Measuring Fashionability Fashion Items

1.0 Introduction

The fashion industry has been characterised by trends, which are fast changing, short life-cycle of products, as well as high uncertainty. In this regard, fashion designers are obligated to come up with new fashion designs, within a short time, in order to fulfil consumers’ needs, and this is noted to be quite challenging (Brannon, 2010). Notably, fashion entails an entirely different life-cycle and inflation, as compared to other products/services, because fashion trends appear cyclical as old designs often have a great inspiration for current designers. It is also significant to consider the fact that fashion also has significant power over consumer behaviour (Entwistle, 2015). In this regard, it is upon fashion designers to become aware of what consequences their choices entail. Presently, many consumers use the internet in facilitating their online shopping, and this makes it convenient for consumers who prefer not to go to physical shops to purchase fashionable items. Considering the growing competition fashion, fashion designers take the responsibility of monitoring the factors that affect potential customers amid their buying journey, for them not to lose their customers to their competitors (Ferraro et al., 2016). In facilitating this, most fashion designers avoid fashionability index, as it hinders more sales of fashionable items.

This thesis purposes to expound on the measurability of fashionable items/ fashionability. In this regard, it will engage the qualitative approach, where a face-to-face interview will be conducted on 40 female college students (fashion consumers), and 12 fashion designers. The interviews provided to them will be based on the following primary and secondary research questions:

1.1 Research questions

Primary research question:

What are the factors to consider while measuring the inflation of fashionability/fashion items of women’s clothing?

Secondary research questions:

-

Why is there no fashionability index in the women fashion industry?

How are women clothing items measured and what are the perceptions of consumers and designers on measuring clothing items?

How does online shopping affect a consumer’s choice of shopping?

How do consumers and designers perceive the current fashion trends and how does the fashion cycle affect their perceptions of the concept of fashionability?

1.2 Aims

-

To find out the factors that should be considered while measuring the inflation of fashionability/fashion items of women’s clothing.

To find out the perceptions of fashion consumers and fashion designers on the measurement of fashionability/fashion items, especially women’s clothing

The main aim of this study is to explore and evaluate the factors that affect measuring the inflation of fashionability or fashion items for female customers. This study will identify and discuss the factors that can be considered by fashion designers while designing and developing fashionable items for their female customers. The research engages in exploring aspects such as reasons for lack of fashionability index for female fashion items in the industry. It also explores perceptions of both the female customers and the fashion designers, along with investigating the impact of online shopping on customer behaviour. In order to conduct this study, the researcher contacted 40 female college students and 12 fashion designers and conducted a face to face interview with them. The data has been analysed through a qualitative approach.

1.3 Objectives

-

To investigate the reason why there is no fashionability index in the women fashion industry

To investigate how women clothing items are measured

To interview selected fashion designers and fashion consumers on their perceptions on the measurability of fashion items

To investigate how online shopping affects a consumer’s choice of shopping

To investigate how fashion designers and fashion consumers perceive the current fashion trends and to identify how the fashion cycle affects their perceptions of the concept of fashionability.

1.4 Structure of the paper

The structure of the paper is as follows: The paper is categorised into five chapters. The first chapter is the introductory chapter, and it provides the problem to be explored in the paper, the context of the paper, research questions, aims, as well as objectives of the paper. The second chapter is the literature review chapter, which first provides the fashionability approaches; economic, sociological, psychological, and political approaches. After that, this chapter will provide the literature review on fashion trends and fashion cycle, leading on to the provision of the measurement of clothing items. Following this, the study of online shopping for fashionable items will provide information on how people shop online and how their choices of shopping are affected. The third chapter is the methodology chapter, and it will provide the underpinnings on qualitative research, the sampling strategy to be used, how interviews will be conducted and the structure of the interview. Moreover, this chapter will provide the data collection procedures, data collection, data analysis, limitations, and finally the ethical issues involved in the research. The fourth chapter will be the findings and discussion chapter, which will be in line with the research objectives. Finally, the conclusion and recommendation chapter will summarise the content of the thesis. The limitations of the current research will be presented, as well as recommendations for further research.

2.0 Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

The literature review will answer the question – How to measure inflation for fashionable items for women?. The knowledge obtained through the literature review will help in exploring and understanding different aspects of fashionability index. In addition, it will also help in developing fashionability of clothing. The literature review is based on the primary, and secondary research questions of the research, which is as provided below:

Primary research question:

What are the factors to consider while measuring the inflation of fashionability/fashion items of women’s clothing?

Secondary research questions:

-

Why is there no fashionability index in the women fashion industry?

How are women clothing items measured and what are the perceptions of consumers and designers on measuring clothing items?

How does online shopping affect a consumer’s choice of shopping?

How do consumers and designers perceive the current fashion trends and how does the fashion cycle affect their perceptions of the concept of fashionability?

How prices affect the customer behaviour and utility of the fashionable clothing items?

This chapter uses academic theories, scholarly articles, as well as concepts that ground the research. Starting with the fashionability approaches; the chapter will include the economic, sociological, psychological, and political approaches. The literature will extend on to discuss fashion trends and fashion cycle, leading on to the provision of the measurement of clothing items. Following this, the study of online shopping for fashionable items will provide information on how people shop online and how their choices of shopping are affected. To answer the above question, each section will discuss the fashionability index, thus providing the reasons and explanations for why the fashion industry does not have the fashionability index.

2.2 Fashion approaches

Lipovetsky (2017) indicates that fashion is regarded as a complex structure that has different tendencies. For instance, it cannot be defined or rather, it cannot be described from a one-discipline viewpoint despite it being clear that fashion has high importance which is presented in various life aspects such as in politics, entertainment, law, academics, and even business. Until recently, its academic circles failed to acquire deserved attention. Majority of scholars such as Niinimäki (2013) and Cillo et al. (2010) acknowledge the nature of fashion in respect to its sociological and psychological aspects. However, its artistic nature has not been widely accepted and notably, from its economic and cultural-economical aspects, fashion is presently examined just by a small percentage of its relation to academics. On the other hand, fashion trend poses as a central mechanism; as a product, it is regarded as creative and culturally positive. Referring to fashion as a mechanism creates competition amongst styles and also aids in creating and maintaining social orders (Fletcher, 2013). As a product, fashion is priced and as well as being expressed as an identity; it also has a social distinction; for this reason, it does not have an index. However, beyond social economic and cultural values, the attributes can be given to fashion products. According to Hines & Bruce (2007), dresses are noted to be the materialisation of aesthetic, spiritual, symbolic and authenticity values, although many designs are serving various practical purposes and daily usages. In high-fashion apparels, they are produced for art-for-art sake. The following sections will provide fashion, based on economic, sociological, psychological and political perspectives while reviewing various significant fashion-related academic theories.

2.2.1 Economic approach

In the modern world, the fashion sector poses as a cognitive-cultural economy and it is amongst the worlds most significant and creative industries. Notably, the fashion industry plays a vital role in economic development, as well as urban policy. On the other hand, it is also evident that fashion represents a conventional manufacturing industry that produced the material foods, distributions, logistics and commercial channels (Skov & Melchior, 2008). As a design industry, fashion plays a crucial role in the cities’ image, with its purpose to produce innovative ideas and brand values. Thus, posing as the reason it does not have a fashionability index. Since the beginning of history, fashion is developed from a small economic sector that has industrial orientation, and a design orientation, where design is noted to be equal, if not regarded as higher when considering the process of manufacturing. Additionally, Brannon (2010) also points out that based on its sectoral change, changes may arise from trade volumes. Fashion has purposely grown global, based on taste globalisation, and global labour division, thereby, preventing the concept of fashionability index.

The significance of fashionability also lies on the fact that clothes purpose to satisfy the basic, and social needs, as presented in the work of Maslow (see fig 1). At a given extent, every individual gets involved in fashion, because everyone should wear clothes. By understanding the Maslow’s Need Hierarchy theory, a better comprehension of the progression of customer behaviour can be obtained. This way the researcher can explore the behaviour of customers in the context of their perception towards measuring the clothing items, as well as during online shopping. On the basis of the need hierarchy theory, the researcher can also explore the aspects of the fashion cycle thoroughly.

Psychological need

It is by nature that human beings should be warm and as such, clothes serve the purpose of basic shelter. Outdoor clothes are noted to be outrageously expensive, yet they protect consumers from various extreme elements such as harsh weather conditions, and also allows them to get more respect, thus, controlling their self-esteem. In this regard, fashionable items, just like clothes, serve the psychological needs to consumers (McLeod, 2007).

Safety

It is significant to note that humans should feel safe. Clothes protect them from elements, which are regarded as more dangerous. Fashion designers create more significant body armours continually. However, expensive, it is worth noting that wearing a more expensive borderline type of body armour in a safe country poses as a way of meeting an individual’s self-esteem needs (Lion et al., 2016).

Love/Belonging

Humans need to be loved and also to belong to a specific social group. In this regard, clothes pose as an expression of love. For instance, uniforms express a sense of belonging, and similarly, fashion tribes also express a sense of belonging to a specific category of individuals.

Esteem

Often, humans need respect, as well as status. In this regard, clothes can be regarded as a form of consumption, which confers respect, as well as status to wearers. In line with this, fashionable items also serve esteem needs, and it is evident that the more expensive a fashionability is, the better.

Self-Actualisation

Owing to their aesthetic values and certain novelty values, clothes provide social appreciation. Fashion is a significant tool used for satisfying an individual’s self-esteem and also the needs for self-actualisation. They even express the wearer’s personality, thereby, fulfilling loftier needs such as creativity, authenticity, and spontaneity (Lion et al., 2016).

Overall, the most constant, yet significant need for fashion is encouraging fashion organisations to establish novel-seeming goods through innovation and experimentation, while avoiding the fashionability index, thereby aiding in providing a high rate of turnover. Accordingly, the fashion industry generates much profit to the UK, as compared to music, books, or even movies altogether.

Figure 1: Figure illustrating Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

SOURCE:

(McLeod, 2007)

The women fashion industry entails a fast-changing trend with products having short life-cycles and high-demand uncertainty. These characteristics encourage organisations to develop various strategies such as product diversification, agile supply chain and raise of investment about communication, marketing and strengthening significant information with various intermediaries (Lion et al., 2016). In a highly competitive environment, fashionability inflation is high, and the consumption of culturally-oriented fashion industry and the value creation often depends on the introduction of innovation, network building, maintenance and semiotic production. The success of fashion organisations needs food media connection, design institutes and dynamic network intermediary. According to Macchion et al. (2018), the intermediaries in fashion fairs are significant actors within the fashion industry as they aim to put the work of designers within their business context, shaping and regulating the fashion industry, as they are connected both globally and locally.

2.2.2 Sociological approach

Fashion poses a social phenomenon which acts as a tool for various individuals, classes, and social groups to express their affiliation and social identity. At the same time, it serves a purpose to segregate or differentiate themselves from other individuals, thereby posing a challenge to fashion organisation to avoid the incorporating fashionability index in their designs. According to Macchion et al. (2018), for instance, folk dresses represent nationality, culture, regional identity, financial status, or even age, and as such, they provide significant information regarding personality and temporary mood to their wearers. Owing to the opinion that fashion poses an excellent mirror for looking into an individual’s social status, it can also be used for a group of people. Due to the desires of people to belong to specific higher social classes, a majority of people are struggling to reduce various external features of the differences of classes and imitation of higher class style, referred to as the elite. Therefore in various classless societies, either fashion is very stable, or it does not exist (Khan, 2017). Fashion studies provide good societal cross-section as the historical background of garments reflects social ideas, the social, cultural, as well as economic life, and also development.

2.2.3 Psychological approach

Fashion choices contain two paradoxical explanations, based on a psychological perspective. Similarly, according to Entwistle (2015), it assists people in seeking individual differentiation and also social equalisation. Several scholars discovered that certain tribes that live under same conditions often develop different forms of fashion within their same age groups, and this presents uniformity, as well as individual differentiation. However, in the present globalised world, which entails depersonalisation, people have the desire for individual uniqueness while observing a variety of fashion choices. For this reason, there lacks the fashionability index, for the needs of such consumers to be met. Consumers prefer purchasing clothes that significantly present who they are, the uniqueness of their personalities, qualities and values (Niinimäki et al., 2015). The apparels that they choose is often symbolical to their identity, and also a tool that they use in gaining their desired attention. For instance, amongst young people, they have the desire of becoming autonomous, and interdependent, leading to personal fashion development. Personal fashion development can be characterised in fashion, and its effect can be on a high scale. In an instance where personal fashion development occurs, the self-imitation replaces the desire that comes with imitating the masses. An individual’s style is often a constant change, due to the continuous comparison that exists between others and themselves (Jeffers McDonald et al., 2015).

2.2.4 Political approach

Fashion can be regarded as a political tool defined by its use since the start of its history. Various governments are using it in realising their significant purposes, whether it is to do with nation building or whether it is economic driven (He & McAuley, 2016). For example, the fashion industry in China depicts that fashion dynamics can be different, based on different political ideologies. Political ideologies have a significant influence on various social norms, which then determines economic structures. Social norms also purposely form the perceptions of individuals regarding fashion and aesthetics. Based on Maoism, and the Soviet-era fashion, it was noted that fashion was uniform and as such, it entailed creativity, which was suppressed (Jeffers McDonald et al., 2015). Economic growth, as well as democratic societies, support the idea of creativity, and they provide sufficient freedom in fashion while avoiding the fashionability index. While considering democratic societies, fashion poses as a suitable means of expressing the unity of a nation and the identity of a government that supports the innovative usage of craftsmanship. It is then clear that fashion provides a valuable tool, which is essential for strengthening a creative economy, fostering relationships with various neighbouring countries, and also attracting the entire international market. In the writings of Niinimäki et al. (2015), fashion is said to be highly dynamic, and its inflation rate is high. For this reason, designers are obligated to come up with the concept of novelty in each season, whilst involving innovation in their variety of collections, and when they need to get inspiration from the old dresses that they used to design. According to Macchion et al. (2018), a modern piece of the dress does not only present individual culture, but it preserves essential knowledge that is accumulated in all centuries. There is a big challenge that poses for designers, as they try to find a balance between satisfying the individual needs, social culture and also to remain to be economical. Although fashion represents individual needs, it is also a product that considers social demands, which often evolve from the creation of interaction between individuals, their socio-cultural context and intermediaries.

2.3 Fashion trends

Fashion trends are influenced and are also created from the supply and demand side of the fashion industry. This is done by fashion cities, various multi-brand corporate organisations and designers that range from less experienced ones to star designers. It is clear that fashion is regarded as complex, and also multifactorial. In this regard, it is likely to have an evolution from suppliers’ interaction, offers, and the demand of the buyers (Okonkwo, 2016). Rather than having much thought regarding fashion as some actors dictate it, it is essential to have a deep impression of it being an end-product of a significant process that evolves under various circumstances and influences.

It is evident that sales and present trends are highly monitored, and it is clear that there is serious demand for many trend predictions, owing to the method by which fashion is decided, be it skinny jeans or straight, there will be no expediency. As explained by Godart & Galunic (2019), anything can be regarded as fashionable. Consumers often have two types of demand for goods and services that can be categorised by the motivation that is behind their assumptions. Demand can either be functional and can also be non-functional. In this regard, non-functional demand can be distinguished into external utility effects, irrational, and also speculative demand. Based on external utility effect, there are three different effects, which influence consumer demand, and these include bandwagon effect, Veblen effect, as well as snob effect (Sanchis-Ojeda et al., 2016).

2.3.1 Bandwagon effect

A product can be trendy and also highly in demand because it becomes accessible to many. Many people have the urge to be part of a group, to join a specific crowd, and to have the society appreciate them. In this regard, they would have a purpose to wear, consume, do, and behave just like others. As such, a consumer becomes fashionable in an instance where he or she wears similar apparels like the rest (Vittayakorn et al., 2015).

2.3.2 Snob effect

A product cannot be considered fashionable when more people decide to consume it; for this reason, fashion organisations avoid similarities and embrace uniqueness by avoiding the fashionability index. After knowing that a product is accessible to many people, its value decreases before the eyes of the consumers. People have a changed mind, they desire to be different from the rest, be unique, and try to overcome their desire of being part of the more significant group (Gu et al., 2017).

2.3.3. Veblen effect

According to Gu et al. (2016), Veblen studied fashion, as well as “conspicuous consumption.” He also studied their relationship with the behaviour of humans and their social status. In this case, product demand increases sharply when its prices also increase. Consumers desire to express their status, and their prestige using a product. Herbert Blumer, who was a sociologist, became the first person to bring forth the idea of fashion, in line with collective selection (Singh et al., 2015). By his theory, he claimed fashion evolves, based on a collective process, in instances where many people, as a result of their personal choices, tend to choose from already existing styles, and they form a collective taste that is manifested in the trends of fashion. The trend themes often reflect on the spirit of a specific time, within which people are living. Although this trend evolves through the choices of individuals, due to their collective character, it significantly represents society. New trends often bring together a specific new thing, which may be slightly innovative in fashion (Stone & Farnan, 2018). The trend features are recognisable, are design elements, and are also shared. People quickly recognise and also adapt to various new fashion waves, owing to their metonymic thoughts. However, it is also clear that only one, smooth and well-structured feature becomes enough for people to have an understanding of the complexity of the fashion trend concept. A high demand arises amongst individuals preferring such items that are part of a fashion trend. Scholars such as Grant (2015), say the desire of being fashionable often manifests in people’s constant ambition of accessing the fashion that is embraced by individuals of higher social status. For instance, people in tribes often depict preferences, and also an attributed higher value towards foreign fashions, which in most instances, are unknown to them. This kind of ambition and motivation to the elite that is differing from the masses often keep fashion trends in various continuous changes.

Kennedy et al. (2017) pointed out that the conditions of the development of a trend, based on an economic perspective are as follows: enough individuals should purchase a product, having a similar prevalent and trending feature. Secondly, individual personal preferences of consumers should purposely be satisfied by a given product, whereby, the trend should significantly provide something that is sufficiently new (Gu et al., 2016). When talking about the cultural heritage trend elements, with a purpose to come back to fashion, it is clear that there is more that is added to the trend, other than the continuous cyclic rotation of trend. Folk art includes national feelings and a representation of the identity of a nation. As such, there is more that needs to be explained regarding the revival of the fashion in cultural heritage, other than just the unconventional trend changes (Singh et al., 2015).

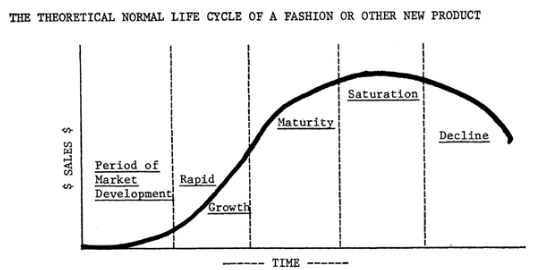

2.4. Fashion cycle

Putting into considerations, the early stages of the fashion industry, there were majorly two fashion seasons, and these included winter and summer. Presently, there has been an increase in production; various bid fashion brands often aim to launch monthly new collections, as well as capsule collections to the market (Spragg, 2017), in a bid to avoiding fashionability index as it declines the fashionability of items. Currently, there is a rapid change in trends, whereby, products have a short life-cycle, making consumers only accept fashion temporarily. Whereas, according to Noh et al. (2017), fashion also has an entirely different life cycle, as compared to either products or services. This is because fashion is cyclic, and it is well represented in bell-shaped curves, as shown in the figure below:

Figure 2: Fashion product life-cycle

SOURCE:

(Spragg, 2017)

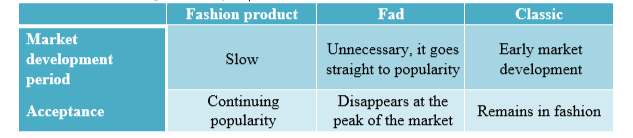

According to Tutia et al. (2017), he distinguished the life cycles of three product; fashionable products, classics and fads. They are distinguished, based on the period of their market development and the duration that they are accepted into the market as shown in the following table:

Table1: The distinction of the life cycles of a product

SOURCE:

(Spragg, 2017)

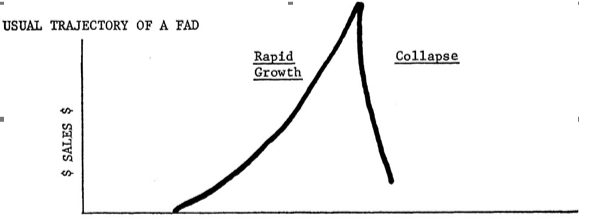

Notably, Tutia et al. (2017) indicate that the period of market development of a product that is considered new in fashion is often slow, and its popularity forms a plateau, before its declining phase. In the case of fads, the period of market development is not always functional, because the product becomes popular in a short space of time. However, this is only for a short period, as provided in figure 3. Based on the term classic, products that never run out of fashion often do not need a long introduction into the market as provided in figure 4.

Figure 3: The Life cycle of a fad

SOURCE:

(Spragg, 2017)

Figure 4: The life cycle of classics

SOURCE:

(Spragg, 2017)

It is significant to note that when a trend is beginning, only a few people become excited about the method, idea, practice, or even the style, which receives a higher evaluation in the society, and this forms the basis of the avoidance of fashionability index. Evidently, within a short time, more people become willing to follow such a similar style until it gets outdated, or when a new fashion emerges (Liu et al., 2018). Various attributed values and fashionable apparel qualities become automatically shifted to the novelty, and another trend in fashion takes shape. These cycles get shorter by the time but, their peaks get higher as indicated in figure 2, when the design approaches its advanced stage and gains enough popularity, its price and value declines. When many customers purchase it, it becomes profitable for monopolistic designers to be able to create an entirely new design. The price of the newly created design is made higher again (Vincent, 2017). This cycle becomes a repetition, which happens periodically. To provide a better understanding of the workability of the fashion cycle mechanism, a more in-depth explanation is provided for the diversification process of the fashion house. For example, Zhang et al. (2018) gave an example where Armani owns three different fashion product lines, including the Emporio Armani, Armani, and the Armani Nuove. These product lines differ, based on their designs and prices, but not in the product types. The new design that is similar to that of the introduction phase of the trend is presented at a very high level and a high price. Within time the same design would be offered for a much lower price, and at a lower line.

Various changes in fashion trends contain an entirely different rhythm. According to Vincent (2017), fashion design innovations often appear in dynamic regularity. The long and short run fashion can easily be distinguished, based on their cycles. A short run cycle takes just a few months or even a few years before another style appears. Designers have the challenge of satisfying the customer’s desires for novelty, and the change within a short period. New and long-run trends emerge in a historical style continuity, implying that they can take decades or even centuries. Zhang et al. (2018) state that the change evolves from a single extremity to another, and within thirty-fifty years or so, all the significant syles appear once. Notably, this progress is slow, as the new trend in fashion is often presenting small changes, which are mainly emerging in aesthetics from a previous fashion trend. They aim to adjust the current culture pieces, society and take significant consideration on the importance of the desires of the customers for expressing their individuality with trending fashion (Liu et al., 2018). Often, these changes appear yearly, and from season to season. Importantly, they are majorly manifested in the pattern, fabric, and colour. The introduction frequency to new products gradually declines, especially in a competitive environment, where the design is only sold to individuals from high social classes, which is referred to as the elitist case when considering the fashion cycles. A monopoly suggests that egalitarian cycles do spread over the entire population, especially where fashion prevails and before an innovation is brought forth (Vincent, 2017).

Based on the economic point of view, Spragg (2017) indicates that more differences exist between both the short run and the long run cycles. Long run cycles contain highly fixed costs, and this is contrary to short-run cycles, which have low-fixed costs. Additionally, long run cycles have their designs that stay in fashion, within an extended period. Therefore, they entail high prices, in a bid to covering the costs. When the fixed cost is relatively small even within a short period, people tend to purchase from other products that cover the expenses and bring profit. Whenever new designs appear quickly, within a short period after another, the fashion tends to spread rapidly amongst masses (Vincent, 2017). As a result, the profit that the designer gets is often not much. In a competitive environment where there is a short frequency regarding cyclic changes, the designers acquire the best situation. During the short life cycle, designers acquire many advantages with their products, majorly because of the dynamic changes of varied collections.

On the one hand, they keep enticing their consumers to purchase more, whereas, the consumers have different taste changes within a short time. According to Zhang et al. (2018), in an instance where there are a dynamic stock changes, even without the innovation of revolutionary designs, the designers satisfy the demands of their customers, from the consumer’s viewpoint, they regard short trends are better as compared to long trends. In a bid to adapting to various fashion quick changes, designers should be obligated to be up-to-date. They should involve extensive market research and acquire broad knowledge regarding the past and the current fashion state. In such a case, inspirational sources that are provided to the designers are noted to have better quality, creativity and entailing original design works (Liu et al., 2018).

2.5 Measuring clothing items

According to Fischer et al. (2017), measuring clothing items have been of significant interest to the research on clothing, because it is regarded as a crucial element for determining the quality of clothing, and overall satisfaction of a customer. Due to the various characteristics which apparel might have, multiple scholars, define clothing fit using various dimensions. In line with this, they define clothing measurement as the relationship of clothing to the body, combining various visual elements to fit onto the body and assist in evaluating the comfort of the body (Desmarais & Desmarais, 2016). A good measurement is widely defined, and this depends on various fashion trends, standardised fashion industry sizes, and individual perceptions with regards to good fit. Clothing measurement is a complex property, which is primarily affected by factors such as style, fashion, amongst others. Although a well-fitted cloth could be challenging to define, based on individual preferences, various scholars such as Liu et al. (2018), base their focus on fit and view it from the designer-mediated perspectives. On the other hand, other scholars have based their focus on their perspectives of the consumers (Fenimore, 2018).

2.5.1 Measuring items from the designer-mediated perspective

Concentrating on the designer-mediated perspective, Blackie et al. (2016) indicate that fit is measured using a standardised set of criteria, referred to as the standard of fit. When fit undergoes an evaluation using the traditional manner using various fit models, technical designers asses these fit clothes on a live model or through using a 3-dimensional scan, to fit the analysis. During testing, the designers ask the model to either sit, walk or engage various body motions while wearing the garment (Shin & Damhorst, 2018). The make use of a standard of fit, which refers to a set of various physical characteristics used in a fitted garment, in evaluating whether the clothe is appropriately measured on looks good on a body, online, balance, as well as the fabric grain (Joseph, 2017). There are significant elements, which are crucial in determining a clothing fit, and they include ease, grain, set, balance, as well as the line. Ease is the space amount existing between the body and the cloth; the line is associated with the cloth seams; grain refers to the existing relationship between the pattern, the wearer, and the fabric. Balance is for symmetrical clothes, where it means having the same distance from both the right and left side of the wearer’s body. The set depicts the smoothness of the clothing on the body, having an absence of either pulling or wrinkling of the cloth (Shin & Damhorst, 2018).

2.5.2 Measuring items from the consumer’s perspective

According to Zeugner-Roth et al. (2015), for consumers, they consider the size or fit, as well as the comfort of the clothing when deciding to purchase what to wear. In this regard, consumers perceive the fitness of a cloth, based on two perspectives. One is its visual representation when the wearer looks in a mirror, or when looking down at oneself and the second is tactile, which is how the wearer feels the cloth when wearing it. Consumer’s perceptions of well-measured cloths can be examined, based on two viewpoints, and those are nominal and operational (Dessart et al., 2016). In this regard, the nominal fit refers to the extent to which the cloth differs from the body; the operational fit is evaluated by use of standards, and the concepts of fit. The fit preferences of consumers are affected by various factors such as body image, personal comfort preferences, modern fashion trends, body shape, lifestyle, and age, amongst other factors. Overall, Escobar-Rodríguez et al. (2017) point out that it is significant to take note of the fact that the satisfaction of consumers has had considerable attention in various cloth-related areas, including product development and apparel design. This is because fit satisfaction directly affects the buying behaviours of the consumers when they are shopping for clothing. However, it is a challenge for various apparel retailer and merchandisers to meet all the needs of the consumers, based on various factors that affect their satisfaction. Personal, and external factors influence the satisfaction of consumers when it comes to fit. The personal influences relate to the body cathexis and physical body dimensions. External influences are the fashion figures along with the socially ideal body (Shin & Damhorst, 2018).

2.6 Online Shopping of fashionable items

Kawaf & Tagg (2017), state that in the present world, the usage of the internet in facilitating online shopping for consumers has made it convenient for consumers that intend to purchase fashion items. Over 2 billion people spend their time on internet shopping, making online shopping is advantageous in a variety of ways. The latter sentiment makes it of importance to identify consumer’s behaviour while relating it to online shopping. Based on the growing competition fashion organisations should be obligated to monitor the factors that affect potential customers amid their buying journey, for them not to lose their customers to their competitors (Ferraro et al., 2016). The factors that affect the consumer’s choice for shopping include the following. Firstly, the internet provides customers with sufficient access to information on various products and services, which then makes them understand the fashionable items that are of quality, which in turn makes them choose the best choice for shopping. Secondly, according to Echevarria et al. (2016), consumers have ample time for shopping, and this enables them to have more control, using less effort and greater efficiency in selecting the fashionable products, which they desire. This changes their choice of fashionable products while encouraging them to explore more options. Thirdly, is the fact that online shopping allows consumers to have a deep understanding, which then creates, attitudes and beliefs that are separated from the psychological characteristics and determined by experiences that are associated with learning and even previous experience (Han et al., 2015). In this regard, they become sensitive to the pricing strategy of most fashion firms, and focus their purchase decisions on products that have the lowest prices, or rather; they develop the best value for their money when they decide to engage in online shopping. There are factors that affect consumer behaviour, and these have been identified. They include the marketing effort, emotional factor, privacy factors, and socio-cultural factors (Peng et al., 2016). Research by Shephard et al. (2016) indicates that online shoppers are affected by psychological factors, which include perception, personality, and attitudes, and these affect their choices for shopping.

2.7 Conclusion

The reviews from the literature provided are substantial, as they provide sufficient data on the approaches of fashionability. The fashion trends and fashion cycle are significantly provided. Insightful reviews on measuring clothing items have as well been provided, and finally, the scholarly studies on online shopping of fashionable items are also included. Overall, it is evident that these academic reviews will assist in delivering backed-up information as evidence to be used in the next chapters of this paper such as the appropriate methodology to be applied, and the discussion to be used.

3.0 Methodology

3.1 Introduction

This exploratory research used a qualitative approach, by utilising semi-structured, one-on-one interviews, in order to provide significant insight, as well as in-depth understanding on the issue of fashionability, and how it influences the perceptions of both consumers and designers. This chapter will provide the underpinnings on qualitative research, the sampling strategy to be used, how interviews will be conducted and the structure of the interview. Moreover, this chapter will provide the data collection procedures, data collection, data analysis, limitations encountered, and finally the ethical issues involved in the research.

3.2 Qualitative research

The qualitative research used in this research relies on the constructivist viewpoint, which undertakes the idea of understanding, as well as reconstructing the constructions, which people initially hold (including the interviewer), thereby, aiming towards a consensus, yet opening up to new forms of interpretations, when improving on information and sophistication (Silverman, 2016). This research opted for qualitative research, because it provides a deep understanding of various social settings, as well as behaviours, from the participants’ viewpoints. Notably, an in-depth, and also a face-to-face interview method provides an interviewer with an opportunity of accessing a participant’s mental world, in a bid to having a glimpse of the logic by which the participants view the world, taking into account, the participant’s life world, thus expanding on his or her pattern of daily experiences (Flick, 2018). Based on the framework of this research, a series of questions will be posed to the participants and they will involve the following subjects: inspirations on fashionability, creative design process, professional development experiences, fashionability industry patterns, online shopping of fashionable items, fashionability index, as well as individual experiences that relate to fashionability.

3.2.1 Sampling

The sampling was based on two categories; the consumers (women) and the fashion designers, in order to get their perceptions on women fashionability. In this regard, designers’ responses were used in expounding on the concept of fashion trends, fashionability index, and fashion cycle. On the other hand, consumers’ responses aided in establishing grounds on the perception of fashion inflation, online shopping of fashionable items, and how it affects their choices.

Focus group 1:

A sample of 40 female college students were gathered to provide their perceptions on fashionability, and this included their knowledge of fashionable items and their online purchasing behaviour. Because of the issue of fashionability and online shopping are not new terms to young female adults, sufficient data was collected from these individuals to aid in the overall analysis of their perceptions. A random selection was done to participants aged 18 or older, and also who showed significant interest in fashionability or fashion items. They were provided with an incentive of free pizza, in order to enhance their participation.

Focus group 2:

The second focus group consisted of a sample of 12 designers who were recruited by use of purposive, as well as chain-referring sampling, which is sometimes referred to as snowball sampling (Buckland et al., 2015). Notably, purposive sampling poses as a non-probability-based procedure of sampling, which involves the selection of elements by the judgement of the researcher on which elements that would significantly facilitate the investigation (Etikan et al., 2016; cited in Emerson, 2015). The inclusion criteria for this sample included fashion designers having three and more years’ of experience, and presently working as professionals in any clothing company or who own their businesses. The time frame of three and above years of experience was used, in order to ensure sufficiency in fashion design experience, as it takes quite some years for a professional to be able to produce an extraordinary product.

3.2.2 Interviews

All the interviews were conducted through face-to-face in a particular research work station and café or library. There was flexibility, when it came to the rescheduling of meetings, by the availability of fashion designers, and students (consumers). Prior permission was obtained from the participants to record the conversations, which lasted for 45 to 60 minutes. It is worth noting that the length of the interviews only depended on the complexity, as well as clarity of the subject, which needed explanation, and the number of the interviewees on a given interview.

3.2.3 Structure of the interview

The purpose of using semi-structured interviews was majorly to aid in collecting in-depth information from the perspectives of the participants, regarding fashionability and issues related to it. At the beginning of the interview, both parties (the researcher and the participants) had a full introduction of themselves, in order to enhance trust and to provoke the thoughts of the participants (Lewis, 2015). The research opted for semi-structured interviews because there was a need to explore significant information, which is very subjective, and also developing, and to acquire the perspectives of the participants from different viewpoints. Also, semi-structured interviews provided the researcher with the opportunity of asking more questions, which aided in further developing significant knowledge regarding fashionability, fashionable items, online shopping of fashionable items and how they affected the choices of consumers. Using open questions aided in the evolution of new topics in the structure (Merriam & Grenier, 2019).

The interview questions were categorised into two sections. The first section was meant for fashion designers, where they were required to note their inspirations on fashionability; the creative design process (fashion trend and fashion cycle); their professional development experiences; the issue of fashionability index; and finally, their thought on the fashionable industry patterns. On the other hand, the second section was meant for consumers (college students) and they were required to answer the questions, which had the following subjects: their individual experiences that relate to fashionability; their perception on the measurability of fashion items, and finally, their idea on online shopping of fashionable items; how online shopping affect their choices.

3.2.4 Data collection procedures

The student participants (fashion consumers), they were recruited using flyers, which were posted around various known universities within the region. All the participants were provided with consent forms, in order to collect their demographic information. The researcher led this discussion by using questions, which were developed, based on the literature. The conversations between the participants and the researcher were significantly recorded and later transcribed (Smith, 2015). The information that was obtained from the interviews, as well as observations, were notably collected over 10 weeks. Overall, it is significant to take note of the fact that interviews entail strengths, as well as weaknesses. In this regard, in a bid to overcome the limitations in the lengthy interviews, observations, as well as the informations gathered from the participant, it is evident that magazines, reviews, and also videos that were published earlier on were examined, in order to provide the perspectives of the work of fashion designers, and also the perspectives of consumers on fashionability (Taylor et al., 2015). Moreover, in-depth, and also lengthy interviews aided in providing insights with regards to the thoughts, as well as feelings of consumers and fashion designers regarding fashionability. Notably, adopting long interview aiding in understanding the broader context of the professionalism of fashion designers and the industry that they operate in and the ideas that consumers had on fashionability (Bryman, 2016).

3.2.5 Data collection

The researcher piled and sent out a list of various semi-structure questions before the meeting, in order for the participants to think about the responses that they could provide beforehand. The researcher then met with the participants at a research work station, after they had shown their willingness to participate and share significant information for the research (Roulston, 2016). Notably, eight fashion designers were interviewed at the workstation, and the remaining four were interviewed in other quiet areas such as café or library. Moreover, 18 consumer participants were interviewed at the research work station, whereas 12 of them were interviewed in a café. The interviews lasted for three days, where the researcher took short breaks and interviewed participants for 45 to 60 minutes. This time depended on the speaking rate of the participants. Notably, each interview conversation was recorded digitally using a voice recorder and either with an Ipad or iPhone.

In the beginning, the participants were requested to sign the informed consent form, where they were asked to fill in a personal data form, which included significant information on the background of the participants and their demographic information. In this regard, the researcher inquired from the participants about their background and this included information on their education, as well as vital life experiences that made them be interested in fashion (Edley & Litosseliti, 2018). A significant fact behind introducing the participants with background information was to establish a significant rapport between the participants and the researcher because the participants might then be willing to open up on their personal, as well as sensitive information when a measure of trust has been established at the beginning.

Additionally, secondary data was also collected in this study. The researcher used fashionability index as well as the methods used by ONS regarding fashionability in clothing. The focus here was on selecting an area where fashionability was short lived. To collect such data, emphasis was put on using different indices; and attention was paid towards replacement in relation to key characterstics, colour, fabric, etc.

3.3 Data Analysis

The data retrieved from the interviews were analysed using the approach of grounded theory. The grounded theory provides a way for researchers to learn more about the world, by providing a theory that can aid in understanding it. Into detail, data were analysed using a constant comparison qualitative analysis method. This is an inductive approach that allows flexibility when it comes to generating the theory that emerges from the data content that is collected from a pre-existing theory (Glaser & Strauss, 2017). In a bid to analysing data, all the interview conversations that were recorded were significantly transcribed into a document in Microsoft Word. The researcher then identified the concepts, as well as categories derived from the data. The following step of the analysis was condensing and also dividing these initial categories into significant themes, purposely for coding.

As coding continued, various concepts were compared to others, and they were established into emerging themes. Notably, themes were developed into the significant coding guide, in order to enhance an open coding for the entire set of data. In the process of the axial coding, the researcher purposed to identify the patterns, as well as relationships existing across various themes of the data. The categories were analysed, and the themes were compared to the pre-existing literature, in order to come up with “dialectical tacking” that provided insights, interpretation, linkages, as well as thematic patterns, before work and also literature (Glaser & Strauss, 2017). By use of a constant comparative approach, the researcher purposed to tack back and forth in multiple transcripts, theory, as well as previous research, in finding patterns of various meanings present in data, and also the interpretation of the data.

3.4 Limitations

It is significant to note that this study has various limitations. The first is that small sample size has been used, yet a larger sample size could have provided more accurate results. Moreover, another limitation that is noted is that literature review that had been done previously on the measurability of fashionable items are few, yet more of scholarly articles could assist in providing the foundation for the research in building significant research objectives, and tackling the research problem effectively (King et al., 2018).

3.5 Ethical issues

The following ethical issues were considered in this study. First, there was informed consent, whereby, all the participants knowingly, and voluntarily agreed to participate in the study. Moreover, confidentiality and anonymity were given utmost consideration, in order to respect the dignity of the participants. In this regard, there was no requirement that they should disclose any of their personal information. Moreover, all the interviews were discarded after analysis, in order to prevent any third party from accessing them (Bryman, 2016).

3.5 Conclusion

From the above, it is evident that a collection of data, based on the perspectives of the consumers and fashion designers using qualitative research methods, would assist in further analysis and discussion. Grounded theory approach would assist in coding the themes, thus assisting in formulating a discussion for this research paper. Overall, it is evident that this section provides sufficient methodological information for this research.

References

- Blackie, R., Taylor, D., & Linacre, A. (2016). “DNA profiles from clothing fibers using direct PCR.” Forensic science, medicine, and pathology, 12(3), 331-335.

- Brannon, E. L. (2010). “Fashion forecasting.” New York, NY: Fairchild Books.

- Bryman, A. (2016). “Social research methods.” Oxford university press.

- Buckland, S. T., Rexstad, E. A., Marques, T. A., & Oedekoven, C. S. (2015). “Distance sampling: methods and applications.” (p. 277). New York, NY, USA: Springer.

- Cillo, P., De Luca, L. M., & Troilo, G. (2010). “Market information approaches, product innovativeness, and firm performance: An empirical study in the fashion industry.” Research Policy, 39(9), 1242-1252.

- Cooper, S., & Slobodkin, M. (2018). “U.S. Patent No. 9,858,611.” Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2016). “Capturing consumer engagement: duality, dimensionality and measurement.” Journal of Marketing Management, 32(5-6), 399-426.

- Echevarria, G. A., Bolufer, D., Torrens, M., & Nieto, S. (2016). “U.S. Patent No. 9,479,577.” Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Edley, N., & Litosseliti, L. (2018). “Critical Perspectives on Using Interviews and Focus Groups.” Research Methods in Linguistics, 195.

- Emerson, R. W. (2015). “Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling: How does sampling affect the validity of research?” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 109(2), 164-168.

- Entwistle, J. (2015). “The fashioned body: Fashion, dress and social theory.” John Wiley & Sons.

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T., & Bonsón-Fernández, R. (2017). “Analysing online purchase intention in Spain: fashion e-commerce.” Information Systems and e-Business Management, 15(3), 599-622.

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). “Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling.” American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1-4.

- Fenimore, R. D. (2018). “U.S. Patent No. 9,990,663.” Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Ferraro, C., Sands, S., & Brace-Govan, J. (2016). “The role of fashionability in second-hand shopping motivations.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 32, 262-268.

- Fischer, D., Böhme, T., & Geiger, S. M. (2017). “Measuring young consumers’ sustainable consumption behavior: development and validation of the YCSCB scale.” Young Consumers, 18(3), 312-326.

- Fletcher, K. (2013). “Sustainable fashion and textiles: design journeys.” Routledge.

- Flick, U. (2018). “An introduction to qualitative research.” Sage Publications Limited.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). “Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research.” Routledge.

- Godart, F. C., & Galunic, C. (2019). “Explaining the Popularity of Cultural Elements: Networks, Culture, and the Structural Embeddedness of High Fashion Trends.” Organization Science. 4(2), 116-130.

- Grant, K. (2015). “Knowledge management: an enduring but confusing fashion.” Leading Issues in Knowledge Management, 2, 1-26.

- Hines, T., & Bruce, M. (2007). “Fashion marketing.” Routledge.

- Kawaf, F., & Tagg, S. (2017). “The construction of online shopping experience: A repertory grid approach.” Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 222-232.

- Kennedy, A. M., Kapitan, S., Bajaj, N., Bakonyi, A., & Sands, S. (2017). “Fast fashion: A wicked problem for macro-social marketing.” Routledge.

- Khan, N. (2017). “Intervening Fashion: A Case For Feminist Approaches To Fashion Curation.” Fashion Curating: Critical Practice in the Museum and Beyond, 151.

- King, N., Horrocks, C., & Brooks, J. (2018). “Interviews in qualitative research.” SAGE Publications Limited.

- Lewis, S. (2015). “Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches.” Health promotion practice, 16(4), 473-475.

- Lion, A., Macchion, L., Danese, P., & Vinelli, A. (2016). “Sustainability approaches within the fashion industry: the supplier perspective.” Taylor & Francis.

- Lipovetsky, G. (2017). “The empire of fashion: Introduction.” Routledge.

- Liu, Y. J., Janssens, G. E., Kamble, R., Gao, A. W., Jongejan, A., van Weeghel, M., ... & Houtkooper, R. H. (2018). “Glycine promotes longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans in a methionine cycle-dependent fashion.” bioRxiv, 393314.

- Macchion, L., Da Giau, A., Caniato, F., Caridi, M., Danese, P., Rinaldi, R., & Vinelli, A. (2018). “Strategic approaches to sustainability in fashion supply chain management.” Production Planning & Control, 29(1), 9-28.

- McLeod, S. (2007). “Maslow's hierarchy of needs.” Simply Psychology, 1.

- Merriam, S. B., & Grenier, R. S. (Eds.). (2019). “Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis.” Jossey-Bass.

- Niinimäki, K. (2013). “Sustainable fashion: new approaches.”Aalto University.

- Niinimäki, K., Pedersen, E. R. G., Hvass, K. K., & Svengren-Holm, L. (2015). “Fashion industry and new approaches for sustainability.” Routledge.

- Noh, M., Carroll, J., Holt, S., & Blaser, K. (2017, July). “Fast And Slow Fashion Brands In Developing Sustainable Fashion: Aspect Of Fiber Materials.” In 2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna (pp. 439-444).

- Okonkwo, U. (2016). “Luxury fashion branding: trends, tactics, techniques.” Springer.

- Peng, L., Liao, Q., Wang, X., & He, X. (2016). “Factors affecting female user information adoption: an empirical investigation on fashion shopping guide websites.” Electronic Commerce Research, 16(2), 145-169.

- Roulston, K. (2016). “Issues involved in methodological analyses of research interviews.” Qualitative Research Journal, 16(1), 68-79.

- Shephard, A., Pookulangara, S., Kinley, T. R., & Josiam, B. M. (2016). “Media influence, fashion, and shopping: a gender perspective.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 20(1), 4-18.

- Shin, E., & Damhorst, M. L. (2018). “How young consumers think about clothing fit?” International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 1-10.

- Silverman, D. (Ed.). (2016). “Qualitative research.” Sage.

- Singh, G., Pratt, G., Yeo, G. W., & Moore, M. J. (2015). “The clothes make the mRNA: past and present trends in mRNP fashion.” Annual review of biochemistry, 84, 325-354.

- Skov, L., & Melchior, M. R. (2008). “Research approaches to the study of dress and fashion.” Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, 10.

- Smith, J. A. (Ed.). (2015). “Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods.” Sage.

- Spragg, J. E. (2017). “Articulating the fashion product life-cycle.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 21(4), 499-511.

- Stone, E., & Farnan, S. A. (2018). “The dynamics of fashion.” Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Taylor, S. J., Bogdan, R., & DeVault, M. (2015). “Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource.” John Wiley & Sons.

- Verleye, K. (2015). “The co-creation experience from the customer perspective: its measurement and determinants.” Journal of Service Management, 26(2), 321-342.

- Vincent, A. (2017). “Breaking the cycle: How slow fashion can inspire sustainable collection development.” Art Libraries Journal, 42(1), 7-12.

- Zeugner-Roth, K. P., Žabkar, V., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2015). “Consumer ethnocentrism, national identity, and consumer cosmopolitanism as drivers of consumer behavior: A social identity theory perspective.” Journal of international marketing, 23(2), 25-54.

- Zhang, B., Cao, Z., Qin, C. Z., & Yang, X. (2018). “Fashion and homophily.” Operations Research, 66(6), 1486-1497.

- Blackie, R., Taylor, D., & Linacre, A. (2016). “DNA profiles from clothing fibers using direct PCR.” Forensic science, medicine, and pathology, 12(3), 331-335.

- Brannon, E. L. (2010). “Fashion forecasting.” New York, NY: Fairchild Books.

- Bryman, A. (2016). “Social research methods.” Oxford university press.

- Buckland, S. T., Rexstad, E. A., Marques, T. A., & Oedekoven, C. S. (2015). “Distance sampling: methods and applications.” (p. 277). New York, NY, USA: Springer.

- Cillo, P., De Luca, L. M., & Troilo, G. (2010). “Market information approaches, product innovativeness, and firm performance: An empirical study in the fashion industry.” Research Policy, 39(9), 1242-1252.

- Cooper, S., & Slobodkin, M. (2018). “U.S. Patent No. 9,858,611.” Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2016). “Capturing consumer engagement: duality, dimensionality and measurement.” Journal of Marketing Management, 32(5-6), 399-426.

- Echevarria, G. A., Bolufer, D., Torrens, M., & Nieto, S. (2016). “U.S. Patent No. 9,479,577.” Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Edley, N., & Litosseliti, L. (2018). “Critical Perspectives on Using Interviews and Focus Groups.” Research Methods in Linguistics, 195.

- Emerson, R. W. (2015). “Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling: How does sampling affect the validity of research?” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 109(2), 164-168.

- Entwistle, J. (2015). “The fashioned body: Fashion, dress and social theory.” John Wiley & Sons.

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T., & Bonsón-Fernández, R. (2017). “Analysing online purchase intention in Spain: fashion e-commerce.” Information Systems and e-Business Management, 15(3), 599-622.

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). “Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling.” American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1-4.

- Fenimore, R. D. (2018). “U.S. Patent No. 9,990,663.” Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Ferraro, C., Sands, S., & Brace-Govan, J. (2016). “The role of fashionability in second-hand shopping motivations.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 32, 262-268.

- Fischer, D., Böhme, T., & Geiger, S. M. (2017). “Measuring young consumers’ sustainable consumption behavior: development and validation of the YCSCB scale.” Young Consumers, 18(3), 312-326.

- Fletcher, K. (2013). “Sustainable fashion and textiles: design journeys.” Routledge.

- Flick, U. (2018). “An introduction to qualitative research.” Sage Publications Limited.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). “Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research.” Routledge.

- Godart, F. C., & Galunic, C. (2019). “Explaining the Popularity of Cultural Elements: Networks, Culture, and the Structural Embeddedness of High Fashion Trends.” Organization Science. 4(2), 116-130.

- Grant, K. (2015). “Knowledge management: an enduring but confusing fashion.” Leading Issues in Knowledge Management, 2, 1-26.

- Hines, T., & Bruce, M. (2007). “Fashion marketing.” Routledge.

- Kawaf, F., & Tagg, S. (2017). “The construction of online shopping experience: A repertory grid approach.” Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 222-232.

- Kennedy, A. M., Kapitan, S., Bajaj, N., Bakonyi, A., & Sands, S. (2017). “Fast fashion: A wicked problem for macro-social marketing.” Routledge.

- Khan, N. (2017). “Intervening Fashion: A Case For Feminist Approaches To Fashion Curation.” Fashion Curating: Critical Practice in the Museum and Beyond, 151.

- King, N., Horrocks, C., & Brooks, J. (2018). “Interviews in qualitative research.” SAGE Publications Limited.

- Lewis, S. (2015). “Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches.” Health promotion practice, 16(4), 473-475.

- Lion, A., Macchion, L., Danese, P., & Vinelli, A. (2016). “Sustainability approaches within the fashion industry: the supplier perspective.” Taylor & Francis.

- Lipovetsky, G. (2017). “The empire of fashion: Introduction.” Routledge.

- Liu, Y. J., Janssens, G. E., Kamble, R., Gao, A. W., Jongejan, A., van Weeghel, M., ... & Houtkooper, R. H. (2018). “Glycine promotes longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans in a methionine cycle-dependent fashion.” bioRxiv, 393314.

- Macchion, L., Da Giau, A., Caniato, F., Caridi, M., Danese, P., Rinaldi, R., & Vinelli, A. (2018). “Strategic approaches to sustainability in fashion supply chain management.” Production Planning & Control, 29(1), 9-28.

- McLeod, S. (2007). “Maslow's hierarchy of needs.” Simply Psychology, 1.

- Merriam, S. B., & Grenier, R. S. (Eds.). (2019). “Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis.” Jossey-Bass.

- Niinimäki, K. (2013). “Sustainable fashion: new approaches.”Aalto University.

- Niinimäki, K., Pedersen, E. R. G., Hvass, K. K., & Svengren-Holm, L. (2015). “Fashion industry and new approaches for sustainability.” Routledge.

- Noh, M., Carroll, J., Holt, S., & Blaser, K. (2017, July). “Fast And Slow Fashion Brands In Developing Sustainable Fashion: Aspect Of Fiber Materials.” In 2017 Global Fashion Management Conference at Vienna (pp. 439-444).

- Okonkwo, U. (2016). “Luxury fashion branding: trends, tactics, techniques.” Springer.

- Peng, L., Liao, Q., Wang, X., & He, X. (2016). “Factors affecting female user information adoption: an empirical investigation on fashion shopping guide websites.” Electronic Commerce Research, 16(2), 145-169.

- Roulston, K. (2016). “Issues involved in methodological analyses of research interviews.” Qualitative Research Journal, 16(1), 68-79.

- Shephard, A., Pookulangara, S., Kinley, T. R., & Josiam, B. M. (2016). “Media influence, fashion, and shopping: a gender perspective.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 20(1), 4-18.

- Shin, E., & Damhorst, M. L. (2018). “How young consumers think about clothing fit?” International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 1-10.

- Silverman, D. (Ed.). (2016). “Qualitative research.” Sage.

- Singh, G., Pratt, G., Yeo, G. W., & Moore, M. J. (2015). “The clothes make the mRNA: past and present trends in mRNP fashion.” Annual review of biochemistry, 84, 325-354.

- Skov, L., & Melchior, M. R. (2008). “Research approaches to the study of dress and fashion.” Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, 10.

- Smith, J. A. (Ed.). (2015). “Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods.” Sage.

- Spragg, J. E. (2017). “Articulating the fashion product life-cycle.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 21(4), 499-511.

- Stone, E., & Farnan, S. A. (2018). “The dynamics of fashion.” Bloomsbury Publishing USA. Taylor, S. J., Bogdan, R., & DeVault, M. (2015). “Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource.” John Wiley & Sons.

- Verleye, K. (2015). “The co-creation experience from the customer perspective: its measurement and determinants.” Journal of Service Management, 26(2), 321-342.

- Vincent, A. (2017). “Breaking the cycle: How slow fashion can inspire sustainable collection development.” Art Libraries Journal, 42(1), 7-12.

- Zeugner-Roth, K. P., Žabkar, V., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2015). “Consumer ethnocentrism, national identity, and consumer cosmopolitanism as drivers of consumer behavior: A social identity theory perspective.” Journal of international marketing, 23(2), 25-54.

- Zhang, B., Cao, Z., Qin, C. Z., & Yang, X. (2018). “Fashion and homophily.” Operations Research, 66(6), 1486-1497.

Dig deeper into Rate of Depression in Thurrock with our selection of articles.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts