Expatriate Roles in Global Business

Chapter 1: Introduction

Background

Due to the rapid growth of foreign investment, multinational corporations (MNCs) have become more and more dependent on expatriates who can play a knowledge transfer role in global business environment. MNCs frequently send expatriates overseas with an aim of completing a specific assignment; the expatriates have to work and live for one year or more in this foreign country, and then return to their home country (Kraimer, et al., 2016).The overseas assignment requires expatriates with a good understanding of the local cultures,workforce environment,businesstrend,local government policies,etc. Quite often the expatriates have to face uncountable difficulties related to adapting themselves into a new culturalenvironment.In reality, most MNCs have high-failure rates of their expatriate overseasassignments, If the individuals cannot meet the task requirement for their overseas jobs, the failure rate can be very high(Tahir, 2018). Expatriates from parent-country nations areoften the employees of the MNCs’ headquarters.They are very important because most MNC operate their oversea subsidiaries by using expatriation. The definition of expatriates is “an employee of a parent company who is transferred for a particular amount of time (for several months to several years) to work in a branch of an international company located abroad” (Banerjee, Gaur, & Gupta, 2012).MNCs send expatriates as the agents of knowledge transfer from headquarters to subsidiaries or from subsidiaries to headquarters (Musasizi, et al. 2016).Expatriates failure has always been very high due to their poor overseas performance or the failure to adjust themselves into the host country culture. A wide range of research has shown just how significant it could be for expatriates to complete their overseas assignments given other critical extenuating factors such as adjusting themselves into new cultures, language, beliefs, behaviour, environment, lifestyle, governance, and developing a deep understanding of managerial effectiveness as well as decision-making process in accordance to their roles. The expatriates’ jobs have always been a popular research area for both MNCs and host countries. Studies have shown existence of many expatriates who could not complete their overseas assignments and choose to return early or did not have good job performance (Awais et al., 2013; McGinley, 2008). The high failure rate and the high costs related to this makes training become more and more necessary (Peng, 2018).

Looking for further insights on Modern Business Challenges? Click here.

Assigned expatriates aim to work in subsidiaries of their home country organizations overseas, research shows their motivation of doing oversea assignments normally is for their own career development as well as their company’s development (Bolino, 2007; Edström & Galbraith, 1977; Stahl et al, 2002). Another research indicated expatriates’ career progression is far faster compared to non-expatriates (Doherty, & Dickmann, 2012). Moreover, national economies acquire benefits, and in the longer term, upon repatriation, so do the home countries. Expatriates bring experience, skill, and competencies to the host country, enriching local stakeholders. Individually, they gain opportunities of further experience, learning and career progress, and financial benefits. Upon returning home the expatriates bring back improved competencies and cultural intelligence, and inject further financial gains into their home country economy. Therefore, a successful expatriate oversea assignment is particular valuable for multinational companies. This highlights my motivation to do the research with the aim of unveiling ways of making expatriates successful. In addition, while expatriates themselves may have a good adjustment in the foreign country, family-related problems can also lead to expatriate failure.Inadequate training or preparations before the deployment has also been known to cause significant expatriate failure(Tahir, 2018).There are high costs related to expatriate failure and repatriate turnover (Witting-Berman &Beutell, 2009).Thefailure not only costs MNCs money and lots of market share, but also damages the MNCs reputation and image(Wang,2008).According to the survey conveyed by GMAC Relocation Trends, roughly 21 per cent of expatriates left their companies during the assignments and another 23% left within one year after the repatriation from their assignments. Statics show that the cost of each expatiate failure is between 250.000 USD and 1.000,000 USD.An unsuccessful overseas assignment can cost roughly 100.000 USD(Misa et al., 1979). However, thishas not stopped the growth of expatriation. Over 80% of MNCs already successfully sent expatriates all over the world,the expatriate number constantly increase over the years(Black &Gregersen, 1999).GMAC Relocation Trends survey has also found that 68% of MNCs insist relocating their expatiate employees oversea despite the slowing economy(Deresky, 2011).In addition,there is a positive trend:54% of the expatriates have being occupied by younger age group, which is 20 to 39 years old.Meanwhile,the number of female expatriateshas also grown over the years,from 15% to 21%(Ball et al, 2010; Haile et al, 2010). While this is a positive development, it is still limited given that there are more than 40% of the global workforces occupied by female employees; only 22% have been given expatriate assignments(SHRM, 2014).

So,whatexactly is expatriate failure?The failure normally described as “a premature return”,which could mean one not finishingoverseas assignment before the end of the contract, or it could be poor performance and adjustment issues (Forster ,1997).The expansion of expatiate failure could be retention during the overseas assignment as well.A wide range of factors can be highlighted to explain expatriate failure. Mendenhall and Odour (1985) suggest that HR should not compare the domestic performance with overseasperformance given the two are not the same concept. Expatriate failure can have a wide-ranging impact on both the company and the employee. In terms of impact on the company, there are both direct and indirect costs to consider. Direct Costs of expatriate failure pertain primarily to the relocation costs of both the employee and their families, including airfares and shipping costs. Neumann (1992) estimates the direct cost per assignment for U.S. multinational expatriates who return early to lie between USD 55,000 - 150,000 (Naumann, 1992). Indirect costs primarily include loss of productivity both in terms of underperformance whilst on overseas assignment and the days occupied with relocating. Indeed, indirect costs associated with expatriate failure often exceed estimated direct costs (Ashamalla & Crocitto, 1997; Harvey, 1985). In terms of impact on the employee, failed assignments can be damaging to the employee’s physical and mental well-being due to low self-esteem, loss of prestige and respect among colleagues, weakening of the psychological contract, family issues, damage to an employee’s career path including reduction of promotion opportunities (Cuzzo et al.1994; Shaffer et al. 2006; Varner & Palmer 2002). The insufficient preparation before departure results in the high failure rate, in addition, inappropriate training and selection, lack of enough support and family issues can lead to expatriates failure as well. Statistics shows there are over 57% ofexpatriates fail because they are incapable of adapting into the new environment(Olsen & Martins, 2009).In other words,MNCs did not provide professional training (Wild, 2012).Language barrier could also be a big problem,misunderstanding the culture often results in the failure. As for the expatriates with families, success relies on the family adjustment as well, so the family members also should be included in the pre-departure training activities.Infact,as for them, if the family failed to adapt,they may return earlier (Shaffer & Harrison, 2006). Therefore, family issues should be practically considered in the selection process of the expatriates (Wild, 2012).

Aim and Objectives

This study will attempt to show what other researchers have done in terms of the reasons and conflicts resulting in expatriate failure, what the possible solutions they discovered in order to increase the successful rate of expatriation.

Objectives of the study

To critically evaluate literature on expatriation, expatriate failure, effect of cultural and environment change to expatriate, and concepts on expatriation

To investigate the negative outcome and influence of expatriate failure

To conduct interview and questionnaire examining the causes of expatriate failure and Human Resource departments’ strategies to increase successful rate of expatriation

To appraise the findings and make founded recommendation on expatriation failure and appropriate steps to be taken to increase success rate

Summary

In today’s global economy, many multinational companies send their managers and executives abroad as expatriates in order to obtain the skills, knowledge and information they need to help the company grow and develop. However, there is commonly a high rate of expatriate failure among overseas assignments. Scholars discovered some of which include challenges of adjustment in overseas environment, family issues, different policies, and conflicts have highlighted a wide range of reasons for these failures.Meanwhile,many HR strategies have been suggested in the existing literature concerning increasing expatriate success, these include emphasis on cross-cultural training, improving expatriate selection process and developingsufficient support during their oversea assignment.The overall purpose of this study is to examine whether the reasons and strategies in the existing literature is still suitable in today’s economy.

Chapter 2 Literature Review

Expatriation failure

Context and Dimension of National Culture

Failures in international business remain accentuated by companies whose cross-border managers failed to fully comprehend the context and dimensions of the national culture of the host country they work in (Carlson, 2013; Commisceo Global, 2016a). National culture relates to a framework of unique rules, models, customs, traditions, assumptions, and beliefs attributable to a specific country (Vinken et al., 2004) that serves as host to another country’s investment or business. According to Geert Hofstede, a renowned Dutch scholar and social psychologist, culture is “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” (Hofstede, 1980, p.21). As Hofstede averred, there are six dimensions of culture. First, power distance covering. degree to which uneven distribution of power is accepted by the less powerful societal units. Secondly, individualism vs. collectivism outlining degree of interdependence among members of society. Third, masculinity vs. femininity embodying distinction of emotional indices between men and women. Forth, uncertainty avoidance described as extent to which society treats unknown situations. Fifth, long-term vs. short-term orientation entailing how society links with the past as it engages present and future opportunities and challenges; and, lastly, indulgence vs. restraint covering the situation of being gratified or exercising control over human desires (Hofstede Insights, 2019). While Hofstede’s treatise on dimensions of culture has many critics, it is, nonetheless, considered one of the most extensively used references (Sondergaard, 1994), with profound application in the fields of business, marketing, and global trade, including cross-cultural training of expatriates before or during any foreign assignment (Taras, Steel, & Kirkman, 2012). Any organization that fields expatriates with inferior cross-cultural training or knowledge stands to encounter business difficulties because such omission causes significant financial losses (Fromowitz, 2011); impedes intercultural understanding, communication, and cooperation, apart from vitiating trust-based, competence-driven workplace relationship (Shockley-Zalabak, 2002). Moreover, blocks the exercise of host country-defined business strategies and policies (Talpau & Boscor, 2011); and erodes brand equity and reduces brand value in the host country where unqualified or untrained expatriates operate (Ko & Yang, 2011; Meyer, 2015).

Cultural Dimension of Individual Behaviour and Performance

As Erez & Gati (2004) propounded, culture is a multi-level construct that engenders a structural dimension pertaining to a hierarchy of cultural tiers where the individual, as the core or innermost element, is nestled within groups, communities, organizations, countries, and the global culture. Culture also develops a dynamic dimension, which concerns relationships and engagements among different levels of culture in a way by which they impact one another. Erez & Gati averred that culture has five levels, as shown Figure 1 illustrating the multi-level cultural paradigm. As national culture impinges upon organization culture (Etgar & Rachman-Moore, 2011; Gerhart, 2008), with the latter impacting on the group culture and ultimately the individual, the influence of national culture on the values, sentiments, feelings, beliefs, and aspirations of people in one country, expatriates included, becomes evident and not difficult to appreciate (Earley, 1994; Erez & Gati, 2004; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). By way of amplification, organizational culture, as defined by Schein (1990, p. 5), is: A pattern of basic assumptions formulated and adopted by a group of people, as the group acquires coping skills in addressing problems of external adaptation and internal integration that has proven useful and valid to be endorsed to new members as the correct way to perceiving, thinking, and feeling with respect to the relevant problems.

Based on the context of the bottom-up direction, where the individual remains the key actor, the dynamics of the cultural transition highlight the cardinal importance for the individual to be aligned with the context and dynamics of the host country culture (Alutto, 2002; Soares et al., 2007). This alignment is justified by the following realities: (1) global culture engages the national culture of host country; (2) national cultural factors, and not global, directly influence the context of organizational culture; (3) the organization may accept or reject national cultural dimensions; (4) if the organization rejects national cultural dimensions, a serious dichotomy or disconnect emerges between the organization and group/individual behaviour, with the onset of culture shock on the part of an expatriate employee being one observed outcome (Naeem, Khan, & Nadeem, 2015); and (5) if the organization embraces the national culture dimensions, cross-culturally compliant behaviours and strategies evolve at the individual level (Kotler, 2001; Kotler & Armstrong, 2012), while expatriate employees demonstrate innovative performance, marketing propensity, customer-centric priorities, and positive learning attitude (Soares et al., 2007) – thus reinforcing the importance of cross-cultural training of expatriates. According to Black et al(1991), ‘the greater cultural distance is, the more problem to adjust.’ Cultural distance means the difference between native culture and host country culture, in terms of attitudes, values, behaviours and customs (Reus & Lamont, 2009; Selmer et al. 2007). Such cultural barriers could affect an expatriate’s well-being and performance, which could in turn lead to expatriate failure. Researchers suggest that the conflicts often happen when the interaction between different cultures, as people from different culture background tend to have different communication dimensions(Kegan et al.1982; Ting-Toomey,1986).For example, people who from an individualistic culture tend to have a direct communication style. In contrast, people who from a collectivistic culture background often use an indirect and avoiding way to make a conversation (Lee & Rogan, 1991;Ting-Toomey, 1991).

Take an example of conflict between Japanese managers and Thai employees. Japanese think that a member of the company is like a member from his family and should be provided particular attention and caring. However, after the interaction, Japanese manger will look down Thai staff, because there is a significant hierarchy in Thailand(Pongsapich, 1998).Also, Thai staff have a very negative impression of Japanese managers because they think it is appropriate for managers to keep distance from employees( Swierczek&Onishi, 2003) Most companies provide brief training to introduce the host country’s culture, however oftentimes this is not sufficient. The cost of providing training is often cited by firms as a reason for not providing training. For example, American companies typically do not provide expatriates with cross-cultural training due to the cost of providing it, as they worry that employees may leave the company and as such, they are reluctant to invest a large amount of money on cross-cultural training programs. However, Bateman and Snell(2004) show that lacking of knowledge of host country culture is the major cause for expatriate failure, with many expatriates struggling to overcome cultural barriers. Moreover, lack of or insufficient language training can further lead to Expatriate Failure (Peltokorpi, 2010; Selmer, 2006). Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al. (2005) further suggested that language competence contributes to both work and cultural adjustment. The reason for this is that language is an essential tool to help expatriates understand the new culture (Selmer & Lauring, 2014).

Psychological Contract

Psychological Contract refers to the implicit perception of obligations between an employer and employee from both the perspective of the employer and employee and is particularly important for expatriates. Not only does the psychological contract in effect double with an overseas assignment because expatriates have a dual psychological contract with both their native country company and also with their host country’s company, but psychological contract is particularly important as when on overseas assignment, the relationship with the employer is of vital importance because expatriates are typically exposed to more risks than when in their home country. Moreover, Haslberger & Brewster (2009) identified 3 different bases of psychological contract for expatriates: upon accepting the overseas assignment, upon moving overseas to start the assignment and finally, upon repatriation to the home country. Therefore, an overseas assignment makes it much easier for breaches of the psychological contract to occur, resulting in a higher rate of psychological contract breach for expatriates compared with domestic workers. Further, Turnley and Feldman (1999) found that breach of psychological contract has a deep negative influence on employee attitudes and performances. Thus once psychological contract breach has occurred, the early repatriation of expatriates will happen, resulting in expatriate failures ( Cole&Nesbeth, 2014).

Expatriate’s personality

An expatriate’s personality plays an important contributing factor to their success on an international assignment. Researchers have commonly identified key personality traits that contribute to the success or failure of an international assignment, including extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness. Extroversion can help form social relationships in a new overseas environment, agreeableness indicates an expatriate’s willingness to cooperate, conscientiousness indicates an expatriate’s reliability of work and commitment and openness indicates an openness to new ideas on an international assignment. Personality even often plays a more important role in the success or failure of an expatriate assignment than technical competence (Stone, 1991). Stone (1991) identified 10 criteria important in expatriate selection including: Ability to adapt, technical competence, spouse and family adaptability, Human Relations skills, desire to serve overseas, previous overseas experience, understanding of host country culture, academic qualifications, knowledge of language and understanding of home country culture. Nevertheless, all too often, personality is neglected in the selection of overseas candidates resulting in expatriate failure. For example, if an expatriate is unable to form social relationships in a new overseas environment, this is likely to have a direct impact on their enjoyment overseas meaning the expatriate is likely to want an early return to their home country, leading to expatriate failure. Moreover, lack of enjoyment and social integration in host country can even have a knock on impact on the expatriate’s productivity and quality of work, thus also leading to expatriate failure.

Family

Family issues often post a huge challenge in successful overseas assignments and are often cited as the main reason for the premature return of the expatriate and therefore expatriate failure (Trompetter et al 2016). Not only does an expatriate need to consider himself or herself, but also spouses, children, and even elderly parents need to be considered. Indeed, research indicates that typically family accompanies at least 70% of expatriates. Expatriate failure resulting from family issues can be multi-faceted. One example is that if an expatriate relocates with their spouse, their spouse’s career may be interrupted, potentially resulting in the career that they worked very hard to obtain being wasted. In addition, relocation may result in the loss of a spouse’s income. Both these factors could lead to the spouse’s identity within the family will becoming unclear and uncertain and thereby resulting in the reduction of self-esteem and increased psychological withdrawal (Schlenker and Gutek 1987). In turn, this can directly contribute to expatriate failure (Cole,2011). Another explanation of expatriate failure resulting from family issues is linked to Family Systems Theory (Trompetter et al 2016). Family Systems theory asserts that the family is an open socio-cultural system and therefore if one family member is on an expatriate assignment, it can affect the balance within the socio-cultural system due to added stress from the expatriate assignment. Expatriate failure resulting from family issues can further be explained by Spillover Theory (Trompetter et al 2016). Spillover is described as the transfer of moods, skills, values and behaviours from one role to another and in this context, it can be viewed as experiences at home may spillover to the performance levels at work and vice versa. Therefore, even if the expatriate has successfully adjusted to the new environment, if his/her family is finding it more challenging, this may impact the expatriate’s performance on the assignment. Furthermore, if the expatriate is struggling with the expatriate assignment, this may have a spillover effect on family life, affecting the family’s ability to fully adjust and integrate into the new environment. In turn, both these factors can lead to expatriate failure.

Conflicts

Expatiation often failed due to variety of conflicts occurred during the expatriates oversea assignments.

Different perspectives

Different perspectives on work ethic

Work ethic is different from country to country. Different perspectives on work ethic can cause conflicts between expatriates and local employees. For example, the American managers are used to work far more early before the deadlines. Even if they have spent a long time to complete the work, they are still willing to start early but finish late. Meanwhile, they are expect their colleges to do the same. However, working during individual personal time is seen as unsuitable for most European employees. For instance, an expatriate from the UK think the US workers are ambitious, conscientious and driven, which is very different with the British employees. Similarly, Japanese mangers often voluntarily work during the weekend. They insist that they have nothing to do at home during their weekend, they feel comfortable to do some work in the office and make them feel fulfilment. However, it is not understandable for Thai staff as they believe individual free time and relax( Swierczek&Onishi, 2003).

Different perspectives on decision making

American managers get frustrated and irritated about the length of accepting new ideas in the UK and Germany companies. Even if the ideas have already been proved to be effective in the US, they still constantly testing them. For instance, in Europe, the co-workers of the US expatriates tend to spend enormous time on decision making. The reasons they explained is they have to make sure the decision can be adopted and implemented from various of aspects.

By contrast, in America, employees are more likely to have it go instead of planning for a long time beforehand. They change the strategies during the process if there is any problems occurred. This type of conflict is related to the way of getting the result. the European workers have to think a lot before making decisions and taking actions, but the US workers hold the sense of “just doing it”. Another example would be Thai employees change their decisions from time to time, because they think it is sensible to adjust decisions depend on different environment. However, Japanese expatriates feel very irritated by constantly changing decisions made by Thai staff. They view this behaviour as not being serious and organized( Swierczek&Onishi, 2003)

Different perspectives on planning

Japanese expatriates have a long-term vision in terms of making plans. They require their Thai staff to follow the same time period to work for the future promotion or increasing of wage. However, Thai staff feel it is not necessary to waste current time for the uncertain future, so they are often quite reluctant to follow Japanese expatriates long-time scenario( Swierczek&Onishi, 2003)

Different perspectives on company’s policy/regulation

Lofe time employment and seniority are very common in Japan, they are viewed as the discouragement for staff by Thai employees. As lifetime employment provide lifetime position for employees, it is very easy to cultivate lazy staff. In addition, Thai employees also argue that those policies are very inflexible, because the economic nowadays change very fast, the company should react flexibly toward the change instead of continually applying lifetime employment and seniority wage system. Thai staff argue that the reward should based on performance instead of the lengthen of the employment. In this situation, Thai expatriates are very unhappy about the company policies made by Japanese mangers, they are very unwilling to adopt the change, which result in the conflicts. In addition, they think the Japanese mangers in the management position is because they are old but not because they have the real ability, they may do not recognize the mangers’ authorities, thus leads to the further conflicts. Thai staff are often very unhappy about the consensual decision making by Japanese managers, they argue that some Japanese mangers cannot speak a very good English, so they tend to only discuss with their own group and make decisions. Thai staff feel they are less engaged and less trust-worth in decision making. One case is about a laboratory technical staff have a serious conflict with an expatriate lecturer. The technician was dissatisfied about how frequent the lecturer breaking university regulations for lecturer’s personal benefit. The technician complained that the lecturer wanted to provide extra sessions to a certain group of students during the unopen hours of the laboratory, because those students often invited her for dinner. However, the key holder of the laboratory is the technical staff himself and he is responsible for watching the laboratory equipment. Therefore, the lecturer required the key from the dean based on the reason that the technician was not help her to operate the video and audio equipment, but according to the technician, in that occasions, the lecturer told him she was ill and was not able to attend. In addition, the technician suggest the lecturer was very unprofessional in the case of showing favouritism to the students who invited her for dinner at home. In the end, the technician argued that the university regulation is unchangeable .In contrast, the lecturer insist of changing the university system in order to make the teaching more efficient. The conflict had been leaded by the miscommunication and different interpretation. The technicians may feel the lecturer was disrespectful to the culture, regulation in the university. The lecturer may think the technician treated her unfairly because she was an expatriate.

Stereotypes

Stereotypes caused by the belief based on group membership(Katz and Braly, 1933, Fiske and Taylor, 1991, Wyer and Srull, 1989; Stangor, 2009,).It is a kind of perspective that the members from a specific group have the same characteristics which distinguished them from the people from other groups(Hogg and Abrams, 1988, Operario and Fiske, 2001).This belief may lead to the difficult relationship and conflicts from one group to another group. Negative stereotypes hold by one nation towards the other also lead to the conflict. For instance, the American expatriates in most countries have been seen as exploiting locals. Some expatriates even been viewed as the spy. The typical stereotype of Americans are arrogant, bossy, opinionated and tend to take the control. However, some countries are value listening, discussion, consensus. Many American expatiates found it is very hard to gain credibility for their ideas based on this stereotype. Local employees argue that the Americans think they are the best, they want to teach and instruct others and have a sense of superiority.

Ethnocentric management approach

Ethnocentric management approach also causes the conflict during the introducing headquarter policies. For instance, the US expatriates always face the difficulties when they apply the decisions made by the US headquarters, because the local staff constantly came up with their own procedures. Moreover, the local employees are suspicious of the decisions from the US all the time. They believe the same sensoria is worked in the US but nobody can guarantee it can be effective in other countries. To make the situation even more difficult, some local employees feel belittled by following instructions from an “outsider”, which even generate the resentment from local employees toward expatriates.

Politics

The politics also influence the relationship between expatriates and local employees. For example, after the bombing of the Chinese embassy, one expatriate in Hong Kong have to face the heated debate with his colleagues.

Ethical dilemmas

The conflicts occur not only based on the different legal systems but also based on some unclear laws. Expatriates have to worry about whether their actions break the legal boundary or not. Furthermore, bribery, corruption have been seen as illegal for American expatriates, but it is very common in some Asian countries and Latin American. American expatriates often struggle with the ethical dilemmas in those situations(Avan et al.2004).

Unequal treatment

Expatriates normally receive the rewarding, compensation and high social status in the host country(Bonache, 2006).They can get 2-5 times higher reward compared with the reward received by their headquarter colleagues(Chen et al. 2002; Schuler et al. 2002),and even more than 15 times more than that received by local employees in the subsidiary (Oltra,2013). Many HR practices in multi-national companies damage the relationship between expatriates and local employees. Especially Ethnocentric approach shows favourism to the expatriate, which makes local staff fell that they are less valuable than expatriates are. Consequently, local staff may generate hostility towards expatriates and view them as “outsiders”. The inequitable treatment leads to us-versus-them stereotypes, which could result in the further conflicts. In the selection process, headquarters think it is secure to send the expatriate to subsidiary instead of employing local manger. In the aim of control, parent companies like using their own nationals despite the fact that their own nationals may not be the most appropriate person in this position. As a result, the local employees fell they are not be trusted and have discontent over both headquarter and expatriate. A finding shows the young generation of managers in Singapore are discouraged by the constantly use of expatriate, which result in the high turnover rate in Singapore companies( Hailey ,1996) Moreover, Expatriates also get extra reward and higher wage than local staff. Although local employees are also qualified professionals(Welch 2003),expatriates received 20 to 50 times higher salary, rank (Chen et,al.2002)than them(Okeja,2017), which given the local employees a kind of feeling of being treated like “second class citizens when working alongside expatriates in their own country” (Toh & DeNisi 2005).

Coping strategies of expatriation failure

Training

Littrell et al. (2006) suggest the definition of Cross Culture Training would be an educative approach to improve intercultural learning, whilst developing the cognitive, efficient and behavioural competencies required for successful interactions in a variety of cultures. Moreover, Jie & Lang found that cross-cultural training could release the severity and period of culture shock and that a suitable cross-training program can help expatriates fit in the new environment and finish the tasks efficiently (Jie&Lang,2009). As failure narratives of culturally non-compliant international companies abound, with major brands playing central role in the commission of cross-cultural blunders (Commisceo Global, 2016b; Amirsan, 2018), the general perception on the importance of cross-cultural training and cross-cultural compliance among global companies gravitate toward appreciation and acceptance, especially for those who have gone through systematic and integral training (Bean, 2008; Selmer, 2018). Studies show that training and development of expatriates on the complexity and dynamics of cross-cultural training has achieved marked effectiveness. With the positive link between cross-cultural training and expatriate performance established, companies offering cross-cultural training to expatriate employees significantly increased from 30% to 60% over a period of 10 years (Tjitra & Jun, 2011). The Hamburger University, established by McDonald’s as a holistic training center for the overall effectiveness and cross-cultural competence of McDonald’s international managers, represents a concrete institutional evidence of contextualizing cultural dimension in expatriate training. In fact, the University has graduated no less than 80,000 restaurant managers, mid-managers, and owner/operators all over the world (McDonald’s.com, 2016). In line with properly empowering expatriates with the most useful and productive cultural learning information, carefully planned and winning training programs include socio-economic, political, and socio-cultural characteristics of the host country. The training content mix also encompasses religion, food, health system, and education to give the expatriate employee a good idea of the environment of assignment; language, interaction, didactic, and experiential training; family adjustment, cultural awareness, and adaptability training; and cultural differentiation, which refers to upholding the host country culture while being connected with the native culture (Tjitra & Jun, 2011; Mulkeen, 2017; Diaz, 2018).Human Resource departments can offer Cross Cultural Training to expatriates both prior to and during the assignment.

Indeed, many European companies already offer cross-cultural training programs. For example, in the UK, there is a training facility called the Center for International Briefing at Farnham Castle. The training program offered comprises knowledge about British history, politics, religion and the economy. The methods which used to deliver the knowledge are a variety of lectures, audio-visual presentations and discussions. Other European centres also offer cross-cultural training facilities; for example: the Tropen Institute (the Netherlands), the Carl Duisberg Center, and Evangelische Akademie (both Federal Republic of Germany). Moreover, Japanese companies guarantee expatriates access to comprehensive and rigorous training programs before their overseas assignments. Not only do they send expatriates to train by their overseas offices for a year, but they also pay expatriates tuition, expenses and regular salary to complete post graduate study programs abroad. This allows expatriates from Japan to acquaint themselves with the new culture by observing it closely and personally participate in it prior to any formal expatriate assignment.

Support

It’s important to assess the strategies Human Resource departments can implement to reduce the risk of Psychological Contract breach embedded in an overseas assignment. Given Haslberger & Brewster (2009) identified the 3 bases of psychological contract breach, Human Resource departments should implement strategies to address these three bases and we will consider each base in turn. In order to mitigate psychological contract breach upon accepting the overseas assignment, expectations from both the perspective of the employer and expatriate should be level set and a formal contractual agreement should be executed which covers terms such as compensation, relocation, training, family etc. In order to mitigate psychological contract breach upon commencing the overseas assignment, it is vital companies offer ongoing support whilst on assignment. This could be provided in the form of a corporate sponsor in the expatriate’s home country, who is responsible for providing regular check-ins with the expatriate whilst on assignment and also for providing information and updates regarding the expatriate’s home office. This has the effect of making expatriates secure, so that they have a feeling that regardless of where they are located, their company and boss will always look after them. Ongoing support can also be provided in the form of a mentor in the host country who’s responsible for monitoring the wellbeing, progress and development of an expatriate whilst on overseas assignment (Tung,1987). Lastly, in order to mitigate psychological breach upon repatriation, Human Resource departments should ensure a robust and structured repatriation approach is in place to find an appropriate post for the repatriate to leverage their newly found skills, knowledge and experience back in their home country. A key component of the psychological contract upon repatriation is the expectation that the former expatriate will be able to put their newly acquired skills, knowledge and experience into place in order to ensure that the companies eventually benefit from the overseas assignment. Therefore, if repatriates do not feel this is the case, this can lead to breach of psychological contract and ultimately expatriate failure. Moreover, this expatriate failure can further be magnified if the repatriate shortly leaves their company a short time after repatriation resulting in the loss of the repatriates’ knowledge, skills and experience to the company (Yeaton&Hall,2008).

Selection Criteria

It’s of paramount importance that the expatriate selection process is expanded to also evaluate the personality traits identified as being important in an overseas assignment. Indeed Stone (1991) identified 10 criteria important in expatriate selection including: Ability to adapt, technical competence, spouse and family adaptability, Human Relations skills, desire to serve overseas, previous overseas experience, understanding of host country culture, academic qualifications, knowledge of language and understanding of home country culture. Of these ten criteria, many relate to personality traits namely: ability to adapt, human relations skills and desire to serve overseas. In order to evaluate these personality traits in the selection process, Human Resource departments should employ psychometric testing and thorough interviews in the selection process. In order to combat expatriate failure resulting from family issues and in view of the fact that family issues are often cited as the main reason for premature return of expatriates, it’s of vital importance to consider and incorporate family in all the Human Resource strategies we have looked at so far. For example, any cross-cultural and language training should not only be offered to the expatriate themselves but also to all their family on assignment too. Family should also be a key consideration in any of the strategies to mitigate breach of psychological contract. For example, any ongoing support offered on assignment should also be offered to the expatriate’s family. Moreover, the expatriate selection process should also be extended to the expatriate’s family to assess, for example, the whole family’s ability to adapt etc.

Minimize conflicts

Training

Expatriates

There are four stages of training which designed in order to help minimize conflicts thus increases the successful rate of expatriation. The first stage aims to prepare expatiates for cross-cultural encounters(Harris & Moran, 1991). This stage includes two steps: the first step is the self-assessments. This includes the self-assessment of change. If an expatriate is unwilling to adopt the change, it would lead lots of conflicts when they come into a brand new culture environment. The next step is to cultivate culture-awareness. The following stage is to help smooth interaction between expatriates and local staff. It is also contain two steps: the first step is to build the knowledge of local customs, language; the second step is to build an appropriate behaviour in the relevance of local environment. The first step give expatriates the information about the demographics, economy, geography climate, political system and history of their host country(Ronen, 1990).As a result, the empathy could be increased and improve the cross-cultural relationships(Tung, 1981).Once the relationship improved, the conflict will also be reduced.( Harrison, 1994).

Local employees

Obviously, the conflicts are caused by two parties, one is expatriate, another one is local employees. Training host country nationals for cooperating with expatriates reduce the discriminatory treatment that faced by expatriates( Sanchez et al. 2000). As I mentioned above, expatriates are often in the dilemma caused by stereotype , which prevented them to obtain credit. It is important not only place the training burden on expatriates to help them adapt and learn host country culture, it is also important to train local staff to respect expatriates. The local staff should be taught how to interact and collaborate with expatriates.

Selection Criteria

Emotional intelligence shows an important skill for expatriate to manage interpersonal and cross-cultural conflicts (Jassawalla et al., 2004).If headquarters pay attention to emotional intelligence and social skills when they select the expatriates. The expatriates they selected will overcome the conflicts caused by national stereotypes. Technical competence is a crucial criterion in the selection of expatriates, but it is not enough when it comes to adjustment (Sanchez et al., 2000). In order to minimize the conflict, selecting the expatriates with certain personality traits is very important (Caligiuri, 2000). This personality traits include sociability, openness (Caligiuri, 2000),the ability of tolerance and patience (Yavas & Bodur, 1999),the ability to adopt change and self-confidence (Forster, 2000).If in the selection process, Human Resources put the emphasis on personality traits and select the right expatriates, the interpersonal conflict between expatriates and local employees would be minimized. In order to deal with the conflicts caused by different culture backgrounds, managers should consider to select an expatriate with cultural intelligence. The concept of cultural intelligence is neither social intelligence or emotional intelligence, it includes four basic elements: cognitive facet, behavioural facet, motivational facet and meta-cognitive facet (Ang et al, 2006, 2007;Earley & Ang, 2003, Earley et al, 2006; Ng & Earley, 2006). The first element is the ability to seek the relevant knowledge of different cultures. The second element is the ability to copy the natural and proper understanding of gestures as well as behaviours. The third element is the motivation to learn and understand different cultures. The fourth element is the ability to reflect during the interaction with different cultures. People who have meta-cognitive quality are capable of adjusting, making plan and monitoring during and after the interactions(Ang et al. 2007).

Culture intelligence is a psychological feature(Przytuła, 2013). People who are cultural intelligent have the intention to experience new cultures, they are open to culture diversity and willing to experience other customs and other ways of living even than their own(Przytuła,2014). If we select the expatriates who are cultural intelligent, they not only have a good understanding of host country culture, but also reflect themselves during the interaction. Therefore, the cross-culture conflicts are unlikely to happen.

Coping strategies

The way the expatriate managers cope the conflicts is crucial in case of minimizing conflicts.For instance, they should have good listening skills. Good listening skills can lead to a better understanding and can minimize conflicts caused by miscommunication. Secondly, they should be positively engaged with the locals. For example, living with locals instead of living in “American Ghettos”. The flexibility is also important. For instance, the ability to think on one is fit, which means when conflicts occurred, they should take initiative to communicate with co-workers in order to understand what and why conflicts happened. For instance, an American manger became very patient during the interaction with Asian colleges. Because in Asian culture, directly talk business is regarded to be rude, people prefer spending longer hours to get familiar with each other first, like families and background.

Equal treatment

Nowadays, mutil-national companies are trying to change the unfair selection process and compensation/wage differences between expatriates and local employees. However, it is quite difficult to change because less compensation and payment will prevent the expatriates to take the oversea assignments. Because many companies do not have a thorough repatriation ,most expatriates have to worry about their career development once they return to their home countries. In addition, they may lost lots of promotion or career progress during their oversea assignment. As a result, If the companies do not offer a beneficial compensation packages to expatriates, expatriates will refuse to take the oversea assignments. In order to solve this problem, the mutil-national companies should improve their repartition system in order to attract expatriates in the situation of no extra wage/compensation benefits. Once the wage/compensation gap have reduced between expatriates and local employees, the resentment among local staff will also reduced, thus minimize the conflicts between expatriates and local employees.

Assignment length

Another method would be shorten the period of expatriate assignment. If the time of oversea assignment have reduced, muti-national companies do not need to pay a large amount of benefits to the expatriates. Consequently, minimize the unfair treatment between expatriates and local employees, meanwhile minimize the conflicts (Soo & Angelo ,2005). However, as for some assignments, which require long time expatriation, this method is inappropriate. In this kind of situation, applying other methods should be considered.

Overarching identities

Overarching identities can help to reduce intergroup hostilities. There are a couple of methods to create an overarching identity (Stets & Burke, 2000).The most traditional one is to get two groups together to deal with a common enemy (Ellemers, et al, 2004).That is because when two groups face another group, the dissimilarity from those two groups will be overcome. The negative stereotypes hold by host country nationals to expatriates will be neutralised and moderated. For instance, host country nationals and expatriates may have to cope with a picky boss or deal with difficult costumers. Another example would be in the situation of a merger or an acquisition. In those kind of situations, the host country nationals and expatriates are ally, partnership, which they are more likely to get closer. In fact, it is very often expatriates and local employees have to deal with a competitor of the company, so the conflicts between expatriates and local employees are unlikely to occur.

Chapter Summary

There is a relatively high expatriate failure rate which has many costly implications both on the expatriates themselves and the companies they work for. We have seen that this is caused by a variety of factors including lack of both cultural and language training, breach of psychological contract, personalities not suited to an overseas assignment and family considerations. Moreover, the conflicts between expatriates and local employees is regard as a big issue which caused the obstacles or even failure through expatriate oversea assignment , The conflicts between expatriates and local employees may caused by culture differences, the different perspective of work ethics, time, decision making, stereotypes hold by local staff toward to expatriates, the unfair treatment between expatriates and local employees from headquarter , different attitude about the ethical issues like corruption ,bribery, politics between different countries, ethnocentric management approach and different perspectives of the regulation in the subsidiary. However, these issues can be mitigated to some degree, if Human Resource departments implement appropriate strategies to combat these issues. Accordingly, the strategies discussed should be at the forefront of any international company’s Human Resource policies when offering and arranging expatriate assignments. Strategies such as Enhancing fair treatment, providing the proper training to both expatriates and local employees in order to minimize cross-cultural conflicts as well as negative serotypes. In the expatriate selection process, the personality and cultural/emotional intelligence of an expatriate should be the main criterial of selection. Expatriates themselves should be optimistic about the conflicts, and should be positively engaged in solution process when conflict occurred. Lastly, building overarching identities for expatriates and local employees also can minimize the conflict. Indeed any overseas assignment should be thoughtfully considered and planned to ensure the employee is suited to such an assignment and has the right support network and training in place to succeed and for both the employee and employer to reap the benefits of the overseas assignment.

Chapter 3: Methodology

Introduction

According to Ochsner, Hug and Daniel (2012), the purpose of a research study, especially one that takes into account primary study is to enable the development of new knowledge, as well as introduce new perspectives of thinking and reflecting on issues. This chapter entails a significant outline of the research methodologies, approaches, strategies, and techniques, which were used in the process of the study to conduct research, and produce sufficient results, related to answering the proposed research questions of this study. Herein as such is a sequential evaluation of the research design, philosophies, approaches, strategies, data collection and analysis, as well as sampling and ethical requirements appropriate to ensure that the selected approaches and procedures optimize a valid and valuable focus to answer the research questions and achieve its stated objectives. The selected approach minimizes the risk of human error in the collection and analyses of data phases.

Research Design

Kothari (2004) points out that the application of science in the various processes and activities concerned with a research study informs research methodology, Remenyi et al. (2003) highlights that a research design dictates the direction of the actual study as well as the manner by which the research is conducted. Saunders et al. (2009) further clarifies that a suitable research design needs to be selected based on research questions and objectives, existing knowledge on the subject area to be researched, the amount of resources and time available, and the philosophical leanings of the researcher. The research design dictates the types of strategies that a researcher can adopt for use in a study, some of which include survey, case study, experiment, action research, ethnography, archival research, grounded theory, cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies and participative enquiry (Collis and Hussey, 2009; Saunders et al., 2009).

For this study however, guided by the above principles, the researcher adopted the use of closed ended questionnaires and informal interviews. Griffiths, (2009) points out that the qualitative research design involves detailed exploration and analysis of particular themes and concerns within a topic. Further he highlights that that qualitative approaches are particularly useful when the topic of research is complex, novel or under-researched.As it leaves the results open to the possibility of unexpected findings, rather than predicting an expected outcome, as is often the case for quantitative research.

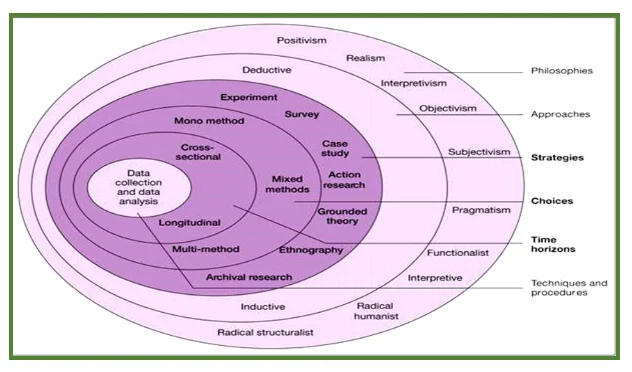

Philosophical paradigm

Based on the provision of the Research Onion Diagram (Saunders et al. 2007) as shown in Figure 2, this study will adopt a mixed methods research design, premised on a pragmatist philosophy (Saunders et al, 2007). The approach embraces aspects of the interpretivist philosophythat treats the world as a conglomeration of social constructions and meanings in human engagements and lived experiences (Daymon & Holloway, 2002; Gomm, 2008). The interpretivist paradigm works in dichotomy with the positivist model, which views the world as an embodiment of clarity, unambiguity, and verifiable reality that can studied only with total objectivity (Cavana et al. 2001). This study combines the rationalist and empiricist approaches and encapsulates concepts, theories, frameworks in explicating the different research concerns, including objectives, questions, phenomena, and behaviours (Abend, 2008; Swanson, 2013: Weick, 2014).

Research Method

While the diversity of research studies enables utilization of multiple applicable methodologies to gain both rich qualitative and quantitative data to fulfil the purpose and objectives of the study, often significantly specific studies require only one of these methods to effectively highlight the research outcomes. Essentially qualitative and quantitative data provides researchers with opposing perspectives in a study. While Qualitative data is a dynamic and negotiated reality that seeks a human behaviour perspective, quantitative data is a fixed and measured approach to establishing facts concerning perceived social phenomena. Qualitative data collection is achieved through subjective and personal procedures entailing observation and interviews, while its analysis entails descriptors to identify and connect patterns and themes. In contrast, quantitative research entails the measuring of phenomena through tools such as surveys to obtain data that can be analysed for comparisons and inferences to establish statistics.

This study employed qualitative research methodology as part of given the evaluation of the causes of expatriates’ failure. Given the data collection methodologies, effective information regarding the life of expatriates with regards to their experiences, family and organization support and training, culture differences as well as adoption to life in a different country was obtained and analysed into different themes. The collected data was core in highlighting the reasons for expatriate failure as well as human resources departments’ efforts and strategies in being able to increase successful rate of expatriation.

Data Collection Methods

Data collection is the essence of research and its reliability and validity determines the success of a study. This section highlights the different methods that were involved in the actual process of collecting data in the field. Based on the mixed methods nature of the study, the research adopted the combined use of questionnaires in highlighting general aspects of expatriates life and cycle within foreign countries, as well as follow up interviews on expatriate respondents to further emphasize on individual opinions and sentiments regarding the actual experience of expatriates lives and how these can be significantly improved by organizations and different human resources available. These different sources and techniques of the primary data collection processes are further described in line with (Brinkmann, 2014).

Questionnaires

According to Phillips and Stawarski (2008), questionnaires are efficient due to their ability to capture not only an individual’s opinion, but also their attitudes and beliefs. In addition, they are flexible and easy to fill up in a short time. The questionnaires used contain detailed questions mostly requiring either a Yes or No answer, and in specific limited instances offer ranking scale and/or choices that respondents can easily pick for their response, plus a few open-ended questions for clarification of deep insight points. The questionnaires were filled online via Survey Monkey that enabled momentary filling and response from American /European expatriates in different countries all across the globe.

Informal Interviews

The researcher further follows up 3 of the questionnaire respondents available within the UK with a short informal interview to be able to find much deeper and personal insights of the respondents’ relation to the topic of study. This is especially important to be able to receive explanations on any grey areas present in the questionnaires as well as ensure credibility and viability of the information provided by the respondents.

Target Population

According to Gobo (2011), Population can be defined as a group of people, subjects, objects and/or items that impact an element of the study being taken up and as such, are of interest to the research process (Goddard &Melville, 2004). These are people with a specific attachment or approximate to the features or subjects of the study that are being researched (Morse&Richards, 2002). Based on the data generated from the use of the literature review, to boost the quality of the research outcome (Crotty, 1998), the research process involves the use of a structured questionnaire and follow up informal interviews to collect information from 15 key expatriates from the UK, Spain, Italy, France and the US. Given the evaluation of the success of expatriates is especially focused on Multinational Companies.

Sampling

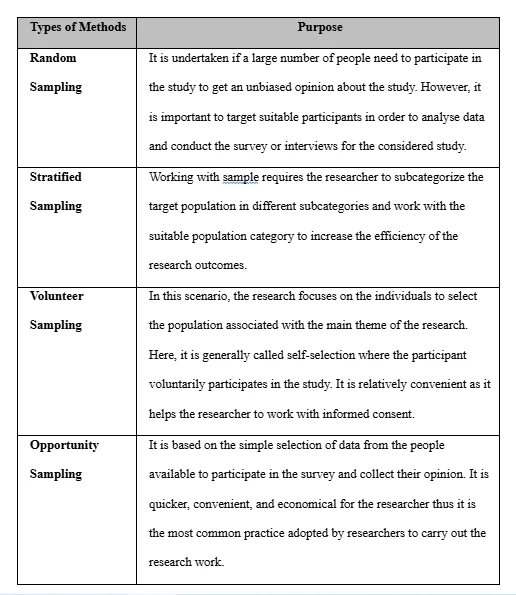

Sampling is the parameter that enables researchers to select a suitable group of individuals or items from the population for data collection and analysis, consequently as such, influencing the overall research results. It is therefore paramount that collection of data is acutely relevant to the key themes of the study, the research design and research strategies. The most basic sampling methods entail either probability or random sampling, which gives equal opportunity for selection to the entire sample population; as opposed to non-probability or non-random sampling, which requires a specific rationale for the inclusion or exclusion of sample groups of a population. The distinction between these sampling methods highlights the research principles that researchers consider prior to selection of appropriate methodologies and data collection techniques (Smith, 2015; Taherdoost, 2016; Tarone, Gass, & Cohen, 2013). Sampling design identifies the nature and quality of the research framework, the availability of secondary information sources to support primary data, accuracy measures, the detailed analysis of content, and operational concerns related to the undertaken research (Reynolds, et al, 2014; Gast & Ledford, 2014).

While quantitative methods typically depend upon probability samples that permit confident generalization from the sample to a larger population, the ideas behind a specific sampling approach vary significantly and reflect the research objectives and questions that direct the study (Palinkas et al. 2015). Knowledge of the range of one’s population and its composition is integral in the determination of whether probability sampling can be implemented (Blaikie, 2010).

Techniques for probability sampling methodology options are set out in Table 1:

This study employed the use of the Opportunity probability sampling technique given the scarcity and inaccessibility of the study population. The researcher used referrals from the key contacts to assemble a group of 15 key informants. The sample was also carefully selected based on their possession of expert knowledge and experience in different relevant areas, such as international business management, global franchising, and international marketing.

Data Analysis

Qualitative research methodology research involves analysing information from a subjective perspective thereby relating different experiences to predetermined outcomes. In this study, the analysis of qualitative data was conducted using thematic analysis.

The results of the structured interviews were transcribed, organized, processed, validated, coded, and analysed to determine the prevalence of important themes, a process called thematic analysis, to help address the research agenda. The interview results, including the predominant themes distilled from the interview responses were triangulated with literature review and case study findings to relate to the research issues, key questions, and objectives.

Justification of Analysis Methodology

In the data analysis of qualitative research studies, researcher uses primary data which is fundamentally disorganized and manifests as singular opinions. It is essential therefore to organize it, break it down, synthesize it, and search for specific patterns that highlights what is important as well as what is to be noted and learned so as to decide how the information is presented in such a way that the reader will understand (Bogdan&Biklen, 1982). Qualitative studies tend to produce large, often unstructured amounts of data, and analysis can sometimes be problematic (Turner, 1983); but they offer the researcher the opportunity to develop an idiographic understanding of participants - and what it means to them, within their social reality, to live with a particular condition or be in a particular situation (Bryman, 1988).

The conceptual framework used in developing the entire research including the objectives, the literature review as well as the structure of questionnaires and interviews builds upon the theoretical positions of Braun and Clarke (2006) who premises thematic analysis as a method used for “identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within the data. The general process will therefore involve a variety of phases including familiarizing with the primary data, generating initial codes, and classifications, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and eventually producing the required report. Accordingly, the emerging themes are assigned a specific code. The codes applied are keywords, which are used to categorise or organize text and are considered an essential part of the qualitative research (Sarantakos, 1998, cited in Schumm, 2016). Subsequently, the researcher identifies reoccurring themes throughout, and highlight any similarities and differences in the data interpreted, eventually, the data is put through a verification process that involved re-checking the transcripts and codes to verify or modify conclusions earlier reached to answer the research questions and objectives.

Ethical Consideration

Involvement of humans as a source of information or the population of study requires the application of moral frameworks and their considerations from the early stages of research (Biggam, 2015; Oliver, 2010) The study should be able to occur whilst respect to human dignity, autonomy, privacy and integrity of the participants is observed at all times. While very little potential risks are envisioned as far as safety and dignity of participants is preserved, the researcher recognises the necessity of the inclusion of key areas of ethical concern including competence, confidentiality, informed consent and conflict of interest, to be considered in the collection and data analysis processes to avoid legal or ethical issues impacting this research findings or further investigation on the topic.

Competence

The goal of this research was to collect and analyse data to increase understanding of the topic and its objectives. The researcher was responsible for maintaining the competencies of all collected data from both primary and secondary sources, and to avoid issues concerning the credibility of the research data (Lather & St. Pierre, 2013).

Confidentiality and Informed Consent

Working with primary data collection necessitates that researchers gain the trust of questionnaire and interview participants, and provide them with a commitment to confidentiality and security of the information provided by participants (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2017; Lather & St. Pierre, 2013).

Conflict of Interest

Consideration of any conflict of interest for either the researcher or participants during the course of the research process, arising from their duties or obligations in the interview and/or the questionnaire processes. Researchers have a responsibility to protect the interests of interviewees by considering potential areas of conflict for participants by bearing in mind their best interests or issues that could potentially lead to biased opinions or responses.

Consideration for all ethical and/or moral values associated with the research is essential to ensure adherence to all professional research standards and approaches of reporting, credits, and plagiarism in order to protect the researcher from present or future ethical or legal issues. Focus on the code of ethical practices ensures the statement of principles and procedures is followed according to the ethical guidelines (Gast & Ledford, 2014; McCusker & Gunaydin, 2015). Adherence to the code of conduct allows researchers to avoid issues by considering issues that might affect the research over any ethical concern (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2017)

Chapter summary

In summation the research will utilize the qualitative research design with the philosophical leanings of interpretivism to evaluate the various factors among expatriates that contribute to their success or failures. Using questionnairs and follow up interviews, the research will collect information from 15 expatrites from the UK to the USA and other European Union countries such as Spain, France and Italy as well as expatriates in the UK from these countries. The information will be collected in acordance to the stipulated ethical considerations and eventually analysed with the use of thematic analysis highlighting different themes and patterns with relation to causes of expatriate failure and strategies that can be taken up by organization and company HR departments in ensuring improved expatriate success.

Chapter 4: Data Presentation, Analysis and Discussion

Introduction

This chapter highlights an analysis of the primary data collected from the study through questionnaires to different expatriates working within the UK and from the UK to other countries within the European Union. Thematic analysis is used in the presentation and analysis of the various responses given by the respondents in the questionnaire and interviews, consequently classifying different data into thematic patterns that are consistent to the Literature review. These are then used in the discussion section to outline inferences in line with the literature.

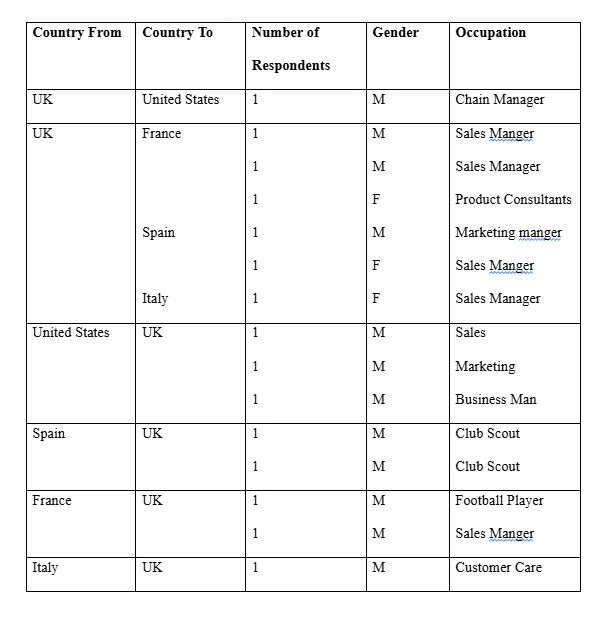

Respondents Background

Among the 15 respondents who made up the sample of study in this research, 12 were male representing a percentage of 80% of the respondents while the remaining three were female respondents. All the respondents had spent a substantial amount of time as expatriates, ranging from 2 to 5 years and were in different occupations ranging from sales and branch managers of different multinational companies with branches in the respective countries. One respondent however was a business man while another one was a professional football player. 6 respondents were British expatriates in other countries within the European Union (EU) including France, Spain and Italy while another respondent was a British expatriate in the US. 3 respondents were American Expatriates to the UK while another 2 couples were from Spain and France to the UK. One other respondent was from Italy to the UK.

Data Findings and Presentation

The research asked the respondents a wide range of questions to evaluate respondents experiences as expatriates as well as collect information regarding expatriate deployment and life such as the training, selection processes, family concerns, stereotypes as well as conflicts all of which are factors that contribute to causes of expatriate failure, as well as subsequent success and which significantly highlight the efforts by the HR departments of various organizations towards ensuring expatriate success. The findings of the different questions were presented under different subtopics including: HR Practices and Support, Culture, Family concerns, stereotypes, conflicts and the general Impact to expatriate life and company.

Human Resource Practice and Support

The research seeks to highlight the kind of HR practices as well as the amount of support offered by corporate sponsor company in the home country of expatriates, meanwhile discover how these factors’ influence to the eventual success of expatriates.

Training

The findings highlight a significant availability of personnel training before deployment to foreign countries as expatriates. Only 10 out of the 15 respondents highlighted having received sufficient training with regards to their duties and responsibilities as well as on matters regarding relationships and adaptation in the foreign countries. It is important to note that 2 of the remaining 5 who had no training from their parent company are in fact the Business man and the Football player who are self-initiative expatriates. All 10 of the respondents who indicated having received training confessed that in a way the training they received prior to leaving their countries was quite helpful to them towards their adaptation and experience in the foreign countries. All the 10 respondents’ also had no problems with regards to work ethics, time planning and decision making due to effective training on the company’s operations even in the foreign economies. Significantly enough however the other 5 respondents cited a variety of problems with regards to adapting into the company’s time plan and decision making processes,which highlights an impact of lack of training to eventual expatriate experience and success.

Selection Criteria

The Human Resource department and the company by extension have a significant role in the success of expatriates particularly through their selection and recruitment criteria for expatriates. Much more considerate selection process may significantly increase the success of expatriates. However to enable an all-inclusive selection process, HR departments should consider a wide range of factors including personal personality, fitness and consent, period of assignment, cultural differences as well as their general adaptability to the foreign country. The findings point out that while all the 15 respondents consented to becoming expatriates and actually feel fit within their respective host countries, 2 out of the 13 assigned expatriates also confessed to anticipating a quick return to their home country and were not particularly certain of their ability to be able to complete their assigned tasks successfully.

While 11 respondents had actually made some friends with the locals in the period of their time, therefore indicating a considerable consideration of social skills in the process of selection, 12 of the respondents including the self-initiativeexpatriate respondents confirmed to enjoying their time in the foreign countries. Further the research highlights that a great deal of companies considered not only the technical skills of their personnel during deployment, but also some of their other personal skills such as social skills. The 10 respondents who received training prior to deployment also highlighted the company’s consideration of their personal traits alongside their social skills and other abilities in addition to their technical skills while considering their deployment.

While this data in itself does not speak significantly of the importance of an all-inclusive selection and recruitment technique for expatriate success, when one considers the fact that the 2 of the 3 respondents who confessed to not actually enjoying their time in the foreign country also hadn’t made any friends with the locals, and are the same ones who were in dire anticipation to return to their home countries, in addition to being among the respondents whose parent companies did not offer any training prior to deployment and considered only the individuals technical skills rather than their personality and other skills, then the importance and significance of personnel selection by the HR department to success of expatriates is clearly highlighted.

Support

In highlighting whether or not the parent company supported expatriates during their deployment, the findings highlights that all the 13 assigned expatriate respondents indeed received different kinds of support from their corporate sponsors including help with accommodation and transportation allowances, helping during meetings with local employees as well as transfers. All the 13 respondents also highlighted that their corporate sponsor companies are often in contact with them for updates and debriefs on the current situation in the ground, as well as highlighting and solving any problems and challenges that the expatriates might be facing at the time. This highlights significant support from parent company and could effectively be one of the best HR practices towards ensuring expatriate success.

Culture

Consideration of the possibility of different cultural practices and association between the host country and the home country of the expatriates is indeed another significant factor for consideration in order to ensure expatriate success. While all the 15 respondents acknowledge that they indeed experienced a significant culture shock in the different countries for where they were expatriates, only up to half of them, 7 respondents out of 15, highlight that cultural difference is indeed the most challenging part of their overseas assignment, another four respondents (significant to note: were 1 expatriates from Spain and 1 from Italy and 2 from France) highlighted language barrier as a significant challenge in their ability to effectively carry out their duties. Also significant to note is that 3 of the 5 respondents who claimed culture to present a challenge were from the 3 companies that did not offer prior training before deployment while another 2 were the self-initiative expatriates. The other two respondents worked in product sales and customer service, departments that involve significant contact with consumers and customers as such culture most definitely plays a significant role in the efficiency with which they work.

The 7 respondents also point out that they indeed experienced a cultural identity change while in their overseas assignment highlighting the need for change in being able to successfully carry out their assigned tasks. 10 respondents further pointed out the necessity of experiencing and undergoing a cultural change to be able to effectively carry out their duties in the foreign country. One of these respondents who highlighted that they did not experience any culture change but acknowledged the necessity of change in being able to be a successful expatriate, highlighted that part of the training he received from their parent company included appreciating multicultural practices and fitting into them without necessarily shifting ones’ ideals and values to match those of the different culture, as such highlighting the importance of cultural factors in expatriate success.

Family

Another major factor that impact expatriate success includes Family and the various issues that revolve around it. 11 out of the 15 respondents highlight that overseas assignment would be much easier with family members around as compared to without family members. This highlights a critical impact of family in the wellbeing and success of expatriates within host countries. 2 of the 4 respondents who thought it would be easier without family are the self-initiative expatriates while the other 2 highlighted lack of an immediate family member they would want around.

Stereotypes and Discrimination

Among the major causes of conflict and challenges that expatriates face include discrimination as well as stereotyping. These factors are mostly exhibited in the process of communication between employees in the course of carrying out their duties and may significantly impact general communication and subsequently impact efficiency with which employees carry out their duties. According to the findings all 15 respondents agreed to having experienced negative stereotypes based on their countries of origin from the local employees, and while these stereotypes were not necessarily aimed towards impacting them some of them might take it differently and suffer psychological consequences.