Family Interventions in Psychiatric Care

Chapter 1

1.0 Background

From a historical perspective, family interventions trace its roots back to the times of British psychiatrists and sociologists who studied the effects of relocating long-term mental disorder patients from hospitals to community care (Brown et al, 1996). Under the leadership of John Wing and George Brown, according to (Brown et al, 1958), one factor that could lead to successful resettlement was the creation of an interpersonal environment within the households where the patients lived. Whereas the worst patient outcomes had been experienced in hostels with little support provided to the patients, another set of poor patient outcomes were experienced in households where family members offered no warmth or support to the patients (Brown et al, 1972). Consequently, a series of studies were set up to understand the unexpected outcomes of Brown et al (1972), which used a variety of sophisticated interview methods to try and comprehend why the unexpected failure of community care was experienced (Leff & Vaugh, 1985). In the study Falloon et al (1981), the authors emphasized the value of emotional support and warmth offered by family carers to the patients.

Unsurprisingly, most of the studies recommended that seeking an alternative to family care for people with the psychiatric disorder was the best way forward. However, a small group of scientists, led by Robert Liberman, developed an opposite perspective by proposing to help the families that were so overburdened by the care of people with psychotic disorders that we're unable to express positive caring behaviors that could enhance the health and well-being of the patients (Falloon et al, 1981). According to Falloon et al (1981), Liberman and colleagues recommended a detailed education about mental disorders and their respective treatments before the delivery of knowledge on how to manage the difficulties encountered by the family carers on a daily basis. Some of the skills they intended to impart into the family carers included effective communication skills, as well as rehabilitation or nursing strategies. Fundamentally, these early beginnings of the 1970s opened the way for a series of studies on family interventions for various psychotic disorders.

1.2 Study Rationale

Psychotic disorders are a major health problem that affects families and societies worldwide. Statistics by McGrath et al (2016) on one of the most severe forms of psychotic disorder, schizophrenia, indicates that a single episode of schizophrenia has an effect on at least 7% of the adult population. Furthermore, recent reports by international health bodies indicate that at least 21 million people are living with schizophrenia globally (WHO, 2017). Whereas various regions have different baseline rates, young people, Black and minority ethnic groups have reported a higher baseline rate worldwide (Jongsma et al 2017). Nonetheless, existing scientific research indicates that psychosis does not only have effects on the well-being of the individual patient but also the family and close associates. Consequently, there is a plethora of evidence on the adverse effects of psychosis, as well as the important need for effective caregiving (Poon et al 2016). Besides, many research studies (e.g. Gupta et al 2015; Kuipers et al, 2010) have highlighted the burden of care held by caregivers, its implications on quality of care as well as its implications on patient outcomes.

A variety of literature, including Hayes et al (2015) and Gupta et al (2015) has also identified the existence of informal caregivers (e.g. spouses, siblings, or parents) of psychotic patients who report a significant rate of psychological distress and mental disorders. According to Jansen et al (2015), these incidences appear mostly during the early periods of sickness and therefore carers can be overburdened by stigma, trauma, financial constraints and fatigue. Moreover, according to Hayes et al (2015) carers are more likely to experience social isolation compared to their non-caregiving counterparts. In fact, Magliano et al (2005) observed that carers of psychotic patients may experience greater isolation than carers for patients with other health disorders. From the disease onset, carers for psychotic patients experience overwhelming situations that come along with stressful, confusing and tiresome ordeals for family and other relatives. According to Lavis et al (2015), the family carers are often exposed to various patient behaviors and symptoms that are difficult to comprehend and cope with. For instance, they may have to deal with hallucination, negative symptoms and paranoid behavior (McCann et al 2011). Additionally, according to Haydock et al (2015), family carers are also often caught up in patient behaviors (e.g. gambling and aggression) often seen as stigmatizing and anti-social within the local community. Therefore, while they may be in serious need for emotional support, the impact of the illness on daily functioning can make it difficult to even realize what information or support they need. With a large body of research evidence highlighting the negative impact of psychosis on the well-being, as well as the vital role played by family caregivers on patient outcomes, a variety of evidence-based treatment guidelines in countries such as Canada, Australia, the UK and America have included brief family interventions for psychosis as part of their care recommendations (Galletly et al 2016, Kreyenbuhl et al 2010, Norman et al 2017 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE 2014). For instance, in the UK, NICE guidelines recommend the provision of family-based interventions for people living in close contact with psychotic patients. Furthermore, recently developed specialized mental health practice approaches for those experiencing their first psychotic disorder incidences emphasize on the importance of therapy to families in close contact with psychotic patients (Marwaha et al, 2016).

Against this backdrop, there needs to be a concrete evaluation of evidence on family interventions for psychotic patient carers and how it can be implemented to enhance patient outcomes. This literature review, therefore, aims to evaluate existing evidence on family interventions for psychotic patients. The study will apply systematic methods of data identification, analysis and synthesis to highlight the most current evidence-based on family interventions.

1.3 Research objectives

To identify various types of brief family interventions for use in psychotic disorders

To explore the effectiveness and efficacy of brief family interventions for psychotic disorders

To propose a suitable brief family intervention for psychotic disorders

Chapter 2

2.0 Research Methodology

2.1 The Literature Review Methodology

Dig deeper into Empowering Healthcare Through Compassionate Leadership with our selection of articles.

The current study takes the design of a literature review, which entails critically reviewing the existing empirical literature on a particular topic. Therefore, the study relied on a literature review research methodology to identify the benefits of family intervention for patients with various psychiatric disorders. There are several theoretical underpinnings that justified the selection of literature review methodology. First, according to Bernard (2011), literature reviews facilitate easier identification of research gaps because it entails a comprehensive exploration of various pieces of literature on a particular topic. Therefore, the researcher selected the literature review method to ensure that there is proper identification of knowledge gaps regarding the benefits of family intervention for people with psychiatric disorders. The second reason for the selection of literature review methodology allows the achievement of research objectives without spending much time and resources. According to Smith (2010), literature is a form of secondary research (also known as desktop research) that as opposed to primary research can be conducted without much expenditure on activities such as travelling and data collection. Instead, the researcher relies on existing data and only needs to search, retrieve, compare and analyse the existing data to answer the research question. This literature review study focuses on evaluating existing evidence on the benefits of brief family interventions for people with psychotic disorders. In doing so, the researcher, retrieved and critically appraised existing literature material with the aim of achieving the underlying research objectives. In health care, the topic of family interventions is one of great interest to many scholars. Consequently, there are a number of studies conducted in this topic area so much so that it would be prudent and beneficial to systematically select the studies that might be most relevant to the current research interest. Therefore, to identify relevant literature material, the researcher applied various search strategies, some of which are illustrated below:

2.2 Development of the Research Question

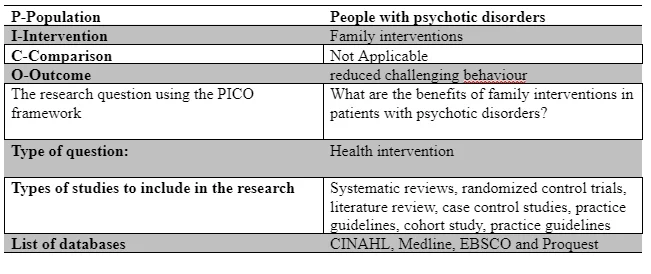

According to Bell (2014), it is impossible to achieve the objectives of any study without a clearly focused research question. In clinical research, the use of structured frameworks in developing research questions is a common practice. This explains why in the current study, the researcher used the PICO (population, intervention, comparison and outcome) framework to systematically develop the research question. With this regard, the population here involved patients with various psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, dementia and affective disorders such as bipolar disorders. Interventions referred to the various family interventions identified in the review, while the outcomes denote the positive patient outcomes including a reduction in challenging behaviour. The following table illustrates the use of the PICO framework in developing the research question:

2.3 The Search Strategy

The search strategy was systematic and followed a pre-determined process to ensure transparency and ability of other researchers to duplicate the same study if they wished to. The study relied on journal articles selected from online databases such as Proquest, EBSCO Medline and CINAHL. The medical subheadings (MeSH) of psychotic disorders such as family intervention/brief family intervention/FI/family therapy were used alongside Boolean operators such as AND and OR to combine keywords; as illustrated in the subsequent sections of this chapter.

2.4 The Databases

All the journal articles were retrieved from Proquest, EBSCO Medline and CINAHL. Bernard (2013) asserts that through online databases, researchers can easily search and retrieve literature materials compared to physical libraries that might take time. Besides, online databases were chosen as the source of journal articles because they allow the search process in those platforms is easily replicable. This enhances the study reliability (Bernard, 2013). Lastly, these particular online databases were selected because of their abundance in literature materials on the subject of family interventions.

2.5 Search Terms

Upon selecting online databases as the source of literature materials, the researcher needed various search terms for use in the search engines during the search process. Ideally, the search terms could just be typed on the search engines to automatically retrieve the relevant journal articles. Therefore, as observed by Brannen (2008), search term allow for a quicker retrieval of journal articles. In the present study, the following search terms were developed: family intervention/brief family intervention/FI/family therapy. To achieve a quicker retrieval of literature materials, the researcher used Boolean operators such as AND/OR, combining related and unrelated words to narrow and expand the scope of the search respectively. Boolean operators were also useful because they would enhance the specificity and sensitivity of the search process (Smith, 2010). For instance, AND was used to combine family therapy with family intervention to narrow the scope of the search process, while OR was used to combine brief family intervention was combined with family intervention to widen the scope of the search.

2.6 Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The author developed inclusion/exclusion criteria to establish the relevance and scope of the search process. According to Smith (2010) inclusion/exclusion criteria are limitations meant to ensure that only the most relevant studies are retrieved from the databases. They determine which type of literature materials are included or excluded in the review. However, as will be evident in the results section, the inclusive year of publication is older than typical clinical relevance because of the subject matter has la paucity of latest research. Meanwhile, the following table illustrates the inclusion/exclusion criteria together with their respective justifications:

2.7 Study Selection

The researcher saved all the results of the initial screening process which was done by reading the abstract of each retrieved journal article to exclude or include them. At this stage, all the papers that were not found to be relevant were excluded from the study. Next, the researcher read the abstracts of the remaining articles and excluded the irrelevant ones. After the second exclusion, the remaining articles were taken through another screening process for full-text considerations. All the papers that were not in full text were excluded from the study because they could not allow for a full review of their content. The researcher then conducted a manual search of the references of all the remaining studies to ensure that no other relevant study was left out.

2.8 Data Extraction

For a more comprehensive understanding of the selected journal articles, the researchers conducted a details data extraction process that included the identification and recorded of the specific information about each study. Particularly, the information of interest to the researcher was the study authors, title, year of publication, the sample characteristics, study methodology, study results, conclusions and recommendations.

2.9 Quality Assessment

The researcher relied on Cochrane quality assessment recommendations (Grade Profiler Version 3.6) to evaluate and critically assess the study quality. As part of the quality assessment process, the researcher was keen to examine the internal validity and study design by evaluating some basic elements such as detection biases, performance, and selection.

Chapter 3

3.1 Results

In literature review research methodologies, the researcher might fail to find adequate literature material or eligible studies to include in the review; or none at all. However, according to Brannen (2008), this limitation does not mean that a literature review cannot be conducted, despite posing a challenge on the general procedure of the study. While the researcher intended to include randomized control trials for purposes of quality evidence, the search process failed to yield any reliable randomized control trial for inclusion. To address this challenge, we identified the weaknesses of the reviewed studies before we could conduct a narratively scope them in the discussion section. Thus, the study acknowledged that while there might be a paucity of randomized control trials and quality journal articles for review, there must have been something published in this particular research topic. Consequently, the study included the best journal articles that could be retrieved and concluded with a recommendation for future research to address the experienced research gaps. Furthermore, due to a shortage of research on this subject area, this recommendation for change in practice becomes in handy to fill the research gap. Meanwhile, the study identified a total of 230 references after the entire search process. The studies were then undertaken through screening, whereby 210 of the studies were excluded based on abstract and tittle. The remaining studies were undertaken through an eligibility test, leading to an exclusion of 17 studies. Ultimately only three studies were included for further review. The following PRISMA chart illustrates the study selection process:

3.3 Included Studies and Methods

The included studies were Onwumere et al (2018), Burbach (2016) and Batra et al (2018). The studies were of varied research methodologies: an editorial on the research topic, (Onwumere et al, 2018), a clinical compendium (Burbach, 2016), and a quasi-experimental study (Batra et al, 2018). Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, it was impossible to identify the total number of participants cumulatively included in the review. Besides, we could not compare the control and experimental groups of all the included studies because only one study (Batra et al, 2018) included an experimental and control group. Nonetheless, each of the studies used an appropriate methodological approach in achieving their stated objectives.

3.4 Settings

Onwumere et al’s (2018) editorial was based on the UK setting, within the context of Kings College London. Burbach’s (2016) clinical compendium was based on UK’s Southampton community while Batra et al’s (2018) study were conducted within a tertiary psychiatric hospital in Nagpur India. Two of the studies (Onwumere et al 2018; Burbach, 2016) focused on both inpatient and outpatient care while one of the studies (Batra et al, 2018) focused on in inpatient. More importantly, two of the studies (Burbach 2016, Batra et al 2018) focused on brief family intervention (less than 5 sessions or at most three months program) while one study evaluated both brief and non-brief family interventions.

3.5 Participants

All the studies focused on people with schizophrenia and schizophrenic disorders together with their relatives or families. Besides, all the studies described brief family interventions and their effects on patient/family outcomes. However, the studies had a mixed reporting and discussion of results, with one of them (Onwumere et al, 2018) discussing the effect of brief family intervention among families experiencing first episodes of psychosis. In one study (Batra et al, 2018), study group and the control group consisted of 120 caregivers (60 each) caring for patients with schizophrenia. Nonetheless, the structure of education in each of the studies was different, with the most significant difference noticed in the study by Batra et al (2018). Particularly, Batra et al (2018) implemented family psycho-education as the intervention while Burbach (2016) and Onwumere et al (2018) focused on both wider and closer family network education programs.

Chapter 4

4.0 Discussion

4.1 Themes

The heterogeneity of the included studies implied that thematic analysis would be the best approach to synthesizing the results. Upon reviewing the included studies, three major themes emerged for discussion, namely the rationale for family interventions among families experiencing first episodes of schizophrenia and psychosis, the implementation approaches of family interventions and the beneficial impact of family interventions on patient and family quality of life.

4.1.1 The Rationale for Family Interventions at First Psychosis Episode

Booth Onwumere et al (2018) and Burbach (2016) highlight this theme. Onwumere et al (2018) states that while one would ordinarily oppose the need for family interventions dedicated to families experiencing first episodes of psychosis, the plethora of evidence supporting the intervention at early phases of psychosis make it worth exploring. Onwumere et al (2018) further argue that showed the impact of first episodes of psychosis on patients’ siblings and how it affects their ability to care for the patient. Particularly, the survey by Bowman et al involved 157 first episode siblings and indicated how the siblings experienced caring burdens especially in cases where the patients have a history of self-harm or aggressiveness against others. Besides, drawing from the study findings that the female siblings tended to report higher levels of carer burden, Onwumere et al (2018) argues that the negative caregiving experiences of siblings and other family caregivers necessitates and educational family intervention that would help them manage and cope with the burden of caregiving. These assertions corroborate with the observations made by Burbach (2016). Burbach (2016) begins by acknowledging the existing evidence on how the surprising nature of first psychotic experiences adversely affects caregivers. The author goes ahead to conceptualize first psychotic episodes by highlighting that they develop when the patient is in close contact with their relatives and that this makes the concerned relatives play a significant role in ensuring the patients get mental illness. Furthermore, Burbach (2016) argues in corroboration with observations by Patterson et al (2005) as well as Addington et al (2003) that the let-down experienced from unsupportive services, as well as the worry about their psychotic relatives causes a high level of distress among family caregivers and may escalate to other complications such as depression and anxiety. This justifies why various clinical guidelines such as the NICE (2014), Dixon et al (2010) and Bertolote & McGorry (2005) recommend the delivery of active support to relatives and families through education. Burbach (2016) compares this to triangle care between the patient, relatives and medical practitioners who are involved from the first contact with the care services. Comparing the findings by Burbach (2016) to the extensive evidence on the justification of family interventions experiencing the first psychosis episodes to the findings by other studies, a significant point that emerges is that family interventions are important for the fact that family caregivers help the patients navigate through the difficult journey of seeking and accessing quality healthcare. For instance, a systematic review by Pharoah et al (2010) and Mihalapoulos et al (2004) agree that brief family interventions are effective from both cost and clinical perspectives. However, it is important to note that the studies by Pharoah et al (2010) and Mihalapoulos et al (2004) were focused on long-term service users and may not be generalizable to first relatives experiencing first psychotic episodes.

4.1.2 The Implementation Approaches for Brief Family Interventions

The theme of approaches for implementing brief family interventions could not go unnoticed. This theme was particularly evident in the study by Burbach (2016) who supports it with evidence drawn for other studies. To begin with, Burbach (2016) acknowledges that brief family interventions can be implemented through various patterns of interacting with the targeted families. Secondly, Burbach (2016) observes that whereas the patterns can be implemented in many ways, the framework developed by Baucom et al can be useful in the implementation process. For instance, some interventions may focus on supporting the patient’s significant other to play the role of an assistant therapist who assists the patient in executing certain tasks such as house chores. Alternatively, other interventions may focus on family interactions problems and how the family can be supported to exchange roles so that the patient is more available for individual therapy sessions. The third approach is the focus on relationship problems such as couple issues to ensure that the patient is not under prolonged stressful situations that hinder recovery. Against this backdrop, there is sufficient literature to support Burbach’s (2016) exploration of brief family intervention implementation approaches. For instance, Trepper et al (2012) extensively explore the Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT), an implementation approach that focuses on patterns of interaction directly associated with psychotic symptoms and applies specific strategies such as scaling and miracle questions to pay close attention to possible solutions.

Burbach (2016) also review evidence indicating the challenges experienced in real-world implementation of brief family interventions, even to trained practitioners. According to Cohen et al (2009), since time immemorial, UK practitioners, as well as practitioners in fragmented healthcare systems such as the USA have experienced a challenge in implementing brief family interventions, especially because sometimes the family services are either underutilized or due to a lack of regular contact with care teams. More importantly, the study identifies various barriers to the implementation of brief family interventions including organizational systemic barriers as well as individual issues including the patient’s lack of interest in involving the family.

4.1.3 The Benefits of Family Interventions

The benefits of family interventions are more profoundly highlighted by Batra et al and Burbach et al (2016). First, the review found significant evidence for the literature that brief family interventions were associated with improved quality of life as measured by the World Health Organization quality of life scale (WHOQOL-BREF). Furthermore, the intervention group in the reviewed study showed a significant improvement in expressed emotions as indicated by the researcher’s Express Emotions scale (FFEICS) score as well as an improvement in the caring burden as measured by the Burden Assessment Score Scale (BAS). The review also revealed that seeking spiritual support and sensitizing the family on help-seeking was one of the most effective coping strategies, while ‘reframing’ emerged as the most ineffective coping strategies. Meanwhile, the review found that family intervention improved the participant’s knowledge in schizophrenia as a condition and the different strategies for managing it. Furthermore, there was an association between brief family intervention enhanced coping strategies among the study groups that received Brief intervention.

4.2 Conclusion

Regardless of the quality of journal papers reviewed, this study has identified that caregiving to patients with psychotic disorders has become a normal practice of millions of families and relatives in the world with members diagnosed with psychotic disorders. The families give invisible but valuable care to their family members despite the various challenges they encounter in the process. Against this backdrop, this study has found that family intervention is beneficial to families of people with psychotic disorders, especially those experiencing first episodes of psychosis. The reviewed studies including a quasi-experimental study have shown an association between brief family interventions and improved quality of life, better perception of care burden and general knowledge in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. However, the significant limitations of this study affect the generalizability of its findings. Apart from the quasi-experimental study, the other reviewed studies were based on fundamentally weak methodologies. Both the commentary and the clinical compendium and the editorial review of evidence did not give any details about the respective research methodologies; a phenomenon that largely affects the reliability and application of their evidence. This study, therefore recommends further research on this topic area; with more robust methodologies such as randomized control, trials to improve the quality of existing evidence. Further research should also concentrate on larger populations to improve the validity, reliability and generalizability of the evidence. Nonetheless, the review highlights the dire need for a change in practice for brief family intervention in acute phase, or families experiencing first episodes of schizophrenia. While the proposed change in practice will encounter challenges related to a shortage in research evidence, there is hope that the research gap will be filled to some extent. If the studies by Batra et al and Burbach could find significant evidence that brief family interventions were associated with improved quality of life as measured by WHOQOL-BREF, a practice improvement will undoubtedly contribute to positive patient outcome.

References

Brannen, J. (2008). The practice of a mixed methods research strategy: Personal, professional and project considerations. Advances in mixed methods research: Theories and applications, 53-65.

Bernard, H. R. (2013). Social Research Methods: Qualitative And Quantitative Approaches. Los Angeles, Sage Publications.

Batra et al (2018) Effect of family psycho education on Knowledge, Quality of Life, Expressed Emotions, Burden of Disease and coping among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia, Journal of Dental and Medical Science;s 2279-0861.Volume 17, Issue 8 Ver. 5, PP 59-7

Brown, W., Birley, T., Wing K. (1958) Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic disorders. A replication. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;121:241–258.

Burbach, F.R. (2016) Brief family interventions in psychosis- a collaborative, resource-oriented approach to working with families and wider support networks. Chapter 8 in Pradhan, B., Pinninti, N. & Rathod, S. (Eds) Brief interventions for psychosis: a clinical compendium. Springer Brown GW. Birley JLT. Wing JK. Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic disorders. A replication. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;121:241–258.

Galletly, C., Castle, D., Dark, F., Humberstone, V., Jablensky, A., Killackey, E., et al. (2016). Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 50, 410–472. doi: 10.1177/0004867416641195

Haydock M., Cowlishaw, S., Harvey, C., and Castle, D. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of problem gambling in people with psychotic disorders. Compr. Psychiatry 58, 122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.01.003

Hayes, L., Hawthorne, G., Farhall, J., O’Hanlon, B., and Harvey, C. (2015). Quality of life and social isolation among caregivers of adults with schizophrenia: policy and outcomes. Community Ment. Health J. 51, 591–597. doi: 10.1007/s10597-015-9848-6

Gupta, S., Isherwood, G., Jones, K., and Van Impe, K. (2015). Assessing health status in informal schizophrenia caregivers compared with health status in non-caregivers and caregivers of other conditions. BMC Psychiatry 15:162. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0547

Jongsma, H. E., Gayer-Anderson, C., Lasalvia, A., Quattrone, D., Mulè, A., Szöke, A., et al. (2017). Treated incidence of psychotic disorders in the multinational EU-GEI study. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 36–46. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3554

Jansen, J. E., Gleeson, J., and Cotton, S. (2015). Towards a better understanding of caregiver distress in early psychosis: a systematic review of the psychological factors involved. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 35, 56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.12.002

McCann, T. V., Lubman, D. I., and Clark, E. (2011) First-time primary caregivers’

Norman, R., Lecomte, T., Addington, D., and Anderson, E. (2017). CPA treatment guidelines on psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia in adults. Canad. J. Psychiatry 62:706743717719894. doi: 10.1177/07067437177198 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014). Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults: Treatment and Management. Clinical Guideline 178. London: NICE

Onwumere J, Jansen JE and Kuipers E (2018) Editorial: Family Interventions in Psychosis Change Outcomes in Early Intervention Settings – How Much Does the Evidence Support This?. Front. Psychol. 9:406. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018

Poon, A.W. C., Harvey, C., Mackinnon, A., and Joubert, L. (2016). A longitudinal population-based study of carers of people with psychosis. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 26, 265–275. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015001195

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts