Teaching for Learner Agency

- 64 Pages

- Published On: 27-05-2024

Chapter One: Introduction

1.1 Statement of the problem

The understanding of the learner agency involves understanding the personal belief system and the circumstances that may impact their learning activities. This may present a complex interaction of factors, as Teng (2018) states, such as political and social development, cognitive psychology, sociolinguistics, metacognition and motivation. This may require teaching strategies to promote learner agency within the classroom. Thus, Mercer (2012) argues that before learners engage their resources and exercise their agency in a learning context, they are required to develop a personal sense of agency. She states that the learners should believe that their actions or behaviour can make a difference to their learning.

Literatures including that of (Lantolf & Thorne, 2006); (Little & Erickson, 2015); (Teng, 2018); (Benson, 2001); (Larsen-Freeman, 2019); and (Cross, 2009) all suggest diverse aspects of the notion of learner agency. On one hand, learner agency is defined in terms of learner centeredness and autonomy ( (Benson, 2001; Layder, 1993). While on the other hand, learner agency is perceived non-agentive that considers less of learner autonomy (Larsen-Freeman, 2019; Little & Erickson, 2015). Literatures, including (Teng, 2018; Little & Erickson, 2015; Cross, 2009), suggest that learner agency is a complex concept encompassing diverse perspective. It involves an interaction of political, social and cultural factors, individual elements including cognitive behaviour, socio-cultural factors, and other such internal and external factors that share learners’ action and intention. In the midst of these interaction, the role of the teachers impact the development of learner agency where they may cause stimulation or the opposite result in terms of learners’ capacity and development of agency (Little, et al., 2017).

The notion of learner agency comprises a complex interaction of multiple variables that can impact or shape the outcome of learning and teaching. Literatures, including (Teng, 2018; Mercer, 2012; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006; Little, et al., 2017), argue that the multiple variables such as identity, culture and social background can influence or impact learner agency’s understanding from the perspectives of participation, control, and resistance. They argue that learner agency is a complex notion given that all factors interact continuously shape the nature of the agency. The role of agency and the complex interaction also applies to learning and teaching English language. Gao (2010) argues that the learners of English should be empowered in term of socio-cultural and micro-political capacity, and motives and belief. Gao argues that agency values the strategy, educational investment and a broader life pursuits that the learners attached to while learning a language. The learners prioritise their power, will and capacity to act as a precondition to learner agency (Gao, 2010).

English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) is an umbrella term governing many forms of English language learning. The UK uses English as an additional language (EAL) primarily for younger learners in compulsory education and ESOL for adult and community learning (Marshall, 2015). This research has, however, considered ESOL in the context of English language teaching as a second language and as a foreign language. This research has not distinguished between English as a second language and English as a foreign language contexts. It has used ESOL to represent the entire field of teaching English to speakers of other languages. Based on the context, this research will explore the notion of learner agency and its impact of teaching and learning ESOL without differentiation the different forms of learning English or the learners’ age.

1.2. Context

A learner agency is constructed upon a complex dynamic interaction of different components involving multiple levels of learning context. Mercer (2012) employed a complexity theory to examine how she employed a single case study comprising a tertiary-level EFL learner. She found that the learner agency is situated ‘contextually, interpersonally, temporally and intrapersonally’. Thus, she states that learner agency should be understood from a holistic perspective. She also examined the learner’ belief system and stated that understanding the learner agency involves understanding of the complex components, involving their self-belief, belief about context, and belief about language learning and their mindsets (Mercer, 2012).

It is pertinent to note that learner agency is a complex system involving a range of components. Lantolf and Thorne (2006) stated that learning a language involves the action and intention on the part of the learner. According to Little, Dam, and Legenhausen (2017), learner agency involves both the individual and a collective capacity, and the role of the teachers is to stimulate the learners’ pre-existing capacity and harness their development of agency through a social-interactive process in the classrooms (Little, et al., 2017). This is a complex dynamic.

Teng (2018) stated that the inherent complexity in learner agency may present a major challenge in initiating the required agency behaviour in the learners. The complexity also may not make it possible for learners to take initiatives for every learning context and purpose. Thus, it may present the problem of defining the agency given the complex set of multiple components, which may make it difficult to understand the relationship between the learners, both individually and collectively (Teng, 2018).

1.3. Aims of the study

This research will primarily aim to define learner agency from multiple perspectives. This will include understanding those perspectives and the relation between learner agency and English Language Teaching (ELT). This research will elaborate and analyse how the concept of agency functions in an English Language classroom and explore application practices in an English for Speakers of Other Language (ESOL) environment.

1.4. Research question

This research will explore the teaching strategies that aim to promote learner agency within the ELT classroom; the influence of other disciplines on the approaches to learner agency in ELT; and a critical analysis of the learner agency approach in ELT. Accordingly, the main research question is as follows:

1. What is the extent of impact of learner agency on the effectiveness of the English Language Teaching classroom?

While exploring this main question, this research will explore the advantages and limitations of a learner agency approach in ELT.

1.5 Chapterisation

This research has the following chapterisation:

Chapter One – This chapter introduces the study including the aims and the research questions.

Chapter Two – This chapter offer a discussion of agency from a multi-dynamic perspective. It will discuss the non-agentive and the agentive perspective, including the elements of learners autonomy, self-regulation, and external elements in the form of social and cultural aspects in relation to learner agency.

Chapter Three – This chapter will discuss the research methodology employed in this research. It will discuss the research philosophy in the form of critical realism; the inductive approach; and the qualitative research approach including a systematic literature review adopted in this research to explore the research questions.

Chapter Four – This chapter will discuss the findings of the literature review in relevance to the research questions. This chapter will identify the main themes that will be found in this research.

Chapter Five – This chapter will conclude this research with a summary of the findings, limitations of the study, and recommendations for practice.

Chapter Two - Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

This chapter aims to discuss the meaning of learner agency from a multidisciplinary perspective to situate it later within the field of English language teaching. This chapter will explore the multi-dimensional aspect of learner agency. It will explore the use of learner agency in the learning and teaching of ESOL. While doing so, it will critically analyse the extent of effectiveness and the impact that learner agency has of ELT.

Learner agency is multi-dimensional as it involves aspects of psychology and sociology. Code (2020) presents learner agency as the inherent ability to ‘regulate, control, and monitor their own learning’. Agency signifies the effectiveness in regulating the cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes while the learners interacts within the learning environment. Thus, Code argues that learner agency is an intentional, self-generated and reactive capacity in the context of social factors. It is bound to four dimensions of agentic functioning, which are intentionality comprising the capacity to plan and decision; forethought comprising the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation; self-regulation; and self-efficacy (Code, 2020).

This chapter will the explore the various aspects and components that define learner agency. It will explore the impact of these components on the learning and teaching process with particular regard to ELT. While doing so, it will identify and analyse the teaching strategies that could effectively use learner agency within the ELT classroom and simultaneously identify the limitation of learner agency.

2.2 Non-agentive perception

In language learning and teaching, agency has been constructed as a form of motivation and intelligence. There are two major developments that elaborated the learner agency (Teng, 2018, p. 65). Firstly, as Benson (2001) stated, agency is the concept associated with learner centeredness and autonomy, which stresses upon the role of the learner as the active agent in learning a foreign language. Teng (2018) argues that learner autonomy is a multi-encompassing term as it can be seen from a different perspective, mainly political and social development, cognitive psychology, sociolinguistics, metacognition and motivation.

The teaching of English as a foreign language is based on a long term development of autonomy involving experiences accumulated over time inside and outside the class. The approach centred around learners is chosen as the alternative to the conventional method of teacher-led classroom (Teng, 2018). Learner autonomy is related to the capability of independent learning while the concept of agency is the conscious initiative in learning undertaken by the learner. Such a concept has been central to language education. This concept of agency is particularly important when it comes to enhancing the autonomous learning of the learners (Teng, 2018).

Secondly, as Lantolf and Pavlenko (2001: 145) stated, it is the increasing recognition of the interactive process between the learner and the learning contexts and the learner is the agent who is actively engaged in constructing the terms and conditions of their own learning. Thus, as Teng (2018) stated, learner agency indicates a self-directed learning focusing on the essential requirement that learners must foster a sense of agency to make optimal use of the learning opportunities (Teng, 2018, p. 66).

Educational researchers have defined agency as “the ability to exert control over and give direction to one's life” (Biesta & Tedder, 2007, p. 134). Miller and colleagues (2015) argues that that agency is fluid in time and space subject to alteration and change depending on time and situation. At the same time, there is continuity involved where the learners regard their life as an on-going narratives (Miller, et al., 2015). There are semi-permanent and repeated components as well as new relationships and situations and new opportunities for change. In connection with the understanding of language, learner agency may consist of recycled linguistic resources embedded with perspectives as well as a blend between the learners’ intention and the existing ideologies (Miller, et al., 2015). However, Larsen Freeman (2019) states that the language learners are also perceived to be non-agentive. She argues that a coordination dynamic could be a possible mechanism for the emergence of agency. According to her, CDST considers agency as temporary in terms of space and time that could be achieved or changed through iteration and co-adaptation. She stated that agency is multidimensional and heterarchical.

The Complex Dynamic Systems Theory (CDST) seeks to explain the use and development of language in terms of ‘complex, interconnected, dynamic, self-organising, context-dependent, open, adaptive and non-linear’ emergent systems (Larsen-Freeman, 2019). Freeman (2019) discussed CDST’s conceptualisation of agency where CDST maintains a structure–agency complementarity and at the same time brings forth the relational and emergent aspects of agency (Larsen-Freeman, 2019). Complex Dynamic Systems Theory (CDST) as a theory seeks to explain language use and development phenomena in terms of emergent systems that are complex, interconnected, dynamic, self-organizing, context-dependent, open, adaptive and non-linear (Larsen-Freeman, 2019). She cited seven perspectives (also deriving from content of works of others) to demonstrate that learners are non-agentive. Firstly, agency is developmental seen as a result of a systematic developmental sequence that all learners follow. Secondly, as Coughlan and Duff (1994) stated, agency is pedagogical where learners require comprehensible input in regards or their performance of task. Thirdly, as Duff and Doherty (2014) stated, agency is social where young learners are passively socialised into their communities. Fourthly, agency is categorical that indicates that learners can be categorised, which may change the manner of interaction with them and of how they think of themselves (Larsen-Freeman, 2019). Fifthly, based on what Molenaar (2008) and van Geert (2011) stated, agency is statistical where events and experiences of individuals could be captured by aggregating relevant data. Sixthly, agency is a closed system focussed on the purpose rather than the cause that promotes deficit thinking. This is based on arguments, including that of Han (2004), that suggest that there is no more constructive learning irrespective of the input, adequate motivation and opportunity for communicative practice. Seventhly, agency is ideological indicating that it does not accept the language or dialect of a minority (Larsen-Freeman, 2019). This indicates standardisation and monolingualism that may not consider the linguistic and identity practices of multilingual students (Farr & Song, 2011).

The non-agentive view gives an assumption that learning a language is institutional and instructional involving less of learners autonomy. Little and Erickson (2015) have termed education as a process of “people shaping” to help learners enhance and modify their identity while developing their agency. They cited the approach adopted by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR) in regard to language proficiency to state the central importance given to learner's identity and agency in the European Language Portfolio (ELP). While they reviewed the current trends regarding language assessment and their impact on learner identity and agency, they found the need to increase engagement of learner agency in the assessment processes (Little & Erickson, 2015). Reviewing the above argument and the non-agentive argument of Larsen-Freeman (2019), it may imply that the institutional and instructional aspects of language learning do not give enough room for development of learner agency.

2.4 Agentive perspective

Learner agency plays a crucial role in self-regulated learning. Xiao (2013) used the reflective narratives of a distance learner of English in China to investigate the manner in which learner agency mediates the learning. Xiao found that learner agency thus have a major impact on the self-efficacy, identity, motivation, and metacognition of the learner. These four elements determine the success of the learning, particular in the distance learning mode. Xiao (2014) found that there is a mutual enhancement cycle between the four elements and agentic engagement.

Learning experiences are assimilated into one’s concept of self and development of self (Irie & Brewster, 2014). Bandura (1997, 1986) demonstrated that the way an individual reflects on their experiences and actions in regard to their actions and plan determines their success or failure and their future self-image. This concept of self-efficacy is important in understanding learning from the context of self-efficacy. Irie and Brewster (2014) studied two English learners with the same skill and found that one learner maintained the motivation to become a competent English user and could regulate their own English language studies while the second struggled. They cited the Schunk (1989), who argues that self-efficacy presents a strong predicator of one’s likelihood to succeed. Bandura (1994: 2) describes self-efficacy as the ‘belief in ones’ capabilities to organise and execute the courses of actions required to manage prospective situations’. In terms of English learning, Raoofi and his colleagues (2012) reviewed 32 studies between 2003 and 2012 regarding self-efficacy and found that these studies reinforce that self-efficacy as a learner variable can be a key factor influencing learners’ proceed with their language learning experiences (Raoofi, et al., 2012). Thus, the better agents are those who accommodate themselves in an activity and they have more likelihood of progress (Lantolf & Pavlenko, 2001, p. 145).

Agency links motivation and actions and hence is constantly shaped and reshaped (Lantolf & Pavlenko, 2001, p. 145). Lantolf and Genung (2002) studied the fluctuating nature of motives in L2 learning in the social and cultural contexts by analysing the narratives of an enthusiastic graduate student attempt to learn Chinese as an additional language. They observed that the student started out highly motivated and as an effective language learner. They found her motive gradually changed when most of the language teaching programme was spent on grammatical pattern drills. She ended up being unhappy and unaccomplished learner. Her motive shifted to merely fulfilling the language requirements (Lantolf & Genung, 2002). Zimmerman (2001) argued that learners are self-regulated to the extent they are “metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally active participants in their own learning processes” (Zimmerman, 2001). In another context, learners were found more motivated outside of school. Sturtevant and Kim (2009) examined the literacy motivation amongst 8 middle-school students in ESOL classes. They found that the beginning ESOL group exhibited higher motivation than the more advanced groups in the aspect of “valuing” of reading. However, all of them reported a strong interest in reading and writing, especially outside of school. They found a wide range of literacy activities in the families where the students were both learners and teachers (Sturtevant & Kim, 2009).

Self-regulated learning involves “self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions in order to attain educational goals that include such processes as planning and managing time; attending to and concentrating on instruction; organizing, rehearsing, and coding information; establishing a productive work environment; and using social resources effectively” (McInerney, 2008, p. 374). Such a learner knows their strengths and weaknesses, and adapts to different learning situations and learning strategies (Hartley & Bendixen, 2001). Thus, it involves an active and constructive process where learning goals are set against which attempt to achieve, monitor, regulate or control are made by the learner (Pintrich, 2000). Self-regulation involves a conscious awareness where appropriate strategies are selected and deployed to achieve learning goals (Jain & Dowson, 2009; Jansen, et al., 2019).

2.5 Curriculum and Assessment

Agency is understood as the ‘capacity to act independently and to make one’s own choices’ Education curricula have a development role in learner agency (Manyukhina & Wyse, 2019). Manyukhina and Wyse (2019) stated that the potential implications of curriculum for learner agency are underexplored. They reviewed the national curriculum documents of England, Australia, Hong-Kong, and Canada. They identified three types of curricula: knowledge-based, skills-oriented and learner-centred. Based on their review, they recommended that the learner agency should be a key orientation of any national curriculum (Manyukhina & Wyse, 2019). Similar view is reiterated by Raffo and his colleagues (2021) who mention that learner agency plays the key role in understanding the young people's engagement with the curriculum. They state that while understanding the learner agency and their associated external and internal factors, the thought process has been guided by theories derived from traditional aspects of sociology, philosophy and psychology (Raffo, et al., 2021). This traditional approach replaces the subjects (learner) and objects (curriculum) of learner agency by the curriculum experiences of the learners as a part of their learning and wider life. Thus, the traditional approach sees only events rather than substances (Raffo, et al., 2021). In this context, curriculum may be strictly seen as stating what it ought to do and what the aims with less consideration to what it is that may fulfil the aims of the curriculum. Thus, Young (2014) argues that curricula are social fact. It cannot be reduce to acts, beliefs or motivation of individuals. Thus, it structurally constraints the activities of the teachers, students and those who design it (Young, 2014). At the same time, curricula makes it possible for some to learn that may be found impossible by some, or sets limits to learn what is possible. Thus, curriculum have specific purposes. A curriculum can be traditionally seen as the only mechanism of transmitting knowledge or a proven mechanism that has delivered learning result. At the same time, it cannot be taken as a particular mode of pedagogy. It vary based on the varying capabilities of the learners (Young, 2014). There is a relational perspective to the subject and the objects where the activities of the learners cannot be understood in isolation, but rather in the context of their surrounding environment. There is a continuous experience that has a structural influence on the curriculum experiences (Raffo, et al., 2021). Hence, education curricula is central to learning and development where it should be contextual, interpersonal, intra-personal and temporal that focuses on the educational reflexivity and associated learner agency of the learner situated curriculum enabling the learner to mediate educational lives (Raffo, et al., 2021).

Curriculum should have a pragmatic approach enabling learners to fulfil their lives expectation and goals. For example, one of the items that the English learning programme or curriculum could promote is that of the practice of listening logs for extensive listening in a self-regulated environment. (Lee & Cha, 2017) examined how learner journals, particularly listening logs impacted students’ listening proficiency and how they reported their listening activities.

The study covered 42 students taking an English listening practice course at a university. They kept a weekly listening log for one semester where they wrote their listening experience. To find the effects of the logs, the study conducted TOEFL tests as pre-and post-tests. They found that the writing listening logs regularly influenced their improved listening comprehension. It also positively impacted their motivation, built confidence and helped managed their learning.

Learner agency encompasses the concept of self-assessment, which is a core element of self-regulation (Blaschke, et al., 2021; Sullivan, 2014). Self-assessment involves ones’ awareness of the set goals and monitoring their progress. Self-assessment can enhance self-regulation as well as one’s achievement (Schunk, 2003). The process of self-assessment is formative in nature. It is no longer the traditional normative practices that endorsed the understandings of intelligence as fixed and that of failure as not acceptable (Sullivan, 2014). This traditional assessment may constrain learning and would restrict learner from risk-taking (Wyatt-Smith, et al., 2014). In an instructional context, the normative assessment may not deliver a constructive result. Learners should be enabled to make their choices and as such new ways may be developed to capture their learning skills, competence and dispositions (Wyatt-Smith, et al., 2014).

The modern form of assessment is more towards a learner-centered space. Sweet and her colleagues (2019) argue that this has shifted the focus from traditional teacher as the center of knowledge and the only one who evaluates. They proposed the Basic Outcomes Student Self-Assessment (BOSSA) model, which they consider as a ‘fully integrated standardised second language self-assessment protocol’ that could be operated on a large scale. They validated this model piloting over semesters and putting self-assessment into operation at the University of Minnesota covering 10,000 students in ten languages. They found that a self-assessment protocol along with a proximal performance opportunity, training, and practice can support learners, instructors and language programmes successfully. They suggest that this model could address the demands for an integrating research-driven practice and transdisciplinary approaches, which are the essential elements of second language teaching and learning (Sweet, et al., 2019).

In self-assessment, learners reflect on the work quality, judge the degree of their work quality in relation to their set goals, and revise accordingly. Roever and Powers (2005) argue that self-assessments of English language skills are useful in various settings. They examined the effect of self-assessment of English language skills in English against the self-assessor’s native language, by covering 115 volunteers at test sites in Mexico, Germany, Taiwan and Korea. They found comparable responses in both the languages regarding reliability, level and variation. They, however, highlighted one limitation that the meaning of the responses may differ based on the language on which the assessment is administered (Roever & Powers, 2005). Andrade and Valtcheva (2009) set out three steps in self-assessment: articulate expectations, self-assessment and revision. This is a formative assessment done on work drafts that are progress to inform revision and improvement rather than determining their own grades. (Andrade & Valtcheva, 2009). Accordingly, the assessment should follow an articulate expectation for the task set by the learner or the teacher or both. This way the learners are better acquainted with their tasks in terms of priority elements and determining quality (Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006). The next step is self-assessment where students monitor the progress of the work drafts in progress by comparing their performances against the articulated expectations (Andrade, et al., 2008). The third step is for the students to use the feedback from self-assessments to guide revision. This last step will ensure that their efforts could led to opportunities of improvements and increasing their grades (Andrade & Valtcheva, 2009).

2.6. Socio-cultural oriented agency

From a CDST perspective, the use, development and acquisition is an intricate and complex dynamic process. This is supported by studies conducted by (Larsen-Freeman, 2006; Verspoor, et al., 2008; Spoelman & Verspoor, 2010) that explored learners’ writing development including vocabulary development (Zheng & Feng, 2017); strategy use and listening performance (Dong, 2016); learner agency (Mercer, 2011), and English speech (Polat & Kim, 2014). Larsen-Freeman and Cameron (2008) state that all these studies have argued that language learning comprises interconnecting and self-organising systems that co-adapt or show emergence of new modes and behaviours. Thus, Cross (2009: 31) appropriately stated that “Agency exists in the dialectic between social structures created through cultural-historical tools (policy) and the [ontogenetic] subject”. Cross argued that although the subject is not entirely ‘free’, each of them bring their ontogeneity to the learning process that acts an enacter of the learning policy at the microgenetic level (Cross, 2009, p. 32). This process indicates the manner in which the learners act as the agents.

Learning a new language is a process of socialisation for both children and adults. There is an involvement of reproduction of cultural norms through the influence of the parents and a negotiation of the norms and practices. This is a language socialisation processes that involve conflict, negotiation and failure (Fogle, 2012). As Duff (2012) stated, this process may produce both the outcome of achievement and acculturation as well as defiant, resistant or ambivalent attitudes or rejection of target language, premature termination or suspension of learning. Fogle (2012), thus, stated that all these processes are connected with learner agency. Thus, the concepts of agency, negotiation and conflict are key constructs relevant with the understanding of language learning and socialisation.

The language learning process has the cultural and ideological underpinnings. There is a language socialisation paradigm where the family and classroom settings are interconnected (Fogle, 2012). Such a paradigm comprises two sets of socialisation processes. First is the traditionally process that focuses on the reproduction of cultural norms through and into the linguistic practices. This process emphasises on the influential role of the parents’ beliefs and ideologies in regard to the language learning (Fogle, 2012). The second process focuses on understanding the manner of negotiations regarding norms and practices and the contradiction in identities and productions of the learners (Fogle, 2012). The former process is unidirectional. The latter is bidirectional process that allows the understanding of both the cultural and linguistic changes (Fogle, 2012).

The orientation of curriculum, as Manyukhina and Wyse (2019) suggest, may also bring about a social justice oriented approach to developing learner agency. Hempel-Jorgensen (2015) argued that the capacity of disadvantaged learners to exercise learner agency is unequally constrained. She used a socio-cultural theory of learner agency to argue that although socially just pedagogies, including Critical and Productive Pedagogies aim to support learner agency, they are limited.

Hempel-Jorgensen argues that to reduce the constraint and improve the capacity, the learner agency can be extended from learning that focuses on making meaning and constructing knowledge to co-imagining socially just teaching and co-transforming existing unjust teaching practices (Hempel-Jorgensen, 2015). For example, children may be exposed to varying problems. In this respect, as Paradis (2011) argues, depending on their needs, teachers may develop appropriate strategies for the development of their vocabulary. Such strategies may require greater exploration of their problems in acquiring vocabulary (Paradis, 2011).

The learning plan can be formulated treating children as agents. Mannion (2017), thus, argued that young people could be treated as agents in themselves and as participants in the decision-making process by allowing them to voice opinions and share experiences (Mannion, 2007). The suggestion of Harcourt and Einarsdottir (2011) support this argument when they stated that in order for children to participate in decision making, they should be investigated in their own right, for example, the study conducted by Harcourt (2011) that involved children between six years to eight years of age asking them their opinions. Harcourt (2011) identified the presence of children and their accounts of life as one of the essential elements to understanding their social worlds.

The socio-cultural context of the learners also play certain influences on learner agency. Sullivan and McCarthy (2004) argue that a socio-cultural view of agency can suit the study of how learners make use of their cultural resources, as a means of mediation or to gain power in the community. This cultural perspective involves the cultural systems and activities rather than the individuals. It focuses less on understanding personal stories, which may exclude the emotional and affective aspects of the agentive experience (Sullivan & McCarthy, 2004). At the same time, Miller and colleagues (2015) stated that a dialogical perspective of agency that focuses on individuals may enable them to highlight the feeling, living and expressive experiences of the individuals. Together with these personal perspectives, their feelings and emotions may also play an important part in the agentive experience (Miller, et al., 2015).

Learner agency is exposed to diverse internal and external perspectives of the learners. Markova and Foppa (1991) argues that agency is a relational phenomenon, which considers a range of ideological discourses based on the personal, cultural and other external perspectives. Individuals are opened to opportunities to choose and decline viewpoints and ideological contents of others (Bakhtin, 1981). Such opportunities should be provided. For instance, Wardman (2012) conducted a qualitative inquiry in the North of England to analyse the practice in UK primary schools regarding language teaching. She found that although the UK is multicultural, it is monolingual regarding the language of instruction in schools. Accordingly, she stated that even when the L1 (native language) is used for instructional purposes, it must be transitional with the focus on assimilating the children into L2 (the English language) effectively and quickly (Wardman, 2012). The views of Schneider and Davies-Tutt (2014) also support this argument. They stated that encouragement by teachers to write in L1 helped the students in feeling welcome and included. Since Learning English is considered essential for the socialising, English as an Additional Language (EAL) students are encouraged to speak English quickly (Schneider & Davies-Tutt, 2014).

2.7. Learner’s Personal engagement

Learner Agency emerges in a dialogic interplay comprising power relations and other asymmetries such as native or non-native speakers or students and teachers. Miller and colleagues (2015) argue that language learners observe and learn words from their family, teachers, peers and other mediums or media such as textbooks and popular cultures. Reinders and Lazaro (2011) argued that learners are engaged in a highly personal, variable and contextually influenced process. In this regard, teachers’ efforts involve understanding the experiences of the learners. For instance, they stated that teachers working in self-access centres find themselves with the need to employ an additional or different skill-set than those used in a classroom. In such centres, tasks are carried out by the learners themselves, such as identifying the learning needs, goal setting, monitoring progress and selecting materials with or without teachers (Reinders & Lazaro, 2011). Facilitators provide individualised help in case of needs that have great flexibility. They often find a diverse range of interests and needs (Moore & Reindeer, 2003).

Spolsky (2004: 7) stated that ecology is an useful metaphor regarding language policy and planning. Spolsky emphasised the value of examining language from the perspective of a complex cultural system that involves both linguistic and non-linguistic variables. Haugen (1971: 20) defined the ecology of language as “the study of the interactions between any given language and its environment”. Thus, the linguistic ecology is essential to approach in understanding the roles of language teacher agency with respect to the language policy and planning. This approach will cover a wider range of factors and agentive perspectives. However, there are others, such as Johnson (2013) and Pennycook (2004) who have a critical outlook towards linguistic ecology. Johnson cautioned that while linguistic ecology may bring certain value to the study of language, there may be questions of its value or appropriateness. This is supported Pennycook (2004) who argued that the approach can lead to ‘objectification’, ‘enumeration’ and ‘biologisation’ of languages. This means it can essentialise language, which the approach of linguistic ecology aims to challenge. He argued that it might render languages to be natural objects rather than cultural artefacts.

The manner a learner behaves in terms of how they approach learning could be analysed from a psychological perspective. Williams, Mercer and Ryan (2016) stated that according to the behavioural approach, learning is explained in terms of conditions. They cited B.F Skinner’s, Consensus and Contribution (1987), who applied this approach to learning with relation to response to stimuli. Skinner argued that if the behaviour is reinforced, for example either by reward or punishment, it may determine the likelihood of an increase or decrease in the occurrence of the behaviour. This means that any kind of behaviour could be reinforced. Skinner gave the example of instructional reinforcement, including tasks broken down into smaller and sequential steps and learning programmes with positive reinforcement at every stage (Williams, et al., 2016).

Williams, Mercer and Ryan (2016) stated that the behaviourists’ views have seen positive influence on language teaching methods. However, they are also not free from limitation. They further stated that learners may correctly respond to stimuli, but may not cognitively engage in the activity. This means that they are not using analytical skillset or engagement pertaining to the language learning. They may not focus on the meaning of the language as the focus is more on performing the tasks. Hence, there is less interaction or negotiation (Williams, et al., 2016).

This behavioural approach is unlike the cognitive approach in learning that involves encouraging learners to use analytical mindset, to hypothesise and deduce and to be actively interactive. Thus, a learner will employ such strategies including analysing, seeking or identifying patterns, formulating rules and experimenting with the language (Williams, et al., 2016).

Extending the cognitive approach is the constructivism that explains how a person makes a personal sense of their world (Williams, et al., 2016). Accordingly, individuals are in an on-going construction of their own understanding of their experiences. Their senses are unique (Williams, et al., 2016). Piaget (1966, 1974) stated that an individual goes through the sensory-motor stage of learning where they think and learn and explore the world through basic senses. They go through a formal operational thinking where they use abstract reasoning to develop their understanding of the world. This is relevant with the language learners who are actively making sense of the language. They then through assimilation where they try to fit their new found information in their existing knowledge base and may modify this input through the process of accommodation (Piaget, 1996; Piaget, 1974). Thus, people are always going through a personal construction of the world through the process of hypothesis, testing and drawing conclusions and developing a personal understanding or theories regarding the surrounding environment (Kelly, 1955).

2.8. Conclusion

Learner agency has both the psychological and social aspects. It is temporal in nature where the current surrounding environment of the learner influences the learning and learning capacity and manner of learning. Thus, the learning conditions, interaction and experiences shape the effectiveness of learner agency. The non-agentive and agentic development will influence the learner’s orientation, practice and outcomes.

Chapter Three - Research Methods

Research is a systematic process as determined by the researcher based on the research aims, objectives and questions (Saunders, et al., 2021). It involves methods to inquire into the specified questions that are the subject matter of the research (Kothari, 2004). It is therefore methodological where the researcher formulates the research methodology including the structure and design (Saunders, et al., 2012). This chapter will discuss the research methodology employed by the researcher to explore the research questions.

3.1. Overview

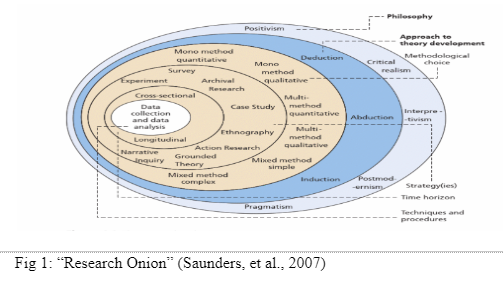

In this research study, the researcher accessed a multiple number of information and data in books, journals, reports, and other databases. All of such information and data were not relevant to the research study. The use of a research methodology formulated by the researcher helped in identifying and using only those data and information that were relevant to the research subject matter and help answer the research questions. The researcher relied upon the “research onion” (given below) developed by (Saunders, et al., 2007) to formulate the methodology and design.

3.2. Philosophy

Social science researchers generally apply research philosophies, including Critical Realism, Interpretivism, Positivism, Constructivism, Objectivism, Pragmatism and Post Modernism. The philosophies shape the research designs. Realism involves a scientific practice where the researcher generally adopts an empirical and critical approaches (Bryman & Bell, 2015). The philosophy of Interpretivism encourages epistemological consideration of the researcher’s views (Saunders, et al., 2012). The philosophy of Positivism involves objectivism where the research applies scientific methods of enquiry (Easterby-Smith, et al., 2015). Constructivism signifies that the social actors create the phenomena (Creswell, 2014). Pragmatism relies on the practical consequences of the research (Creswell, 2014). Postmodernism uses concepts such as post-colonialism and capitalism as theoretical constructs to guide research approaches and to question social scientists who try to uncover an already existing social reality (Dickens & Fontana, 2015).

The philosophy used for this research is critical realism. Layder (1993: 16) stated that “a central feature of realism is its attempt to preserve a 'scientific' attitude towards social analysis at the same time as recognizing the importance of actors' meanings.” Critical realism helped provide a theoretical foundation for a more comprehensive view of the learner agency and provide a balanced approach towards promoting learner autonomy in ELT. In this regard, the research draws upon the existing literature including its content analysis and findings. This research explored the impact of learner agency on the effectiveness of the English Language Teaching classroom. By applying critical realism, it explored the agentive and non-agentive view of learner agency, the concept of learner centeredness and autonomy, and theories such as a complexity theory addressing self-directed learning (Teng, 2018; Benson, 2001; Mercer, 2012).

3.3. Theory development

Researchers generally adopt one of the three approaches to theory development. They are the inductive, deductive and abductive approaches (Opoku, et al., 2016). The inductive approach starts with observing phenomena before data collection and then the relevant theory is built. The process involves moving from the specific case or context to a general theory (Collis & Hussey, 2009). Unlike the inductive approach, the deductive approach starts from identifying a general theory and applying it to a specific case or context. Here, the researcher moves from general to specific when they identify the theory, formulate a hypothesis before collecting observations and confirm the theory (Collis & Hussey, 2009). In the abductive approach, the process moves from observation to theory but is cyclical where the researcher creates a dialogue between the theory, data and social context at every stage of the process (Opoku, et al., 2016).

For this research, the researcher has involved an inductive approach. This approach allowed the researcher to better understand the nature of the challenges that English Language Teaching faces in motivating learner agency and to formulate a theory in suggesting recommendation to improve the situation.

3.4. Research Methodology

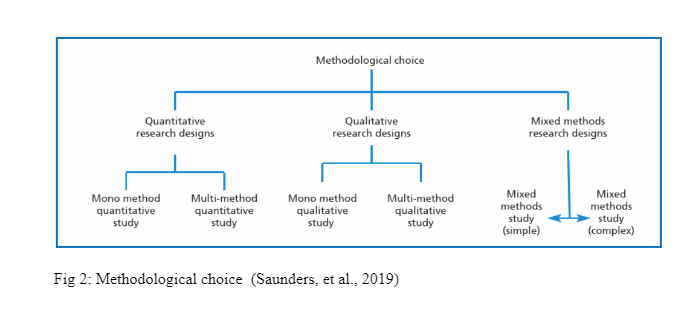

The researcher referred and formulated the methodology by referring to the model of methodological choices presented by (Saunders, et al., 2019).

Korpershoek et al. (2019), argued that Maslow's theory of motivation presumes that all the students experience the needs in the same order as mentioned in the theory, thus failing to identify the behavioural and cultural differences between the students of primary and secondary schools. The theory also does not explain quite accurately how self-actualized students actually feel and behave in the class.

2.4.4 ARCS Model of Motivation

Creswell (2014:12-14) also stated that research designs are of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (Creswell, 2014). Quantitative research examines relationships between variables that are measured numerically and analysed statistically (Creswell, 2014). This current research did not involve collective numerical data or statistically analysis. Therefore, the quantitative method was not applied. Similarly, this research did not use the mixed method as it involves the use of both qualitative and quantitative techniques for collecting data (Creswell, 2014).

This research has used the qualitative research approach, which involves multiple decisions regarding research designs and planning (Salmons, 2015). This method allowed the exploration of the research question from many diverse perspectives. This was necessary as each perspective could change the nature of the research and the findings, which eventually must fit in a larger design framework (Salmons, 2015). Thus, in this research, the primary research question is to explore the extent of impact of learner agency on the effectiveness of the English Language Teaching classroom. This involved an analysis and understanding of dynamic and complex range of components. The research had to undertake a socio-cultural view of agency (Sullivan and McCarthy, 2004) beyond the emotional and affective aspects of the agentive experience and otherwise a dialogical perspective of agency focusing on individuals’ feeling, living and expressive experiences (Miller and colleagues, 2015). Learner agency is thus a complex understanding of varied components. On one hand, the research analysed the agentive perspective focused on self-regulated learning and perspectives of self-efficacy, identity, and motivation (Xiao, 2013). On the other hand, the research focused on the non-agentive perspective that considers only the institutional and instructional language learning (Little and Erickson, 2015). In between, the research also analysed the concept of learner agency from both the individual and collective capacity with focus on teachers’ role (Dam, and Legenhausen, 2017) adopting a social-interactive process (Little, et al., 2017).

The qualitative method allowed an open and flexible approach for the researcher based which the most suitable research design was formulated for this research(Opoku, Ahmed, & Akotia, 2016, p. 35). As seen above, this flexible approach allowed the researched to review or explore the research question from a diverse range of perspectives (Creswell, 2013). Thus, while evaluating agentive perspective, this research analysed the factors and components that drove self-autonomy or self-direction toward English language learning. This research considered the sociological and cultural factors and inherent characteristics of the learners. Similarly, while analysing the non-agentive perspective, this research analysed the institutional factors, such as the curriculum or the teaching design including efforts and role of the teachers to motivate learners. These are the diverse variables analysed because they impacted learner agency and relevant strategic decisions and therefore, the research method allowed drawing relationships between the research variables (Creswell, 2013).

The research questions and objectives are raised in this research based on reviewing the historical developments until now regarding the Saudi-British relation. Certain trends in their relations are observed in the above sections. However, a qualitative research will enable reviewing the relations from different perspectives. As such, the observation made earlier about the constant trend in the relation could change on a further in-depth research. Thus, while formulating a research design around the research questions, it will ensure that the elements of this study must make sense together identifying relevant clear connecting links aligning each element. The research design will be made considering the context of the study (Salmons, 2015).

3.4. Strategy

This research has used the Grounded Theory to answer the research questions. This strategy involves the technique and procedure of data collection employed to develop theoretical explanations for social interactions. This theory is used in qualitative research, and it could be used with secondary data (Saunders, et al., 2019; Whiteside, et al., 2012). This research, thus, adopted the Grounded Theory to develop theories in order to explain learner agency from a critical realist point of view.

This research involved a systematic literature review that included collecting secondary data. This review process involved a scientific method of selecting literatures that provided relevant secondary data that could address the research question (Green, et al., 2011, p. 6).

The primary purpose of the literature review was to establish a rationale for this research and to demonstrate why the research question/aims/objectives are important. Thus, the literature review analysed the concept of learner agency, the importance of self-motivation and self-direction, and the impact of institutional directions and mechanism governing English learning and teaching among other things. The literature review also helped the researcher highlight the question of adequacy or sufficiency of the existing literature regarding the research subject matter with the objective of offering different or new perspective (Daymon & Holloway, 2010). Thus, the primary research question was framed to drive an analyse of the agentive or non-agentive view and their relevant factors with a view to enhance understanding of the subject matter (Daymon & Holloway, 2010). Based on this context, the researcher became familiarise with the subject matter of research and mitigated the risks of repeating existing research, including its strength and flaws (Daymon & Holloway, 2010).

The secondary data collection allowed the researcher to apply theoretical knowledge and use existing data to address the research questions. It allowed an inductive analysis of data using grounded theory methods of theoretical sampling and a critical realist approach to understand learner agency and developing relevant theories.

Since the research has adopted a qualitative method, the research work is descriptive in nature (Supino & Borer, 2012). Thus, this research has described about learner agency or factors that drive the effectiveness of learner agency, or the cognitive approach in learning. The nature of this research and its methodology thus involved a bottom-up approach (Bryman & Hardy, 2009). The secondary data collected is subjective and thus qualitative in nature (Jones, 2004). Therefore, this research followed a thematic analysis to organise and analyse the qualitative data (Bearman & Dawson, 2013). Major themes were created based on the core messages gathered from the data collected (Bearman & Dawson, 2013). For instance, the belief system of the learner is influenced by their life experiences and narratives, which in turn shapes the manner in which they exercise their autonomy and self-regulation. This also led another characterisation of their belief system that it is influenced by the learning environment, which includes the learning context, the socio-cultural aspects and their personal capacities. These themes also enabled understanding the role of the learning curriculum and self-assessment, which represents the behavioural aspect of the learner agency. These recurrent themes recognised by the researcher allowed producing meaningful and useful results (Attride-Stirking, 2001).

3.5. Data

This research adopted a desk-based research where secondary data were collected and analyse. The data included commentaries and opinions of scholars regarding the subject matter of research. Since the research was online based, the researcher used online platforms, including Google Books, Google Scholar and other similar online platforms. It allowed the research access to numerous data and information from multiple books, journals, reports and such materials. The online-based access allowed speedy review of the relevant books and articles.

Based on the research philosophy, methods and design, the research method adopted represents an intertwined socio-cultural, a psychological and institutional features of learner agency that provided a multi-faceted characterisation of learner agency in English Language Teaching.

Chapter Four - Findings and Discussion

4.1. Introduction

The literature review has explored the concept of learner agency from a multidisciplinary perspective in connection with ELT. In the context of the research question, this literature review explored the extent of impact of learner agency on the effectiveness of the English Language Teaching classroom. The literature review has found the learner agency cannot be understood in one dimension. It analysed various components of internal and external factors that are inter-linked and they interact in a dynamic fashion.

The literature review found that learner agency is multi-dimensional, involving varying components of psychology and sociology. Learner agency is understood as on intrinsic and inherent value system recognising the cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes. The concept of learner centeredness and autonomy are relevant here (Code, 2020; Benson, 2001). At the same time, the concept of learner autonomy cannot be understood without the political and social development perspectives. Hence, it is fluid and flexible enough to alter and change due to external factors (Miller, et al., 2015; Teng, 2018).

The literature review findings suggest that learner agency comprises both the non-agentive aspect and the agentive aspect. The former refers to the external factors that shape and influence learner agency or more particularly the purpose. Accordingly, learners require comprehensible input; is influenced by social interaction; and are categorisable that impacts their own perception and interaction with society. The latter aspect considers the elements of active, constructive learning based on motivation, opportunity and self-regulation. This aspect is indifferent to standardisation and is considerate to individualistic inherent capacities of the learners (Farr & Song, 2011; Larsen-Freeman, 2019).

The literature review findings suggest that learner agency is mostly the belief system of the learner developed and shaped by the continuous interaction of the self with the learning context including the institutional and instructional aspect of learning and the external social and politcal events and developments. Learner agency cannot be understood either from an agentive perspective or from a non-agentive perspective. This is to state that it cannot be understood by merely focusing on the learners’ individual characteristics such as autonomy and centredness, or by merely focussing on the surrounding circumstances. These two aspects are the main themes found in the literature review.

4.2. Life experiences and actions and autonomy and centredness

There is an interplay between the life experiences and actions and the learners’ autonomy and centredness. Bandura (1997, 1986) argued that a learner reflects on their life experiences and actions regarding their learning actions and plan further shaping the success or failure and their future self-image. The notion of centeredness and autonomy, as Benson (2001) argued, focuses on the role of the learner as the active agent in learning a foreign language. While being an active agent, learners adopt a self-direction approach, where, as Lantolf and Pavlenko (2001: 145) argued, there is an interaction between them and the learning contexts and the learners construct the terms and conditions of their own learning. The construction of the learning terms and conditions is a reflection of their own life experiences and actions. According to constructivism, learners make a personal sense of their world through a continuous going construction of their own understanding of their experiences and learn and explore the world through basic senses (Williams, et al., 2016; Piaget, 1966, 1974). The literature review, thus, pointed out that the language learners do the same construction to make sense of the language in order to assimilate and accommodate the new found information into their existing knowledge base (Piaget, 1996; Piaget, 1974). Thus, the reflection of the own life experiences and actions may be treated as a self-directed learning or the exercise of autonomy to foster a sense of agency regarding the learning opportunities. In regard to this finding, it is appropriate to cite Mercer (2012) who stated that learner agency is situated ‘contextually, interpersonally, temporally and intrapersonally’. There is a holistic perspective to learner agency, which is shaped by the learner’ belief system.

4.3. Learners’ belief system and the learning environment

The literature findings from the works of (Mercer, 2012; Little, Dam, & Legenhausen, 2017);( Williams, et al., 2016; Code, 2020);(Teng, 2018; Irie & Brewster, 2014; Bandura, 1997, 1986) suggest that the learning environment is extended from the learning context to the surrounding environment in which the learners dwell. It means it is not only inside the class or the learning context, but also outside the class or the social context that may shape the belief system. Thus, the belief system of the learners seems to be influenced by the learning environment, which covers both the classroom and outside the classroom factors.

Mercer (2012) highlighted the complex set up of learners’ self-belief, belief about context, and belief about language learning and their mindsets while understanding learner agency. The literature reviewed in this research has highlighted the complexity characteristics of learner agency, whether it is while discussing learner autonomy and centredness, the external institutional or instructional aspect and the belief system of the learners. According to Little, Dam, and Legenhausen (2017), the belief system is not just focused on the learners’ own individual capacity, but also the collective capacity that is represented by the institutional factors. There is a cognitive approach where learners use an analytical mindset, hypothesise, deduce and are actively interactive while formulating learning patterns and rules (Williams, et al., 2016). The patterns and rules formulated seem to form the characteristics of the learners’ belief system. This belief system facilitates the exercise of autonomy where they reflect on their experiences and capacity to learn and assimilate the experiences in the development of self (Teng, 2018; Irie & Brewster, 2014; Bandura, 1997, 1986). Thus, based on Code’s argument, it can be stated that the belief system is formed through an intentional, self-generated and reactive capacity of the learners considering the social factors. Thus, the planning, decision, motivation, self-regulation, and self-efficacy may evidence the influence as well as development of the belief system in regard to learner agency (Code, 2020).

The belief component in learner agency may be subject to flexible characteristics of learner agency. According to Miller and colleagues (2015), the fluidity in agency allows alteration and change considering the on-going narratives of learners’ life. This brings in the application of the behavioural approach to learner agency. The behavioural approach can explain the agentive and the non-agentive aspects of learner agency. B.F Skinner’s, Consensus and Contribution (1987) stated that a learning behaviour can be reinforced through instructional reinforcement (Williams, et al., 2016). This is supported by (Larsen-Freeman, 2019; Han, 2004; Molenaar, 2008; van Geert, 2011) who gave the non-agentive aspects to learner agency where learners can learn through inputs, systematic development, and socialisation. The learning can also be demonstrated through data-oriented learning based on events and experiences of individuals. Han (2004), thus, presents the parameter of learner agency to the extent of learning driven by the inputs, the systematic development and the social interaction. Beyond this extent, the learner employs their own agentive aspect to achieve learning objectives. This is demonstrated by the study findings of (Irie & Brewster, 2014; Raoofi & his colleagues, 2012). In the finding by (Irie & Brewster, 2014), one of the learners despite, have having the same skillset, could not be motivated to become a competent English user like the other learner who could regulate their own English language studies. (Raoofi, et al., 2012) found that self-efficacy can significantly influence learners’ learning experiences. These findings are relevant to the construct of learners’ belief system discussed earlier encompassing self-belief and belief in the learning and social environment. Thus, the literatures of (Schunk, 1989; Bandura, 1994; Lantolf & Pavlenko, 2001) present the primary importance that self-efficacy and the ability to accommodate with surrounding learning context both inside and outside the classrooms play key roles in determining the likelihood to succeed or progress.

The literature review suggests that the limitation of the non-agentive aspects in the form of standardisation and monolingualism may be addressed by the agentive aspect of learner agency, as discussed in the above paragraph. The literatures of (Xiao, 2013; Farr & Song, 2011; Little, et al., 2017; Teng, 2018) demonstrate this aspect. Based on this view, learner agency may not always be described as a complex interaction of varied elements. Because, the non-agentive aspect gives a structural direction to learning. The agentive aspect determines a learner’s likelihood to succeed. Thus, it depends on the learner to progress or succeed based on their exercise of autonomy and centredness when there is the structural framework that allows it. This can be found when Farr and Song (2011) spoke about the linguistic and identity practices of multilingual students if allowed in the mentioned framework. The study by (Irie & Brewster, 2014) mentioned above can be an evidence to this where the learners are provided the same inputs, but the one who exert the agentive elements achieved likelihood to succeed. Similar derivation is suggested by the literature review of Xiao (2013), who spoke about the self-regulated learning, self-efficacy, identity, and motivation, which are components of the learners’ belief system that influences learner agency. Such components define the manner and the success of a learner in terms of the capacity to make decisions, plans and their execution to fulfilment. Thus, based on Benson (2001), without the learner being an active agent, they cannot effectively learn a foreign language. There is a conscious initiative and action central to language learning. In that light, Teng (2018) had given primary importance to autonomous learning that may allow the optimal use of learning opportunities.

The literature review as laid out might have presented the agentive and non-agentive aspects in a parallel setting in regard to understanding learner agency. As Mercer (2012) stated, a holistic view of the literature review findings suggest that they are interrelated and inter-dependant. This has been established in the earlier paragraphs. The structural elements of the non-agentive aspect present a structural framework through standardisation. The learners’ individual characteristics, such as autonomy, efficacy, motivation or action or reacting on stimuli or motivation, define how the learners will proceed with the optimal use of the standard structure in place. However, the only limitation may arise if the standard structure does not allow or motivate learners’ agentive elements. Citing and based on (Dam, & Legenhausen, 2017; Little, et al., 2017), learners need stimulation and being harnessed to develop their agency. This may also mean that if there is no conducive environment, there may not be any progress in learning or the learners may not be able to develop the sense of agency. This deduction could be seen in the study conducted by Lantolf and Genung (2002), who addressed the fluid nature of motivation. When the student started to be highly motivated and as an effective language learner, they did not seem to be aware of the manner the language teaching programme was about to be carried out. It was when most of the language teaching programme was spent on grammatical pattern drills, the learning environment was not found conducive for her to learn that shifted her motive to merely fulfilling the language requirements (Lantolf & Genung, 2002).

To reiterate Miller and colleagues (2015), agency is fluid and may be altered or reshaped based on the narratives or the sense that learners gave to the context surrounding the learning. The self-regulation or the exercise of autonomy is defined by the learning environment, which encompasses the classroom and outside the classroom factors, which in turn shape and develop their belief system. Thus, agency may not be limitedly seen as what (Biesta & Tedder, 2007, p. 134) defined, “the ability to exert control over and give direction to one's life” It is also reacting to surrounding context driven by the sense the learner develops. In regard to the ability to exert control, the study by (Irie & Brewster, 2014) evidences it when one student was able to exert control and the other could not. With regard to the reactive perspective, it is evidenced by the study by Lantolf and Genung (2002), where the learner shifted her motive based on how the learning programme was executed. These two examples also evidence the earlier statement that structural framework gives a foundation where learners could exert their control and autonomy. Where such foundations do not allow, which is what the learning programme did, learners cannot exercise control, self-regulation or optimal use.

The arguments of (Lantolf & Pavlenko, 2001; Zimmerman, 2001; Sturtevant & Kim, 2009) present a holistic understanding of learner agency. Agency bridges motivation and actions. It is constantly shaped and reshaped (Lantolf & Pavlenko, 2001, p. 145). The self-regulation of learners holds primary importance to understanding agency. Because, the cognitive, behavioural and motivational factors define self-regulation. Such factors also interact with factors outside the classroom environment (Lantolf & Pavlenko, 2001; Zimmerman, 2001; Sturtevant & Kim, 2009). This in turn seems to consider the substance of learning, which is, for instance, considering the linguistic and identity practices in the standardised language learning, which (Larsen-Freeman, 2019; Farr & Song, 2011) argued to have been left out. The holistic understanding of learner agency cannot be limited to systematic development but is an integrated process where learners’ performance is actively influenced by their social interaction and experiences in their communities. Such an understanding does not categorised learners, but seeks a substantive approach to learner agency by incorporating learners’ cognitive and behavioural aspects as well as narrative of their life experiences.

4.4. Curriculum and self-assessment socio-cultural influence

The discussion so far has suggested an understanding of learner agency comprising a constructive learning, which is supported by the institutional support and input that provide adequate motivation and opportunity. This section is an extension of the earlier discussion on the agentive and non-agentive elements in learners’ agency. The literature review discussed aspects of curriculum and its relevance to learner agency. Similar to the discussion around agentive and non-agentive elements, literature around curriculum and self-assessment will also present that curriculum and self-assessment form the bridge between the institutional, structural standard framework and the exercise of autonomy, self- regulation and self-efficacy.

The literature review found that curriculum plays an important role in the development of learner agency. It compared the traditional approach and the pragmatic approach adopted in curriculum. The former focuses on the curriculum experiences of the learners as a part of their learning and wider life. This is relevant to the structure of the curriculum, which may limit the teaching and learning (Raffo, et al., 2021; Young, 2014). This makes a similar sense to the non-agentive elements that (Larsen-Freeman, 2019; Han, 2004; Molenaar, 2008; van Geert, 2011) made about the learner agency. Based on their arguments, the traditional approach indicates that the curriculum would provide the comprehensive input and the manner of systematic development and socialisation, derived from statistical data regarding events and experiences of the learners. Such a structural framework may constrain the activities of the teacher, students and the learning itself.

Unlike the traditional approach, the literature review regarding curriculum in respect to learner agency indicates the importance of substances rather than the events associated with the learners. Based on the argument of (Raffo, et al., 2021; Young, 2014), the curriculum should focus on substances and it reflects the social factors beyond the acts, beliefs and motivation of individuals. The earlier discussion regarding the relation between agentive and non-agentive elements is relative in regard to the pragmatic approach of curriculum and development of learner agency. They are also interrelated and interdependent. The literature review finding, thus, suggests that curriculum gives a platform for the learner to learn something that might have been found impossible by some or sets the parameter for learning. Thus, based on the arguments by (Raffo, et al., 2021; Young, 2014; Lee & Cha, 2017), curriculum has specific purposes. They presented a balanced role of the curriculum by treating curriculum as a way to transmit knowledge as well as depending on the capabilities of the learners, adopt a relational perspective to understand the subject and the objects together.

Curriculum represents a continuous experience encompassing the capabilities, activities and experiences of the learner. This is the pragmatic approach where it gives a structure enabling learners to exercise the autonomy and self-regulation to fulfil their expectation and goals. The example of listening logs for extensive listening in a self-regulated environment by (Lee & Cha, 2017) is appropriate here. This relational finding is similar to the earlier discussion related to (Han, 2004; Irie & Brewster, 2014; Raoofi, et al., 2012; Lantolf & Pavlenko, 2001), based on which it could be stated that parameter of learner agency is defined by the curriculum and the likelihood of a learner’s success depends on their effective use of their own agentive elements. Curriculum is the bridge between the agentive and non-agentive elements. If it allows the liberty to learners to make choices in terms of making decisions regarding plans and objectives, or provides a conducive environment, it may effectively lead to development of learner agency.

Self-regulation, self-efficacy, or the exercise of autonomy will determine the chances of success of the learners. The effectiveness of the curriculum will be whether it allows learners to exercise these agentive elements. The same observation is found relevant to the discussion regarding self-assessment. They are relevant to the construct of learners’ belief system, which is found in the literatures of (Schunk, 1989; Bandura, 1994; Lantolf & Pavlenko, 2001). Reiterating dispositions (Wyatt-Smith, et al., 2014), learners should be enabled to make their choices and as such new ways may be developed to capture their learning skills and competence. The BOSSA model proposed by Sweet and her colleagues (2019) seems to represent this finding. While, it provides the standardised self-assessment protocol that could be implemented on a large scale, it also serves as an integrated tool which when supported by proximal performance opportunity, training, and practice allows learners, instructors and language programmes to conduct the assessment successfully.

BOSSA represents a structural framework that also allows learners’ exertion of control and autonomy. Reading the literature findings of (Roever & Powers, 2005; Andrade, et al., 2008; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006), the focus on the substance or learners’ centred approach could also be seen regarding the formulation of self-assessment tool. Understanding learner agency, as seen earlier, is not understanding either the learners’ inherent or internal elements or the external environment (the social or learning context). It is both. While Roever and Powers (2005) found that the meaning of the responses may differ subject to the language on which the assessment is administered, Andrade and Valtcheva (2009) and Nicol and Macfarlane‐Dick (2006) stated that self-assessment should allow an articulate expectation for the task set by the learner or the teacher or both. This will further allow learners to monitor their own progress, which represents the exercise of control and autonomy; and use feedback to guide revision, which represents the optimal use of learning opportunities, Teng (2018) stressed upon.

Understanding learner agency involves understanding the self-belief system of the learners and their belief system regarding the learning environment. Reiterating Haugen (1971: 20) , the language ecology is “the study of the interactions between any given language and its environment”. This itself indicates that learner agency adapts to the changes brought about by the interaction between the two belief systems. Literatures of (Cross, 2009, p. 32; Reinders & Lazaro, 2011; Moore & Reindeer, 2003) in addition to the other relevant works mentioned in the literature review indicate that learner agency is a continuous narrative, adaptation and shaping of the belief system influenced by the learner’s own individual characteristics and the social, cultural and the learning context. This was seen in the curriculum and the self-assessment discussion, or the discussion regarding the relation between agentive and non-agentive elements. This is also reflected in the arguments of (Fogle, 2012), who linked the family and classroom settings and the influential role of the parents’ beliefs and ideologies regarding language learning. Fogle also articulated the influence of norms and practices over the identities and productions of the learners. Thus, the literature review suggests that learner agency cannot solely be understood from socio-cultural context, as Sullivan and McCarthy (2004) argued, which only focussed on cultural systems and activities, or from a dialogical perspective, as Miller and colleagues (2015) argued, which focuses on feeling, living and expressive experiences of the individuals. Understanding learner agency needs a holistic approach, considering both socio-cultural context and a dialogical perspective. Thus, the consideration of learners’ use of their cultural resources as well as the personal stories, including the emotional and agentive experience.

Cross (2009: 31) rightly stated that “Agency exists in the dialectic between social structures created through cultural-historical tools (policy) and the [ontogenetic] subject”. Learners are subject to the learning processes, which are not merely the learning processes per se, but also include the environment including the social and life experiences, self-regulation, or autonomy.

4.5. Conclusion

Thus, the literature review found that learner agency has diverse characteristics, but mostly categorisable between the self-characteristics and surrounding environment. The literature review suggests that understanding the characteristics and environment is a complex affair. Because, as Reinders and Lazaro (2011) argued, learners are engaged in a highly personal, variable and contextually influenced process. Further, they have different levels of skillsets and needs, which may also shape their goal setting, monitoring and learning opportunities. Thus, as Moore and Reindeer (2003) suggested, creating individualised teaching and learning may be complex due to a diverse range of interests and needs. In that light, reiterating the requirement of standardisation, for example a structural curriculum or assessment, which allows individual exercise of autonomy, may be the pragmatic approach. Such an approach may consider the cognitive, constructive and behavioural approach to understanding learner agency.

Chapter Five - Conclusion