Managing Uncertainty in Supply Chains

Chapter 1

1.0 Introduction and background of the study

In brief, the supply chain refers to the upstream and downstream flow of products, services, finances and information and constitutes a network of companies (Chopra & Meindl, 2016). Any material, financial or information risk could create problems within a supply chain and will cause delay and disruption (Buzacott , 1971).There is wide acknowledgement of the risks and uncertainties in global supply chains, the four suggested categories of risks in literature are supply, demand, operational, and security risks (Christopher, 2004). Likewise, Tang & Tomlin (2008) focused on the three major types of risks supply, process, and demand which are inherent to all different supply chains as shown in figure 1. Furthermore, the key aspects of risk can be listed as follows: uncertain customer demand, uncertain supply, uncertain yields, uncertain lead times, and natural and man-made disasters (Boulaksil, 2016). The efficiency of supply chain modes shows how various market uncertainties might affect investment and efficiency of supply chain performance (Lai, et al., 2009). In general, supply chain risks can arise either as high-likelihood, low-impact risks or low-likelihood, high-impact risks (Kleindorfer & Saad, 2005).Therefore, disruption caused by all these types of risks and uncertainties have a major influence on the flow of tangible and intangible assets in the supply chain and require preparation and precaution, otherwise it takes time for the affected system to recover (Hendricks & Singhal , 2005).

Uncertainties have been observed in many areas particularly in supply chain and these need to be continuously monitored and managed (Heckmann, et al., 2015) The turbulence and uncertainty of the markets encourage the implementation of strategies to make the supply chain more risk-resistant (Christopher & Lee, 2004). The awareness of risks related to the supply chain is well covered in literature, and it is accepted that urgent solutions are needed to avoid critical crises (Jüttner, et al., 2003).Since the supply chain disruptions are unanticipated and harmful events and causes inconvenience to companies, a massive surge for mitigation strategy regarding supply chain disruptions and related issues to prevent the potential financial and economic affects in advance is mandatory (Craighead, et al., 2007).

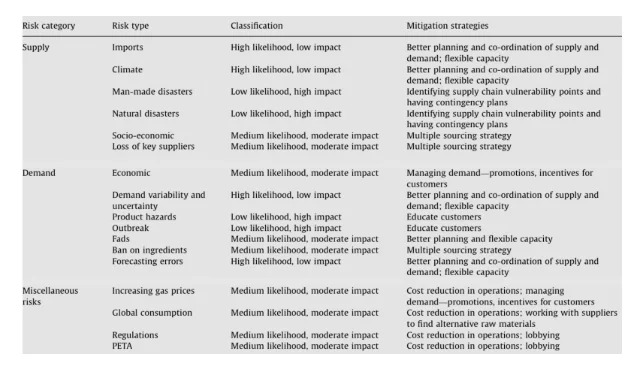

To achieve supply chain goals, such as, sustainability and continuity in the market, it is important to proactively manage supply chain risks due to external disturbances, such as wars, terrorist attacks, natural disasters, internal political conflicts, supplier bankruptcy, to name a few, that disrupt the flow of tangible and intangible assets in the supply chain (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). These major disruptions are impossible to predict and reveal a lack of preparedness of developments to secure the market during these periods (Heckmann, et al., 2015). These challenges and threats can undermine the stability and security of the business and make it hard for the firm to compete (Annarelli & Nonino, 2016.). Therefore, supply chain management seeks to establish strategies to address the risks and their potential impacts on the supply chain. Researchers concerns of risk disruption aimed to develop approaches and assessment to find treatment of vulnerability (Trkman & McCormack, 2009). However, Chopra & Sodhi (2004, p. 55) state that “Unfortunately, there is no silver bullet strategy for protecting organizational supply chains. Instead, managers need to know which mitigation strategy works best against a given risk.” Therefore, resisting the obstacles of uncertainty can be done by examining the market and decide the proper strategy to eliminate the consequences according to the market situation. Table 1 shows different type of risks and the proper mitigation strategies (Oke & Gopalakrishnan, 2009). As the literature analysis reveals, approaches have paid much attention to mitigation and contingency strategies of supply chain risk so far to secure the proper inventory, supply and demand planning within the chain. The reliance on reducing the risk in supply chain involves the importance to explore risk factors which may impact the market. For these risks, effective responses are a necessity. Risk mitigation and contingency response tactics are two essential plans according to (Tomlin, 2006). He discussed the major difference between these tactics as a mitigation plan reduces the probability of impact of the identified risk in advance of a disruption while contingency plan do not change the probability or impact of the current risk, instead it plans to control the impact as event disruption occurs (Tomlin, 2006). In some markets, it might be recommended to plan both the mitigation risk response and the contingency response alongside. Zolkos (2003) mentioned that successful companies are the ones who capable to identify and develop contingency plans for the various risks that exist internally and externally to the organization. According to Chopra & Sodhi (2004), managers constructing a supply‐chain risk management strategy need to consider the following, first, the creation of the wide understanding of supply‐chain risk next, the determination on how to adapt the risk‐mitigation approach to the circumstances of the particular company. For instance, disruptions and delays are two common types of the supply chain risks, the identification of drivers of these risk categories and the discussion of the implication of the risk mitigation strategies can reduce one type of risk but on the other hand it might increase another type of risk (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). Therefore, establishing the suitable strategy after addressing the risks and their potential impacts on the supply chain for the certain company in a certain market is very essential.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

The goal of any company is to obtain the highest possible return for their investments. For years, researchers have explored the ways in which markets can be enabled to achieve the greatest and highest profits possible. With the world becoming increasingly globalized, international markets and especially emerging markets, have been proven to offer investors more options to diversify and expand their investments. Middle East markets have been recognized as a region of recent economic growth and stability (Jones, 2003). The fast-growth of the region, due to its abundant supply of resources, and is currently proving to be an attractive destination for different types of businesses such as electronics and mobile phone businesses, with many brands now being represented in the region’s markets (AlGhamdi, et al., 2011). Academic analysis of the region’s geographic prospects have considered the following countries: Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Yemen, as part of the Middle East region (Jones, 2003). The prominent example of this study is Iraq’s market. Unfortunately, within this region, despite early optimistic view of economic conditions, some countries have experienced political tensions, which have dimmed the market optimism related to these countries (Chau, et al., 2014). The impact of political uncertainty and the recent turmoil in the Middle East region contributes to financial volatility in the markets of these regions leading to incapacitate the supply flow (Chau, et al., 2014). While it is a truism that all countries of the world are prone to uncertainties, in some countries uncertainty is rather more marked, causes disruptions in the timely delivery of products, and raises the requirements for business plans that anticipate uncertainty of the market (Handfield & McCormack, 2007). In 2004 the Iraqi market started attracting foreign and local investors to make significant contribution by investing heavily in its market. In the previous years, more and more electronic and mobile phone companies have internationalized their operations and targeted the Middle East and especially Iraqi market (Bradley III, et al., 2010). Besides, the cultural, political and economic diversity in Iraq’s market makes it attractive and profitable (Bradley III, et al., 2010). Consequently, international companies to benefit from the current situation and demand in Iraq by entering and developing this growth market early and ahead of others. However, foreign companies’ entry decisions in Iraq are surrounded by so many risks to secure and deliver the stock to the market due to political issues. This paper examines the risks to business due to the political turmoil and uncertainty in Iraq, which makes the market status impossible to predict. The industry observers agree that potential disruptions due to war and conflicts such as in Iraq situation pressures and interrupt the global supply chain ( Baljko, 2003). The challenges posed to supply chains within Iraq market due to a turbulent environment such as political conflict and external influences such as terrorist attacks can be categorized as “high impact and low probability risk”

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to Supply Chain Management and Profitability.

For instance, the government conflict is a major political uncertainty impact trading within the country and cause disturbances in changing systems and instability with other countries (Rao & Goldsby, 2009). Within the context of business plans, the importance of understanding the role of political uncertainty on management stability are of great significance to investors and market inspectors (Chau, et al., 2014).Therefore, uncertainty of Iraq market cannot be neglected and requires the implementation of mitigation techniques to improve the performance to reduce the uncertainty and conflict outcomes, aiming to enhance the supply chain performance to be proactive rather than reactive.

1.3 Research Aim

According to Tang & Musa (2011), disruption whether from nature disaster, terrorist attacks, and crises halt the complicated supply chain network and have consequences in loss of profits, and damage of markets share which requires preparation, precaution and inevitably increased the importance of supply chain risk management. The selection and developing of disruption strategies must be closely relates to and matches the firm’s profile and priorities. Whether it is the mitigation tactics in which incurs the cost of the action regardless of whether a disruption occurs or not or the contingent tactics which arise only when disruption happens and avoids any pre-investment on any sort of redundancy (Tomlin, 2006) This paper was motivated by a supply risk, which occurred in Iraq, one of the strategic markets of the Middle East; where the country is facing high supply risk due to political conflicts and unpredictable terrorist attacks which leads the companies to manage the high shortage of supply caused by unpredictable rules and regulations by the government. The focus is on electronics and mobile phone industry in Iraq market to derive principles of best practices and makes recommendations that will ensure the reduction of losses due the market instability. Despite these businesses deals with non-perishable products, this industry target substantial supply chain risk strategies for avoiding shortage in stock as well as obsolesce of the stock. The case study of a company which perform in Iraq, demonstrates the issues of the supply and how it is essential to manage stock to ensure the supply of demand while keeping losses due to uncontrolled risk at a minimum due to uncertainty caused by unstable market’s circumstances. The research methodology addresses the case of the Iraqi electronic companies through in-depth interviews and a case study of one of the companies that perform in Iraq market aimed at seeking insights for the approaches and strategies to hedge against uncertainty.

1.4 Research Objectives

To investigate the different types of strategies used to manage supply chain risks in Iraqi markets

To explore the process of selecting strategies used to manage supply chain risk in Iraqi markets

To explore the challenges associated with the implementation of strategies to manage supply chain risks in Iraqi markets

1.5 Research Questions

What are the different types of mitigation strategies to manage supply risks in Iraq market?

How the firm can select the strategy? What factors put in consideration before the selection?

What are the challenges associated with these strategies?

1.6 Justification of the Study

We intend to contribute to knowledge in this area by addressing a key question in an actual setting based on the data gathered from in-depth interview and the case study including:

Chapter 2

Literatrue Reivew

2.0 Introduction

The main purpose of the literature review section is to search and evaluate the available literature that will support and clarify the principal aim and objective of the study. The major aim to know different types of mitigation strategies to manage supply risks in Iraq market and what is the criteria for the selection and the factors the firm needs to take in consideration before the selection as well as the consequences of the selected strategies on the firm. First we need to define the different types of risk disruption that effect supply chain in Iraq market, which will help to provide the mitigation strategies required to manage these risks which are suitable for the Iraqi market. Based on the literature review, there are various risks in supply chain which identify as the following: material, information and financial flows, which are necessary in operating a supply chain regardless of the simplicity or complication of the chain as shown in Figure 2. In this paper we will focus on the material or products flow issues and risks within the supply chain.

2.1 Risks in Literature

In the field of supply chain management researchers face different set of challenges to create, and keep, efficient and effective supply chain methods and solutions, understanding comprehensively the risks which must be identified and quantified in order to control and mitigate considered as additional challenge in their list. (Wagner & Bode, 2009) distinguished the nomenclature related in the domain of supply chain risk management as following: Supply chain risk, supply chain disruption, supply chain risk source, and supply chain vulnerability they illustrated how these types are connected with each other as shown in Figure 3. According to (Tang, 2006) the literature correlated with identifying risks is in primeval stage while the research on managing risks is moderately developed. On the other hand, (Wagner & Bode, 2009) discuss how several publications define supply chain risks and distinguish them as either danger and opportunity or as purely danger. Similarly, (Schmitt & Singh, 2012) view firms who maintain operations with higher risk levels to have higher opportunities for being competitive. The academics and practitioners had great interest to examine different types of supply chain risks and disruptions and the related issues along with them as shown in Table 2 (Craighead, et al., 2007). (Heckmann, et al., 2015) identify core characteristics that drive the supply chain risk to the objectives that need to be accomplished by the underlying supply chain and the degree of achievement as well as the exposition towards the unexpected and uncertain developments. While (Tang & Tomlin, 2008) argue that the complexity of supply chains is the main reason to be more vulnerable to disruptions. They discussed three types of risks and all the associated risks along with each one, First the supply risk including cost, quality, and commitment, Next the process risks including quality, time, and capacity, third, demand risks specially the demand uncertainty (Tang & Tomlin, 2008). In the contrary (Schmitt & Singh, 2012) argue the goal of firm's management to be risk informed rather than eliminate the risks. (Craighead, et al., 2007) adopted the perspective that all supply chains sooner or later will experience unanticipated events that would disrupt the flow of goods.

2.2 Material Flow Risk

The scope of this paper is to investigate the material flow, which basically involves physical movement within and between supply chain elements. There are different types of inventory, it can vary from raw materials to works-in-process and finished goods, as well as maintenance, repair, and operations products (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). In this paper, focus is on the third type of inventory, which is the ready to be sold products. Inventory is a fundamental measure of the strength of supply chain management (Chopra & Meindl, 2016). It is considered the capital asset for any supply chain, whether it is a global or domestic firm (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). As part of supply chain, inventory management includes essential aspects such as controlling and overseeing products not only from suppliers’ end but also from customers side to maintain storage, control inventory, and order fulfillment. Hence, inventory planning and controlling is crucial to establishing appropriate supply to the market demand. Planning includes the amount of time, effort, money and other resources expended on inventory to ensure the sustainability and resilience of the supply (Partovi & Anandarajan, 2002). Lack of inventory management can lead to a situation where the firm is burdened with obsolete, redundant, or surplus stock which unfortunately requires extra money to manage due to the storing and controlling of the products (Partovi & Anandarajan, 2002). This scenario occurs when uncertainty is highly unpredictable and leads to shortages or surplus in stock and causes stockholding, which can cause more damage, such as, loss and deterioration of stock (Partovi & Anandarajan, 2002). Therefore, inventory management contributes to maximizing value and reducing risk and uncertainty (Michalski, 2009). According to (Chen, et al., 2007) the behavior of some inventory planners as risk aversion, where the main idea is to make decisions based on inventory position, on-hand inventory level and inventories in transit. Knowing the stock level in all the channels is mandatory to plan it properly. These strategic behaviors are used to streamline inventories across the supply chain and to keep the inventory investment and risk involved as low as possible. The risk portfolio of a firm’s inventory is a system integrated within the chain according to (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008), which provides the firm with a methodology to prioritize cost and risk elements to flag a risk in advance and to prevent it from occurring. Tang & Musa (2011) discuss the perspectives of risks along with the material flow as three stages of source, make and deliver and acknowledged the interconnection of these flows and how one of these flows can obstruct the other ones . First, the stage of source involves different types of risk issues such as single sourcing risk, sourcing flexibility risk, supplier selection, outsourcing, supply product quality and supply capacity (Tang & Musa, 2011). However, the variation of choices and concerns in the source stage can either bring a hidden cost and managerial difficulties or reduces costs and improves responsiveness dependences on the firm decision. Second the make stage involve product and process design risk, production capacity risk, and operational disruption. these risks occurs with the inability to cope with the market and technological changes, and operational contingencies, natural disasters and political instability also it could involves a high cost to the firm (Handfield, et al., 1999). Finally, deliver stage is significant since the risk issues are related to demand, seasonality, and excess inventory, therefore these issues are all affected by rapid technology evolvement and customer demand changes and short product life (Tang & Musa, 2011).

2.3 Mitigation Strategies

The proactive supply chain strategy against the disruptions has been the subject of significant debate and discussion since supply chain disruption can potentially be harmful and costly and often represents a significant risk to an organization. Firms are required to build resilience strategies since the supply chains are becoming more complex and the severity and frequency of disruptions within the chain is increasing exponentially. (Craighead, et al., 2007) discussed how disruptions vary in severity and are unavoidable in supply chain, they encouraged the firms to consider some factors that could contribute or detain the disruption severity and its consequences before implementing any strategies or policies. The main factors of supply chain according to (Craighead, et al., 2007) are supply chain density, complexity, and node which are related to supply chain disruption severity. (Craighead, et al., 2007) discuss how supply chain mitigation capabilities and supply chain design characteristics, can interact in determining how severe a disruption would be within a supply chain and also how they can moderate the impact that supply chain density, complexity, and node criticality have on supply chain disruption severity as shown in Figure 4. The firms need to know whether to accept, avoid or limit the risks by first outweigh the cost of the disruption, next the possibility of disruption occurring and finally the implementation of the more suitable strategy of the firm and the environment surrounding. Kouvelis et al (2006) argue for the importance to quantify the risks via systematic approach by encouraging the firm to invest in resources. Schmitt & Singh (2012) encourage the firm to be aware of its supply chain risk levels then evaluate its investments and make decisions based on its own level of risk tolerance instead of any pre -investment in any mitigation strategies. While Kamalahmadi & Parast (2017) encourage an incorporation different types of redundancy practices such as pre-positioning inventory, backup suppliers, and protected suppliers into a firm’s supply chain that is exposed to supply risk and environmental risk and adding contingency plans, they can help to mitigate the impact of supply chain disruptions as well as reduce costs and risks. However, some firms still focus on reducing cost and increasing reward, and not paying attention to risk mitigation. Braunscheidel & Suresh (2009) argue that agility in supply chain is a valuable approach for both risk mitigation and response since the marketplace nowadays are intensively competitive and suffer from high levels of turbulence and uncertainty. Similarly, Culp (2013) discuss the importance of the supply chain structure to be adaptable and agile in respond to the market conditions in order to be responsive when the disruptive event occurs.

2.4 Different Mitigation models

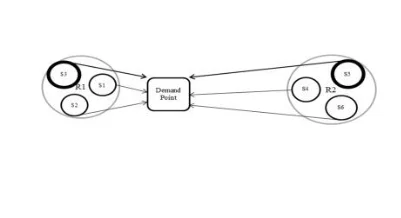

Industrial and academic aspects increase the awareness of risk management issues and raised many research questions on how to compete and enhance the supply chain to cope with all the new challenges in the field of business and environment changes. Most literature research focuses on material, cash and information flows issues in risk management hence, risk mitigation techniques have been investigated and modeling techniques have been analyzed to examine the risks in these areas. For instance, Tang & Musa (2011) believed that improving a supply chain competence in the new business environment can be achieved by developing risk management models. Also, Tang & Tomlin (2008) examined different flexibility strategies in the context of supply chain risk management to illustrate the power of flexibility for reducing supply chain risks. Their models were motivated by different degrees of flexibility to mitigate supply, process, and demand risks were some of the stylized models were based on work presented in the literature (Tang & Tomlin, 2008). In this section we will present some of the problems and the models discussed in literature and emphasize the differences among these models. The explanation based of the general problem under supply and environmental disruption risks, and development of different models based on variety of circumstances. Kamalahmadi & Parast (2017) developed a two-stage mixed integer programming as a General Model to address the problem of supply and environmental risks, where they examined the supplier selection and order allocation under supplier dependencies and risk of disruptions then developed three separate extensions of the General Model, to evaluate the expected cost of each one of three risk management mitigation strategies: pre-positioning inventory, backup suppliers, and protected suppliers. The General model as shown in figure 5 designed for the firm to minimize the total cost and the negative financial impact of disruptions therefore, the firm needs to select the supplier and the region since it is considered a global supply chain where suppliers are spread around the world. There are h possible suppliers, H={1,…,h} the suppliers are distinguished as separate sets in region r, R={1,…,r}, where the firm has only one facility and the total demand per cycle is Q. The characteristic of the General Model’s uncertainty is independent and happen in suppliers and regions separately or concurrently where a supplier is disrupted and /or unavailable depending on two conditions first an individual disruption happens to the supplier second condition if an environmental disaster happens in the region in which it is located. The first stage in the General model decisions are determined through incorporating uncertainty of the future outcomes and included supplier management cost while the second stage decisions are evaluated after the potential future outcomes are assessed and included order cost, transportation cost and loss cost. The main objective function in both stages are the minimization of all these four different types of cost.

First, Kamalahmadi & Parast (2017) designed the Pre-positioning Inventory Model which is an extension to the General Mode as shown in figure 6. They assumed the warehouses’ characteristics as following: the firm has the ability to build warehouses in different regions, there are options of location of each warehouse, and each warehouse has a specific capacity, fixed building cost, defined transportation cost and holding cost per item pre-positioned in warehouse. As shown in Figure 6 the variables R1 and R2 represent region, S1 to S6 represent suppliers and W represents the warehouses. Where the solid arrows define the delivery paths, the orange dashed arrows define the delivery paths for pre-positioning inventories prior to disruption and the black dotted arrows represent delivery paths in disruption when emergency items are transported to the demand location.

The cost associated in this model according to (Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2017) are in first stage: the supplier cost, warehouse building cost, emergency inventory order cost , emergency inventory transportation cost from suppliers to warehouses ,emergency inventory holding cost. Second stage contains more costs such as the order and transportation costs from suppliers for purchasing and transporting the normal allocation of each available supplier, emergency inventory transportation cost from warehouses for transporting pre-positioned emergency inventory from warehouses in order to make up for disrupted suppliers’ allocations. Finally loss cost for the items that remained unsatisfied at the end of the cycle. Second model developed by Kamalahmadi & Parast (2017) is the Backup Suppliers Model as shown in figure 7. The main change in this extension is the firm divides suppliers into primary and secondary suppliers. Primary are the main supplier during normal circumstances while secondary suppliers are the backup during disruption only. In figure 7 the solid arrows are flows of suppliers in normal conditions while the dotted arrows are flows of emergency inventory from backup suppliers during disruptions periods.

Kamalahmadi & Parast (2017) mentioned the main characteristics of Backup model is prices of the product where the supplier will have two different prices during the normal situation and another price during the disruptions where the disruption price assumed to be higher than the normal price. The decisions are the selection of backup suppliers, the allocation and quantities of emergency stock in each scenario. For this model the associated costs are divided into two categories. First stage costs are supplier management cost, backup contracting cost and emergency inventory holding cost for the second stage costs are: order cost and transportation cost emergency inventory order cost and emergency inventory transportation cost and loss cost. Final model developed by Kamalahmadi & Parast (2017) is the Protected Suppliers Model, where the firm improves the reliability of its suppliers by investing and allocating emergency inventory to protect a supplier to minimize the disruptions as shown in figure 8. On the other hand, the proposed model for disruption with protected and unprotected suppliers where the bolded arrows emphasize the protected paths to the protected suppliers. Each protected supplier has an emergency capacity and sells the emergency stock at higher than the selling price. The firms need to determine which supplier to protect and the quantity of emergency items to avoid the disruption shortage in supply. The associated costs for each stage are similar to the Backup Model in addition for the first stage is the protected suppliers cost.

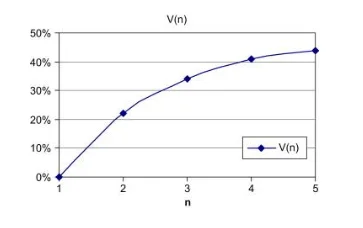

(Tang & Tomlin, 2008) focused on strategies that are based on the agility principle with supply, process, and demand risks. The investigated strategies were based on flexibility in order to reduce the negative implication within the chain. They presented five separate models to examine a fundamental of flexibility to manage supply chain risks without the consideration of the cost for implementing additional flexibility in any of the models. In this paper we will discuss the models related to the supply risk. Tang & Tomlin (2008) studied the power of flexibility via multiple suppliers model which was motivated by the flexible supply strategy adopted by Intercon Japan. The circumstances of the situation based on five suppliers with uncertain supply costs and the assumption of identical and independently cost, the supplier who offers the lowest cost is chosen where the supply flexibility level represented by the number of qualified suppliers. Figure 9 illustrates significant savings due to the power of supply flexibility via multiple suppliers where V(n) is the percentage of savings in unit cost by ordering from n suppliers, V(n)=(UC(1)−UC(n))/UC(1). As shown V(n) is increasing and concave in n which proof the reduction of supply cost risks, and encourage to order from a small number of suppliers.

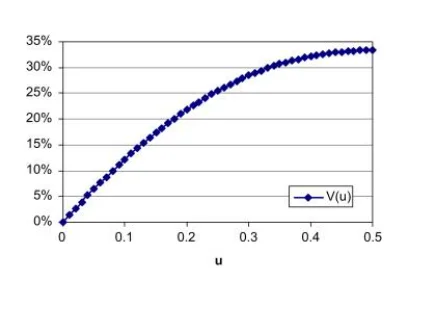

Tang & Tomlin (2008) discussed the supply commitment risk in this model they illustrate the power of flexibility via a flexible supply contract as one of the strategies, this model was motivated by a supply chain network comprising the supplier Canon, the manufacturer HP, and the retailer Best Buy as shown in figure 10. The ordering process is when the retailer places the order end of the period while the manufacturer places it at the beginning of the period from the supplier.

At the beginning of period the estimated order D=a+ε by the retailer

a represents the forecasted demand

ε corresponds to the uncertain market condition during period.

manufacturer orders x units at the beginning of period where x is a decision variable and would depend on the flexibility level of the supply contract engaged between the manufacturer and the supplier.

u-flexible is the supply contract where the manufacturer is allowed to modify his order from x units to y units y must satisfy: x(1−u)⩽y⩽x(1+u), where u⩾0

As shown in figure 10 V(u) is increasing and concave in u. Also, significant benefits associated with the u-flexible contract can be obtained when u is relatively small. This may explain why HP was satisfied with a flexible supply contract with Canon based on a small value of u

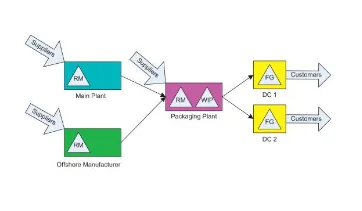

Schmitt & Singh (2012) conducted a model with the CPG firm and referred to it as company ABC in their model to study the risks in their network. As shown in figure 11 model ABC's network is an assembly distribution system, the network contains two distribution centers, one packaging plant, and two manufacturing plants. Respectively, RM, WIP, and FG stand for raw materials, work-in-process, and finished goods where WIP inventory is unpackaged product and inventory locations are represented by triangles as shown in the diagram. The operation of the model is with a base-stock level at each product level. The operation target is to accomplish one week of RM inventory, two weeks of WIP, and finally four weeks of FG.

The model of Schmitt & Singh (2012) developed risk profiles of all parts of supply chain, and considered transportation disruptions from the offshore manufacturer in their model, since the interruption of the flow can be caused by the long lead time and customs issues. In their paper they discussed the disruption categories for each location and how they generate them from interviews and literature. Also, they tested inventory placement based on realistic disruptions in the network and used simulation model to allow the observation of the system performance. Based on a multi-echelon inventory, the disruption impact on inventory placement and volumes in three levels (i.e. RM, WIP, and FG) of inventory storage, which are held at each levels of the supply chain (Schmitt & Singh, 2012). The accurate holding cost structure for ABC was studied by them in order to assess the impact of the disruption and outlined in Table 3. Their analysis demonstrate the importance of the firm to design a system that focus on upstream and downstream location in order to solve the optimal inventory level and be resilient to disruptions and stochastic demand. The simulation of the supply chain proofed the dynamic nature of disruption and its impact on inventory levels. The flexibility built into a system via inventory throughout the system reduce the disruptions and the impact along with minimizing inventory to reduce cost, but should be undertaken with a careful consideration to manage both demand supply to avoid any chain risks.

2.5 Findings of different models

The most important finding for Kamalahmadi & Parast (2017) that the three models developed by them proofed to reduce costs and risks compared to the General Model. Each model assisted to examine the impact of mitigation strategies in sourcing and procurement decisions. Next each model analyzed and provided depth insight to the selection of the proper supplier, demand and capability based on the reliability, risk, dependence and cost in order to reduce the severity of the disruptions. Finally, the environmental disruptions can be mitigated by regionalizing a supply chain and reduce the impacts of the risk within the chain it also enhanced the understanding of the supply chain risk management. Tang & Tomlin (2008) focused on various flexibility strategies as defense and proactive mechanisms for mitigating supply chain risks and away for firms to compete in market. They are encouraged to implement the limited flexibility strategies in order to reduce supply chain risks significantly. Also examined and provide different models to illustrate the robustness of power of how low level of flexibility is enough to mitigate and reduce supply chain risk which encourage firms to build flexibility within the supply chain. The finding by Schmitt & Singh (2012) shows ABC model of the supply chain has multiple echelons view of system and reflect realistic disruption risks, and different mitigation strategies to make inventory decisions more accurate and the insights clarify the understanding of holding cost structure which help to generate the best inventory design and can be reasonably extended to more complex supply chains. The model demonstrated a systematic approach to control the downside of a disruption

2.6 Limitation of Different Models

Kamalahmadi & Parast (2017) stochastic models and experiments have several limitations such as the values for parameters may not accurately capture the dynamic nature of supply chains where the supplier and regional disruptions is the core of their study. Furthermore, they neglected a time horizon in any of the three strategies. The models were assumed to be performed in a one cycle demand period without backlog. Tang & Tomlin (2008) presented different models of flexibility strategies with lack of reliable data and accurate cost due to limitations of data availability. The implementation of any of these strategies or a combination of them will not eliminate the urge to structure the evaluation process such as the mitigation and contingency planning, risk assessment and identification. Schmitt & Singh (2012) mentioned the benefit of proactive planning and mitigation in transition into emergency and recovery operations within the supply chain smoothly. ABC model results indicate that mitigation strategies employed in the inventory decision and explored the reduction of risk at different locations in the network however, if the rest of the network is too vulnerable and contain weaken links in the chain then these strategies will not be enough unless an improvement is implemented to strength the weaken parts of the chain. The improvement of the overall resilience of the system cannot be done by the strategies only where the firm need to invest the time proactively to understand the parameters of the disruptions and when the expectation to occur in order to minimize the impact of it in the network.

Chapter 3

3.0 Research Methodology

Research is the foundation for knowledge, innovation and application to provide broader benefits for supply chain and inventory management in this area. The methodologies that guide and support risk inventory management evaluation vary depending on the approach and method preferred by the researcher and the real benefits and impacts of the different methods used involve providing data, knowledge and insight to solve a particular problem or to explore an unknown phenomenon. In addition, the methodologies can be considered diagnosis tools that allow researchers to appraise information related to safety stock; however, some papers used data collection to support the understanding of meanings, beliefs and experiences, while others collected data based on accordance with certain research vehicles and underlying research questions. Some studies do combine quantitative and qualitative methods, which are useful in generating data (Creswell, 2013, p. 12). This is considered a common approach, and it supports the set of findings from one method of data collection with another method underpinned by another methodology (Creswell, 2013, p. 12). There is increasing interest in SCRM within the academic and industrial environment, and there are several academic journals and resources on topics related to it (Al-Najjar, et al., 2016; AlGhamdi, et al., 2011). However, scholars originating research in Middle East market face so many challenges in conducting research, first the data collection included validity and reliability issues, second the language barriers and the diversity of the region, third, lack of research support infrastructure (Lages, et al., 2015). Therefore, the case study approach was adopted as a useful method for exploring the areas and enabled to gain in‐depth understanding of a situation which is difficult to investigate using other techniques.

3.1 Data collection

The qualitative research design, based on interviews, was used in providing more insight into the issues faced by managers and the best practices that are followed by them (Yin, 2009). Using interviews, a significant amount of data were pre-tested and supplemented with findings from interviews with senior executives and managers in companies working in Iraq market. In this study, the primary method of data collection was through interviews of key sales and logistics managers from companies work with Iraq market. Interviews were conducted by online calls using Botim application to conduct and observe the interviewee answering the questions. Besides, Botim is as webcam application which is more flexible and obvious way for time and cost saving (Bryman, 2016). One researcher participated in each interview were individual interviews lasted between 45 to 90 minutes. Each interview was recorded, and transcribed for data analysis. After each interview, the urge to immediately discuss the interview observations, and to code and analyze the data collection proceeded to ensure the achievement of theoretical saturation of the qualitative interview method (Bryman, 2016). The secondary data collection included supporting material and figures from the participating company such as company profile, sales figure, Iraq’s ports rules and regulations, local newspaper articles, and internal processes. These materials are essential data from the participants to allow improving the understanding of the phenomena and increasing the reliability of the study (Bryman, 2016).

3.2 The interviews

The case was analytic as there were no known previous studies of supply chain risk conducted in Iraq market and focusing the case on a single company to improve the investigation in developing the research. The single case study was more appropriate for generating depth of information in a single product from a certain company to provide best practice of a company related to the uncertainty and has undergone a change of business and management structure during the period of risk to eliminate the consequences. Data were collected from 2018, to tackle the issue when it happened. Different people across different departments in sales and logistics were selected throughout the duration of the study to provide the data needed for the investigation. The advantage of this approach to pre‐specified single company and one single product to allow understanding the risk , the safety precaution and the key relationship in a setting which could reveal facets to be studied in another country within the Middle East. The company provided the research with a unique and revelatory data for the single case. The case started when the Iraqi Federal Government has imposed an international flight ban on the Kurdistan Region's airports on both the Erbil and Sulaymaniyah airports on Sep. 29, 2017, and lasted for more than five months. The flight ban effected the lives of many people living in Kurdistan and added unnecessary complexities for the access of cargo and vital imports to Erbil and Sulaymaniyah (BCC, 2017 ).The embargo was a turbulent for the company to maintain profits and deliver the goods to the customers in the Iraq market which proved to be a struggle. Due to the uncertainty the management structures have been restructured and the business philosophy has changed dramatically. This makes Iraq market an interesting case to investigate the management of risk and subsequently the issues of supply chain and how to manage the inventory and the safety stock in the channels of distribution. The level of participant observation taken was moderate to maintain a balance between participation and observation (Bryman, 2016). In this way the researcher was able to observe and be involved with managers and retain enough information to influence the investigation of the case study and gain better insight of the risk management that was implemented by the company. The prospect of getting close to the subjects in question was an advantage, to reduce the reluctant of information sharing, and develop trust to encourage the access of sensitive information. Also, enables capturing the emerging issues of risk that might prove to be invaluable or significant. In‐depth, semi‐structured and unstructured interviews were undertaken to gather detailed information (Bryman, 2016). These types of interviews allowed discussion to flow, and the conversation between the interviewer and the interviewee enabled the researcher to probe deeper and collect detailed data (Bryman, 2016)

Chapter 4

4.0 Results and Analysis

In this chapter, we describe the study findings and expound on what the respondents said that would help in answering the research questions. However, it is important to note that whereas the appropriate risk mitigation process involve an identification of the suspected risk, assessing it and establishing an appropriate mitigation plan, before monitoring the plan and controlling the plan, the responses did not cover all these four steps, but rather, a majority of the responses covered the operational strategies to supply chain risk management. Nonetheless, the interview results revealed supply chain risk management strategies that could fit into five major themes. The following table highlights the identified themes and their respective sub-themes, if applicable.

4.1 Inventory Management

When asked to explain some of the strategies they used to manage supply chain risks, a majority of the respondents mentioned that they either immediately or in due course implemented a strategic inventory management activity, whereby they deliberately held inventory for future use regardless of the disruption it would cause to the supply. For instance:

Respondent 1:

When we realized that one of our suppliers would reduce the volumes of their supplies due to financial difficulties, we held some of our inventories in preparation for the future expected fall in supply.

Respondent 2:

It was quiet challenging to us. One of our suppliers experienced a fire in their store and therefore could not assure us of business as usual, we had to hold back some of our inventory in preparation for the expected shortfall in manufacturing. Again, while this was totally not our fault, we had to develop some measures to cushion the uncertainty

Respondent 3:

I remember how our customers were disappointed with us, we had to manage our inventory in response to the expected delay in raw materials. But, this strategy was only successful because the suppliers had notified us in prior that they would not provide us with the usual quantity of raw materials

Respondent 4

There was nothing we could do, we had turned down all the offers made by potential suppliers, except for one supplier whom we through had the right specification of the materials we needed. In response, we had to reduce the quantity of products we could release to the market. Thus, we resorted to a tight inventory management strategy which saw us hold some of our inventory for a while till the supplier could get back to their feet again.

These responses indicate how inventory management can be used as supply chain risk mitigation strategy, whereby the inventory is held for a while in preparation for the expected production shortage, especially those attributable to suppliers’ inability to deliver the correct amount of raw materials. However, when asked to explain some of the major challenges experienced while implementing this strategy, some of the respondents mentioned that they experienced a difficulty in establishing the correct amount of stockpile to cover the risk severity. For instance:

Respondent 1:

As a manager in the inventory department, it was difficult for me to identify and make decisions on how much stock we would want to hold to cover for the period of time our production would be disrupted.

Respondent 2:

By the time we were evaluating the strategy, we realized that we had held back too much stock that were supposed to. And I remember us brainstorming on how much stock we needed to hold and it was just difficult to figure out

Respondent 3:

I tell you for sure, we couldn’t have accurate information on how long the suppliers would be in crisis, and so we could not tell the most appropriate level of stockpile we needed for our strategy

Therefore, identifying the risk profile, i.e. severity and likelihood is one of the challenges likely to be faced by managers when using the inventory management strategies. However, one of the respondents also mentioned that it may be difficult to adopt an ongoing risk identification system, and this may cause a challenge reduce the stockpile when risk is low or increase the stockpile when the risk is high. For example:

Respondent 3:

Unfortunately, we could not have a clear system of detecting the risk profile of the disruption to enable us regulate the stockpile according to the risk fluctuations.

Hence, risk detection is among the barriers for implementing inventory management as a strategy for supply disruption risk management.

4.2 Supply Diversification

Some respondents also mentioned that they diversified their supplies as a way of mitigating supply disruption risk. Particularly it emerged from a majority of the respondents that they contracted more than one supplier to ensure that they are cushioned from any disruptions, in case one of the suppliers fail to deliver the required quantity of supplies. For example:

Respondent 1:

We have always maintained more than one supplier, ever since we were disappointed by a single supplier back then, which messed our business so much.

Respondent 3:

We can no longer risk with one supplier, we often contract two or three suppliers for a single raw material just in case the other ones fail to deliver, and we have other options.

However, a few of the respondents noticed some challenges that are worth noting. One of the challenges that emerged was that of cost, whereby huge financial costs were incurred in the process of qualifying more than one supplier.

Respondent 5: sometimes we think it is less costly to just select one supplier and work with them the whole year, rather than having to undergo an entire process of qualifying more than two or three suppliers.

Even in the case of the company diversifying to use different supply points, the responses revealed that it is less costly to have one warehouse than have several warehouses in different locations. For example:

Respondent 4: We have to pay rent for all the warehouses, as opposed to other organizations that use a single warehouse for their goods.

These responses indicate the cost implications for diversifying inventory storage. In addition, some respondents complained that at times, it happens that the disruptions affect all the facilities and warehouses, making it difficult to minimize risk of disruption using the diversification strategy. For instance:

Respondent 2:

In one occasion, both our suppliers were under a financial crisis and could not meet our supply demands. At that pint we were doomed because we only had two suppliers then. This means that even sometimes when we try to diversify our supply, the suppliers may be hit by market risks, thereby exposing the entire market to disruptions.

Respondent 4:

There was an incident whereby all our warehouses were infested with pests because there was an outbreak of the pests here in Riyadh. We were unable to mitigate the risk of disruption t6hrough diversification because the both warehouses were affected. This had a great impact on our business.

Apart from the correlated disruptions that may affect diversification some respondents were keen to note the problem with inconsistencies, whereby different suppliers may bring varying supplies, thereby causing a problem with standardization and quality consistency. For instance:

Respondent 3

Sometimes it becomes difficult to standardize the quality raw material supplies from the two different suppliers that we have. In fact, there are times when we cannot tolerate the quality inconsistencies, and this creates a lot of issues with our suppliers.

4.3 Standby Supply

Further interviews with the respondents revealed that some organizations adopt a standby supply strategy; whereby alternatives not routinely used in the supply chain are temporarily relied on to meet the supply requirements when the primary source is disrupted. For instance:

Respondent 3:

Recently, we experienced a breakdown in our supply chain transport system, whereby all the trucks were down for repair. To address this disruption, we used rail transport as an alternative transport as a backup even though we do not normally use it.

Respondent 4:

Sometimes we rely on our staff’s vehicles to make deliveries when all our trucks are full or engaged.

Whereas standby supply strategy has clearly emerged as a strategy for mitigating disruption risks within the supply chain, further probing revealed that this strategy also has its challenges. For instance, the respondents noted costs, availability, and magnitude and response time as some of the key challenges experienced in implementing this strategy. For instance:

Respondent 3:

While we prefer the trains as an alternative when all the trucks are held up, the availability of the train is sometimes unreliable because it does not run on our schedule. We sometimes have to wait for more than 12 hours to have the next train arrive and pick the goods for delivery. In other occasions, the train might be available at the required time, but it may not take all the goods due to available capacity. Hence, when using the train, we are forced to supply less than what is required. Another problem we have faced with trains is that we sometimes incur higher costs of transportation that we would with our trucks. When the train operators realize that it is a matter of urgency, they charge us even higher.

Respondent 4

Whenever we resort to use employee vehicles for the supplies, we then ask the question of how quick can the employees respond, and whether the vehicles have the required capacity to carry the goods. This has always been a challenge.

4.4 Demand management

It is apparent that the above-mentioned three strategies deal with the supply side of the disruptions. However, some interviewees also mentioned strategies that entailed managing the demand side of the disruption. For instance, a respondent form the pharmaceutical industry noted that:

Respondent 1:

Sometimes we have to work with the government, patients, regulatory authorities, and health practitioners to mitigate the disruption risks. In doing so, we lies with health practitioners and regulatory bodies to achieve alterations in the treatment plans, thereby meeting the demands with the available supply. These alterations may be with regards to the types or amounts of drug products required.

However, the respondent mentioned that for effective demand management to be achieved, there need to be effective switching. With regards to the switching, the respondent noted that:

Respondent 1:

If we noticed that the customers are willing to switch from one product to the other, then we could use switching to mitigate disruption risks. However, this is only possible for products are not within the same production line, otherwise the disruption in the production line would make it difficult to switch to alternative product.

Another respondent revealed that sometimes they use the rationing strategy to control demand when there is a disruption in supply. For instance, a respondent from a domestic water supply agency noted that:

Respondent 3:

Another strategy that has been much popular in our supply department is rationing, whereby we induce a supply constraint based on the geographical area of supply. For instance, if area A received water in the morning hours, area B will receive water supply in the afternoon hours; and no area receives water supply at the time when the other area is receiving.

However the respondent noted that they encounter a challenge with striking a balance on how to fairly allocate the water supplies. For instance:

Respondent 3:

When rationing the water supply, we have to consider whether we might actually lose some customers to our competitors, or whether we have loyal customers whom we would retain regardless of the rationing balance. Besides, we have to ensure that the rationing timelines are well communicated to the clients so that they have time to prepare and to eliminate concerns over lack of supply. If we fail to inform them early enough, they might assume we are out of business and contact our competitors.

The study, therefore, has found that rationing as an element of demand management strategy requires proper balance and effective communication to execute; otherwise it would be hard to succeed with the strategy.

4.5 Developing a Stronger Supply Chain

Apart from the above-mentioned strategies that apparently seek to manage the impact of supply chains disruption, the interviews also revealed the existence of other strategies that anticipate for supply chain disruption and mitigates it before it happens, one of them being developing a stronger supply chain. For instance, one of the respondents indicated that they coordinate and lies with their suppliers to minimize the severity and frequency of disruptions:

Respondent 1:

Sometimes we do not work with multiple suppliers to address the disruption but rather anticipate the disruption beforehand and coordinate with the suppliers to ensure that the anticipated supply disruptions are minimized.

When asked about how they executed this strategy and whether they encountered any challenges in the process, the respondent mentioned that the key to success in the strategy is to develop a proper approach to the suppliers, ensure there is a proper timing fr the supplier to commit, and that there is an effective management of risk spillover. For instance:

Respondent 1:

We always have to think about how we can frame the supplier development in a manner that ensures their performance is capable of meeting our long-term and short-term supply needs. However, sometimes it might be difficult to have the suppliers commitment, and the efforts to improve the supplier performance might be challenged by internal shortcomings. Hence, we have t strike a balance between entering a contractual agreement with the supplier to commit now wait for future commitments. Besides, we have had interesting experiences with some suppliers whom in the process of working with them to improve their operations, the suppliers actually grow to become our competitors, a scenario we sometimes describe as a spillover.

Therefore, the responses above indicate that whereas improving the suppliers process in anticipation for supply disruptions is an effective strategy that helps mitigate the disruption risk before it occurs, the strategy can be challenged by several factors that may go as far as creating more competitors.

Chapter 5

5.0 Discussion and Conclusions

5.1 Discussion

Our results, through thematic analysis, has identified five significant strategies that can be used to mitigate supply chain risk; four that are applied after the threat has occurred, and one employed before the disruption. In a nutshell, these strategies include inventory management, supply diversification, standby supply, demand management, and stronger supply chain. In this chapter, we will discuss these strategies from a broader perspective, highlighting what existing literature says about them and their implications for practice. According to Durach & Jose (2018), the concept of inventory management, or stockpile inventory, is a strategy that is relatively simpler to implement compared to other strategies, and entails developing a creative way of choosing the inventory as a way of managing supply disruptions even if keeping the stockpile affects the organization’s ability to meet the current supply needs. But it might be impossible to immediately use the stockpile in case of a disruption, especially for perishable goods because the organization will have to prove that the products are suitable for consumption (Desai et al., 2015). Besides, a problem may emerge, whereby the organization might have kept a smaller volume of stockpile than required. Rotaru et al. (2014) postulate that such a scenario might arise when the managers underestimate the anticipated disruption. There is a corroboration between literature and this study’s findings that: whereas inventory management is a good strategy for mitigating supply chain risks, it has several weaknesses that should be taken into account before selecting it as a risk management strategy –as discussed below: In risk management, the risk severity and likelihood are two dimensions that must be considered by managers during management of supply chain disruptions. Some supply chain disruptive occurrences are rare despite having a high severity (i.e., occurring for longer durations). Others may happen more often but have a lower severity. Thus, it is vital to understand this distinction, especially when applying the inventory management as a strategy for disruption mitigation. For instance, Samira et al. (2018) argue that the severity of disruption determines the volume of inventory the company may need to respond to supply disruptions. With regards to frequent but less severe interruptions, the company will need to have a larger volume of stockpile inventory (Kwak et al., 2018). However, such a scenario would be associated with two challenges, namely temptation, and opportunity. While the company may afford the direct costs related to stockpile storage, keeping the large stockpile might present various opportunity costs that the company may have to incur. For instance, the company might have invested money in the stockpile, which is not turned into cash. While this expense might not be reflected in the income statement, it is a hidden cost that is associated with a low return on assets (Sodhi & Tang, 2012). With regards to temptations, managers may find it easier to maintain the stockpile in preparation for frequent but less severe disruptions. However, Zsidisin & Henke, (2019) argue that for severe but less frequent interruptions, managers might bear the disadvantages that come with lower inventory volumes but might not experience the benefit because the disruption has not occurred. Consequently, it may be tempting for the managers to release the stockpile inventory under the assumption that the disruption might not happen – because it has never occurred for a long time. In case of severe but rarely occurring disruptions, and managers might experience an economically unfavorable opportunity cost, making the strategy more economically unattractive. Besides, Olson (2012) argues that the temptation factor may make the stockpile strategy unsustainable, unless the organization has established a disciplined system ensuring that the stockpile is maintained. Contrastingly, the inventory management strategy can be useful in cushioning the organization against rare but severe disruptions. But according to Khan & Zsidisin (2011), the use of inventory management strategy to manage the risk rare but severe disruptions is achievable when the company is in particular set of circumstances makes the other strategy identified in this study even less useful.

As indeed mentioned in the findings section of this study, the use of inventory control strategy may also encounter the challenge of detection, which involves maintaining a stockpile that exactly meets mitigates the risk of disruption without overestimating or underestimating. This finding corroborates with the results of other studies and literature documentation. For instance, according to Zsidisin & Ritchie (2008), a primary characteristic of the inventory management strategy is that the company has to keep a large stockpile of inventory for a long time. Besides the stockpile has to be increased when the disruption is severe, or reduced when the disruption is less severe. But, ideally, according to Durach & Jose (2018), to tailor the inventory stockpile level to the risk size is a right way of ensuring that the issues of temptation and opportunity are dealt with to make the strategy more effective. Literature by Rotaru et al. (2014) indicates that implementing an adaptive inventory management strategy requires some capabilities, which were also identified by the respondents in the current study. For instance, the company has to establish an ongoing threat detection system that ensures that any potential disruptions are identified and distinguished according to their severity levels. It is therefore apparent that the adaptive risk management strategy is suitable when the associated risk occurs overtime, and when the company can detect this risk early enough. Furthermore, Zsidisin & Henke (2019) remark that the adaptive strategy is most effective in cases of internal disruptions such as labour unrest. Apart from a continuous threat detection system, the company must have the capacity to respond to the increased risk level as rapid as possible by building up the necessary stockpile level (Desai et al., 2015). Failure to have a quick response to the increased risk level would make the adaptive strategy less effective. The strategy of supply diversification has also been captured both in the current study and in the existing literature. According to the results of the current study, respondent mentioned that they use more than one supplier to cover for the risk of disruption, while others have suggested that they use more than one supply point to cover for any interruptions in case one supply point is interrupted. Existing literature also highlights how managers have used this strategy to mitigate supply chain risk, although many challenges characterize its application. According to Rotaru et al. (2014), the supply chain diversification strategy is mostly applied in companies with manufacturing or production facilities in different locations. Production is split (or supplies is sourced) from different production points (or suppliers) to partially protect the company from disruptions on one portion of the production facility or supplier especially if the interruption is on one supplier of one part of the facility (Kwak et al., 2018). With this regard, Durach & Jose (2018) postulate that the supply diversification strategy works best when the alternative supplier or production facility is capable of meeting the required capacity of production, as soon as possible. Nonetheless, establishing a diversity of supply is accompanied by various challenges. The respondents in the current study mentioned that they incur high costs in qualifying more than one supplier. Besides, the respondents noted that it is expensive to establish and maintain more than one warehouse. Similar observations were made by Zsidisin & Henke, (2019), who wrote that companies can incur high costs each time a new supply facility is built, or when there needs to maintain more than one supplier. Similarly, Rotaru et al. (2014) said that in an attempt to manage disruption risks by establishing supply points in different geographical locations, companies incur high costs to build and maintain them. Consequently, the economies of scales achieved through a wider geographic area of operation are offset by the costs of operating the facilities. Zsidisin & Henke, (2019), on the topic of supply chain diversification, says that the company has to strike a balance between having one facility of the supplier and having more than one supplier or facility that deals with different products. However, considering the costs associated with diversification, most companies would not want to stay in either of the extreme ends, but rather maintain a balance of expenses and risks.

Similar to the findings of the current study, literature by Durach & Jose (2018) also points out challenges related to correlation, when implementing the strategy of supply diversification. The author first explains that ideally, supply diversification strategy works under the assumption that when there is a disruption in one facility or with one supplier, the other facility or supplier meets the supply needs. However, an increased probability of one supplier or facility being disrupted increases the likelihood of the strategy’s failure. In a nutshell, disruption of both facilities and suppliers leads to a complete breakdown of the strategy. According to Samira et al. (2018), this implies that the effectiveness of supply diversification strategy is dependent on how the company can minimize events that might cause a joint disruption of both facilities of suppliers. The respondents in the current study noted that diversified supply chain is associated with a challenge of standardization and quality consistency. These results corroborate with the records of existing literature. For instance, according to Zsidisin & Henke, (2019), companies applying the diversification strategy are keen on their inconsistency tolerance and how they measure the quality and standards of the supplies. Whereas one organization may accept certain levels of inconsistencies, others may require the same qualities or identical features. Nonetheless, ascertaining any level of consistencies may be a challenge to supply managers, and this might even be costly for those dealing with sensitive products such as food and drugs. However, diversification emerges as an effective strategy for mitigating disruption risks despite its side effects. In simple terms, diversification is good but has various complexities and cost challenges. This implies that managers have to make crucial decisions regarding how to diversify, a process that might be time-consuming to undertake or undo. It is, therefore, necessary for managers to invest their time and effort when making decisions n diversification strategies. Apart from the supply diversification, results analysis also indicates the existence standby strategy as one of the strategies used by managers to respond to the risk of supply disruptions. As opposed to the supply diversification whereby the managers have to make advance investments in alternative facilities or suppliers, and where the company absorbs the costs associated with the strategy; the standby strategy does not involve any prior expenses incurred by the company, but rather, the disruptions are managed as and when they occur, using a non-routine alternative facility or supplier. In short, managers who use the standby strategy seek for an alternative facility or supplier that is not primarily part of the normal operations (Desai et al., 2015). As highlighted by the respondents, a typical example of the standby strategy is when employees are asked to supply gods with their vehicles when all the company trucks have broken down. This implies that the company uses an alternative that would ordinarily not be used in normal circumstances. However, Samira et al. (2018) also acknowledge the existence of a combined standby/diversification strategy, whereby the supplier or facility that is hardly used to produce the supplies steps in to cover for the breakdown. However, the standby strategy is associated with various challenges, which were identified by both the respondents and existing literature. For instance, Rotaru et al. (2014) state that if all the sources or suppliers experience a breakdown, and then there will be no standby strategy for use. Nonetheless, the availability of standby inventory may depend on whether it is sought from within or outside the company’s network. The availability of standby inventory would be easier to achieve compared to a situation where the standby inventory has to be sourced outside the company’s network (Durach & Jose, 2018). However, as highlighted by the respondents, emergency alternatives are associated with high costs. To guarantee availability; the company has to spend more than they would pay under normal circumstances. This implies that managers have to strike a balance between the standby inventory strategy and the inventory diversification strategy to ensure that they gent the value of costs incurred in both strategies.

The study also revealed that while trying to implement the standby inventory strategy, managers may encounter the challenge of capacity and response time of the emergency solution. Similar remarks are made by Rotaru et al. (2014) who observe that sometimes the standby inventory may not meet the capacity required to address the disruption, or may respond late. The two scenarios may render the strategy ineffective. The ultimate strategy that emerged for the data analysis is that of demand management. The respondents stated that they sometimes rely on managing the demand side to address supply disruptions. This strategy came out as manifest in the results section as it did in the literature by Samira et al. (2018), who noted rationing as one of the effective strategies that can be used to manage supply disruption risks. Samira et al. (2018) also identify switching as an effective strategy, whereby consumers are advised to switch to an alternative product in case the original product or supply is disrupted. Furthermore, the challenges highlighted by the respondents corroborate with those identified by existing literature. For instance, just as one of the respondents noted the problem of communication, Durach & Jose (2018) argued that it might be difficult to effectively execute the strategies of switching and rationing if the manager fails to implement a proper communication channel with the consumers, and this may threaten customer loyalty. These findings imply that the demand management strategy can only be successful if the manager maintains proper communication with the service recipient. Besides, according to Rotaru et al. (2014), managers need to put in place effective planning to ensure that the implementation runs smoothly.

5.2 Conclusion

While this study has identified various strategies for managing supply chain risks and disruptions, we recommend that managers should take note that each strategy has its advantages and disadvantages and applies within different circumstances. Besides, we recommend that managers should tailor the disruption management strategy to the specific circumstances surrounding the interruptions. It is also advisable to employ different strategies at once, especially when they want to achieve effective management of disruptions. We also advise that where possible managers should not separate the demand related risk from the supply-related risk when developing the risk management strategies. Instead, they should consider both types of risks and integrate the strategy to achieve effective outcomes. Last but not least, research in the area of supply risk management is at its infancy stage, evidenced by a lack of academic research in the field of practice. This study, therefore recommends further research with a broader sample population to develop more accurate knowledge.

References

Zsidisin, G. A., & Ritchie, B. (2008). Supply chain risk: A handbook of assessment, management, and performance. New York: Springer.

Khan, O., & Zsidisin, G. A. (2011). Handbook for supply chain risk management: Case studies, effective practices, and emerging trends. Ft. Lauderdale, FL: J. Ross Pub.

Olson, D. (2012). Supply Chain Risk Management: Tools for Analysis. New York Business Expert Press 2012

Zsidisin, G. A., & In Henke, M. (2019). Revisiting supply chain risk. Cham, Switzerland : Palgrave Macmillan, [2019] ©2019

Sodhi, M. M. S., & Tang, C. S. (2012). Managing supply chain risk. New York: Springer

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts