index; FCAT = Florida Comprehensive Achievement Test; HOPS = Healthier Options for Public Schoolchildren. aP value for the difference between the intervention and control schools. Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH), a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored multicenter, school-based intervention study promoting healthy eating, physical activity, and tobacco nonuse by ele mentary students, is probably the most widely known school-based intervention program.32 CATCH analyses that were not stratified by socioeconomic status showed no statistically significant changes in obesity, blood pressure, or serum lipids in the intervention group com pared with controls. Although our study did not measure changes in serum lipids, we did find significant differences in blood pressure (reported elsewhere)33 and positive changes in both weight and academic achievement. Simi larly, several studies have reported associations between diet or nutrition and academic perfor mance, but few have examined children at the highest risk.13–17 Other studies noted that obesity and overweight inhibit academic performance, that physical activity reduces overweight and obesity, and that physical activity increases aca demic performance.34,35 Although we did not include measures to quantify physical activity, it was an integral component of the intervention. Our intervention has implications for na tional school and agricultural policy. School based nutrition programs such as the one de scribed here offer assistance in alleviating poor nutrition and food insufficiency. The Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 man dates the development of wellness policies at every elementary school that participates in the USDA NSLP. Other federal nutrition-based initiatives, such as USDA technical assistance to school foodservice departments, the Institute of Medicine’s Committee to Review the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs Meal Patterns and Nutrient Standards, and increases in fresh fruit, vegetable, and whole grain offerings and education opportunities as part of the 2008 Farm Bill,36 support im provements in the nutritional well-being of children during the school day. Together, these initiatives enhance food offerings provided to schoolchildren through the USDA NSLP pro grams and offer opportunities for children to be socialized into healthy eating habits. The prom inent role school programming can and will play in addressing the childhood obesity crisis and its attendant implications on health and academic achievement cannot be discounted. Because HOPS was a school-based preven tion intervention, eating and exercise habits outside of school (including extended periods of out-of-school time, such as holidays and summer vacation) could not be controlled, thus perhaps affecting the internal validity of the study. However, because the sample included only children who qualified for the free and reduced-price meals program of the NSLP, a high proportion of the children can be expected to have consumed multiple meals each day at school. Additional methodologic limitations included that the study population April 2010, Vol 100, No. 4 | American Journal of Public Health Hollar et al. | Peer Reviewed | Research and Practice | 651 was not selected at random, that there was limited geographic variability, and that only 1 school served as a control. Also, although the intervention involved nutrition and healthy lifestyle curricula and physical activity compo nents, the design did not include assessment of intervention exposures (such as minutes of the curricula used). Last, there has been con siderable debate about the validity of stan dardized tests, such as the FCAT, in ade quately measuring academic achievement, particularly among minorities.37–39 The strengths of this pilot study were the large sample size (over 1100 children), the diversity of the sample (high minority repre sentation), multiple measures of the same group over an extended time period (2 years), and the analysis of a homogeneous socioeco nomic status group (free or reduced-priced meals in the USDA NSLP participation as proxy), thus adhering to intervention fidelity and improving internal validity. These pilot data argue for a large-scale, randomized, mul ticenter study similar to the one presented here to improve external validity. School-based obesity prevention interven tions that include changes to school-provided meals, nutrition and healthy lifestyle education, and physical activity components show prom ise in improving health and academic perfor mance, particularly among elementary-aged children from low-income backgrounds. These findings are particularly encouraging given that many children from low-income backgrounds receive a significant proportion of their daily nutrition requirements at school. j About the Authors Danielle Hollar is with the Department of Medicine, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, and Agatston Research Foundation, Miami Beach, FL. Sarah E. Messiah is with the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Clinical Research, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Gabriela Lopez-Mitnik is also with the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Clinical Research, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. T. Lucas Hollar is with the Department of Government, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, TX. Marie Almon is with South Beach Preventive Cardiology, Miami Beach, FL. Arthur S. Agatston is with the Agatston Research Foundation, Miami Beach, FL. Correspondence should be sent to Danielle Hollar, PhD, MHA, MS, 881 NE 72nd Terrace, Miami, FL 33138 (e-mail: daniellehollar@gmail.com). Reprints can be or dered at https://www.ajph.org by clicking the ‘‘Reprints/ Eprints’’ link. This article was accepted August 11, 2009.

RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

Contributors D. Hollar originated the study and supervised all aspects of its implementation, assisted with data collection and analyses, and led the writing of the article. S.E. Messiah led the analyses and assisted with the writing of the article. G. Lopez-Mitnik analyzed data. T. L. Hollar assisted with data collection and analyses and writing of the article. M. Almon provided technical assistance for dietary intervention implementation. A. S. Agatston reviewed the article. Acknowledgments All aspects of this research were funded by the Agatston Research Foundation. The authors thank the following colleagues for their ongoing advice and help with the Healthier Options for Public School Children (HOPS) Study: David Ludwig; Michelle Lombardo, Karen McNamara, and The Organ Wise Guys staff; Melanie Fox; Caitlin Heitz; colleagues at the US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service; HOPS partners in Miami, FL (private schools); Osceola and St. Johns Counties, FL; Harrison, MS; Batavia; IL; Evansville, IN; New Hanover, NC; Buffalo and Chenango, NY; Brooke and Fayette Counties, WV; generous donors to the Agatston Research Foundation; and especially the HOPS partners at the school district of Osceola County, FL, where the interventions for which the results are presented here were conducted. We also express our ongoing gratefulness to the children who participated in our study. The lead author had full access to the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Human Participant Protection The Sterling institutional review board, Atlanta, GA, approved the study. Letters were sent home to the parents of students attending the 6 study schools. Parents signed consents for their minor children if they did not want their child to participate. References 1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. 2. Institute of Medicine. Preventing Childhood Obesity. Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: National Acad emy Press; 2004. 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/ 07newsreleases/obesity.htm. Accessed November 9, 2008. 4. Ford ES, Chaoyang L. Defining the metabolic syn drome in children and adolescents: will the real definition please stand up? J Pediatr. 2008;152( 2):160–164. 5. Cook S, Auinger P, Li C, Ford ES. Metabolic syndrome rates in United States adolescents, from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2002. J Pediatr. 2008;152(2):165–170 Epub 2007 Oct 22. 6. National Institutes of Health. The Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cho lesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2001. NIH publication 01-3670. 7. Vanhala M, Vanhala P, Kumpusalo E, Halonen P, Takala J. Relation between obesity from childhood to adulthood and the metabolic syndrome: population based study. BMJ. 1998;317(7154):319. 8. Guo SS, Roche AF, Chumlea WC, Gardner JD, Siervogel RM. The predictive value of childhood body mass index values for overweight at 35 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59(4):810–819. 9. Zametkin AJ, Zoon CK, Klein HW, Munson S. Psychiatric aspects of child and adolescent obesity: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(2):134–150. 10. Vila G, Zipper E, Dabbas M, et al. Mental disorders in obese children and adolescents. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):387–394. 11. Taras H, Potts-Datema W. Obesity and student performance at school. J Sch Health. 2005;75(8):291– 295. 12. Mustillo S, Worthman C, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. Obesity and psychiatric disorder: developmental trajectories. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 pt 1):851–859. 13. Halterman JS, Kaczorowski JM, Aligne CA, Auinger P, Szilagyi PG. Iron deficiency and cognitive achievement among school-aged children and adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1381–1386. 14. Kleinman RE, Hall S, Green H, et al. Diet, breakfast, and academic performance in children. Ann Nutr Metab. 2002;46(suppl 1):24–30. 15. Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA Jr. Food in sufficiency and American school-aged children’s cogni tive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):44–53. 16. Murphy JM, Wehler CA, Pagano ME, Little M, Kleinman RE, Jellinek MS. Relationship between hunger and psychosocial functioning in low-income American children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998; 37(2):163–170. 17. Woodward-Lopez G, Ikeda J, Crawford P. Improving Children’s Academic Performance, Health and Quality of Life: A Top Policy Commitment in Response to Children’s Obesity and Health Crisis in California. The Center for Weight and Health College of Natural Resources, Uni versity of California, Berkeley. Available at: https:// nature.berkeley.edu/cwh/PDFs/CewaerPaper_ Research.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2008. 18. Datar A, Sturm R. Childhood overweight and ele mentary school outcomes. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006; 30(9):1449–1460. 19. Datar A, Strum R, Magnabosco JL. Childhood over weight and academic performance: national study of kindergartners and first-graders. Obes Res. 2004;12(1): 58–68. 20. Li X. A study of intelligence and personality in children with simple obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19(5):355–357. 21. Mo-suwan L, Lebel L, Puetpaiboon A, Junjana C. School performance and weight status of children and young adolescents in a transitional society in Thailand. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(3):272–277. 22. Briefel RR, Wilson A, Gleason PM. Consumption of low-nutrient, energy-dense foods and beverages at school, home, and other locations among school lunch 652 | Research and Practice | Peer Reviewed | Hollar et al. American Journal of Public Health | April 2010, Vol 100, No. 4 participants and nonparticipants. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2 suppl):S79–S90. 23. Almon M, Gonzalez J, Agatston AS, Hollar TL, Hollar D. The HOPS Study: dietary component and nutritional analyses. Poster presented at: Annual Nutrition Confer ence of the School Nutrition Association; July 17, 2006; Los Angeles, CA. 24. Almon M, Gonzalez J, Agatston AS, Hollar TL, Hollar D. The dietary intervention of the Healthier Options for Public Schoolchildren Study: A school-based holistic nutrition and healthy lifestyle management program for elementary-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006; 106(8):A53. 25. Gonzalez J, Almon M, Agatston A, Hollar D. The continuation and expansion of dietary interventions of the Healthier Options for Public Schoolchildren Study: a school-based holistic nutrition and healthy lifestyle management program for elementary-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(suppl 3):A76. 26. Florida House Bill CS/CS/HB 967—Physical Edu cation. Available at: https://www.myfloridahouse.gov/ Sections/Bills/billsdetail.aspx?BillId=35827. Accessed July 20, 2009. 27. ILSI Research Foundation. Delta H.O.P.E. Tri-State Initiative. Final Report to the Mississippi Alliance for Self Sufficiency for the period: August 2003 to June 2007. Washington, DC: International Life Sciences Institute. 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Body mass index percentiles for children. Available at: https:// apps.nccd.cdc.gov/dnpabmi. Accessed February 22, 2009. 29. Achievement Levels FCAT. Available at: https:// fcat.fldoe.org/fcatpub3.asp. Accessed February 6, 2009. 30. US Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition Service. National School Lunch Program Fact Sheet. Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/Lunch/ AboutLunch/NSLPFactSheet.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2009. 31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Clinical growth charts. Avail able at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/growthcharts/ clinical_charts.htm. Accessed February 6, 2009. 32. Webber LS, Osganian SK, Feldman HA, et al. Car diovascular risk factors among children after a 2 1/2- year intervention—The CATCH Study. Prev Med. 1996;25(4):432–441. 33. Hollar D, Messiah SE, Lopez-Mitnik G, Hollar TL, Agatston AS. Effect of a school-based obesity prevention intervention on weight and blood pressure in 6–13 year olds. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(2):261–267. 34. Shephard RJ. Curricular physical activity and aca demic performance. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 1997;9(2):113– 126. 35. Dwyer T, Sallis JF, Blizzard L, Lazarus R, Dean K. Relation of academic performance to physical activity and fitness in children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2001;13:225– 237. 36. Food, Conservation and Energy Act of 2008, HR 2419, 110th Cong. Available at: https://www.govtrack.us/ congress/billtext.xpd?bill=h110-2419. Accessed July 20, 2009. 37. Linn RL. A century of standardized testing: contro versies and pendulum swings. Educ Assess. 2001;7(1): 29–38.

RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

38. Kubiszyn T, Borich G. Educational Testing and Measurement: Classroom Application and Practice. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2007. 39. Perrone V. Association for Childhood Education international position paper on standardized testing. 1991. Available at: https://www.acei.org/onstandard. htm#question. Accessed July 20, 2009. April 2010, Vol 100, No. 4 | American Journal of Public Health Hollar et al. | Peer Reviewed | Research and Practice | 653 Copyright of American Journal of Public Health is the property of American Public Health Association and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Introductionn

Through a survey that was conducted by the Ministry of Health and Population in 2014, it was noted that 92% of women aged between 15 and 49 who were presently or formerly married had undergone FGM. Though this survey noted that between the periods of 2005 to 2014 the number of women who underwent FGM had reduced, about 56% of girls below the age of 19 years were still expected to undergo the harmful traditional practice (Coyne & Coyne, 2014).

Differences between two selected articles

Critiquing the articles

Egypt is a highly medicalised country or rather it has a well-developed medical practice of which the participation of medical doctors in practice has dampened the progress of eradicating the harmful traditional practice. The survey mentioned above also noted that certified medical doctors performed 82% of FGM and this greatly creates the presumption that it is a safe traditional practice (Coyne & Coyne, 2014)

In 2008, Egypt national government through parliament passed through laws, which illegalized FGM. However, majority of the population have not adhered to these laws and they bash it for being contradictory to their beliefs and traditional practices (Serour, 2013). This is agitated by the fact that the society perceives the uncircumcised females to be ill-mannered and bad-behaved in nature and most of the time been shunted out, forcing the majority of a parent to conform to the pressure citing that they want the best for their children. The tradition aspect of the FGM is a rite of passage to womanhood. In most parts of the country, FGM has a major backing from Imams and other religious decors, although this is in longer the case but there still those who have the same mentality (Østebø & Østebø, 2014).

Theoretical Concept

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is a harmful traditional practice with severe health complications. FGM primarily involves removing partial or all external woman genital organs thereby causing injury to female genitalia for no apparent medical reasons. According to World Health Organization (2008), FGM has no known or documented medical benefits. On the contrary, its physical and psychological consequences are harmful to the victims. The removal of normally functional body parts interferes with the normal functionality of the organ especially during childbirth that many led to complication, infant or maternal death (Pacho, 2015). Although, the practice was largely undertaken by communities traditionally, it is against social work values that advocates for mutual engagement of all society members (Children, girls, boys, men, and women)

The practice is wildly condemned internationally as discriminatory and it is considered as violence against girl child and women due to serious health concerns, the pain it causes, and risk involved. In the study by Kaplan et al. (2011) on the health consequences of FGM in Gambia, majority of women who underwent the operation report cases of complication, infections, psychological trauma, and even death, during or after the procedure regardless of the type of FGM operation. Despite its grievous consequences, the practice is still deeply rooted in developing nation especially in Africa (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016).

In a study by Kaplan-Marcusan et al., (2009), it noted that the problem of FGM persist in the mostly in primary care centers with increasing cases documented by the professionals (Pediatrics and gynecologist), tripling in the three year time period. World Health Organization (WHO) (2015) estimate that about 100-140 million girls and women have undergone FGM worldwide with an additional two million at risk of the same yearly, while 3.6 million are affected directly and indirectly by it (UNICEF, 2013). Unfortunately, traditional healers who do not have medical education/qualification or experience in performing surgical operations are the leading culprits in performing FGM. However, Kaplan-Marcusan et al, (2009) indicated that nations such as Egypt, Sudan, and Kenya have high number of medical personnel performing the procedure, 61%, 36%, and 34% of the total FGM reported respectively. FGM is continuously practiced by communities in these three countries due to various reasons of which the most common is the fact that is perceived to safeguard against premarital sex and as resultant, it preserves morality through prevention of female promiscuity (Yirga et al. 2012). According to Yirga et al. (2012), in Kenya and Nigeria, 30 and 36 percentages of women respectively agrees with the above-misconstrued claim. On the other hand, 51 percent of Egyptian women believe that FGM prevents adultery, while 33.4 percent of the subject attributed the practice to important religious traditions (WHO, 2008).

A brief history of FGM in Egypt

Female ‘circumcision’ has been practiced in Egypt for centuries with many historians citing its origin there (Ofor & Ofole, 2015). In the study by Pacho (2015), he stated that the most radical practice of FGM was performed nearly 2500 years ago (by examining of Egyptian mummies), which means it began before the development of Islam or Christianity. The practices gained popularity in the 1970s with majority advocating for it while human right organization voiced against the practice and calling for it abolition (Pacho, 2015). In the same period, the concept of female genital mutilation was coined to establish the gravity of the act on the victims and its violation of girls and women rights.

Before 2008, FGM procedures were legal in Egypt and hence performed by qualified doctors in Hospitals. Although, the law later banned its practice, the prevalence of the practice remains high, with an increase in proportion of operation performed by traditional healers (Refaat, 2009). In 1994, Egypt’s ministry of Health permitted government doctors to perform FGM terming it as effort to promote and monitor safe procedure, despite the ban of decree after Human rights criticizing it, some hospitals (Private hospital) offer alternative procedure (Shell-Duncan, 2001). It was after the publicized death of an 11-year old girl in 2007 during the operation that the government subsequently barred and restricted any licensed medical staff and hospital from FGM operation and even contributed to the enactment of laws barring FGM. (Guilbert, 2016) As a resultant of this restriction and illegalization, the practice has gone underground mostly performed by unlicensed mid-wives under the authorization of the girl’s parents (Rasheed, 2011). However, there are still cases where licensed practitioners performing the procedure have been reported (Andro & Lesclingand, 2016).

Psychoanalytic Theories

In most cases, females undergo the genital mutilation at a very tender age, between ages 3 to 15 years. Occasionally, women in their adulthood are equally subjected to the same harmful traditional practice if they had not undergone during their childhood. Sigmund Freud in his theory of psychoanalytic emphasized on the importance and significance of childhood events and experience for every child (Cherry, 2016). Therefore, the psychological impact of mutilation on a

girl child is permanent, and it has the possibility of affecting her academic and social life in the long term. Erikson in his theory of stages of psychosocial development asserted that that every person’s stage of life, experiences, and events faced determines the kind of life that one will live. According to Erikson’s theory, at a tender age in particular, six to fifteen years, the experiences encountered will greatly influence the social and economic outcome of the individual (Erikson and Joan, 1997).

Prevailing Factors That Enable the Continued Practice of FGM in Egypt

Social aspect

The arguments on FGM practices have been controversial since the late 1970s because it conflicts with some of the most basic human rights, traditional, and religious values. Blanket presumption that perpetrators of the violence have been emotionally deprived or abused in the same way during their childhood, being victims of FGM, confers that most parents, guardians and midwives will perpetrate the same deeds done onto them themselves (Boyden et al., 2012). In the Egyptian culture, the practice has been conducted dating back several millenniums (24 BC) with every female generation undergoing the procedure (Hoffman, 2013

In the same perspective, parenting norms arise from the social values within the community. Girls’ circumcision (FGM), in traditional African society is a norm, and a condition to womanhood and marriage hence perceived ‘appropriate’ necessity for those conditions (Kaplan et al., 2011). In the same context, the Egyptian parents perform the harmful traditional practice in accordance to the ways things were with no regard to the modern scientific facts. In fact, in Egypt, there is a substantial social pressure for everyone especially the parent to conform to the social norm stating that female circumcision is a normal practice (Rossem, 2016).

Economic Valuation

Traditionally, social acceptance of uncircumcised girl is very low. The communities consider them adulterous, immature and ‘children’ regardless of age (Monagan, 2010). Many believe that by having this harmful traditional procedure, it reduces sexual desires which eventually reduces the number of sexual partners hence reduces likelihood transmission of sexually transmitted disease (STDs). Furthermore, many believe that traditional education taught during this practice enhances the honor and behavior of the woman (Zaki, 2016). Monagan (2010) in his writing stated that feminine sexuality could bring shame and dishonor unto the family. In the social context, the parents who refuse to perform this practice are also shunt out of the community as their daughter are perceived to represent dishonor to the entire community.

Economic aspect

In certain Egypt communities, especially those in rural areas that are poverty-stricken the family economic survival depend on bride price paid during marriage (mostly early marriage). Generally, following the social norms, FGM practices as an imperative means to make a girl grow to a woman favorably respected by the society therefore making her, or rather, increasing her marriage ‘market value’/ payable bride price (Yirga, 2012). Therefore, it is upon the family to ‘protect’ and conserve the girls’ purity from social and physical risks of immature and extramarital sexual intercourse and abortion (Kingsley, 2016). This, in the parents’ perspective, necessitates the harmful traditional practice to curb loss of virginity by girl more so when a bride price was already paid in advance when the girl was young.

Political Aspect

The political structure and system in Egypt limits access or influence of woman on the political sphere. The extremely low representation of women and their influence results in lack reenactment of laws that are discriminatory and against the interest of women and girls, or passing legislation that protect their values and virtues (Darwish, 2014). For instance, the FGM was allowed by the government and permitted to be performed in public hospital in the early 1990s. In addition, the recent political unrest have overshadowed many Egypt social problems including FGM. The issue of FGM has been marginalized, according to Vivian Fouad, the head of the capacity building and communications department at Egypt’s National Population Council (NPC) that champions the campaign against FGM (Darwish, 2014). Furthermore, the instability has led to 75 percent reduction in FGM-related donor funds from the government and slow progress in official effort in curbing the issue (Sharma, 2011).

Moreover, the rise Muslim Brotherhood is feared by many as a potential obstacle in eradicating the practice since the group greatly agitates for Islamic laws, which do not condone the vice (Hoffman, 2011). Saad El Katani, as the leader of the Brotherhood movement/ group was once quoted stating that Islam does forbid circumcision. However, many members of the party initially argued in support of the ban on FGM but they do not speaking against the practice resulting to dormant legislation (Sharma, 2011).

Legal aspects

In 2008, FGM practices were criminalized. Since then, the government have partnered with NGOs in the fight to eradicate the practice. Despite this, there has been slow improvement in the incidence rate due to lag in enforcement of the law (Rasheed, 2011). Since the enactment of the law in 2008, prohibiting FGM with punishment ranging from two months to two years imprisonment of El-Bataa’s (father a 13 year old girl who died after being subjected to an FGM) and the operating doctor in 2013 was the first time anyone has been charged with FGM-related cases (Darwish, 2014).

Past Policies and Intervention

Conclusion

Various mechanisms have be deployed to curb the menace particularly in Egypt. Despite the ban and criminalization of the practices in most of countries including Egypt and Kenya, eradicating the practice is termed problematic by many scholars as the problem is undertaken by the society secretly and out of the public glare (Hoffman, 2013). Most countries have strict laws against the practice. For example, in Spain, parents found guilty of practicing FGM faces six to twelve years in prison and girls are taken care by the social services (Kaplan-Marcusan, 2009).

Laws and policies that are against the vices are not sufficient to stop the vice neither is offering refuge nor prosecuting the people performing these atrocities also enough to stop the harmful traditional practice. This is because traditional and religious beliefs are the bases of its continued practices. Therefore, engaging Government agencies, Non- Government Organizations (NGOs) and Internationals Organization such as WHO, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF, the UN Population Fund, UN Women, the European Union (EU), the National Population Council and other the major corporation over the years without solving the people’s beliefs have seen a disappointing gradual reduction of FGM practices. Of which the gradaual reduction is linked with strict limitation of medical practitioners in engaging in the practice (WHO, 2014).

Eradicating the practice in totality highly relies on the level awareness and education about the outdated traditional practice and its harmful effect. Recently, for instance, adoption of more inclusive approach that entails incorporating communities into the fight against the harmful traditional practice has shown a slight decrease in the case of FGM in Egypt (Lee-Johnson, 2015). For example, in Kenya, the Kenya Women Parliamentary Association in support of UNICEF is reaching out to the communities through education on the consequences of FGM and Human rights violation. According to Kaplan-Marcusan et al. (2009), developing a positive and inclusive intervention models such as campaigning for human rights, offering protection and legal services to the victims and empowering them with education and skill, will result in linkage of this health problem to other cultural beliefs and values that in long run projects a success in combating this menace.

Trends of FGM over the years in Egypt

FGM in Egypt is reported to affect 90-97 percent of women, though the number of women undergoing the procedure dropped considerably since 2014, six in every ten down from nine in every ten in 2008 (Zaki, 2016). Although the 2008 legislation prohibits medical practitioners from performing the practice, a study by Rashid et al. (2011) found that the incidence remained relative high. Furthermore, the study showed that most procedure are performed by general practitioners.

Although there are four types of FGM varying with the procedure and depth of the cut, namely Type I (Clitoridectomy, involves partial or total removal of clitoris). Type II (Excision entails removing clitoris and labia partially or totally). Type III (Infibulation, this is most severe involving narrowing the vagina opening without removing clitoris). Lastly, Type IV, (this mainly involves all other procedure to genitalia such as pricking, piercing, incising and cauterization). However, the most common type of FGM procedure practiced in Egypt is Type I, II and III, which are occasionally performed by doctors (Refaat, 2009).

As stated earlier, According to the Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (EHDS) (2014), 92 percent of married and formally married women between the age of 15 and 49 years are genitally mutilated. However, 87 percent women between 20 and 24 years and 95 percent of their counterpart between 35 and 49 years are reportedly circumcised. Most studies confirm a 10 percent difference in prevalence of FGM among girls between the age of 10 to 19 years and their mothers, showing a declining FGM practice (Rossem et al., 2016).

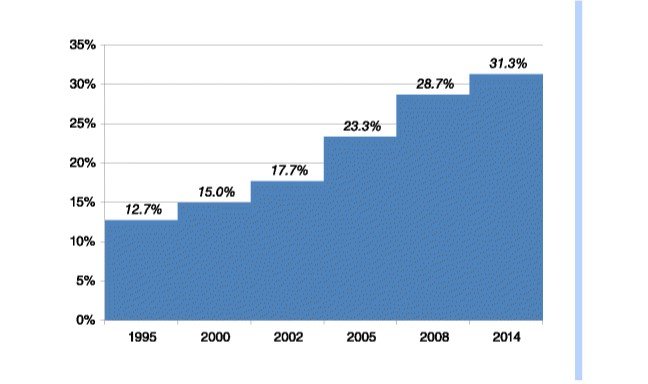

According to EDHS (2014) data, the people opposing the FGM increased in the year between 1995 and 2014. In 1995, only 13 percent of ever-married women were against the FGM but by 2014, the number had increased to 31 percent. This is illustrated the image below.

Figure 1: Trends of FGM opposition among ever-married Egyptian women Source: Rossem et al., 2016)

Possible solutions that Development Agencies can adopt to Curb FGM in Egypt

The FGM practice tends to be complex and problematic when dealing with it more so in the case of Egypt where medical practitioners also participate in the harmful traditional practice. As stated earlier, this vice is associated with both traditional, religious and patriarchy aspects of the society, which have collectively made combative measures to be unsuccessful over the years in Egypt. Laws, policies, and interventions are ineffective in the total eradication of FGM inEgypt unless local context is amicably understood. The punitive laws and measures only pushes the practice underground to the underground scene, subsequently presenting more severe consequences to the health and life of the females. The need to understand why and what drives the communities to practicing female mutilation is of great importance in curbing this menace (Darwish, 2014). Basing on traditional perspective, it is not about stiffening the law but rather addressing people’s mindset on the FGM practice, which is the key to changing the social belief and attitude. In Kenya, for instance, though the practice is not completely eradicated, inclusion of parliamentary women members, influential athletes, and communal leaders has seen drastic fall in the FGM case (Cloward, 2015). The societies are educated on the negative consequence, adultery notion, STDs prevention mechanism and alternative means of educating the girls to grow to respectable persons in the society, such as taking their modern education serious and foregoing the notion of ‘honorable’ wife in the society (Cloward, 2015). Therefore, engaging with vulnerable girls and their parents in endangered communities helps to understand the drivers of FGM and possible measures in dealing with the problem. Mostly, laws are made without consolation with the local communities especially the girls. The social acceptance and experience of the uncut girls may cause majority to engage voluntarily in the practice (Kingsley, 2016). It is observed that, girls make decisions on basis of their social assessment of their future adult chances and lives; whereas parents do, what they think is in the best interest for their children. Therefore, effective strategies is for development agencies to first gain an understanding on the Egyptian culture and thereafter, formulate a comprehensive educational programme targeting mostly those living in rural areas and lower class areas in order to debunk the myths associated with the benefits of FGM and even educate them on the risks.

Conclusion

Child as symbol of innocence juxtaposed to adults’ world of chaos and lack of morals and values Conferring rights not only onto girls but also women transforms them to recognizing their moral equalities with men in the society and therefore underscoring universal moral worth of all human beings (Diptee, 2013).. Moreover, the women particularly girls need to be treated as rights holder and those rights need to be advocated on their behalf by communities and developmental agencies. The perceived concept of ‘stolen childhood’ ignores the reality that child’s social experiences does not deviate away from values and conditions conferred to them by the society in general (Diptee, 2013).

The concept of FGM arguably disregards the basic human rights particularly the girl-child. The traditional notion of preparing the girl to womanhood and curb adultery through ‘circumcision’ is outdated. As discussed, FGM is entwined with many complexities varying between traditional and religious aspect of the society particular in Egyptian society. Therefore, legislative laws prohibiting the practice are not an effective solution but rather understanding the roots and its bases then combating those drives is the key to succeeding in the fight. Finally, it is imperative for development agencies to engage more with the communities and changing their mindset not only the parent, guardians, society member but also the girl-child is a major key step towards combatting the issue of FGM in Egypt.

Continue your exploration of Remain Such a Persistent Issue In Us Politics with our related content.

References

Andro, A., & Lesclingand, M. (2016). Female genital mutilation. overview and current knowledge. Population, 71(2), 216-296.

Coyne, C. J., & Coyne, R. L. (2014). The Identity Economics Of Female Genital Mutilation. The Journal of Developing Areas, 48(2), 137-152

Darwish, P. (2014). FGM eradication in Egypt since 2011: A forgotten cause? - Politics - Egypt - Ahram Online. English.ahram.org.eg. Retrieved 6 March 2017, from https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/97618/Egypt/Politics-/FGM-eradication-in-Egypt-since--A-forgotten-cause.aspx

Diptee, A. (2013). Stolen Childhood: Slave Youth in Nineteenth Century America. Slavery & Abolition, 34(1), 191-193.

Egyptian government supports medicalisation of female genital mutilation. (1995). Reproductive Health Matters, 3(5), 134.

Erikson. Erik H. and Joan M. (1997) The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version. New York: W. W. Norton

Guilbert, K. (2016) Death of Teenage Girl Casts Doubt on Egypt’s Efforts to End FGM: Activities. Reuters [online] retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-egypt-fgm-idUSKCN0YM287 [accessed 5 March 2017]

Hoffmann, N. (2013). Female Genital Mutilation in Egypt. Global Journal Of Medicine And Public Health, 2(3).

Kaplan, A., Hechavarría, S., Martín, M., & Bonhoure, I. (2011). Health consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting in the Gambia, evidence into action. Reproductive Health, 8(1).

Kaplan-Marcusan, A., Torán-Monserrat, P., Moreno-Navarro, J., Fàbregas, M., & Muñoz-Ortiz, L. (2009). Perception of primary health professionals about Female Genital Mutilation: from healthcare to intercultural competence. BMC Health Services Research, 9(1)

Kingsley, P. (2017). In Egypt, social pressure means FGM is still the norm. the Guardian. Retrieved 4 March 2017, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/06/female-genital-mutilation-egypt

Monagan, S. (2010). Patriarchy: Perpetuating the Practice of Female Genital Mutilation. Journal Of Alternative Perspectives In The Social Sciences, 2(1), 161-181.

Østebø, M. T., & Østebø, T. (2014). Are religious leaders a magic bullet for Social/Societal change? A critical look at anti-FGM interventions in ethiopia. Africa Today, 60(3), 82-101,152-153.

Pacho, T. (2015). Complexity of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting. Journal Of Social Work Values And Ethics, 12(2), 63-75.

Rasheed, S., Abd-Ellah, A., & Yousef, F. (2011). Female genital mutilation in Upper Egypt in the new millennium. International Journal Of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 114(1), 47-50.

Refaat, F. (2009). Medicalization of female genital cutting in Egypt. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 15(6), 1379-88.

Serour, G. (2013). Medicalization of female genital mutilation/cutting. African Journal Of Urology, 19(3), 145-149.

Sharma, B. (2011). For Young Women, a Horrifying Consequence of Mubarak’s Overthrow. New Republic. Retrieved 6 March 2017, from https://newrepublic.com/article/96555/egypt-genital-mutilation-fgm-muslim-brotherhood

Shell-Duncan, B. (2001). The medicalization of female ‘‘circumcision’’: harm reduction or promotion of a dangerous practice?. Social Science & Medicine, 52, 1013-1028.

Van Rossem, R., Meekers, D., & Gage, A. (2016). Trends in attitudes towards female genital mutilation among ever-married Egyptian women, evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys, 1995–2014: paths of change. International Journal For Equity In Health, 15(1).

World Health Organization (2008). Eliminating female genital mutilation: an interagency statement. OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO. Geneva,

Yirga, W., Nega Kassa, Mengistu Gebremichael, & Aro, A. (2012). Female genital mutilation: prevalence, perceptions and effect on women's health in Kersa district of Ethiopia. International Journal Of Women's Health, 4, 45-54.

Zaki, M. (2016). Egypt seeks tougher punishment for female genital mutilation. news.trust.org. Retrieved 6 March 2017, from https://news.trust.org/item/20160829144755-55827/

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts