Patient Confidentiality in Saudi Healthcare

Chapter One Introduction And Background To The Study

…It is crucial not only to respect the sense of privacy of a patient but also to preserve his or her confidence in the medical profession and in the health services in general. Without such protection, those in need of medical assistance may be deterred…from seeking such assistance thereby endangering their own health (and)…that of the community. The domestic law must therefore afford appropriate safeguards so that there may be no such communication or disclosure of personal health data as may be inconsistent with the guarantees of Article 8 of the Convention.

Background of the Study

This thesis examines the adequacy of the existing legal safeguards for patient confidentiality under the Saudi Arabian legal system. Patient confidentiality can be simply referred to as the patient’s right to the protection of their personal medical information within health care institutions under normal conditions. The healthcare practitioner-patient relationship becomes more complex as a result of advances in informational technology and modern forms of communication which further involves the management of patients’ records. There is an increase in the use of information technology in managing patients’ private information in the Saudi Arabian healthcare delivery systems without a corresponding review in the law, dealing with patient confidentiality. The thesis argues that, even where a patient is entitled to the right to confidentiality under the law, the law ought to be dynamic to deal with the new challenges. The quote above by the European Court of Human Rights (ECrtHR) in Z v Finland, established that where patients are assured of their rights to both confidentiality and privacy, it will result in them having confidence in medical services as well as in seeking help from the healthcare practitioners (HCPs). The contrary will mean a lack of confidence in the medical services, which will be counter-productive. In Z’s case, the court restated the need for domestic law to afford appropriate safeguards for protecting the right of the patient to confidentiality. Z applied for relief to the ECtHR alleging that, her right to privacy under Art 8 of the Convention was infringed upon when her HIV status was disclosed by the media during her husband’s criminal trial. It is important to note, from the start of this discussion, the unique nature of the Saudi Arabian legal system before a discussion on how patient confidentiality is protected under that legal system. Saudi Arabia is governed under Shari’ah law principles. Given that, the Shari’ah is a body of divine law, it is in many respects different from man-made laws. Thus, the study reviews literature from both perspectives. It is also worthy of note that there is limited literature on the subject from a Saudi Arabian standpoint. The motivation for the research is borne out of the author’s personal working experience as an HCP. The author’s job role often requires the use of social media (platforms) and electronic information systems in communicating patients’ private information. Usually, the author and other team members engage one another via social media channels during the management of outbreaks of infectious diseases. Furthermore, the research aims to contribute to the development of a model for the protection of patient confidentiality in Saudi Arabia. This study, apart from maintaining the distinction between the concepts of confidentiality and privacy, focuses on the right to confidentiality, as opposed to an elaboration on the right to privacy. Thus, the study unties the knot around data protection/ confidentiality under the Saudi Arabia legal system vis-à-vis international best practice as exemplified in the system applicable in Europe. The study is, however, not a comparative research.

1.2 Research Questions and Objectives

Information technology (IT) revolution has improved the quality of medical care in many countries. Nevertheless, the increase in the use of modern information technologies in the care of patients around the globe presents a threat to the safety of patients’ private information. Therefore, this research addresses the overarching question: How adequate is the legal protection for managing patient confidentiality under the Saudi Arabian legal system? In order to tackle the above question, the study reviews human rights in patient care (especially as it relates to the right to patient confidentiality) and how this has been defined under the international human rights laws (IHRLs) and at the same time, it examines the legal framework for the protection of patient confidentiality in Saudi Arabia. The research aims to improve on the current framework for the protection of patients’ right to confidentiality in Saudi Arabia and to design a model that will be dynamic in the face of contemporary challenges to patient confidentiality, as a result of an increase in the use of information technology in the management of patients’ private data. For achieving this aim, the study identifies the following objectives:

Take a deeper dive into Confidentiality Concerns in Response to Client's Phone Call with our additional resources.

To define what is meant by patient confidentiality and how it is protected by law;

To examine what lessons may be learnt from the IHRLs in so far as this is not incompatible with the Shari’ah;

To determine whether the current Saudi Arabian laws offer adequate protection for patient confidentiality in compliance with the triple test of legality, legitimate aim and proportionality;

To identify current challenges that impair the adequacy of legal protection for patient confidentiality and to identify gaps in the laws; and

To advance appropriate recommendations geared towards improving the protection for patients’ right to confidentiality in Saudi Arabia.

In pursuing these objectives, this study argues in support of a liberal interpretation of Islamic principles to advance the right to patient confidentiality.

1.3 The Contextual Framework

The Shari’ah, which regulates Saudi Arabia, is derived from the Islamic tradition. It ‘indicates the moral code and religious law of a prophetic religion…Shari’ah is all-embracing where it embodies acts of devotion (ibadah), commercial transactions (mu’amalah), political system (siasah), marriage or family laws (munakahat) as well as the concepts of offences, crimes…’ The Shari’ah places a high premium on and protects an individual’s right to confidentiality as well as privacy with a few exceptions. Furthermore, there are several regulatory protections for personal data that are spread across different legislations. Recent advances in IT and the use of social media platforms have opened up a new vista in the management of patients’ confidential information not only on the globe but also in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In the same vein, the use of the internet among HCPs is on the increase. For instance, available statistics show that as of 2018, internet users in Saudi Arabia are around 30.25 million with about 25 million active social media users. Furthermore, out of the nearly 25 million persons those are active on social media, 18 million Saudis access social media platforms on their mobile devices. This number accounts for nearly 72 per cent of all social media users in the country. In the same vein, there is increasing use of smartphones with internet capability among HCPs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. For instance, in a study on medical interns and final year medical students conducted at the Qassim University, Saudi Arabia, it was revealed that all 100 per cent of the participants own smartphones. However, 78 per cent of the participants claimed that they had never used their smartphones to share patient-identifiable data with colleagues (which carry a risk to patient’s confidentiality as well as privacy). Another study of mobile phone use among medical residents in Saudi Arabia, using a cross-sectional multicentre survey, showed that, 99 per cent of the participants were mobile phone users with no significant difference in use between male and female respondents. Aside the potential risk to breach of confidentiality due to the use of information technology being a global concern, the unique nature of the legal system in Saudi Arabia calls for concern due to the country’s conservative legal system. For example, in a survey conducted in the Middle East, it was reported that, the average cost of data breach in the Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) stood at $108.52 per capita. From the United Kingdom’s perspective, there have been crucial reports in the mainstream media with the headlines implicating HCPs for unprofessional conduct as a result of breaches of patient confidentiality on social media platforms. Here are a few examples: ‘Medical students’ cadaver photos get scrutiny after images show up online,’ and ‘Nursing students expelled from university after posting pictures of themselves with a human placenta on Facebook.’ Another reported HCPs abuse of social media was an incident involving five nurses who were fired for Facebook postings. Even though there is a dearth of decided cases involving breach of patient confidentiality, incidents like the ones mentioned above raise the risk of possible breaches of patient confidentiality in the care setting. This possibility is a thorny issue particularly for a jurisdiction such as Saudi Arabia. On the positive side, Saudi Arabia, despite being a conservative and culturally sensitive country, has witnessed spectacular progress in the healthcare and stands out among peers. Saudi Arabia is investing heavily in electronic healthcare information systems and aiming to build a single electronic health system in the year 2020. As a result of Saudi Arabia’s introduction of an electronic medical information system, the use of e-health involvement systems is becoming widespread.

Interestingly, patients in Saudi Arabia show increasing interest in e-health management, and are happy with the use of health information technology to manage their private data. A Saudi empirical study reveals that, nearly three-quarters of the respondents showed interest in the electronic health information system to manage their care. However, about an equal proportion (representing 67 per cent) expressed some concerns about the possibility of a data breach and they are worried for their personal health information being stored online.

1.3.1 The Healthcare Professional and Patient Relationship

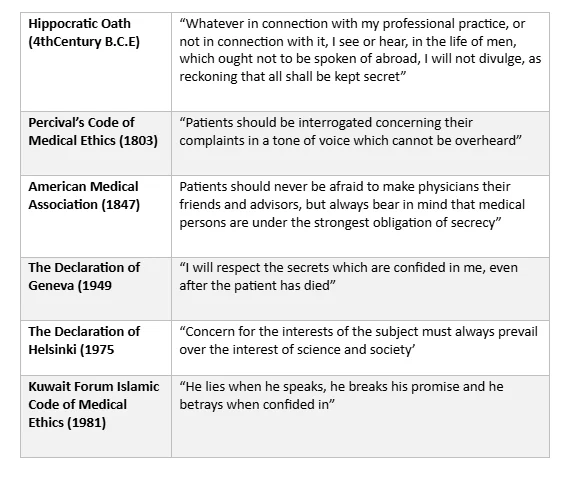

It is not out of place to discuss the relationship between a patient and the HCP in a study on patient confidentiality. The HCP-patient relationship is an ancient one and has developed over time. Apart from the expectation that the HCP must have good interpersonal skills, be a good listener, be trustful, compassionate and caring, the HCP-patient relationship is a fiduciary one and requires utmost good faith and care. It is regarded as a relationship built on the concept of trust. Whilst there is no direct provision in the Qur’an or the Sunnah that deals with confidentiality of information obtained as a result of an HCP-patient relationship, contemporary Islamic scholars have interpreted the statement of the Prophet (peace be upon him (PBUH)) ‘the one whose counsel is solicited is the bearer of Amana (trust)’ to infer a duty of trust on HCPs who, in the course of performing their roles, assume a fiduciary relationship with their patients. Thus, by analogy, anyone who is entrusted with confidential information including HCPs, lawyers, bankers and accountants is under a duty to diligently guard the information received in the course of carrying out that duty. Akin to the Hippocratic Oath, Muslim doctors are required to take an oath not to disclose anything that they see or hear in the course of their engagement with the patients. The Hippocratic Oath, now referred to as the World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Geneva, reads in part thus: ‘I will respect the secrets that are confided in me, even after the patient has died.’ The Islamic Medical Association has on its part implemented a similar oath for Muslim physicians. Therein, Muslim physicians are required to state as follows: ‘Take this oath in thy name, the Creator of all the heavens and the earth and undertake to respect the confidence and guard the secrets of all my patients’ The right to patient confidentiality further promotes trust and confidence. Trust on the part of the HCP to protect the patient and confidence on the part of the patient to be able to disclose information about their private life. Furthermore, the right to confidentiality will aid the HCP to successfully understand the patient’s ailment, diagnose it and properly plan for the right line of treatment. HCPs must bear in mind, while dealing with the patients, that ‘trust is difficult to gain and easy to lose.’ Furthermore, confidential relationships must encourage openness, trust, frank disclosure of all the possible relevant information between the patient and HCP to enable the latter to successfully treat the patient’s disease or illness. Therefore, the legal protection of patient confidentiality is of utmost importance.

1.3.2 Ethical Basis of Patient Confidentiality

Whilst it is noted that the patient’s confidentiality is a matter of culture, society and legislation, it is also a professional duty for the HCP just like other persons, who have a fiduciary responsibility. Every HCP owe an ethical duty to protect their patient’s confidential information. From a consequentialist perspective, protecting patient confidentiality could potentially maximise good consequences by creating the trust in the patient to enable that the patient make full disclosure of health information which in turn, aids the HCP for making more accurate understanding about the patient’s ailment and to recommend a suitable treatment regimen. In order to build and sustain trust, virtue ethicists agree that the patient expects that the professional would respect the patient’s expectation that the HCP would keep the patient’s private information secret. On the other hand, from a utilitarian perspective, the concept of confidentiality is to maximise its utility by encouraging the patient to open up to the HCP and seek medical assistance. Therefore, as an act of utilitarianism, it could allow for a breach of confidentiality, if doing so, it would maximise its utility or right/duty-based that the fact that it allows for weighing of individual rights. In line with the common law, this appeals to the greater good for most people i.e. where it is for the public interest. Thus, there needs to be a balance when the private right to confidentiality should be withheld in the interest of the public. HCPs, as a matter of ethics, owe their patients a duty to keep the latter’s private information confidential. Based on the above, professional associations and regulatory bodies in the healthcare industry have created professional codes to guide their members. For instance, the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties has created a Professional Code of Ethics for Healthcare Professions. This code echoes the need to protect the patient confidentiality. In the same vein, in the UK, the General Medical Council and the British Medical Association have published core guidance outlining the professional and ethical obligations of the doctors to maintain both confidentiality and privacy of their patients in the care setting.

1.3.3 Legal Basis of Patient Confidentiality

The duty of an HCP to maintain patient’s confidentiality apart from being an ethical one is also a legal obligation. In an empirical study conducted in Saudi Arabia, a 26-item questionnaire was developed using the Patients’ Bill of Rights and Responsibilities. The questionnaire covered among others, demographic details, educational level, as well as questions regarding patients’ awareness, perception of availability and implementation of patients’ rights including the right to confidentiality. The results showed that, while majority of the patients were concerned of their rights, they rarely exercised their rights as patients. Under the Saudi law, any liability arising from breaches of confidentiality falls within the scope of legal liability. As a general rule, HCPs in Saudi Arabia are under a legal duty to respect confidentiality of their patients. If a patient’s private information is wrongfully disclosed and doing so causes some type of harm to the patient, they could have a cause of action against the healthcare provider for the issue of breach of confidentiality or other related torts. In other western jurisdictions, e.g., the UK, the right to confidentiality could arise as a result of the constitutional protection of privacy and confidentiality. It could as well arise as a tortious liability or a breach of legislation governing patient confidentiality rights. For example, under the common law, wrongful disclosure of confidential information could constitute a legal wrong. It could directly result a breach of contract, negligence, an equitable wrong or even a criminal offence. There is, in the same vein, a possibility of a breach of human rights or a professional code of practice. Where the physician-patient relationship is contractual, an implied term of the agreement is that the physician will maintain the confidentiality of disclosures that the patient makes for diagnosis or therapy. In other instances where HCPs are paid by the healthcare institution or the government or its agency without direct contractual ties with the patients, they may still owe an implied general duty of care to the patients. Therefore, a deliberate or negligent breach may make them liable for negligence. An aggrieved patient relying on a breach of the right to confidentiality may bring an action against the HCP or the employer.

Despite the various legal frameworks, there is now a universal legal test which can be applied under the IHRLs.

1.3.4. To Share or Not to Share? The Dilemma of the HCP

HCPs may find themselves in some situations entangled in a dilemma of whether or not to disclose a patient’s private information to others, who may not be involved directly in that patient’s care. Therefore, the duty of maintaining the patient’s confidentiality may conflict with the duty to inform a critical member of the health team for the continuum care to be effectively maintained. Under international human rights law, there is an imposed duty of confidentiality on persons responsible for handling or processing a patient’s sensitive information. The responsible person and those involved at any stage of the processing of such information are obligated to maintain the confidentiality of patients’ private data. This obligation shall remain even after ending the relationship with the data subject or with the responsible person. The right to confidentiality in Saudi Arabia is governed by the Shari’ah. Under the Shari’ah, the right to confidentiality is not absolute. The recognised exceptions include the cases in which the patient has consented to the disclosure or where doing so is in the patient’s best interest or public interest or where it is required by law or the cases in which the health of a spouse or the public is at risk, especially in the prevention of an infectious disease or crime. Contemporary Muslim jurists have based the exceptions on various juristic rules. These include ‘choosing the lesser evil or greater good is always the priority,’ and the notion that the ‘public interest overrides individual interest.’ However, the jurists did not disclose the modus for evaluating the degree of harm nor the distinction between major and minor harm, which are relevant factors for determining the ‘rightness’ or ‘wrongness’ of a breach in confidentiality as compared to the principles of probability and the magnitude of potential harm. In a fatwa, for instance, the jurists affirmed that, a breach of confidentiality may become justifiable, if the harm of maintaining confidentiality overrides its benefits by allowing the commission of lesser evil to avoid the greater one and for an overriding public interest, which favours enduring individual harm to prevent public harm or safeguard the public interest. It is imperative to note that, there is a dearth of literature, which provides clues to show when it is enough to justify a breach of confidentiality under Islamic law vis-à-vis, what is applicable under the IHRLs. For instance, the studies such as ‘AIDS and Confidentiality,’ ‘AIDS and a Duty to Protect,’ and ‘to tell or not to Tell: breaching confidentiality with clients with HIV and AIDS’ have created a slightly different view of the issue from that of the Islamic viewpoint. Furthermore, Islamic fatwas have not explored concerns about the disclosure of genetic information to third parties, an issue that is very important in modern medicine and which has been investigated by Western researchers. Nevertheless, the IHRL creates a relevant legal bridge between the Saudi and Western legal systems.

1.3.5 Sharing Patient Information in the Healthcare Team

There is a general presumption that a patient has given implied consent for sharing confidential information among health care team members. The multidisciplinary team or ‘circle of care’ as it is called in other jurisdictions that includes the individuals and activities related to the care and treatment of a patient and covers related activities such as laboratory work and professional or case consultation with other health care providers. Therefore, sharing of patient’s information among them has become imperative to ensure a smooth and rapid transition during the continuum of care. Where a statute provides for a statutory duty to disclose otherwise confidential information under some defined circumstances or allows for disclosure, it would not constitute a breach of confidentiality if disclosure ensues in such situations. Examples of statutory authorisations include the reporting of infectious diseases, where there is a serious risk to others, stating of the underlying cause of death in a death certificate, notification of birth and deaths and reporting of alcohol consumption related road traffic accidents. Other exceptions include the interest of improving patient care or in the public interest, creating a database for surveillance and analysis of health and disease, to prevent acts of terrorism, or for apprehending or securing the prosecution or conviction of suspected criminals. Despite the multiple possible legal bases, a single framework of evaluation can be enshrined under the IHRL.

1.4 The Significance of the Study

Apart from being an offshoot of the right to privacy, patient confidentiality is an integral part of modern society. Patient confidentiality plays a pivotal role in society. There is, therefore, a need to ensure that this right to patient confidentiality is upheld in the face of the increasing use of modern forms of information technology. The use of IT systems by HCPs poses a challenge to the protection offered by laws in conservative jurisdictions. The case of Saudi Arabia calls more for concern considering the nature of its unique legal system. Whereas the legal protection for patient confidentiality is robust and more elaborate in the West, there is a need to investigate how modern technology may affect patient confidentiality in a legal system such as Saudi Arabia’s as well as to offer recommendations. In Saudi Arabia, a breach of confidentiality is only a criminal offence. This is in contradistinction with what is applicable in other legal systems where a breach of patient confidentiality gives rise to both a criminal offence and a tortious liability. The literature review conducted as a part of this study that reflects the fact that, there is a dearth of legal writings on the right to patient confidentiality in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This investigation is novel and unprecedented, as there has not been any doctrinal study conducted on the subject in Saudi Arabia. This research, therefore, is an attempt at evaluating the existing legal safeguards regarding the right as well as the duty for patient confidentiality in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The study seeks to fill the gap in the literature by enriching the body of knowledge on the subject. There is currently no comprehensive law under the Saudi Arabian legal system that specifically provides for information confidentiality except some provisions scattered here and there under some legislation. Some of the legislation includes Article 40 of the Basic Law of Government which protects the privacy of communication and prohibits confiscation, delay, surveillance or eavesdropping except in cases provided by the law. In the same vein, the Telecom Act makes provision to protect information exchanged via public telecom networks. Furthermore, judicial precedents are not binding on lower courts in Saudi Arabia unlike what applies in the common law system. Thus, in Saudi Arabia, decisions reached in Saudi courts do not establish binding precedents in the Kingdom. As a result, there is no guarantee that a court below a superior court will decide a subsequent case with similar facts and issues as the previous case. This is because adjudication is strictly on a case by case basis and in line with the interpretation of the Shari’ah by the trial judge. Accordingly, Article 48 of the Basic Law of Government obliges the courts to:

…apply the rules of Shari’ah in the case that are brought before them, in accordance with the precepts contained in the Qur’an and the Sunnah, and regulations decreed by the ruler which do not contradict the Qur’an and Sunnah…

The above could potentially result in inconsistencies in the interpretation of the laws. It appears that, these impediments could significantly affect the patient’s access to justice. Other grey areas of the existing Saudi data protection laws include lack of statutory definition of the terms ‘personal data’ or ‘disclosure’. Furthermore, lack of requirement for a formal notification for registration before the processing of the data in Saudi Arabia as well as the requirement for registration before processing data in the country means that, there is no structured modality for reporting breaches of personal data under any law in the country. There is a need, therefore, to address these gaps to protect personal data in the country.

1.5 Theoretical Underpinnings

This research builds on two theories. These are the theory of human rights in patient care and the theory of human rights in Islam. These theories are briefly discussed below:

1.5. 1 Human Rights in Patient Care

Since this research considers the right to confidentiality in the patient care context, it is not out of place to consider human rights in patient care. Patient care deals with the prevention, treatment and management of illness and the preservation of physical and mental well-being through the services, offered by HCPs. Human rights in patient care refer to the ‘theoretical and practical application of general human rights principles to the patient care context.’ Human rights in patient care recognise that HCPs are important actors whose rights must be respected just as the right of the patient to receive services, which further meet with international standards set out in international and regional human rights norms and agreements. Confidentiality is crucial for patients seeking diagnosis and treatment of illnesses with which stigma is attached, such as HIV/AIDS and mental illness. From a standard point of international law, human rights in this context are two-way traffic. Furthermore, the right to privacy and confidentiality, which is the crux of this research, is provided for in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Covenants on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which are accepted by Saudi Arabia. It is noteworthy that, these rights may be violated in any of the following situations:

Patient medical information is available to all staff;

Patients are forced to disclose their medical diagnosis to their employer to obtain leave from work;

Medical examinations take place in public conditions etc.

Building on the above, this study examines how a model can be structured to consider the above grounds. The interpretation and evaluation of the international human rights as exemplified by the ‘triple test’ has been selected for this study and, emphasis is placed on lessons learnt.

1.5.2 Human Rights in Islam

Given the peculiarity of the Saudi Arabian legal system, it is pertinent to consider the concept of human rights in Islam. Human rights in Islam are derived from divinity. The concept of human rights is not exclusively a Western Concept. There are numerous verses from the Qur’an that show that Islam has come to free human beings from any bondage. In Islam, human rights simply mean the natural rights, which have been ordained by Allah (God). Man enjoys these rights for being human. These rights are granted by God and not by any legislative assembly or king. It is noteworthy that, the recognition of the inherent dignity of human beings is unambiguously corroborated by the Qur’an. However, there is a need to identify possible mechanisms within Islamic law for the realisation of the practical implementation of international human rights in the domestic forum of Muslim states that apply Shari’ah or aspects of it. This stem from the fact that, under traditional Shari’ah, the early Islamic jurists addressed issues related to human rights within the general framework of rights and duties without codifying or listing specific human rights guaranteed by the Shari’ah. It is believed that, through a liberal interpretation of the Shari’ah, it is also possible to accept the idea of managing patient confidentiality as expressed in IHRL. This is because, as Viljanen puts it succinctly: “The necessary element of development of the international human rights in any context and by any actors, whether nationally, regionally or universally, is the interpretation in light of present-day conditions and requiring the increasingly high standard in the area of the protection of human rights and fundamental liberties correspondingly and inevitably requiring greater firmness in assessing breaches of the fundamental values of democratic societies.”

1.6 Research Methodology

This section discusses the approach, adopted for this research. It describes and the ways that the rationale for choosing the method for assessing the legal protection of patient confidentiality in Saudi Arabia. Following the research question formulated for the study which is: how adequate is the legal protection for patient confidentiality under the Saudi Arabian legal system? The study adopts a desktop library approach to provide a solution to the research problem, which identifies the fact that, an increase in the use of modern information technologies puts patients’ confidential data at risk. The study primarily focuses on the protection of patient confidentiality provided under the Saudi Arabian legal system. The research evaluates these laws, regulations and policies to reach a conclusion and make recommendations. The researcher adopts a legal research style. The methodology for the research is a doctrinal approach. Legal research makes a distinction between primary and secondary sources. However, there is a distinction between primary sources of law in the West and under Islamic law. In the West, primary sources of law include legislation, court decisions, and regulations that form the basis of legal doctrine. Secondary sources, on the other hand, are works which are themselves not law but which discuss and analyse legal doctrine. Under the Shari’ah system, on the other hand, the two primary and transmitted sources of law are the Qur’an (the revealed book) and the Sunnah (sayings and deeds of the Prophet (PBUH)). The combination of the two crucial sources is seen as a link between reason and revelation. The Qur’an is considered as the most important and sacred source of Islamic law. It comprises of over 500 legal verses that explicitly set out legal rulings that should be applied by believers. The Shari’ah broadly consists of the protection of one’s life, mind, offspring, religion as well as property. It is noteworthy that only limited legal rulings stated in the Qur’an and the Sunnah have a definitive nature. The body of Islamic law is contingent upon the views of Islamic jurists or the reasoning of the jurists referred to as Usul-al-Fiqh. While the Qur’an does not make any explicit or implicit legal provisions in a majority of areas, it nonetheless helps to support the system of Shari’ah. According to the Sunni schools of Islamic jurisprudence, the secondary sources of law are the consensus of the companions of the Prophet (PBUH). These are referred to as the consensus of commentators on a unresolved point of law. It is important, therefore, to note the difference(s) between the primary sources of law under the common law for instance and the Shari’ah. Upon identifying the difference between the legal system that can be applied in Saudi Arabia and those in the West in the first chapter of this thesis, the study begins with an introduction of the unique nature of the Saudi Arabian legal system and the need for protecting patient confidentiality given the increase in the use of information technology by HCPs. A comprehensive literature review follows in the succeeding chapters to analyse the legal protection for managing patient confidentiality both from the Western and Saudi Arabian point of views. Following from the above, the ethical practice for HCPs and human rights in Islam are identified as the conceptual construct upon, which the study rests. Furthermore, consequent upon the review of the literature, the research question, aim and objectives for the research were developed. The study adopts a doctrinal method of legal research to analyse legal sources. A large number of documents derived from primary and secondary sources were also reviewed. The primary sources are made up of the Qur’an, Sunnah and statutes while the secondary sources include the consensus of Islamic jurists, textbooks, journal articles, working papers, theses, newspaper articles and reports, magazines, government publications and other materials available via online sources. The study concludes with the findings and recommendations for practice and provides direction for future studies.

1.7 Research Plan and Structure

This study is divided into seven chapters. Each of the chapters is briefly described below:

Chapter One: This is a general introduction to the research. It describes the research problem, identifies the research question, justifies the research, introduces the literature, expounds on the theoretical framework on which the substructure of the study rests. Furthermore, the chapter states about the methodology adopted for the research and describe the structure of the research. The chapter also introduces the concept of confidentiality as it relates to the HCP.

Chapter two: The second chapter of the study presents a review of the concept and practice of patient confidentiality. The chapter identifies such aspects as patient confidentiality among HCPs. It discusses patient confidentiality both from Western and the Saudi Arabian perspectives. An attempt is made to introduce the reader to the practice in other jurisdictions as well as in Saudi Arabia. The reference to patient confidentiality in Western countries is to highlight the practice in those jurisdictions. The aim is not to draw comparisons but to show to what extent lessons can be learnt from the IHRLs to justify a liberal interpretation of the rules in Saudi Arabia. The triple tests for ascertaining whether the limitation of a fundamental right is justifiable are also introduced in chapter two of this thesis.

Chapter Three: Here the study reviews the Saudi Arabian laws on patient confidentiality within the context of domestic (Islamic) regional and international human rights law. The laws are examined to uncover whether or not they measure up to the standard required for protecting patient confidentiality in contemporary times given the increasing use of IT systems in healthcare practice.

Chapter Four and Chapter Five: The fourth and fifth chapters review and assess the adequacy of Saudi Arabian laws on privacy and confidentiality and those specifically dealing with patient confidentiality respectively.

Chapter Six: The sixth chapter reviews and assesses the available ‘soft norms’, which includes the professional ethics and codes as well as administrative regulations and other controls available to ensure adequate protection of the patient’s confidential data.

Chapter Seven: This chapter of the research discusses the new challenges to the protection of patient confidentiality especially the role and influence of the new information management technologies including social media platforms and electronic health information systems.

Chapter Eight: The final chapter of the study represents a summary of the findings, observations, conclusions and recommendations.

1.8 Scope, Limitations and Challenges Encountered

This thesis focuses on the legal protection to patient confidentiality under the Saudi Arabian legal system taking into cognisance evolving developments in information technology systems. The need for the law to catch up with the fast pace of technology is the bedrock upon which this study is built. While the focus of the research is not restricted to patient confidentiality in the use of electronic information system or the use of social media platforms, the scope of the thesis is limited in certain respects. Firstly, this thesis is concerned with the patients’ confidentiality and not the patient’s right to privacy per se. In other words, this research deals with data protection as against spatial privacy rights. Secondly, although confidentiality may be addressed through the prism of legal regulation, ethical self-regulation and privacy-enhancing technology, the study is about legal protection to patient confidentiality under the Saudi Arabian legal system. It is worthy of note as well that under the Saudi Arabian law of Healthcare Professions, the Ethical Code is embedded as being a part of the law to the extent that compliance with the ethic is considered as compliance with the law. Furthermore, while this study is not a comparative study, reference to international and regional instruments (e.g., the ECHR) is made for lessons that can be learnt that is not incompatible with the tenets of the Shari’ah. Besides, the research considers other areas of law outside the scope of the research topic to advance arguments. The study is limited by the paucity of literature from the Saudi Arabian perspective. The dearth of literature is compounded by the fact that some of the available literature is written in the Arabic language. Other areas of limitation include the non-availability of judicial precedents to use for the study due to the unique legal system in Saudi Arabia.

1.9 Conclusion

This chapter encapsulates the framework of the study. It introduces the reader to the unique nature of the Saudi Arabian legal system and the patient’s right to confidentiality. It is noted that whilst the right to confidentiality is an offshoot of the right to privacy, this research deals with the right to confidentiality and does not undertake a broad approach. The chapter examines human rights in patient care as well as human rights under Islamic law, as the bedrock upon which the study builds. Some points to note from the first chapter include the fact that human rights are not exclusively Western and that human rights can be traced to divine laws as it is indisputable that Islam provides recognition for human rights as one of the tenets of faith prescribed in the Qur’an and the Sunnah. The thesis argues for a liberal interpretation of the Shari’ah principles to accommodate human rights provisions in the protection of the right to patient confidentiality. Furthermore, the unique nature of the Saudi Arabian legal system means that there are no judicial precedents to rely on for the study as well the fact that there is a paucity of literature strictly from the Saudi Arabian perspective. The writer notes particularly that the increase in the use of new forms of information technology and the advancements achieved in the use of electronic healthcare management systems vis-à-vis the right of the patient to confidentiality makes this research germane. The chapter includes the research question, the aim and objective(s) for the research, the methodology adopted for the study, the research plan and structure as well as the scope and limitations for the research. The next chapter discusses understanding patient confidentiality rights as well as tests developed under the international human rights laws for the protection of human rights.

Chapter Two Understanding Patients’ Confidentiality And The Tests For Limitation Of Human Rights

2.1 Introduction

The second chapter of this thesis appraises the concept of confidentiality and the tests for the limitation of human rights. Various aspects, including the law relating to the right to patient confidentiality, are introduced and discussed in this chapter. The chapter also discusses the tests developed under IHRL for the limitation of human rights to show what lessons can be learnt to develop a Saudi Arabian model that is compliant with the tenets of the Shari’ah. This chapter introduces the gist of the study as well as develops discussion in successive chapters of the thesis.

2.2. Patient confidentiality or privacy?

As severally earlier on alluded to, the focal point of this research is on confidentiality rather than privacy. A bulk of this study centres on the duty of maintaining patient confidentiality and, the respect for the patient’s confidentiality is fundamental to the professional relationship between the patient and the healthcare professional. But many at times, we feel tempted to use the terms “privacy” and “confidentiality” interchangeably as if they bear one and the same meaning or connotation. The terms privacy and confidentiality are sometimes distinguished on the basis that privacy refers to physical matters, while confidentiality refers to informational material. According to the construction, it would seem to denote that, if a stranger walk into a consulting room and sees a patient being examined by a doctor, the patient’s privacy is violated, whereas if the same stranger later picks up the patient’s health record, confidentiality is violated. It might not necessarily be as simple as that. Although the two concepts were both derived from ethical principles of respect for the autonomy of persons, the desire to do good (beneficence), and the principle of trust, there is a distinction between the two, although, often seemingly unclear. In other words, a sort of distinction without difference, it could be argued that, while privacy of information is construed as a general concept, which further reflects both the individual and public interest in the ability to keep private information away from public view, confidentiality, on the other hand, it has to do with relationships and the rules that govern how information is shared within them. This section tries to clarify further that, although the two concepts bear similarities, there are significant differences in their definition and impact within the context of the professional relationship between the patient and a healthcare professional. Another significance of this section is to identify the focal point of Saudi Arabian protection to patient confidentiality, i.e., is it about privacy, or confidentiality, or a combination of both? Consequently, it is noteworthy at this point that, our focus is largely on data protection rather than physical privacy protection. It is, therefore, instructive to digress a little bit and review the concept, definitions and differences (and similarities, if any) between privacy and confidentiality to enable us buttress our choice of data protection as our focus as against privacy.

2.2.1. Privacy

Among all the human rights in the international catalogue, privacy is perhaps the most difficult to define. Not only is the difference between privacy and confidentiality blurred but defining the term ‘privacy’ involves even some more difficulties. No one knows what is meant by "privacy" because, perhaps, no single workable definition can be offered and that privacy may take different forms that are related to one another by family resemblances. For instance, what this study refers to as “chameleon-like” word privacy may denote a wide range of wildly dissimilar issues that range from confidentiality of personal information to reproductive autonomy; while others have lamented that the term tends to be ambiguous, momentary, elusive and variable. When considered generally, privacy protection is frequently seen as a way of controlling access to a person's private affairs which may include an information privacy, bodily privacy and territorial privacy. Information privacy governs the collection and handling of sensitive personal data such as credit information and medical records, while bodily privacy is concerned with the protection of people's body against invasive procedures such as drug testing and cavity searches. On the other hand, privacy of communications covers the security and control of access to all forms of communication such as mails, telephones, email etc., while territorial privacy sets limits on intrusion into the territorial space such as the workplace or public space. Under other jurisdictions, the ECHR has not specifically defined what a private life denotes for the purpose of attaching a legal right or duty to it. However, it was also held that, private life is a broad term and its scope is not exhaustive covering both the physical and psychological integrity of a person, guarantees of personal autonomy, personal privacy, identity, integrity, development, etc. In the case of public figures, their privacy is limited to those areas of their private life where it is obvious that they wanted to be alone. Often, privacy have been referred to in several nomenclatures including "that which is no one's business," “the right to be let alone,” or, a “person's interest in controlling other people's access to information about him or herself,” or "the condition of not having undocumented personal knowledge about one possessed by others." Another view considers privacy as being invaded when people approach an individual so that they can examine his or her body, behaviour or interpersonal relations. Preserving privacy in such cases would entail the creation of a physical barrier between the individual and others.' Recently, the Indian Supreme Court in Puttaswamy and Anr. vs Union of India And Ors, defined privacy as: “The ultimate expression of the sanctity of the individual. It is a constitutional value which straddles across the spectrum of fundamental rights and protects for the individual a zone of choice and self-determination.” It has also been proposed that privacy may denote as the ‘desire of people to choose freely under what circumstances and to what extent they will expose themselves, their attitude and their behaviour to others.’ The Caldicott Report in the UK, although lamented about its failure to find a “wholly satisfactory statutory definition of privacy," proposed an “acceptable” legal definition of privacy as: “The right of the individual to be protected against intrusion into his personal life or affairs, or those of his family, by direct physical means or by publication of information.” Accordingly, even when a zone of interaction is considered as being within the scope of public life, it may still fall within the scope of private life, if, for instance, the activities are intentionally or knowingly recorded systematically or permanently. A compilation of data on individuals may constitute interference a breach of privacy, except where a monitoring is done without recording. Likewise, a publication of materials beyond that which is foreseeableor not anticipated at the time of collection is serious interference with the right to privacy.

It has been argued that Warren and Brandeis’ definition of the right to privacy (of 1890 ) as "the right to be left alone" seemingly ushered in the modern concept of the privacy right. It could be safely surmised that privacy relates to secrecy (the extent of our accessibility to others), solitude (our popularity and other’s access to us) and anonymity (the extent of our being the subject of interest to others). Furthermore, the loss of privacy may not necessarily involve the disclosure of the patient’s private information because, one can lose privacy just by being the object of attention, even when no information is disclosed, and regardless of whether the attention is conscious, intentional or unintentional. Privacy "is related to our concern over our accessibility to others: the extent to which we are known to others, the extent to which others have physical access to us, and the extent to which we are the subject of others' attention." Privacy relates to the persons and/or personhood, i.e., a person’s right to use, manage and control his/her certain emotional, cognitive, or psychological "space" and the ability of a patient to control personal information or to make decisions about how his/her personal information is accessed. That is, it is the power to "deny and/or grant access” to some (personally identifiable) information about himself or to control over who can experience him or observe him. Although the term privacy is first used in tort law, the right to privacy is now one of the fundamental human rights that is clearly captured under the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR), regional conventions/charters and national constitutions that protect a person's spatial privacy (e.g., of home) and informational privacy against illegal interference by the government. For instance, the UDHR, The Arab Charter on Human rights and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) have all given protection against “arbitrary interference with privacy, family, home or correspondence”. Accordingly, the Saudi Basic Law of Governance provides: “The State shall protect human rights in accordance with the Islamic Shari‘ah.” “Correspondence by telegraph and mail, telephone conversations, and other means of communication shall be protected. They may not be seized, delayed, viewed, or listened to except in cases set forth in the Law.” Therefore, the right to privacy is the limitation, placed on the right of others to have access to information about, or the physical space, of an individual. Although the study does not intend to delve into the “space” privacy rights as applied to the fundamental rights to privacy, but in view of the cultural sensitivity of the Saudi society with regard to spatial privacy, especially during interactions between people of the opposite sex, we may examine how this unique and intricate interaction affects the patient’s confidentiality right. Furthermore, it should be noted that, the privacy limitation placed on information is regarding unlawful access rather than its unlawful sharing with (or disclosure to) third parties, which comes within the ambit of confidentiality. However, the healthcare professional in Saudi Arabia, just like elsewhere, might be at the risk of breaching a patient’s privacy right unless he/she accesses the patient’s confidential information upon the assumption of a professional relationship of the patient. It would seem, therefore, to be a breach of patient’s privacy if, for instance, a health care professional illegally accesses a patient’s electronic medical record, or illegally obtains a patient’s medical records file or someone eavesdrops and listens to a conversation between a patient and her doctor. It would, however, be different if, the access was made possible by an unjustified disclosure by someone who had legally accessed the information. In such a case, the person, who made the unjustified disclosure, would have been in breach of confidentiality right, rather than privacy right because the access was legal.

2.2.2. Confidentiality

The second arm of the human right to privacy is the control over the disclosure to the third party, of personal information already lawfully accessed. Confidentiality has been defined as “the careful husbandry of personal information,” or as the duty to maintain patient’s private information revealed during a professional relationship. More specifically, confidentiality implies the protection of personally identifiable information against access or knowledge by any unauthorised third party. The information sought to be protected must be unique to that particular patient (as opposed to information that could be attributable to any person qua person). The lawful access to patient’s private data or other similar information of this kind further creates an obligation or a commitment by the healthcare professionals to keep that data in confidence. Confidentiality then may imply two domains: that which is private (or known only to the individual) and that which is public (that which is already known to the public). The doctor may be justified in breaching the duty in the public interest and, any personal information which is already in the public domain, as in newspaper articles, is not considered private. This exception may also apply to any previously privileged information that was disclosed in breach of confidentiality. That is to say that once it is published, no matter how, it might no longer claim confidentiality. As alluded to earlier on, the right of patient’s confidentiality is predicated on the value of trust placed in a doctor-patient relationship. The patient presupposes that the doctor would, banking on this trust, refrains from revealing that private information to others without his consent. Confidentiality, too, is founded upon the ethical principle of autonomy with the goal of protecting the patient’s interests as the master/ruler of his secret. The patient should be able to decide freely what, whether, how and to whom to disclose that particular information about his/her health or treatment. One of the key features of this study is to identify the circumstances that signify breach of patient confidentiality and the remedies available to the aggrieved patient. And a breach of patient confidentiality may arise at various levels of managing the patient’s information, which may include acquiring (collection), processing and disseminating of the patient’s private information, as opposed to a privacy breach that arises because of invasion into the patient’s private affairs. The study realises that, information collection generally involves surveillance and history taking or interview. In the context of patient confidentiality, the manners in which information is conveyed may be in a form of disclosure of the patient’s complaints and other patient’s unique information on laboratory or radiological test requests. The professional may also access a patient’s intimate information through physical, radiological and pathological examinations and evaluations. How the information is acquired could potentially lead to a privacy breach, while confidentiality focuses more on whether, to whom, and how that information is further transmitted. On the other hand, information processing implies how the acquired information is stored, manipulated, and used. This process may involve aggregating the information (the grouping of various pieces of information about the patient) and identification or linking the aggregated information to the patient. At these stages, two challenges may lead to a potential breach of confidentiality; Insecurity and Secondary use: Insecurity may arise from the failure to protect stored information from improper access, while secondary use is the use of data for a different purpose without the patient’s consent. In such situations, there would appear to be a case of breach of privacy, where an individual takes advantage of the insecurity and, illegally invades into and acquires the patient’s confidential information. On the other hand, it would seem to be a breach of confidentiality, if, the professional or the health institution, having legally acquired the information, subjects it to insecurity and/or secondary use without the patient’s specific consent to a resultant disclosure to an unintended third party.

As we have pointed out earlier, the main premise of confidentiality duty is a commitment by the professional to keep a patient's information secret. Therefore, during the process of information dissemination, several actions could result in a breach of confidentiality. This may include disclosure, exposure, increased accessibility, appropriation and distortion. Disclosure is considered as revealing the patient’s truthful information to others that could result in prejudice or stereotype, while exposure involves revealing patient's bodily functions. Conversely, an increased accessibility is the act of increasing the availability of the patient’s private information to third parties while appropriation involves the using the patient’s information to serve other ulterior interest. Data distortion entails the distribution of false or misleading information about the patient. The worst form of illegal disclosure is when the patient’s information is used as a tool for blackmail i.e., the threat to disclose personal information. It is only through an unlawful disclosure of the information that a breach of confidentiality becomes effective. As in other contexts, a supposed breach of confidentiality may be justified where the disclosure is purportedly in the public interest or, if this information is already in the public domain, as in the British cases of Campbell, and that of Mosley vs News Group Newspapers Ltd. It seems that the more we try to juxtapose the terms privacy and confidentiality the more their distinctiveness becomes even more blurred. There is not a clearly distinctive and definitive differentiation between the two terms: privacy and confidentiality under the Saudi Arabian laws. Even when seen under other jurisdictions like the UK’s laws, the difference between ‘privacy’ and ‘confidentiality’ as respectively described by Article 8 of the Human Rights Act and, the Data Protection Act has resulted in more confusion. Notwithstanding the blurred distinction between the two, the takeaway is that privacy is about access to spatial or informational space, while confidentiality is about disclosure of information legally accessed pursuant to the relationship of confidence between the patient and the healthcare professional. Furthermore, confidentiality right derives its origin from the right to privacy and not the other way around. Therefore, despite the attempts made above to clearly differentiate between the two concepts, in this study, a reference to privacy or confidentiality is a orientation to an unlawful access to or disclosure of patient confidential information (data protection). Unless otherwise clearly delineated, the study does not delve into physical privacy.

2.2.3. What is Patient Confidentiality?

Patient confidentiality ‘is central to the preservation of trust between doctors and their patients.’ It represents a patient’s right to the protection of their personal information, which under normal circumstances should remain strictly confidential during the patient’s lifetime and even after their death. A duty of confidence arises when a patient discloses information to an HCP (for example, a patient to a physician) in circumstances where it is reasonable to expect that the information will be held in confidence. In the United Kingdom, for instance, confidentiality is a legal obligation that is derived from law and must be included within the National Health Service (NHS) employment contracts as a specific requirement linked to disciplinary procedures. Confidentiality is, therefore, both an ethical and a legal obligation. The right to confidentiality is an essential part of the bond that exists between an HCP and a patient. Where it is not maintained, it may lead to the patient being reluctant to reveal confidential information that is required for proper diagnosis and treatment. Confidentiality is a right that must be respected by all members of the healthcare team. Disclosing confidential information about a patient without their consent is unethical and a breach of a legal duty. The only exception is where the HCP is required by law, ethics or a contractual obligation to disclose such information. For a patient to give consent to any disclosure of confidential information, the patient needs to understand:

who the information will be disclosed to;

precisely what information will be disclosed;

why the information is to be disclosed; and

the significant foreseeable consequences.

Where a patient has given consent for the disclosure of any confidential information, the HCP must only disclose information the patient has agreed and only to the third party requested and no other use of the information can be made without further consent from the patient. As previously discussed in chapter 1, patient confidentiality is not a concept known only to the West. The concept has been considered in Islamic jurisprudence, as such contemporary Islamic scholars can produce a fatwa based on the Islamic principles in the exercise of Islamic Fiqh which is a reference to the Qur’an whenever the truth needs to be found and based on a rational questioning of what is to be human. The scholars can rationalise and determine what should be a right or duty derived from the tenets of the Qur’an. As a result of applying Fiqh, scholars have determined that, patient confidentiality should be protected. Patient confidentiality is an off-shoot of the human right to privacy and confidentiality. It needs to be noted, however, that there is a difference between both concepts. Confidentiality is the legal protection offered to a person for sharing private information with a professional with whom that person is in a fiduciary relationship. For example, in the context of healthcare – confidentiality refers to data disclosed by a patient to an HCP during dialogue in a medical appointment. On the other hand, privacy refers to the ‘legal protection of personal medical information from being shared on a public platform. Privacy legally protects the patient’s records, prescriptions and examinations from being shared or accessed by anyone other than his/her physician.’

2.2.4. Patient Confidentiality among Healthcare Practitioners

In countries where physicians are duty-bound by the Hippocratic Oath to safeguard patient confidentiality, they swear to protect patient confidentiality. For example, these words form part of the 1923 edition of the Hippocratic Oath: And whatsoever I shall see or hear in the course of my profession, as well as outside my profession in my intercourse with men, if it be what should not be published abroad, I will never divulge, holding such things to be holy secrets… By the reason of that oath, physicians have a legal as well as an ethical obligation to protect patients’ confidential information. In the UK, the Hippocratic Oath has served as the main pillar for the physician’s duty (as an ethical guideline on the confidentiality of health information) and practitioners should make it an important point of consideration in the course of treating patients. The medical information of a patient is not only what the HCP finds during a diagnosis or clinical examination or test results; it also includes information regarding the patient’s life, lifestyle and habits. Any inappropriate disclosure of a patient’s confidential information by the HCP could potentially be a threat to the patient’s reputation and human dignity. In the Islamic Republic of Iran for example, a breach of patient’s confidentiality by an HCP could be punishable upon conviction under the Islamic Penal Code. In the same vein, Iran’s Medical Council prohibits breaching confidentiality. In Saudi Arabia, the healthcare profession is regarded as a noble profession because it is related to ‘the human soul, health and life preservation which is the most precious thing.’ Under the Code for HCPs in Saudi Arabia, it is emphasised that Shari’ah has asserted the significance of keeping the patient’s secrets and confidentiality. As a guide, the HCP must never disclose a patient’s confidential information except in the following circumstances:

If the disclosure is to protect the patient’s contacts from being infected or harmed, like contagious diseases, drug addiction, or severe psychological illnesses. In this case, the disclosure should be confined to those who may become harmed;

If the disclosure is to achieve a dominant interest of the society or to ward off any evil from it. In this case, the disclosure should be made only to the official specialized authorities. Examples of this condition are the following:

Reporting death resulting from a criminal act, or to prevent a crime from happening.

Reporting of communicable or infectious diseases.

If disclosure is requested by a judiciary authority.

To defend a charge against a healthcare practitioner alleged by the patient or his/her family in relation to the practitioner’s competence or how he/she practices his/her profession. Disclosure should be only before the official authorities.

If the disclosure to the patient’s family or others is useful for the treatment, then there is no objection to such disclosure after seeking the patient’s consent.

The healthcare practitioner can disclose some of his/her patient’s secrets when needed for the education of other healthcare team members. This should be limited to the purposes of education only and to refrain from disclosing what could lead to the identification of the patient and his/her identity.

Furthermore, Article 21 of the Law of Healthcare Professions 2011 and the Council of Ministers Resolution provide for the duty on HCPs to maintain the patient’s confidentiality in the following words:

A healthcare professional shall maintain the confidentiality of information obtained in the course of his practice and may not disclose it except (as provided by the law) …

A violation of the law is a criminal liability which upon conviction attracts a fine, a warning or revocation of the license for the practice and/or a further ban from re-registration for a period of two years from the date of revocation.

In other jurisdiction like the U.K., the duty of confidentiality is enforced through four apparatuses:

Common law;

Statute;

Contract of employment; and

Regulatory bodies

Under the common law, patients who feel that their confidentiality has been breached may seek redress from a court in a civil suit. Professional registration bodies may investigate any alleged breach of confidentiality and where required, impose appropriate sanctions, which may include delisting of the HCP from the register of practitioners.

2.3. Choosing the Triple Test as Guide for Assessment of Adequacy of Compliance with Right to Privacy and Confidentiality

Despite the perennial rancour among some nations, it is no longer in dispute that human rights are universally applicable, although the modus of their application may differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. And therefore, the thesis propose isto use a criterion for the assessment of the adequacy of protection of privacy right that is not only universally applied, but also accepted in the Saudi Arabian jurisdiction. This is called as ‘triple test’ of legality, legitimate aim (necessity) and proportionality. This test, which seeks to safeguard the human rights from arbitrary abuse, is widely accepted and applied in several international human right treaties. Furthermore, Saudi Arabia has ratified the treaties, which further accept this test. Therefore, it can be argued that, the triple test is applicable to Saudi Arabia because it is part of the international legal system, and because it has chosen to ratify treaties, where the test is clearly embodied both in Islamic and UN treaties.This is because, Saudi Arabia has agreed to review, amend and/or abolish it existing laws and regulations and or the drafting of new laws to streamline them with the international human rights instruments to which the country is a party. For instance, Article 29 (2) of the UDHR provides: In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society. Similarly, the Arab Charter on Human Rights, which affirmed the UDHR in its preamble, reiterated the three elements of the test: law necessity (legitimate interests) and proportionality, at Article 4: It is prohibited to impose limitations on the rights and freedoms guaranteed by virtue of this Charter unless where prescribed by law and considered necessary to protect national and economic security, or public order, or public health, or morals, or the rights and freedoms of others. The Universal Islamic Declaration on Human Rights, at its Explanation 3, made a similar provision that emphasised on the requirements of the triple test of legality, necessity and proportionality, with a proviso that the law referred to therein, is the Shari’ah, and it relates to the Muslim Ummah (community) only: In the exercise and enjoyment of the rights referred to above every person shall be subject only to such limitations as are enjoined by the Law for the purpose of securing the due recognition of, and respect for, the rights and the freedom of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare of the Community (Ummah). The Cairo Declaration on Human Rights at Article 8 made safeguards against the infringement of human rights ‘except for the requirements of public interest’ or ‘for a necessity dictated by law’. Similarly, some international human rights conventions that Saudi Arabia has ratified, e.g., the CRPD and CRC (although not referring to privacy) have made similar restrictions. An International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners was held in Madrid on 5 November 2009 to, among others, define a set of principles and rights guaranteeing the effective and internationally uniform protection of privacy with regard to the processing of personal data. Although Saudi Arabia did not attend the conference, the Madrid Resolution allows for restrictions to the right of privacy and confidentiality subject to the fulfilment of the elements of the triple test, thus: When necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety, for the protection of public health, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others... Likewise, some other international human rights conventions, e.g., ICCPR, and ICESCR that Saudi Arabia has not ratified, and other regional human right conventions to which Saudi Arabia is not a state party, e.g., the ECHR have made same exceptions. For instance, Article 8(2) of the ECHR provides as follows: There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. Additionally, constitutional courts in several other countries and regional human rights courts have applied the principle of proportionality intending to guarantee the full respect of human rights by the state. It could easily be deduced from the above that the elements of the triple test are firmly engrained in the international human rights laws that are universally applied under laws that are applicable to Saudi Arabia. However, because of lack or inadequacy of enforcement mechanism, the triple test is not fully developed as those, for instance, under the ECHR because the ECtHR plays a key role in ensuring signatory states’ compliance with the Convention. Therefore, it may not be out of place to show why it is important to make reference to some regional interpretation of the right to privacy, e.g., the ECHR, which is not binding on Saudi Arabia. The main issue of universal declaration and international/regional conventions is the lack of, or weak interpretation, enforcement mechanisms or assurance of remedies. Of course, Saudi Arabia is not ordinarily bound by the ECHR, and therefore the ‘interpretations of human rights by the European Court of Human Rights are thus certainly not automatically guiding or acceptable'. However, the ECtHR has developed the triple test as applicable to privacy in IHRL. And, there are no available case law that interprets the principles on triple test as applicable under the Saudi Arabian jurisdiction. It is accepted that in many instances interpretations from Strasbourg are applicable universally. It is the case for the right to patient confidentiality in medical settings. Western medical model is the one that is implemented worldwide as modern medicine including Saudi. Therefore, the thesis may refer to the Strasburg’s case law interpretation of the provisions of Article 8 of the ECHR as a representative of the same principles enunciated also under those declarations to which Saudi Arabia is a state party.

The ECtHR has further developed and strengthened the triple test under the ECHR, and the thesis proposes to use any such lessons that may be used for any subsequent reform, development or enforcement of human rights law under the Saudi Arabian jurisdiction. Similarly, the interpretation provided by the ECtHR is leading and influential in the field as is reinforced by the role the EU plays in setting the standards for privacy / data protection in the world. The ECHR is grounded both on a universal and a regional inspiration which serves as the first steps for the collective enforcement of certain of the rights stated in the UDHR. Having noted above, therefore, any interferences with rights protected by the human rights laws can only be valid if they pass the triple tests, which comprises of the ‘legality test’, ‘legitimate aim test’ and ‘necessity /proportionality test’ as advanced under, Article 29 (2) of both the UDHR and other IHRLs.

2.4 The Triple Tests

Having noted above, the need for protection of human rights, this study identifies a triple test, which establishes the grounds on which human rights may be subject to certain limitations. As a corollary, the right to patient confidentiality is not absolute. As such, there are certain circumstances under which the right may be curtailed. Taking the above into reckoning, how might the law adequately provide for the protection of the right to confidentiality under circumstances that warrants a limitation? Furthermore, how might one assess whether the exceptions do not give room for abuse and arbitrariness on the part of state actors and other private individuals? The answers to these questions necessitate a discussion on the ‘triple tests.’ The tests are discussed under sections 2.4.1 to 2.4.3 below:

2.4.1 The Legality Test

The legality test requires that any restriction on human rights must be ‘provided for’ or ‘prescribed by’ law. Borrowing the Strasburg’s dicta in the cases of Huvig and Kruslin, the legality test poses four questions that beg for answers in order to establish that the restriction of the right is according to law:

Legal Infraction: Does the domestic legal system sanction the infraction?

Accessibility: Is the relevant legal provision accessible to the citizen?

Precision, clarity, and foreseeability: Is the legal provision sufficiently precise to enable the citizen reasonably to foresee the consequences which a given action may entail?

Safeguards against arbitrary infringement: Does the law provide adequate safeguards against arbitrary interference with the respective substantive rights? Does the law provide for a reasonable application/use of the data and an adequate administrative control against misuse?

Where the answer(s) to any of the four questions (above) is/are in the negative, the legality test must fail. Following from this there will be no need to proceed to the two other tests. As a result, the infringement would not be justifiable. As it relates to the right of privacy and confidentiality, where the legality test fails, there is no reason why the right should be limited.

2.4.2 Legitimate Aim Test

The second test is the legitimate aim test. Here, an interference that potentially contravenes a protected right must not only be ‘in accordance with the law,’ but must also pursue one or more of the legitimate aims referred to under Article 29 (2) of the UDHR, other IHRLs earlier on alluded to, and Article 8 (2) of the ECHR. Under international human rights law, any restriction on the rights to privacy must be necessary for pursuing at least one of the ‘legitimate aims.’ These legitimate aims may include public safety, prevention of crime, protection of morals and of the rights of others, national security and ‘the economic well-being of the country.’

2.4.3 The Proportionality Test