Impact of Commercialized Athlete Performance

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

Background Studies

Athletes, in contemporary sporting environment, are constantly demanded to have a higher performance. A competitiveness in sport whether as a recreational runners or professional chess player, is characterised by intense demanding endeavour. As pointed by Passos et al. (2016) the rising competitiveness in the industry particularly competitive sports place higher demands on an athlete for a better outcome. For instance, fast-developing online gaming industry requires a player to constantly learn and prepare to compete with others sourced from not just immediate geographical neighbourhood but global stage. Same applies to sporting field that include football, basketball, cricket and baseball. Commercialisation of sports has played a major role in increasing demand for higher outcome. Currently, nearly all sports in any level of participation have sponsorship or some variety of commercial venture. Clubs have shirt deal with major business brands, business have naming rights on major stadium and training facilities, leagues signing broadcasting rights with television companies, players associated with shoes and boots companies, and racing cars sponsored by car manufacturing entities. For professional sports, this business association under sponsorship and ventures is instrument in injecting needed financial support for paying the athletes and acquiring modern training facilities but it comes with negative effects of demand for higher outcome. The commercialisation in sport in grounded on media exposure and public awareness of a sponsoring brand. For instance, Hughes (2020) in the High performance podcast explained a five step theory to change (i) a dream and this then becomes (ii) commitment (iii) then every project hit a “messy middle” which is the tough time where you have gone too far to go back but you cannot see the end in sight. To most it looks and feels like a failure stage but removing the manager could cause a reoccurring perpetual pattern where stage four is never achieved and it becomes impossible for the team to get to the next stage to enable high performance. The seeds of progression stage (iv) where green shoots of success become evident before (v) the arrival stage typified by success and emanates back to the dream stage to build on the success. As you can imagine not having the knowledge of barriers when in stage (iii) could mean that teams result in a cyclical nature where stage (iv) is never engaged (Hughes, 2020).

Due to the competitive nature of a team, its selection and the impact the social brain (Rock,2009) has on the dynamism of a team, staff have to be aware of negative and malignant players identified as by Cope at al. (2010) as cancers and cultural assassins (Cruickshank, and Collins, 2012).Through a potential lack of individual consideration these players can emerge causing uncertainty, formation of cliques and disruption off the field for players and staff which impedes the opportunity for group goals and teamwork by negatively impacting values, beliefs and expectations (Cruickshank and Collins, 2012; Samuel et al., 2011; Cope et al., 2007; Fletcher at al 2006; Billett, 2004). This can create a barrier to players self-identifying with the team which blocks the desired outcome of positive behavioural outputs to group and organization (Chen et al., 2015) Potential barriers to High performing teams can manifest on the sporting arena when the importance of teamwork and cohesion is not respected. In 1992 the ‘dream team’ basketball team showcasing the best talent in the world lost by 8 points to a college basketball team. Talent needs the cohesion and teamwork to have a chance to be high performing. Once the team mastered this the ‘dream team’ won every game at the 1992 Olympics scoring over 100 points in every game (Keller et al., 2017). Talent alone is not enough (Dweck, 2008) and the All Blacks demarcate on selection of players that are talented but threaten the cohesion of the group with their policy of ‘no dickheads’ (Leaders, 2017). High performance Sport (HPS) has emerged as the umbrella terminology encapsulating the external growth, enormity and penetrating nature of elite sport on the global scene in this dynamic environment (Sotiriadou et al, 2018). A sustained high performing team is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon which is coalesced by both internal and contextual factors. Internal factors interrelated to teams’ concomitant with external pressure derived from primarily from potential revenue can have an enervating effect on a high performance team. The global sports market had revenues of $458.8 billion in 2019 with an expected trajectory to give a figure of $826 billion by 2030 (Businessresearchcompany.com), so external pressure will continue, but the literacy research points to success and barriers through psychological and social traits to master high performance.

Heighten competitiveness in elite sports necessitate putting in place structures towards a high performing team. As pointed out by Ronald and Jean-Pierre (2019), increasing commercialisation of sports particularly competitive elite sports has put more pressure from on the clubs and teams for better results. Business entities sponsoring a club or an athlete are concerned primarily with bottom line. The broadcasting business entities focus on the number of viewers switched on to watch the games where shirt sponsors look at the number of merchandise sales. Collectively, the sales whether tickets and merchandise, games attendances, live games watched, and club/team association is largely subject to games performances. Therefore, this raises the question of the enabling factors of a high performing teams.

Research Aim

The aim of this study is to investigate the socio-psychological barriers to high performing teams in sports.

Objectives

The objectives of this research is to:

Critically investigate the social factors that limits a sport team from achieving a high performance

To analysis psychological factors hindering a sporting team from attaining a high performance

To evaluate socio-psychological factors enabling competitiveness in a high performing sport teams

To appraise the primary and secondary data then formulate recommendation on socio-psychological factors influencing sport team to high performance

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

The literature review chapter will consider the extant research conducted focused on potential social and psychological barriers to a high performing team (HPT). It will analyse through a deductive rationale due to much of the literature emphasising positive experiences of a HPT. The researcher delineates where the potential barriers sit within a macro, meso and micro context of the of high performance sporting model in the title of the barriers. Within this chapter, the emphasis is critically analysing literature related to research topic and problem, high performance in sport, but its concept is drawn from the wider social and psychological fields which may not be directly derived from sport. This is done to give more substance to nuances within certain subjects such as teams to help aid the inference related to potential barriers in sporting teams.

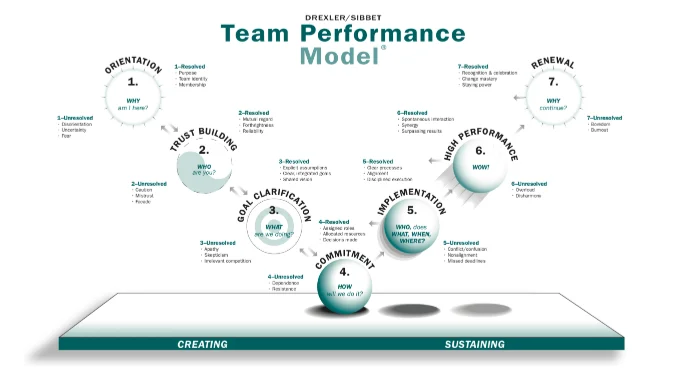

Team Performance Model

Under Drexler/Sibbet team performance model, there are seven concepts underlining solid team development that results in higher performance. These include orientation, trust building, goal clarification, commitment, implementation, high performance, and renewal. Drexler and Sibbet, (2004) argued that each individual team member has to be oriented through made aware and understand the purpose, goals, and team identity for them to develop a shared commonness. This a core in identifying and feeling part of something bigger than oneself. The model highlight trust building under such positive parameters as mutual regard and reliability while also clearly and explicitly outlining the goals. As elaborated by Singh and Gupta (2015), team building requires nurturing commitment among team members as well as to being involved with the goals. The other branch incorporates: the implementation involving developing a roadmap and alignment to attaining satisfactorily the outlined goals; high performance taking into account the spontaneous interaction and surpassing the targets; and lastly, renewal that consists of recognition and celebrating effort and outcome (Drexler and Sibbet, 2004). Going the argument held by Milne (2007) and Helmreich & Schaefer (2018), recognising individual and group input as well as output is a motivating factor incentivising one to put more effort, engagement, and productive. Recognition informs the large metric of engagement, retention, attaching talent, and productivity (Poore et al., 2019). However, this need to embody structured systems enabling transparency and fairness, where team members at acknowledged by both colleagues and management for their contribution.

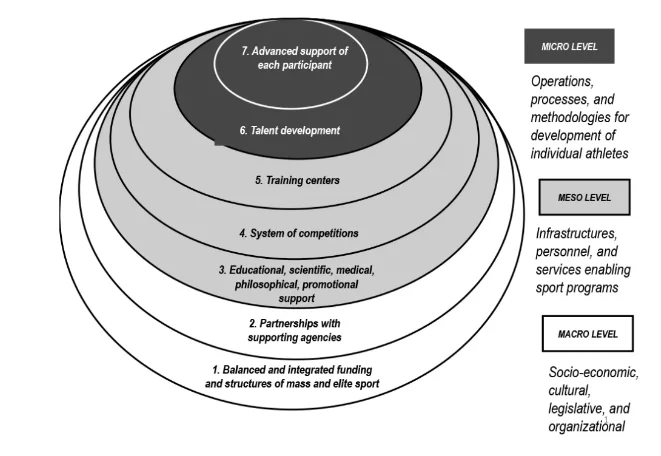

High Performance Management Model

Smith and Smolianov (2008) modelled a framework outlining levels of performance. The ingredients consisting of micro, meso, and macro levels collectively informs the larger performance framework (Figure 2.2). As stated by Smith and Smolianov (2014), success in terms of a team is subject to external factors (macro) and internal factors (micro) of an organisation with such parameters as training centres, system competition, and supporting factors such learning, medical, and promotional elements acting as an interlink between the two worlds.

Long Term and Short Term Planning

The first barrier identified within the research relates to how an organisation view success. In sport solely, short term thinking is a potential barrier to high performing teams. For instance, Sir Alex Ferguson valued short term but not at the detriment to sustained high performing team, with star players he “would have to cut the cord” (Elberse, 2013, pp121) if negatively affecting the long term potential of his squad. Ashley Giles whilst being interviewed by Young (2020) endorsed the salient perspective that long term and short term were both possible, cleverly using an analogy of the Penny Farthing bicycle explaining that the short term of the front wheel is quick and dynamic whilst, in tandem, the back wheel turns slower and delineates the longer term planning and chance of a sustained high performing team. Collective team members’ optimal performance and the challenges of seasonal wins, draws and losses it is important to distinguish between long term and short term success. It is an erroneous assumption to believe that a high performing team (long term) which performs successfully over a sustained period of time are akin to a high performing team that shows no sustainability (Cruickshank et al., 2012).

Organisational Culture in Sports Performance

Empirical evidence has accentuated the importance of culture in high performing sporting teams. Culture is galvanized through identity and a sense of purpose (Sokro, 2012; Maitland et al., 2015; McDougall et al., 2020). For instance, Barcelona FC has a strong historical identity based on the geopolitical subjugation of Catalonia in 1719. This ubiquitous influence of identity, does not need to be derived from historical identity, but in Barcelona’s case it is evident when the Catalonian crowd sing in 17th minute and 19th second or every game (Hughes, 2020). A sense of purpose is incipient in sports cultures. A strong commitment culture can do much to ameliorate potential barriers of high performing teams (Hughes, 2020; Rathwell, and Young, 2015). Empirical research show that high performing cultures such as the commitment culture ignite when a processual dynamism prevails distinguished by a shared value and belief system spanned through the generations within the team (staff and players) where expectations and high level of performance are met (Fletcher et al., 2011, Cruickshank et al., 2013; Feddersen et al., 2020; Saleem et al., 2019). Within this, group culture can significantly shape an athletes psychological level influencing well-being, behaviour and potential development (Anderson, 2011, Duda, 2010). Potential barriers to high performing teams are when these cultures are not strong. Strong cultural ties build on such attributes as fairness, integrity, adoptability to change, employee engagement, having meaning and outlined goals, and teamwork (Odor, 2018; Sergiu, 2015). All teams will have a culture but if it is not a robust, positive or strong culture it is a differentiator between sporting organizations that are propelling themselves towards peak performance associated with sustained high performing teams (Eskiler et al., 2016; Erhardt et al., 2016). Katzenbach (2012) identifies 5 cultural aspects that drive peak performance in teams through business. These are critical shifts in behaviour, openly communicated sharing ethos, aligning culture to strategy, integrating formal and informal interventions and measuring and evaluating performance.

Role of Leadership in Sports Performance

Leadership play a critical role in a high performing teams (Kotter, 2012). Lyubovnikova et al. (2017) states that authentic leadership motivate the actions needed to alter behaviour that include meditating team reflexivity. Leadership, nevertheless plays a fundamental role in employee behaviour and motivation (Gond et al, 2012) and is a pivotal conduit to creating a co-vision permeating and aligning strategy, influencing pace, allocating resources, enhancing engagement, driving accountability and delivering results (Bhalla et al., 2011; Arthur et al., 2017; Cotterill, and Fransen, 2016). There is not unequivocal proof one leadership style is always a key to sustained high performing teams. However, a potential barrier could be articulated in a leader centred style as it hastens to modulate the standards that create and regulate principles of sustained high performance (Cruickshank et al., 2012). On the opposite side of the leadership continuum is servant leadership. This largely altruistic style would be seen as a potential barrier to a high performing sports team due to the capricious nature of high performance sports, and the leaderships style’s dominant focus on sustainable long term performance it would impugn the need for short term performance and is largely based at present in nonsporting fields (Eva et al., 2019; Sendjaya, 2015; Hu et al., 2011; Van Dierendonck et al., 2011). Less of a barrier to high performing teams due to the proliferation of evidence from researchers suggests that transactional style is successfully being evolved into a more transformational style of leadership (Jaiswell et al., 2016; Mills 2016; Callow et al., 2009; Mckenna 1994; Tichy 1986). Transactional has been seen as risk averse and controlling (Aldair 1990). This style underpinned Sir Alex Ferguson’s leadership style but converging transformational behaviours (Callow et al., 2009) enhanced sustained team performance at Manchester United. He exhibited four transitional behaviours via team talks (inspirational motivation), understanding the player’s needs (individualised consideration), involving Sir Bobby Charlton (role modelling) and the being laser focused on high standards. He preferred a coach led and prescriptive coaching style rather than intellectual stimulation through the team taking ownership and a transactional, leader-led goalsetting rather than the transitional method where fostering the acceptance of group goals is the foundations of the transitional style (Elberse 2013; Elberse et al., 2012). Leaderships in sporting industry follows a model of bring individuals with different talents, abilities, level motivation, ambition, socioeconomic background, and beliefs then moulding them into a ground with shared goals and game plans.

Learning and Development Environment

High performance is the constant pursuit of excellence through learning and development (Gleeson, 2019). Among other things, effective leaderships core in bring together and creating conditions for integration and fostering trust among team members. According to Hakanen et al. (2015) and Dyer et al. (2013), fostered environment of trust goes both vertically and horizontally where subordinated are entrusted with role without constant follow-up while management to put the interest of the team first is a recipe of effective team. In sporting environment, for a high performing team, there has to be trust and certain vulnerability otherwise trustees enter the second step of the model the ‘fear of conflict stage’. Positive learning environments are typified at this stage to introduce psychological safety, a critical process of development where interpersonal trust without fear of being reprimanded or marginalised is facilitated to frame mistakes as “cognitive catalysts” for the betterment of stimulation and innovative thinking (Keiser, 2021; Dovey, and Singhota, 2005; Cole, 2012). Conducting pre-performance routines followed by elite Chinese diving team, Yao et al. (2020) noted that the team spectacular failures are applauded in the innovative phase of experiencing and creating new dives. Building from the psych-social safety that empowers open interpersonal communication of unfiltered and passionate debate, listed as one of the traits of an effective team (Shelton et al., 2010; Pescosolido, and Saavedra, 2012), show that a thoughtful disagreement gets you quicker to the truth while showing no threat response to impact social dynamics of the team (Syed, 2019). If this conflict is mismanaged it causes serious damage to individual, dyadic and whole team relationships (Segal et al, 2019). Working together and cooperating the management of conflict can help team mates convince that their team mates are trustworthy. These trusting relationships are increasingly significant to high team performance (Hempel et al., 2009). Rego et al. (2013) points out that a ‘lack of commitment’ raises ambiguity as previously team members have not bought into the process which results in lack of transparency, purpose and ultimately a lack of desire. Launder and Piltz (2013) believes that high performance coaches need to go beyond technical and tactical skills and facilitate an environment where leader- follower and coach athlete relationships evolve through emotional intelligence. In a case study on the All Blacks a great deal of planning, teamwork and execution of performance goals where facilitated through an emotionally intelligent dual management process (O’Connor, 2020; Johnson et al., 2013). A committed leadership team of selected players worked symbiotically with the team and delineate aligned direction and transparency of a mastery climate using a transformational leadership style to gain best results in training and games (Hodge et al., 2014). Under Lencioni (2012) concepts of dysfunctional team, the ‘avoidance of accountability stage’ depicts a lack of cohesion and behaviours counterproductive to performance. This stage is unfamiliar with high performing teams such as the All Blacks who believe champions do extra to take them beyond good to great ensuring everyday activities show personal humility such as ‘sweeping the sheds’ (Hastings, and Pennington, 2019; Hodge et al., 2014; Bull, 2018). According to Lencioni (2012), the ‘Inattention to results’ where players and staff are not aligned leads to lacking motivation and prioritise energies selfishly ego centric in nature on their own careers. Based on this, one would argue that All Blacks who collectively modelled for a better and positive results through development of a highly competitive culture would dismiss ego to concentrate their shared goal to leaving the jersey in a better place (Kuroda et al., 2017). Coyle (2018) modelled that success of a team is brewed on looks carefully at the psychological and learning potential of an individual member. Examining the effect of targeted learning on the performance in football sports, Franck and NŸesch (2009) highlighted that effort needs to understand that when facilitating the learning and development of human beings. This tend to have huge implications on environment as well as performance. Rock (2009) explains that the coach or team has “the ability to intentionally address the social brain in the service of optimal performance” by understanding and acting on three core aspects of potential development. Firstly, exclusion is instantly connected to the same part of the brain as physical pain (dorsal portion of the anterior cingulate cortex) and rejection from a shared vision or the team in unjust circumstances has a detrimental effect on commitment and engagement. Secondly, psychologically, people tend to shuts down when there is threat to a much slower level to focus on the threat which hinders performance. Lastly reward responses can improve performance. In Rock’s SCARF model the acronym represents collective stages that positively affect performance. Openly competing comparatively with someone else in the team enhances a lack of status. However, uncertainty causes confusion and ambiguity impacting negatively on performance (Certainty). Not allowing the team to execute their own decisions causes stress (Autonomy). Coyle (2009) tells us that primal cues of belonging and inclusion works the unconscious brain which can process 11 million pieces of information per second compared to the conscious brain that can only manage 40 per second (Relatedness). A strong response in the limbic system highlights hostility and erodes trust if an act is seen as not being fair (Fairness).

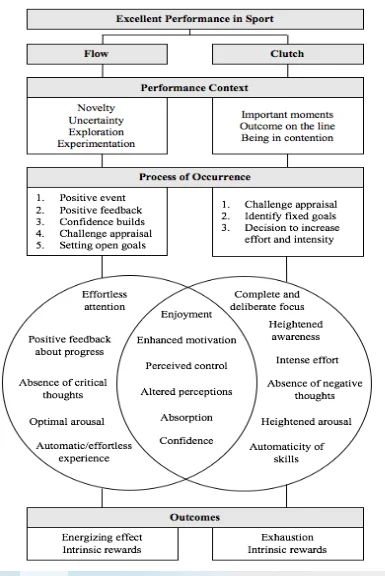

Motivational challenge and engagement is interwoven in the fabric of optimal performance, disconnecting or understating this would inhibit a high performing team. The Flow model of Csikszentmihlyi engages a more subconscious state of the brain the possible sweet spot of intersection of skill ability of the player with the correct level of challenge complexity in the task if applied proportionally (Swann et al., 2017; Nakamura, and Csikszentmihalyi, 2014; Swann et al., 2012). Gauging the skill level of the group/player to the challenge is key for engagement. If the skill level is high and the challenge low the result at the extreme level is boredom and when the challenge complexity is too high and the skill level is low the result at the extreme level is anxiety both extremes hinder optimal performance (Thompson, and Nesci, 2016). Relatively studies by Swan et al. (2012) and Swann et al. (2012) suggests that there is an addition to the psychology of optimal performance which can work synergistically with flow towards goals related to optimal performance. This ‘clutch’ state manifests “under pressure circumstances” (Otten, 2009, p. 584) when an athlete is consciously aware of the competition, perceives the outcome as important and deals with the pressure whilst performing the skill with emphasis on effort (Hibbs, 2010). Therefore, based on this, one can argue that the environment specifically the learning and developing of players and staff is an essential element towards betterment of team outcome. Literature regarding trust in sports teams has not comprehensively exhibited dynamic granular influences on the interplay of teams and individuals related to sporting scenarios. However, based on the concepts outlined by Lencioni (2002) on dysfunctions of a team and used sporting, several parameters affect team performance.

Teamwork and Cohesion on Sport Team Performance

Cohesion has historically been considered one of the most integral variables in the study of team dynamics (Pescosolido et al., 2012). Callow et al (2009) whilst working on their Differentiated Transformational Leadership Inventory (DTL1) found that three out of the six leadership traits positively predicted team cohesion. These were fostering acceptance of group goals and teamwork, Individual consideration of team members and high performance expectations from the leader. Sullivan and Feltz (2003) thought that the first two socio-emotional traits predicted a greater acceptance of positive conflict resolution as well as less negative conflict management to enable greater team cohesion. Highly cohesive and unified teams will work together more effectively and therefore perform better than less cohesive teams (Smith et al, 2013). There is a significant trend in human creativity shifting from individuals to teams with collective intelligence and skillsets being unified to undertake the most challenging work (Syed, 2019) but there is a social element to performance and cohesion in the unification of collective performance, as the team have to learn about each other and this amplifies functional and positive performance but can also cause dysfunctional teams (Pescosolido et al 2012). Measuring the correlation between team cohesion and performance level, Callow et al. (2009) basing on the confirmatory factor analysis revealed that leadership behaviour towards fostering acceptance in a group includes individual identity, goals, and views is significant in promoting team work and performance expectations. Mach et al. (2010) on differential effect on team performance highlighted dynamicity among teams, fostering trust, coordination, and cohesion among the members as a critical step toward a shared consensus. The interdependence among the team members creating mutual dependency creates cooperation and interaction. Therefore, it is plausible to suggest that if there is a lack of knowledge regarding values and the behavioural impacts on teamwork and cohesion, the sporting club would have to deal with the corollary of these barriers.

Performance Management Design Within a Club Structure

The core being based on the performance management structure throughout a club being integral and focusing on the why as a good initial point to eliminate ambiguity and inject a passion to drive a project and vision (Sinek, 2009). Starting with a shared vision articulates the why, as it implies a greater possibility that team members implement innovations and workflows aligned with the vision (Hulsheger et al, 2009). Design is required to give accountability across the whole sporting landscape, removing ambiguity and prioritising quicker, more focused decisions with improved performance potential and greater engagement (Bhalla, 2011). Staffing should have clear roles and responsibilities to posit team outcome and performance. Performance management design needs to match the sports club’s business model and ethos (Potroc and Jones, 2009). As an example will a hierarchical structure in the sporting clubs design allow the patience to implement servant leadership culture that may take years when the performance indicators for success is driven by the score line on a weekly basis (Eva et al., 2019). According to Shibli et al. (2013), the management should use their expertise in applying a structure that can evaluate and reward performance progression. However, within the design, the performance management team should be constantly challenging the sporting and business side of the club to align in departmental and inter-departmental challenges through supporting and improving core capabilities (Leinwand, 2017). This may include rewarding teams instead of individuals and a regular review of the teamwork itself, as well as the team goals (Wheelan 2013) or it could be a design of long term success across all the football and business side of the club to identify and developing future leaders (Bhalla et al 2011). In the U.S, sport have been moving more towards high performance sports management (Sotiriadou, and De Bosscher, 2013) with the performance departments augmenting through agility, data and sophistication (Buckingham, and Goodall, 2015; Henriksen et al., 2020). A study by Denison et al. (2020), highlight that high performance practices is subject empowerment, athlete-centring, and autonomous support collectively modelled to promote athlete unique qualities and developmental difference at individual level as well as collectively as a team. These, as argued by Mills and Denison (2013), brew a holistic and considerate coaching approach that puts athlete as core to coaching practices. Rosh et al. (2012) and Methot & LePine (2016) on concept of athlete comfort, argued on distinguishing team intimacy and team cohesion where moderation has to be observed with intimacy to avoid distortion of ultimate team goals, latter bases the components of social and task relations, perceived unity, and emotions acting as building blocks of participating and staying with the group. The process is a strategic approach to plan, set goals and drive staff and players in the same direction under an integrated high performance banner. However, this only focuses on sports science and coaching side in terms of scientific and athletic performance of high performance (Alder, 2015 and Sotiriado and Shilbury, 2013). In high performance teams there is a need for a collective response, not just the scientific and athletic element to an aligned performance connecting to club wide strategic goals (Aguinis, 2009). Building from these, ignoring the social, emotional and psychological element of performance is a potential barrier to high performing teams. One of the high performing teams’ greatest assets are the people in these teams (Hakanen et al., 2015; Claudino et al., 2019) and performance management can bridge this lacuna with a robust design in recruiting, retaining, training, developing, rewarded and appraising within a unified and coherent club wide approach (Armstrong and Taylor, 2014).

Readiness to Innovation and Change on Team Sport Performance

Most team sports have change thrust upon them. Teams change through recruitment, injury, game approach, team ideology, and retirement, which in turn influence tactical styles and training. Uncontrollable external changes become evident for instance funding losses through Covid-19 (Drewes et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2020; Garcia-Garcia et al., 2020) or diminishing relationships with external agencies, such as the media and business sponsor. So timing of when to introduce and apply a bit more challenge and risk taking through something like a psychological safety environment as an example is not easy but the benefits can outweigh the risk if it is successful (Cruickshank, and Collins, 2012; Pol et al., 2020). Kotter (2012) in his “Accelerate” journal brought a possible where organisations utilised the same operations system and created a parallel system beside it to assess, implementing strategy in a timely fashion demonstrating agility and speed to work in the VUCA world (Fenton, and Timperley, 2019) to gain competitive advantage as an agile entity (Bhalla, 2011). However, making that leap to execute a new idea to create value is challenging (Bonetto et al., 2021), particularly if one is conservative, risk averse, or due to past success. These might lead to believing in the teams’ abilities or coaching staff ideologies without pragmatic perspective of changing surrounding. Hence, as illustrated by Dweck (2008), subconsciously not conforming to change to potentially grow and develop. This can develop into a change resistance within the team and there are no easy solutions to overcome this (Breitkopf, 2019). In sports, taking calculated and informed risks is core to better outcome. Sir Alex Ferguson’s incipient nature emphasised that he would never stop adapting. Changing the training regime to a new position specific format which was innovative in its time of 1986, he brought the youth in close proximity to train next to the first team, invested in youth when at the time experienced players (Whittingham, 2021). A study conducted by Cruickshank and Collins (2012) on culture change in elite sport performance acknowledges the interrelationship between teams’ performance and psychological state. The cultural parameters that informs athlete development, forces behind team diversity, ideals of teams’ goals and objectives, and beliefs grounding team’s cohesion are integral in developing a sense of belonging as well as a shared commonness (Maitland et al., 2015). However, optimising culture particularly for elite teams demands a need for informed and evidence-based guidelines to culture change. Cruickshank et al. (2014) identified director-led culture change has having a significant influence on the overall performance due to initiated evaluation, planning, and impact on short and long-term ideals of a team. For instance, both the team motivation and market structure are subject to sport club structures and ingrained concepts.

Chapter Summary

The literature analysed in this chapter appertains to the understanding of social and psychological potential barriers to high performing sports teams. Within this research the inference from the analysis of successful high performing sports teams and the analysis of the slender information on actual barriers, several barriers have been noted. Within these barriers it seems evident that the social and psychological barriers are congruent with the internal and external parameters of an organisation. The next stage of this research project will aim to move this along further by explaining the diligence and process of the research project as a whole in the next chapter. This vehicle enables delving deeper on the content knowledge and help bring together the robust process to push the research further.

CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY

Introduction

This methodology section covers the procedures and process in which the answers to the research question while also achieving research objectives in a systematic manner. The section is subdivided in several subsections with each covering concepts leading a procedural framework of collecting and analysing data.

Research Philosophical Framework

Hughes and Sharrock (2016) argued that a research is built on a number of assumptions that are used as abstract ideas and beliefs informing type and procedure of data collection as well as interpretation. From a social research perspective, the solution to the research problem is built on assumptions that defines views and perspectives held by the researcher. Research philosophy upholds the beliefs inform such assumptions held on the problems and subsequent objectives. Paradigm defines the nature of the world, the researcher’s place in it, and possible relationships one holds with it. This can either take ontological or epistemological paradigms. While ontology deals with reality under subset of nature of being, epistemology on the other hand points to the creation of knowledge focusing on ways in which it was obtained and its validity (Sarantakos, 2012). As pointed out by Bryman (2016), in knowledge creation, objectivism or constructivism paradigms ca be taken. Objectivists argue that reality exists as an independent variable to the researcher’s views. Whereas, interpretivist illustrate that subject in a social setting holds individual and independent perspectives on common interactions. As such, building by the assertion held by McChesney and Aldridge (2019) it takes into account the individualistic experiences and perspectives informed by values and cultural positions in the search of answer to the research questions. As aforementioned, this study focuses on investigative the socio-psychological barriers inn sports industry. Therefore, the assumptions held is that interpretation on the shared social events by acts within the industry would vary. A way in which the experience is interpreted suggest that within the research phenomenology will play a part as the research subjects hold not a clear and measurable objectivity that is separated from their experience and opinions (Merriam, and Grenier, 2019). There could also be symbolic interactionism (Merriam et al., 2016) as the symbolic nature of what is believed is a barrier based on the interactions that can explain the fundamentals of human behaviour in team situations. As the barriers of high performance are social and psychological, it was expected there to be discussions on team environment and culture of the sporting clubs which may touch on the ethnography type of qualitative research, however due to time constraints and through COVID-19 restrictions, competitive environments with the researcher being a potential competitor the immersion of onsite data collection for a long length of time using observation as a primary method of analysis is not possible. (Merriam et al. 2016,). As such, the research philosophy is based on interpretive research, commonly found in qualitative research “assumes that reality is socially constructed; that is, there is no single observable reality” (p9, Merriam et al, 2016) and are formed through subjectivity of views and variables and form a social constructivism view (Creswell, 2011).

Research Approach and Design

Bell et al. (2018) highlighted that a research can take a qualitative, quantitative, or a mixed method. A quantitative research follows expressing the data collection and analysis numerically and statistically. Its importance lies in the use of quantifying a problem then drawing patterns and correlation between the problem at hand and the findings. On the other hand, qualitative research method that captures an insight of a problem through collecting and analysing non-numerical data. The key factor in using the approach is in attempt to understand concepts by going the surface meaning but capturing the experiences and opinions of social actors (Silverman, 2020). In this case, the socio-psychological elements affecting performance in sports demands delving deeper into the concepts and individual participant opinions and experiences. The argument in that influence of the such factors as social norms cannot be expressed statistically rather need an insight perspective. Qualitative study can be emergent and flexible (Merriam et al, 2016). The design of the literacy review led the researcher more towards social and psychological barriers than technical and tactical challenges which then changes the focus to concentrate on these aspects of barriers and has an impact on the overall performance of athlete. Qualitative data consists of “direct quotations from people about their experiences, opinions, feelings and knowledge” from interview situations (Patton, 2015, p14). However, as pointed out by Fossey et al. (2002), the challenge with the approach is running a risk of sample and data biasness. Here, the researcher must be able to refrain from taking personal perspective. This process is called the “epoche” where the everyday understandings, prior knowledge and judgements are put to one side (Merriam et al., 2016) – there can be no prejudices, opinions or assumptions from the researcher. A process of horizontalization is used where the data is observed from different angles to and be given the same weighting at the initial data analysis stage. Then in the process of explicating this data the researcher will then link themes and discussion points that cross pollinate in the interviews. (Merriam, 2016).

Data collection

Data collection Process

In data collection, primary source is used. It is grounded on engaging directly with the researcher participants. Unlike questionnaire that is convenient in collection large data with a short timeframe while at the same time reaching a larger population sample, interviews enables a researcher to delve deeper into the research problem. However, the interviews in this particular research needs to imbue access to the respondent’s perspectives and understandings to the world through the chosen topic. Hence, a structured interview was not relevant as it would not allow this and these type of interviews assume that all have the same vocabulary alignments and this is not always a commonality that can be relied upon by all respondents (Merriam et al. 2016). A semi- structured interview based was chosen on the principals of gaining some specific information with a more structured sense and then there is a part that the researcher guided to get their view from their world and hopefully new barriers that have not been made evident in the literature (Englander, 2012). Roulston (2010) argued that interviews follow a researchers’ line of thinking. In neo-positivist interview, it upholds that a skilful interviewer who asks good questions. It also minimises bias due to the interviewers’ neutral stance and delivers quality data which produce valid findings. While constructionists interview how the data is constructed receives attention through such tools as discourse analysis that differ in meanings to different phrases), narrative analysis that extracting information from stories, and conversation analysis. From the participants’ perspective, holding different views and opinions is a desired value but for interviewer need to be impartial. As such, a neo-positivist interview was taken. Due to the nature of the research focusing on high performing teams, it is not appreciated to observe competitors, particularly if it’s in the same league competition and to keep it standardised across all the sports the interview as the primary mode of data collection is necessary when it’s not possible to observe (Merriam et al. 2016).

Data collection Procedure

Qualitative research through various information communications technologies (ICT). The COVID-19 restrictions imposed by most government globally, forced the interviewing the participants to be done via on-line platforms (Zoom and Google Meet). Although the rapport building is not as good as it is face to face it is much better than in text only or phone interviews (Lobe, 2020). The advantage of zoom is that it transcribes the conversation which ensures everything that is said is preserved for analysis purposes. These have to be checked, but when they are these can be sent to the interviewee to gain clarity that it is what was said and they are happy with the transcribing accuracy but it can be also used as a reflective tool to evaluate how the interview went and if there were times where questioning, exploration through probing could have been used. There is a possibility that it could be quite obtrusive as zoom is a video technology rather than an audio that can be transcribed and may be seen slightly less obtrusive (Archibald et al., 2019).

Preparing the questions:

The questions are at the heart of interviewing and to collect insightful data the researcher must ask good questions (Merriam et al. 2016). A thorough review of questioning was done to see if they include poor types of questions such as closed yes-no, leading questions that can reveal a bias or an assumption from the interviewer or multiple questions. Then pilot interviews are crucial for your pre preparation of interviews as they are a platform to test out questionings to see if they yield less informative data, they are confusing to the interviewee based on words or phrases used and it is a time to practise techniques of interviewing and getting some feedback (Glegg, 2019; Voutsina, 2018). Patton (2015) suggested that ‘why’ structured questions are not too effective as they can lead to speculation and his six types of questions are based around experience and behaviour questions, feeling questions, opinion and values questioning, knowledge questioning, sensory questioning and background/ demographic questioning. Skilled interviews can bring positive interactions by being respectful, non-judgemental and non- threatening (Merriam et al. 2016) as the starting point. Both part can bring biases, attitudes, predispositions and physical characteristics that may affect the interaction and the data elicited. With three variables in the interview Dexter (1970) i) personality and skill of the interviewee ii) attitude and orientation of the interviewee and iii) the definition of both (and significant others) of the situation. Within interviews probing / follow up questioning /exploration can be useful to gain clarity, more information from an interviewee (Seidman 2013). As such, the questions were formulated to be clear and lack ambiguity, try to use participants’ language and not fill the question with jargon

Population sampling

The focus of this study was a high performing competitive sport. A narrowed population target was taken to be interviewed in the elite sports industry. In sample size, Patton (2015) suggests that if the researcher is able to get an expected reasonable coverage of the phenomenon based on the purpose of the study then this number to get this outcome is fine. Because of the time and restrictions, eight participants was taken as appropriate sampled size sourced within elite sporting industry. Acknowledging the wide size of the industry offers in terms of potential population, a probabilistic approach of sampling was adopted. Two basic types of sampling are probability and nonprobability. With nonprobability sampling being the method of choice for the most qualitative research as it solves qualitative problems of the discovery, implications and relationships linking occurrences (Onwuegbuzie, and Leech, 2007). The sampling strategy is nonprobability, with the sampling being purposeful sampling. This is based upon the researcher wanting to gain as much understanding to gain valuable and necessary evidence through the inquisitive lens of discovery and need of understanding (Patton 2015) where the interviewee is called in “precisely because of their special experience and competence” (Chein, 1981, p440) and these information rich cases (Patton, 2015) is central to the relevant enquiry. The purposive sampling allowed the researcher to capture the average person, situation or instance of the phenomenon or “maximum variation sampling” when ‘grounded’ in wide varying instances of the phenomenon and the researcher would select these subjects based on them having core experiences of the phenomenon. Fundamentally, the approach was driven by the need to achieve a calibre and experience that of the maximum variation sampling to get variances in the content of the barriers and with the hope that new barriers are highlighted.

Data Analysis

The main aim of data analysis is to make sense of the data which will mean that gathered data needs to be transformed to useful information. It is a recursive and dynamic process where the researcher collates and consolidates information by reducing and interpreting what the interviewer has given to get into an order that brings you closer to themes (potential answers) of the research question (Merriam et al. 2016; Belotto, 2018). As the researcher takes the first interview the data need to be commented on as one is able to reflect opportunities where it has been explored to get better data through the next interviews and also this sets the start of the next interview as you may add/ take points/ questions away that did not deliver much in the interview. Data also has to be managed to be effective as it is large and complex. So it is important to develop a system to organize the data. Elliott (2018) explained the necessity to code the data so it’s easily retrievable and it is integral to the analysis and the write up of the findings. The coding is the selected notes to identify the comment from the interviewee. The meaningful segments of data from the interviews (units) can then be constructed into a category (theme) enabling to make comparisons much easier when relating to a particular theme of the research where patterns of recurring regularities are evident from multiple interviews that are coded appropriately (Linneberg, and Korsgaard, 2019). Cresswell (2013) further argued that narrowing to fewer categories was easier with a greater level of extraction possible. These categories hold patterns where “you must rely first on your own sense making, understandings, intelligence, experience and judgement” (Patton, 2015, p572). It is at this point that the intensive analysis process can be completed.

Validity and Reliability

“All research is concerned with producing valid and reliable knowledge in an ethical manner” (Merriam et al., 2016 p. 237). It is about providing information and rationale for the study’s processes and adequate evidence for the reader to conclude that the research is trustworthy (Merriam et al. 2016). Lincoln et al. (2011) believed that there are two forms of rigour: one is that is the methodology and the other based upon the interpretations related to judging the outcomes. Lichtman (2013) believes that its personal criteria for a good piece of qualitative research and showing clarity of the researchers’ relationship with the subject (s) in the study. Wolcott (1994) dismisses many thoughts and talks about the “absurdity of validity” (p364) with the key reason to research being the understanding and not a journey for a version of the truth. Internal validity or credibility relates to the congruency of findings with reality. As a qualitative research piece as human beings we are the primary instrument of data collection and analysis- the interpretations of reality are directly through interviews (Rose, and Johnson, 2020). These are only constructions of their realities so an objective ‘truth’ cannot be guaranteed. Triangulation can be used to help make the internal validity and reliability more robust. This can be done through multiple methods of data collection that is observation, literature and interviews), through multiple sources of data such as interviews taken at different people with different perspectives or multiple investigators in the research. In this research triangulation is through a multiple sources of interviewee. Merriam et al. (2016) view that in terms of reliability it is problematic in the qualitative research as there is no benchmark for the study to be repeated and yield the same results. This is echoed in Wolcott (2005) stating that “we cannot make them happen twice. And if something does happen more than once, we never for a minute insist that the repetition be exact” (p159) and questions whether reliability should be addressed at all. Due to people having numerous interpretations of the same data, the integral question is whether results are consistent and reliable with the data collected and would therefore be classed as dependable (Merriam et al. 2016). Patton (2015) states that the credibility of the researcher along with rigorous methods essential to the credibility of the research.

Ethic Consideration

Rigor symbiotic to rigorous thinking inclusive in the investigator, methods and analysis of the research. This integrity is essential that academic fraternity trust the work that researcher has done through an ethical stance (Merriam et al. 2016). The protection from subjects from harm, informed consent, issues of deception all are considerations ahead of time (Merriam et al. 2016). Yet within the research a relationship ethic needs to be exhibited by the researcher. It is the responsibility of the interviewer to treat participants “as whole people rather than just subjects” (Tracy 2013, p245) where there is a sensitivity and value driven behaviour as unknowingly a question may bring up something in the subjects past that may have to be dealt with in a sensitive nature. This is echoed by Stake (2005) illustrating that respondents may feel their privacy invaded with a line of questioning and it could have a potential long term effect if painful memories are brought back to the surface. Therefore, in line with these privacy and confidentiality values, this study ensured all the potential participants signed an informed consent letter descripting the scope, purpose, duration, handling, and storage of the data and information gathered. The letter also ensures that all respondents were aware of their rights to withdraw at any point in data collection without having to explain or give a reason. On the integrity and rigour part, all the sources of the data and information used within this study are cited accordingly and correctly referenced.

CHAPTER FOUR: FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Introduction

This findings and discussion chapter outlines the interpreted data transformed from collected data into useful information. The discussion part involves correlating the findings of this research with previously done research and theoretical concepts. The chapter is structured to capture the analysed data and subsequently the discussion in relation with literature. This research into socio-psychological barriers hindering high performance in sports teams employed a semi-structured interview as primary data collection technique in gathering data to address the research objectives and solve research problem. Data sources were individuals with deep knowledge and understanding on the sporting teams who are working or worked in senior positions of major teams (high performing sports teams). Participants sampled purposively enabled selection of individuals with insight knowledge and understanding of high performing teams include attribute, dynamics, composition, and cultural aspects. Population target was individuals working in teams considered as high performing measured on the league standing, game outcome, and expectations. From sampling, five participants working as directors, coaches, and managers in leading clubs and teams in major leagues. In order to answer the question on what makes and constitute a team to be high performing and posting better results in competitive games, a qualitative approach was followed and then thematic analytic tool used in analysing the gathered data. Before interpretation and analysis process, the data was coded into themes characterised by participants’ perceptions and experiences towards a research question and problem in general.

Findings

Participants Demographics

Five participants were interviewed. Under privacy and ethical consideration onset, the participants’ names and their current teams are withheld. However, each participant is given a code name such as Participant A, B, C, D & E. Moreover, within this report, any identifiers that would in any way identify the participants is withheld. The participants’ demographics include a director of rugby team in New Zealand Super League, a coach of a football league in English Premier League, a manager in Scotland football team, a team manager in a Brazilian football league (Campeonato Brasileiro Série A), and Portuguese football league (The Primeira Liga). The finding is coded in themes discussed below. Building from assertion by Participant B, a high performing teams does not necessarily mean those that win games, trophies or leagues but rather those that exceed expectation, “… any any team that is probably greater than the sum of its parts…” Therefore, within the context of this research, high performing team encompasses a sport team that work together for a common goal and functioning purposively towards establishing an effective operating system.

Team Culture: Cohesion and Togetherness

For a team to be considered a high performer, the players have to be in synch with each other as well as understanding coaching staff and supporting members. In a high performing environment, a team identifies with certain values and ideal that drive psychological aspects as well as the structural and strategical components of a tactics and strategies. In a research on developing a wining sport team culture, Cole and Martin (2018) pointed out that team culture follows integrating artefacts, values, and beliefs that allows players and ideals to flourish. Culture in a team defines ways in which team members including players, coaching staff, directors, and supporting members think, feel, behave, and performed in an environment they practice and compete (McDougall et al., 2020). Participants B and E stated that in high performing teams, culture is ingrained in the beliefs and values including norms and traditional held within both a team and club. Participant B stating “… they have their own culture for that each person in the great the club … they have their own culture for that each person in the great the club, …” It forms core element of team and by extension club identity. Participant E further indicating that, “…because the player understand you don't have escapes, you need to be inside...” However, team’s culture modelled around several founding factors. According to Yukelson (1997), a unity purpose and having a shared purpose bring a ground of players together. Participant argued that a team has to foster a culture of togetherness bring together players, coaching and supporting staff, and managers. Stating, “… bring together a group of players, or staff, …there's it click and understanding and collaboration … enables them to outperform probably the level of each individual”. In a high performing team, there a huge cohort of individuals from different backgrounds, personalities, talent, and age groups “…bring in a team together from four different nations, and how do you do it as quickly and as harmoniously as possible, and so, every time we go on a tour, … it's kind of like, let's not reinvent the wheel, let's learn from four years ago. …”. Participant D illustrated that although some teams composes of players with diverse backgrounds, a team need to develop a shared culture uniting the players together. Appelbaum and Erickson (2018) indicated that an elite sport team is built on ingrained vision on quality, winning games and league (trophies), continuous improvement, competitiveness or attaining short- and long-term goals. According to Participant B, a vision is derived from the top leaders (owners, board and director) trickling down to coaching staff, players and supporting staff include kitchen, medical, kit, and analysis staff. Participant stating, “…vision normally comes from top down again, …I mean top down as in owners and boards, … the board of the custodians of the football club …, whoever you're working for…” The owners and board have to set the right vision for instance, where the club ought to be in the next 6 months, 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years. Participant C illustrated that such questions as ‘That is how can everybody contributes? So how can our under nine coach help? Yeah, how can the ladies and the guys in the in the players canteen? How can the cleaners help? How can you as head of recruitment help? How can you know, everybody?’ set the vision and sight on the larger picture and bring together and including contribution of everybody. Importantly, there must be a connection between the board and formulated vision where they must believe in, practical, measureable, and within available resources. According to Participants A and B, team harmony as well as player connections plays an integral part in overall synchronisation towards shared goals. According to Participant B, a system that is tailored towards achieving higher outcome both in infield and off-field is purposed to be a higher performing team, noting that “…because obviously a high performer culture and teams could be teams of teams or staff, it could be in any industry…”. However, key stakeholders including the players and coaching staff have a shared commonness and vision. The participant noted that, “…. you've got a system, a culture, a coach, probably all of those that bring together a group of players, or staff ...” Moreover, Participant A argued that synergy in a team goes beyond infield coordination but influenced significantly by player-player and player-coaching and other supporting staff relationship. Stating, “…is that most important thing was getting things right off the field not rather than on the field and trying to create a so we're guys is felt like they had an opportunity, there was some harmony within the squad…”. According to Participant B, the vision need to be achievable and relatable to the structure and composition of a team, arguing that, “…every bit of the vision that they set and the parameters within obviously, … not unlimited finance or can't do it tomorrow, but also don't want to do it in 20 years-time, it's got to be achievable and measurable…” In addition to creating an environment where all the players feel comfortable not just with other players but around the coaching staff, according to Middleton et al. (2020), a culture grounded on rituals, norms, and traditions where players understand and share common ideals is core to meeting expectations.

Communication and Coordination

An elite team bringing together players and supporting staff from diverse background is driven particularly by understanding of actions of other team members. Core to this is organisation and coordination linking various nodes of a team structure (Eccles, 2010). According to Participant E, different sections including departmental components need to coordinate and work together passing information and strategies for instance the medical status of a player from medical department – stating “…lots of communication with the medical department and also with fitness. To try to understand, them and to push them to pass with the right information…”. Participant B explained that connection goes beyond player-player and player-coach rather incorporate the vision and goals held by the board and owners, stating “…the connection between the board and the vision”. Based on the findings by Erickson (2020), success of envisaged performance and set goals lies in passing it down and being understood by every involved individual in a team. Participant C emphasized on communication with the player as well as other coaching staff and supporting members to get and understand personal aspects, challenges one is going through, and views held. Eccles and Tran (2012) illustrated that communication in sports involving passing games plans, roles and responsibilities to players and coaching staff in a manner it enhances combined actions is an effective way of team functioning. Findings by Ekstrand et al. (2019) indicate correlation between communication quality between coaching personnel and medical team with players’ injury rates, match availability, fitness and training attendance. According to Participant D, a leader need to communicate effectively with the players passing the intended message and information across as well as buy into an idea and values of a team, Stating “…to make the point across to make your point across…”. However, due to nature of the elite sport teams, effective communication is usually a big challenge. Complexity emanating from cultural, nationality, language barriers, and personality makes it difficult for effective communication between a coach and player as well as supporting staff. A multidisciplinary approach employing various strategies and technique to communicate strategies and develop ideal with a team.

Team work: Collaboration and empowerment

Coordination, according the participants, entails involving all the involved individuals including players, coaching fraternity, and supporting staff in attainment of outlined goals. Engaging the players, as illustrated by Haugaasen et al. (2014), amounts to interacting and taking into account individual and group points of view and beliefs in strategy formulation and implementation. Participant A pointed out that engaging all stakeholders such as group leaders, coaching personnel, and players at individual levels enables brainstorming of ideas and strategies and ultimately making all part of the taken approach. Participant A stating, “…I've done a few things with leadership groups in the past. And I found it fascinating where I picked the leadership group. … we brainstorm and we're talking about what are the character characteristics and make a great player and they'd be talking about it in a disciplined hard work, never gives up ...” Similarly, Participant D argued that engagement and involvement take ownership of the decision made and tactics adopted. Participant B explained that “…if you want people to come on the journey with you, or believe in the journey, or believe that they can contribute to the journey, I think you have to give them some ownership and some empowerment”. In addition to making stakeholders have a clear understanding of team process, engagement allows diversifying ideas and solutions to the faced problems. Participant B noted that collaboration makes players feel being part of something greater than personal satisfaction and meeting basic needs, stating “…getting everybody to feel that had an input into it meant that they it was a bit more powerful…” Participant B further indicated that a leader need to empower the followers through valuing their opinions and views. However, engagement need to be measured such that every team member is brought in and be part of the interaction. Importantly, according to Participant B, a leader need to understand personalities and beliefs of each member and have a personalized way of approach (a strategy that resonate with individual values and beliefs) and engaging with them, stating, “…value your opinions and say, what do you think of this one? And you put them into that situation, although you do have to know your audience a little bit. Some people really don't like…speaking. other little things to do is maybe send some pre reading rounds. I think that gives people especially in certain meetings, when you're trying to get people to perhaps show a bit of innovation, creativity …” Going by assertion made by McDonald and Karg (2014) on allowing and managing co-creation in sports, with involvement, a team is able to stir creativity, engage, collectiveness, and encouraging positive group norms. Participant D pointed out that involvement of players in discussing and evaluating strategies in groups and subgroups “…we have this big list and then we put them in groups and then say, we break it down, and then we break it down again. So we do that with about five or six things that we felt was what was important to us …” The participatory approach in decision making such as group leader selection means values, ideologies and approaches propagated are collective: “…our leadership group that was voted by you that come back with the most votes, … we talked about characteristics and maybe change a team…”. This, as indicated by Wright et al. (2016), advances togetherness and collective approach in bot strategies development and addressing faced problems. Additionally, engaging the players creates a platform where both the players and coaching staff can interrogate the strategies together criticising and improving on it as well as getting them to know each other better. Participant D stated, “…the characteristics that make up a championship team and coming out togetherness, so they're bonding...” However, as a leader, the must be a balance in collaborating with and empowering player and coaching staff. A leader must assert leadership and direction but also ensure all the team members are on board and their voices and input taken in account. Participant B stating, “…I think if people are motivated by the vision, not by their paycheck, but by the vision and wanting to come into work and feel part of something and feel that they can contribute. I think that's when you really grab people…” Although disagreement may arise in a team, a collaboration towards a consensus is necessary. However, a line has to be drawn, noting that, “…If you wait for perfection and over collaborate, I don't think you'll ever get anything done. So there's that balance between weighing up collaboration, empowerment” An comprehensive structured engagement system that identifies with team values, ideals, and traditions is instrumental in ensuring right information is passed effectively across all involved stakeholders.

Team Dynamics

Player and team developmental aspects as well as outcome lies on interconnection and interlink between various variables. However, as highlighted by REF, an effective team is composed of several elements variables including diversity in team members that have to synchronise. For high performing teams, as noted by Participant B, diversity in terms of background, nationality, ethnicity, gender, experience, thinking, skills and age brings different perspectives in problem solution, quality, approach to strategy, and importantly understanding of subject matters such as players’ values and beliefs. Stating, “…you probably want a bit of diversity. So you might have an experience chief scout or an experienced member of the recruitment team that's been in it for 30 or 40 years, but then you probably want a young one young whippersnappers coming through that understand social media understands numbers and data and analytics, and how young players think now, and that's important. And yet that person clearly probably wouldn't have the subject deep subject knowledge and expertise, because they're new to it”. Diversity in both players, coaching staff as well as supporting members: different jobs and personalities. According to Tekleab et al. (2016), functional diversity inducing contextual aspects in team strategy, structure, and thinking influence positively cohesion and team performance. McDonald and Karg (2014) pointed out that diversity grounded on knowledge of both favourable and unfavourable processes, mastery-focused behaviours, and competencies offers insight into specific actions and strategies geared into promoting performance. As pointed by Participant C, as a coach, one has to accept some personalities are accepted and other influence but cannot mould all the players to fit required or perceived values and beliefs. However, fundamentally, a common goal has to established, stating, “…a common purpose in the dressing room, without it being nailed and blasted on walls and rammed down the throats. We had a more than a bigger core or a big call of young hungry players, that wanted to improve that wanted to get better that spent time on the training pitch”. In accepting personality diversity in the form of thinking, values, and beliefs, a team need to cultivate a shared norms and traditions in order harmonise individual and team’s goal, and hence developing a common strategy and implementation plan. Moreover, as part of team dynamicity, participants highlighted credibility and integrity as part of core variables influencing performance. Ownership of the group leadership by allowing the group members to select leaders who have values that resonate with them and then honouring the pick irrespective how it goes “…I'd already picked the captain. and so we're picking the leadership group. And so the next day I looked at I looked at all the results, and the captain didn't have hardly any votes … I said, we've got a bit of an issue. And he said, I didn't get any votes on it … and I said, And I said, Well, you have to address the group”. According to Participant D, coaching staff have responsibility and duty to draw strategies, plan, and instruct players in respect to both tactical and technical aspects of a game. However, this is grounded on connecting team various variables together to form a cohesive team. Participant D stating, “…we sell ideas to the to the player. So we need to have to have to be …, these five topics, connect to each other”. According to Participant C, although input of the players is encouraged particularly in game preparation and tactics, there are limits, stating “…you know, but in terms of tactics, strategy ... We do give them space. Yes, but there is a limit. You know… don't share the management”. Findings by Sarkar and Page (2022) on developing team resilience argued that athletes flourish in an environment modelled around personal qualities, shared responsibilities, social identify, team learning, and positive emotions interactions. Similarly, Ronglan and Aggerholm (2014) argued that cultivating an environment drive by ease interpersonal relationship including adoption of ‘humorous coaching’ establishes a balancing acts between ‘authenticity and performance’, ‘closeness and distance’, and ‘fun and seriousness’. However, Morgan et al. (2019) pointed that team resilience is defined group structure (such as communication framework), social capital (relationship and high quality), collective efficacy (shared belief for future success), and mastery approaches (collective commitment to learning and improvement) (Morgan et al., 2017; Giannoccaro et al., 2018) As such, resilience encompasses of psychological process protecting a team collectively from potential internal and external factors that might disrupt and affect negatively the outcome. It is worth noting that resilience is both multidimensional and multifaceted that not only involves ability to absorb change but also retaining stability once exposed to turbulence and perturbation such as poor performance. Meneghel et al. (2016) further illustrated that resilience is salient in a sport team and it is guided by dynamic process defined roles, responsibilities, resources, and composition of team members. Findings indicate correlation between team resilience, demands, and resources to performance. According to the participants, a high performing team is essentially driven by ability to withstand change, poor performance, turbulence, and disruption. Participant E noting, “…I need to create complexity a little bit more higher has to achieve, to give them in success. To put them focus in on thing is … when they can feel and we can talk about it, we need to adjust because you cannot keep going with that direction. Because you can create a lack of confidence as well…” Therefore, in addition to addressing challenges faced collectively, show vulnerability as well as navigating changes faced but driven by an ingrained team mission.

Leadership Style