Impact of Transport Infrastructure

Introduction

The chapter majorly throws light on how transport infrastructure and infrastructural services have a positive effect on international trade, and how quality and safe transport infrastructure positively positive impact on international trade. Majorly, the discussion will focus on a range of transport infrastructure i.e. railways, roads, airports, and seaports, as well as the services provided in these transport sectors. Ideally, these are the major sectors within the context of physical infrastructure that are monumental in the movement of goods from one geographical area to the other through exports and imports – international trade. Besides, other mediating business services such as financial services will also be of importance to highlight because they play a fundamental role in supporting and mediating importers and exporters. Basically, these services cater to the logistics that help reduce the transactional costs involved in international trade; hence can be construed as supporting infrastructural services for international trade.

Against the understanding that international trade is crucially supported by infrastructure and support services, this chapter will go ahead to discuss how such infrastructural services can be made safer and effective through government policy and regulatory reforms. Ideally, these policies may be termed as complementary trade policies because they are a key in enabling gains from trade by enabling efficient, safe and quality of infrastructure. Besides, this chapter will discuss the relationship between domestic transport infrastructure and international trade, and whether there should be a balance in investment between domestic and international transport infrastructure. Ultimately, this chapter will highlight the importance of developing policy coherence in these complementary trade policies.

Inefficient Transport Infrastructure and Cost of Transport

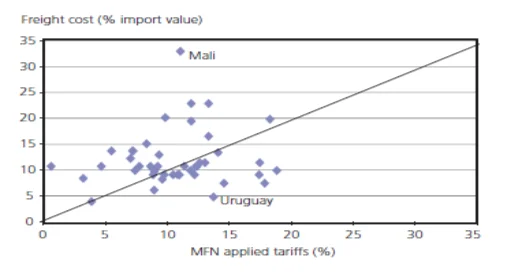

Talking of efficient transport infrastructure for international trade, a major issue that has gained the attention of researchers is transportation cost and how it creates a barrier to international trade. In a previous study by the World Bank, 168 out of 216 trading partners in the US cited that transport cost created higher barriers to trade than tariff barriers (WTR, 2004). Besides, according to reports by WTR (2004) on African international trade, the transport costs incidences for exports in most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa is five times higher than tariff costs (e.g. duty fees). As illustrated in fig 1 below, data from UNCTAD indicate that in Latin America countries such as New Zealand, The US, Africa and the Caribbean (represented by the observation above the 45-degree line), traders pay more transport costs to import goods than they pay for tariffs.

Existing literature reveals higher transport costs as a barrier to international trade varies geographically. For instance, WTR (2004) indicated that the cost of freight in developing countries is 70% higher than that in developed countries. Besides, from a continental perspective, the cost of freight in Africa has previously been estimated to be twice higher than the world average cost of freight.

Continue your exploration of Marketing Strategies in Restaurants with our related content.

There are many factors contributing to the transport cost differentials in different countries. According to WTR (2004), geographical characteristics such as the distance between different markets are major contributors to such differentials. For instance, Hummels (1999) estimated that a doubled geographical distance between markets may contribute to between 20-30% increase in freight estimates and that landlocked economies face an average of 50% higher freight rates than coastal economies. High transport cost has a negative impact on trade and inhibits the achievements of the benefits that accompany trade liberalization. In fact, according to WTR (2004), countries that enjoy a lower cost of different modes of transport have a relatively higher comparative advantage in terms of composition and volume of trade than countries that have a higher cost of transport. This is especially typical in air transport where countries with lower costs of air transport have a comparative advantage in the sector of time-sensitive goods (Limao & Venables 2001). Higher transport costs are usually a function of poor or inefficient transport infrastructure and are related to longer durations of goods delivery in international trade. Besides, quality and safe infrastructure may contribute to a big difference in transport costs. In fact, Limao & Venables (2001) estimated that if a country improved its transport infrastructure such that it moved from holding median position in the rank of 64 countries to being at the top 25 of these countries, its transport cost would reduce by an equivalent of 3,989 kilometres in sea travel and 481 kilometres on land travel, leading to a 68% increase in trade volumes. Therefore, to ensure that international trade runs smoothly and yields the desired level of growth, there is a need for greater focus on transport efficiencies, safety and quality both at national and international levels.

Integration between Transport Logistics and International Trade

Transport logistics and support services include a wide range of activities such as management and administration, storage and packaging. According to Harrigan (2010), these services are estimated to cover a significant share of total production costs in most European countries. Consequently, to achieve an efficient and quality and less costly transport network for international trade, it is monumental to integrate transport with the logistic services. Integrating transport with logistics help in eliminating various barriers to international trade such as border delays, direct charges and transport coordination challenges that may be required by transit countries before imports are let into the market. Apart from that, efficiently organized domestic logistics has a positive impact on the country’s competitive advantage in international trade. According to Hummels & Schaur (2013), sometimes the international transport network system may suffer from poor cross-country coordination of the system caused by customs delays, poorly integrated time schedules, poor communication about delays and poorly compatible standards. But when a country has established efficient logistic services, these problems can easily be solved. For example, efficient logistic services save the costs incurred by clients through concentrated cargo flows, reduced empty voyages and effective information sharing among operators (Koyak, 2013). This particularly exudes the important role of information and communication technology (ICT) as part of the logistic services.

ICT and Logistics as an Enabler for International Trade

The modern transport system in international trade is characterised by various modes of transport structures that are integrated within the operational modalities of logistics companies. According to Volpe Martincus & Blyde (2013), this integration has largely been enabled by ICT through the efficiency with which it connects various transport systems and markets. Consequently, a differential in the digitization levels between developed and developing countries have led to a difference in competitiveness and market access, with developing countries experiencing a diminishing trend of both. It is undeniable that there is a commonality in the characteristics held by both ICT and transport sectors. According to Simonovska & Waugh (2013), both sectors enable the accessibility and linkage if various remote activities, with a common characteristic of a network structure. Consequently, according to Volpe Martincus & Blyde (2013), there is a great possibility of establishing a sustainable relationship between physical travel and telecommunication. For example, the ability to send trade documents and files through the internet has eliminated the need to physically transport such files. Nonetheless, advancement in ICT has largely complemented the transport sector, particularly as evidenced by the use of telecommunication within the transport sector. First, it is important to note that companies offering logistics services to international traders have emerged as complementary to originally existing air-cargo firms, shipping lines, rail transport firms and road transport firms. Consequently, the international freight industry has transformed, with the help of ICT, from a fragmented sector to a more integrated transport system under the organization of transport and logistics companies (Volpe et al, 2013). But, the role of ICT in this transformation is quite clear. According to Yeaple & Golub (2007), ICT has enabled international traders to keep track of their products wherever they are transported to, and at any time. It has also enabled them to share information with customers, shippers, customs brokers and terminal operators thereby easily managing their supply chain to full fill ‘just in time’ customer requirements (Abel-Koch, 2013). Secondly, freight companies, with the help of ICT, have been able to extend their services by restructuring their production, transportation and distribution systems, with the assistance from logistic companies that have created a demand for new shipment services. As a result, according to Banerjee et al (2012), freight firms no longer only buy spaces in cargo planes and ships but also offer other services such as labelling and packaging.

Having established the important role of ICT in enabling effective logistics in international trade, it is possible to extrapolate that developing an integrated transport system across countries in order to build an efficient transport system may help reduce the cost of international trade by reducing the cost of transport and improving market access. Besides, the important role of policy coherence in regards to road transport as well as other supportive services such as ICT cannot be overemphasized. A more coherent policy effort would contribute to an establishment of efficient supportive services such as train inter-country train connections, improvement in container logistics, and efficient flow of production resources between various international sites.

Domestic Infrastructure and International Trade

In the context of developing countries, poor domestic transport infrastructure has largely been blamed for impeding international trade by disabling access to international markets. Yet, empirical evidence indicates that improved domestic road transport has the potential of improving the composition and volume of its international trade (Cosar, 2013). Besides, evidence by Rousslag and To (1993) suggest that the domestic component of international trade accounts for a significant portion of the cost of cross-border shipping of goods, and that a decade ago, the domestic freight costs in the US were almost equal to its international freight costs. Moreover, estimation by Atkin & Donaldson (2012) revealed that international trade costs in Nigeria and Ethiopia were 7 to 15 times greater than international trade costs in the US. As a result, various policy institutions such as World Trade Organization (WTO), World Bank (WB), and Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) have insisted that inefficient logistics sector and poor transport infrastructure has a negative impact on the competitiveness of developing countries in the international trade arena (ADBI 2009, WB 2009 and WTO 2004). For example, data produced by the WB indicates that in 2013, trade facilitation through the improvement of international trade was its single largest and most increased trade-related agenda. Hence, the importance of internal transport infrastructure to international trade is important in determining the trade-related importance of transport infrastructure to international trade. The importance of internal roads to international trade has been highlighted by various pieces of literature as well as quantitative research. For instance, evidence by Allend and Arkolakis (2013) revealed that shipping goods from coast to coast within the United States through interstate highways was around a third the cost of conducting the same shipment through a traditional highway system. Another researcher, Blyde (2012), estimated a reduction of between 20-30 % of the cost of transporting exports from remote locations to the port when the quality of road pavement improved from poor to good.

International versus Domestic Infrastructure

Whereas existing literature support that both international and domestic transport infrastructure has a positive contribution to international trade, a major question that still remains largely unanswered is whether more investment should be made on domestic or international infrastructure. Which among the two has a greater return? Works by Atkin and Donaldson (2015) indicate that researchers seeking to answer this question may need to be country-specific. Indeed, having highlighted evidence that the trade costs incurred in Ethiopia and Nigeria may be larger than that incurred in the US, one may extrapolate that more investment should be targeted at domestic infrastructure in the two countries than in the US. However, the accuracy of this extrapolation can be determined using the model of the firm, a theoretical perspective proposed by Martin & Rodgers (1995). First, domestic infrastructure is deemed as the infrastructure that facilitates domestic trade, while international infrastructure is deemed as the infrastructure that facilitates international trade. Against this backdrop, the model posits that companies tend to relocate to countries with better infrastructural development, in the presence of economies of scale, so as to offer goods and services to all markets at low costs. The model further holds that firms tend to make reference to better international infrastructure when identifying countries to relocate to under; the assumption that these countries have an infrastructure of international standard. Consequently, this has a negative impact on developing countries that still have poor infrastructure, and therefore investing in domestic road infrastructure in developing countries can help in enhancing international trade by attracting international firms. On the flip side, increased investment in international infrastructure will help in serving the developing countries’ markets by firms from countries with developed infrastructure. Hence, if, based on the model of the firm, investment in international and domestic transport infrastructure makes countries with rich infrastructure more attractive, the same may not be true for developing countries. It is only when poor countries invest in their domestic infrastructure that they will attract more international firms.

However, the model of the firm by Martin & Rodgers has not yet been subjected to an empirical test so far. This is probably because there is a difficulty between international infrastructure and domestic infrastructure, for example, it is difficult to tell whether the road from the port to the firm is domestic or international infrastructure. Besides, according to Olarreaga (n.d), it is problematic to assess how infrastructure impacts on income because ideally, the fact that one region is richer makes it easier for that region to invest in infrastructure.

Quality of Infrastructure

Not only is infrastructure an important enabler for international trade but also the quality of infrastructure. According to Cosar & Fajgelbaum (2013), this argument is based on the time required to move the goods between traders. For instance, the time spent in shipping goods does not only include the time spent on traveling but also time spent at the port organizing the administrative documents, conducting the clearance procedures, loading and unloading the cargo. Hence, delays in such processes may mean additional cost to the trader and this may affect trade, investment choices, comparative advantage and ultimately the importing country’s GDP. Whereas there is a paucity of empirical evidence to prove this point, a perfect example is given by Redding & Venables (2002) on Intel’s investment in Costa Rica. Ideally, Intel invested in a 300 million dollar microchip facility only after securing the government’s guarantee of a free and rapid customs clearance with minimum administrative and bureaucratic processes.

A Case Study of Kinshasa

The quality of road transport and its impact of trade has also been a matter of discussion in various pieces of literature. Ideally, the quality of road transport affects international trade in two major ways. First, according to Bernard et al (2010), poor road transport directly contributes to an increase in delivery time and the cost of road transport. This is especially highlighted in a case study by Minten & Kyle (2000) who highlighted how poor domestic road transport affects export trade in Kinshasa Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The authors begin by acknowledging that small and large scale farmers in the area of Kinshasa transport their farm produce to Kinshasa for domestic sale or exportation. The area is characterised by poor roads and long distance between villages yet traders must travel from Kinshasa to the villages to purchase the farm produce for export of sale in the Kinshasa market. Minten and Kyle (2000) also study the existing long distance between producers and the market, the poor quality infrastructure and how this affects the final prices of the goods sold in the market. Whereas traders can choose to either travel by road or by river, the distance between the market and the village through the river is long and takes relatively more time. Worryingly, Minten and Kyle (2000) found that the journey between the villages and the market via the river is about 300 kilometres and takes around 20 days to complete through the river compared to 4 days on road. Yet, only a small share of the product can be transported through the river, meaning that the time taken to reach the destination is quite crucial. Moreover, according to Minten and Kyle (2000), transport cost accounts for at least 30% of the wholesale price of goods when transported through the road, and 20% of the wholesale price of goods when transported by river. Upon analysing the relationship between incomes a transport cost throughout the supply chain, Minten and Kyle (2000) found that farmer’s share of the wholesale price declines at a rate of 3.4% per 100 kilometres. The analysis further indicated that whereas the share of transport costs increases at a rate of 3.1% in every 100 kilometre, the cost increases at a rate of 6.2% on bad roads. Ideally, this means that if a farmer lives 500km away from Kinshasa (400 km of paved road and 100km of dirt road), he/she would enjoy a 155 increase in producer income if the dirt road was improved to the paved road (Minten and Kyle 2000).

The effect of quality road transport has also been estimated to affect international trade through comparative advantage. For instance, if a trade sector like the textile industry is more sensitive to transport infrastructure than other sectors, it is likely that an improvement of transport infrastructure will improve the country’s comparative advantage in textile (Cosar & Fajgelbaum, 2013). In Yeaple and Golub’s (2002) analogy of the extent to which infrastructural development conducted by the government contributes to differentials in total factor productivity (TFP), the development of transport infrastructure appears to be a significant factor in the country’s growth and productivity through increased production and specialization. According to Yeaple and Golub (2002), road infrastructure emerges as an important factor especially in regards to transportation equipment in the sector of textiles and apparels.

Transport Infrastructure and International Trade In Developing Countries

UNCTAD has been interested in evaluating the important contribution of transport to trade and economic development in developing countries. First, it acknowledges that the availability of an efficient transport system contributes to economic development by enabling a reach into the global markets. In fact, at a UNCTAD delegates conference in Johannesburg, there was a call for an integrated policy making both at the regional, national and local levels to ensure that there was a safe and efficient transport for trade development in developing countries, especially in Africa. Ideally, this was a consequent of the recognition that improving transport and communication infrastructure a well as other related services could help to effectively gain from trade liberalization (UNCTAD, 2003). Particularly, a key to the delegates’ considerations included equipment for the movement of containerized goods (e.g. terminals, ports, air, rail, and road and sea connections), superstructure and infrastructure. Moreover, the delegates stressed the importance of involving the private sector to perform the role of partial financing and operation of such transport facilities – complementing the public sector (Atkin and Donaldson 2015).

Recently, globalization has played a major role in changing the approach to trade, transportation, and even production. Consequently, according to Cosar & Fajgelbaum (2013), companies have shifted their production to companies that offer a competitive advantage. A typical example of the impact that such a shift has caused on transport can be extrapolated from the case of China, which in 2003, experienced a 50% and 33% increase in imports and exports respectively compared to the previous year (2002) (UNCTAD, 2003). According to UNCTAD, (2003), this example depicts how transport and logistics can be an added value service in international trade. Besides, it shows how transport has become an integral component of international production and distribution of goods, and an enabler of competitive advantage for manufactured goods. However, according to Atkin and Donaldson (2015), more focus is needed in specialised services because the main providers of transport services are relatively a small number of carriers (e.g. P&O Nedlloyd, Maersk Sealand), and the chances of getting newcomers are relatively small.

Whereas the last decade has seen an increase in containerization due to the movement of goods using different modes of transport, there is an increasing trend of international transportation of goods being carried out on a door-to-door basis with the use of more than two transport modes (UNCTAD, 2003). Ideally, local providers of transport services are of great importance in playing the role of subcontractors within the multimodal transport chain because most consignees and shippers are often comfortable dealing with one party who assumes all the contractual responsibilities in the process of delivering goods.

High-quality transport services are also critical to the competitiveness of various countries and individual international companies. As a result, according to Cosar & Fajgelbaum (2013), the legal and international infrastructure in developing countries should be improved so as to create an enabling environment for transport services that enhance trade and development. Against this backdrop, Atkin and Donaldson (2015) acknowledge that most developing countries lack the legal framework to facilitate a door-to-door international trade, especially those that are facilitated by one party throughout the entire process leading up to the delivery of goods. Hence, there is a need for the international community to a coherent legal or policy regime that creates an enabling environment for the development of multimodal transport.

Besides, the proliferation of ICT in international trade has had a further impact on transportation systems in international trade especially through the emergence of sophisticated communication and operation systems used in bringing efficiency and controlling cost. Moreover, the development of ICT has contributed to the optimization of equipment use, leading to improved customer relations. However, according to Atkin and Donaldson (2015), some developed countries still do not have the necessary physical infrastructure to enable them to benefit from ICT. It is, therefore, necessary for such countries to invest more in such infrastructure because failure to which, they stand to miss out on efficient transport and logistics services that promote international trade and economic development.

Ideally, all the above-mentioned measures have a significant impact on international trade especially in regards to transactional costs of trade. But when countries take unilateral approaches to these issues while imposing global solutions, there is likely to be an increase in transaction costs of international trade, impacting negatively on traders especially those from developing countries (UNCTAD, 2003).

Zhuawu & Soobramanien (2014) acknowledge that while analysing the impact of infrastructure on trade, a major challenge encountered by researchers is identifying the type of infrastructure that has a direct impact on trade. Ideally, this challenge is often eminent because the concept of infrastructure is often wide and encompasses a range of elements that have an indirect impact on trade. However, researchers have addressed this challenge by looking at various determinants such as the efficiency of customs and border services, transport infrastructure, and ICT infrastructure.

In regards to custom and border services, researchers have particularly been interested in it due to its crucial role in facilitating international trade. According to Bernard et al (2010) customs is the interface between exporters and importers. Moreover, Cosar & Fajgelbaum (2013) argue that the role of customs is not only important in the context of international trade but also has an impact on the socio-economic welfare of citizens because it controls the flow of goods and services, thereby ensuring that illicit or undeclared goods and services do not move into the country.

Therefore, the quality of customs and border check infrastructure is a major determinant of a country’s capacity to trade with its partners i.e. the rapidity with which goods are released and the efficiency in valuing, clearing and checking compliance with port regulations determine how fast goods move in and out of the country (Bernard et al 2010).

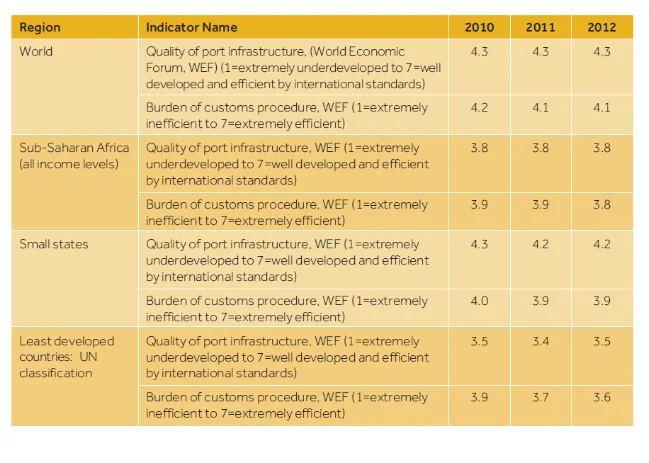

Recent research has largely concentrated on how various factors facilitating trade, including measures related to customs clearance infrastructure benefit international trade. For instance, research by WB indicates that when the global capacity of trade facilitation (e.g. ICT used in trade transactions, customs, transparency in trade regulation and port efficiency) is improved above the global average, world trade would increase to a tune of 377 billion US dollars (Wilson et al, 2005). The same analysis by WB also revealed that unilateral trade facilitation has a large potentiality of benefiting trade exports. These findings corroborate with the findings of Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2013), which estimated that if the then WTO Doha Development Round measures were comprehensively implemented, total trade costs would reduce by 10% in developed economies and by 13 to 15.5% in developing economies (Zhuawu & Soobramanien 2014). Consequently, according to Zhuawu & Soobramanien (2014), reducing global trade cost by 1% would lead to an increase in world income by at least 40 billion US dollars, most of which would be experienced in developing countries. Worryingly though, developing countries face various infrastructural challenges, part of them being inefficient customs infrastructure (Bernard et al 2010). For instance as illustrated in fig 3 below, customs procedures in Sub Saharan Africa, small states as well as LDCs have been shown to be characterised by inefficiencies, which have been worsening in the periods of 2010 and 2012 compared to the world’s level of customs efficiency which has averagely remained constant during the same periods. Cosar & Fajgelbaum (2013) attribute these inefficiencies to a lack of resources and the perception that investing in such infrastructure would be burdensome.

As a form of cure to these inefficiencies, the WTO recently developed a Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) that not only meant to harness the members’ commitment to enhance international trade through import-export facilitation through improvement of custom procedures, but also developed measures meant to help developing countries to implement various trade facilitation measures for purposes of harmonization and simplification of international trade.

Ideally, during the signing of the TFA, the developed countries members of the WTO agreed to support least developed countries (LCDs) and developing countries by using their private sector trade facilitation activities to help in promoting effective implementation of the TFA (Zhuawu & Soobramanien 2014). But, whether this agreement will contribute to increased efficiency of customs in developing countries is a matter of hope. Moreover, it is expected that this agreement will enable an effective and efficient domestic economic growth in developing countries by enabling small businesses to acquire new export markets through various measures like transparent customs procedures, or reduced time for processing customs documents.

Another element of infrastructure that has a direct impact on international trade is transport infrastructure. As hinted earlier in this study, transport costs may present a greater barrier to international trade than tariffs. According to Cosar & Fajgelbaum (2013), this is particularly true for developing countries that are either islands, landlocked or those that generally have remote markets. Nonetheless, it is believed that closing the transport infrastructure gap in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), small vulnerable economies (SVEs) and LCDs will contribute to sustainable development through the improvement of international trade. Moreover, if the existing transport infrastructure is rehabilitated, both domestic and international trade will be facilitated through the increase in competitiveness and reduction of cost of trade. Nonetheless, trade facilitation, through improvement of transport infrastructure, will also catalyse the economic transformation of industrialization by adding value to production processes (Zhuawu & Soobramanien 2014). For example, if more roads are constructed, land along the constructed roads shall increase in value to attract both job seekers and investors.

But according to Zhuawu & Soobramanien (2014), most SSAs SVEs and LCDs have underdeveloped transport infrastructure, a majority of it not matching the international standards of quality and quantity, thereby hindering their competitiveness. For instance, most of the road transport infrastructures in SSAs were built during the colonial era for the purpose of extraction and transportation of resources to the industrialised countries (Bernard et al 2010). Besides, Cosar & Fajgelbaum (2013) remark that road infrastructure in some countries was destroyed during the prolonged civil war, causing a great impact on the productive sectors of such countries. Today, these transport infrastructures cannot meet the standards and demand of growing economies and therefore are a constraint to both national and international trade.

Another issue that has largely been highlighted by researchers is the quality of transport infrastructure and how it affects international trade. For instance, as illustrated in fig 3, Zhuawu & Soobramanien (2014) indicate that most SSAs SVEs and LCDs have lower standard transport infrastructure and that some small states have still not made any attempt in developing their transport infrastructure to meet international standards.

One major argument posited as a reason for poor quality transport infrastructure in developing countries is that these infrastructures are poorly maintained due to financial constraints. Besides, developing transport infrastructure is an expensive affair and therefore some developing countries cannot afford quality projects. This assertion corroborates with the data produced by African Development Bank estimating that to meet the infrastructure deficit, Africa will have to invest at least 39 billion US dollars annually until 2020 from the year 2014 (Zhuawu & Soobramanien, 2014). Yet, reports by Zhuawu & Soobramanien (2014) also indicate that the Development Bank of Southern Africa finds the transport infrastructure in transitional development corridors not bankable partly due to unaffordability. However, despite the high cost involved, considerable efforts have been made to improve the quality of road transport, especially in recognition of the importance of road transport to the developing economies both at national and regional levels and the need to improve the transport network to facilitate international trade.

References

- UNCTAD, Review of Maritime Transport (2002 and 2003a); WTO - IDB; Hummels (1999a).

- UNCTAD, Review of Maritime Transport (2003a).

- Limao N. & Venables J. (2001) Infrastructure, geographical disadvantage and transport cost, Policy Research working paper

- International Trade,” Canadian Journal of Economics, pp. 208–221.

- Atkin, D., and D. Donaldson (2012): “Who’s Getting Globalized? The Size and Nature of

- WB (2009): “World Development Report: Reshaping Economic Geography,” Discussion paper, World Bank, Washington, DC.

- WTO (2004): “World Trade Report 2004: Exploring the linkage between the domestic policy envi- ronment and international trade,” Report WTO/WTR/2004, World Trade Organization (WTO), Geneva.

- Allen, T., and C. Arkolakis (2013): “Trade and the Topography of the Spatial Economy,”

- Blyde, J. (2012): “Paving the Road to Export: Assessing the Trade Impact of Road Quality,”

- Atkin, David and Dave Donaldson, 2015. Who's getting globalized? The size and nature

- Martin, Philippe and Carol Rogers 1995. Industrial location and public

- Olarreaga M (n.d) Trade, infrastructure, and development, Development policies working paper.

- B. Minten and S. Kyle, “Retail Margins, Price Transmission and Price Asymmetry in Urban Food Markets:

- Yaeple S. & Golub S (2002) International Productivity Differences, Infrastructure, and Comparative Advantage, Department of Economics University of Pennsylvania.

- World Trade Report (WTR) (2004) Infrastructure in Trade and Economic Development , Coherence.

- Hummels, D., and G. Schaur (2013): “Time as a Trade Barrier,” American Economic Review,

- Simonovska, I., and M. Waugh (2013): “The Elasticity of Trade: Estimates and Evidence,”

- Volpe Martincus, C., and J. Blyde (2013): “Shaky Roads and Trembling Exports: Assessing the Trade Effects of Domestic Infrastructure Using a Natural Experiment,” Journal of International Economics, 90(1), 148–161.

- Volpe Martincus, C., J. Carballo, and A. Cusolito (2013): “Routes, Exports and Employ- ment in Developing Countries: Following the Trace of the Inca Roads,” Inter-American Development Bank, mimeo.

- Yeaple, S., and S. Golub (2007): “International Productivity Differences, Infrastructure, and Comparative Advantage,” Review of International Economics, 15(2), 223–242.

- Abel-Koch, J. (2013): “Who Uses Intermediaries in International Trade? Evidence from Firm-level

- Banerjee, A., E. Duflo, and N. Qian (2012): “On the Road: Access to Transportation Infras- tructure and Economic Growth in China,” NBER Working Paper No. w17897.

- Bernard, A. B., J. B. Jensen, S. J. Redding, and P. K. Schott (2010): “Wholesalers and Retailers in US Trade,” American Economic Review, 100(2), 408–13.

- Cosar, A. K. (2013): “Adjusting to Trade Liberalization: Reallocation and Labor Market Policies,” University of Chicago Booth School of Business, mimeo.

- Cosar, A. K., and P. Fajgelbaum (2013): “Internal Geography, International Trade, and Regional Specialization,” NBER Working Paper No. 19697.

- Wilson, J S, Mann K L and Otsuki, T (2005). ‘Assessing the Benefits of Trade Facilitation: A Global Perspective’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3224.

- Zhuawu C. & Soobramanien Y. (2014) Infrustructure for trade development, The commonwealth, Issue 105. P.2-8.

- UNCTAD (2003) efficient transport and trade facilitation to improve participation by developing countries in international trade, TD/B/COM.3/60 3 October 2003.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts