Dementia: A Growing Health Crisis

Chapter One: Introduction To The Study

Introduction

One of the greatest threats to brain functioning is dementia, which is defined as the loss of cognitive functions, including remembering, thinking, and reasoning, to such a great extent that an individual daily life is interfered with. As of 2018, dementia prevalence among adults aged 65 years and older stood at 5.2 million people or 11% of the UK population (Oxtoby et al., 2018). Total costs estimated for long-term care, healthcare, as well as a hospice for those living with dementias stood at $236 billion in 2016, and this is expected to reach even higher levels with increases in the aging population (Alzheimer's Association, 2016).

One of the Healthy People 2020 goals is to reduce costs and morbidity associated with dementia and to enhance or maintain the quality of life of patients. As a result, there is a need to improve the diagnostic accuracy of the various types of dementias that usually result from different neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Despite the establishment of pathological and clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia, close to 15% of patients continue to be misclassified (Garn et al., 2017).

Dementia has trivial social and economic effects, especially in medical and social care expenses, as well as the expenses of informal care. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the total global societal costs of the disease amounted to £660 billion, which is equal to 1.1% of the total Gross Domestic Product globally (WHO, 2020).

Dementia can also have a significant impact on families and carers of the patients. The physical, psychological, and financial burdens might be overwhelming to the families who may be forced to seek additional support from health, social, financial, and legal organizations.

People with Dementia are sometimes denied the basic rights and freedoms similar to others. For instance, in the UK, just like many other countries, these patients are subjected to physical and chemical restraints even when universal regulations dictate that people have a right to freedom and choice.

Background of the Study

To understand dementia, we need to understand how it develops; according to Mayo Clinic, Dementia is a result of damage to or loss of nerve cells and their connections in the brain. Nerve cells fire nerve impulses by releasing neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters are chemical signals in the brain that initiate signals. Dopamine, which is also termed as 3, 4-Dihydroxytyramine, serves as a neurotransmitter in the brain; it refers to chemicals neurons released to transmit electrical signals from one neuron to the next chemically. Dopamine is crucial in various brain functions, including motor control, executive function, arousal, motivation, reward, and reinforcement via the signaling cascades. The cascades are exerted through binding to receptors at projections located in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, the ventral tegmental area, and the substantia area of the human brain (Klein et al., 2019). The substantia region is characterized by nigrostriatal pathways that project dopaminergic neurons from the pars compacta or input area to the dorsal striatum, and this is essential in learning motor skills and controlling of motor functions. A hallmark of Parkinson's disease involves dysregulations in motor control, which can result from the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway. The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is characterized by the mesolimbic pathway, which projects dopaminergic neurons from the prefrontal cortex to the nucleus accumbens of the cingulate gyrus, amygdala, olfactory bulb's pyriform complex, and the hippocampus. Emotion processing and formation are the responsibility of the dopaminergic projections in the cingulate gyrus and amygdala.

The above parts can be visually represented in the image below

Dopaminergic neurons present in the hippocampus are associated with working memory, learning as well as the formation of long-term memory. The olfactory bulb's pyriform complex has the responsibility of enabling humans to have a sense of smell. Dopamine is also released in situations that are pleasurable in the mesolimbic pathway, which causes arousal while also influencing behavior or motivations (Volkow et al., 2017). As a result, individuals seek out pleasurable occupations or activities for release of dopamine, which binds to dopaminergic receptors present in the prefrontal cortex and the nucleus accumbens. An increased projection activity to the nucleus accumbens plays a significant role in reinforcement behavior as well as addictions in more extreme cases. Dopamine neurons also make up the tuberoinfundibular pathway in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, which is responsible for projecting to the pituitary gland and inhibiting secretions of the prolactin hormone. Dopamine emanating from neurons in the arcuate nucleus is released in the hypothalamohypophysial blood vessels supplying the pituitary gland with dopamine and inhibiting prolactin production. It can help in preventing hyperprolactinemia, which, when left unmanaged, can impact fertility and bone density, leading to osteoporosis as well as neurological symptoms in some cases.

The presence of various pathological changes in the dopaminergic system bears both clinical and Pathogenetic relevance in cases of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Neurons that form the nigrostriatal pathway have been found to have various pathological changes, including a decrease in dopamine content and neuronal loss (Martorana and Koch, 2014). All these changes suggest the apparent involvement of dopamine in non-cognitive symptoms and the cognitive decline of Alzheimer's disease. Apathy occurrence, which is an adverse prognostic sign in both Alzheimer's disease and the elderly, is considered a consequence of dopamine transmission impairments evident during normal aging. Other studies have shown that dopamine and its derivatives are low in early-onset Alzheimer's disease and that dopamine D2 and D3 agonists like rotigotine can have rescuing effects on Alzheimer's disease patients. They can accomplish by restoring cortical plasticity, therefore, suggesting new Alzheimer's disease therapeutic strategies. Various investigations have also shown that through D2-like receptors, cortical excitability is increased by dopamine, and through D1-like receptors, cortical acetylcholine release is increased. Thus, the idea that dopaminergic system disruption is associated with Alzheimer's disease and other dementia pathophysiology is supported, and this can enable novel approaches to therapeutic developments. Even as the therapeutic developments progress, one great concern in dementia is the social inequality in accessing health care. Various studies have addressed this issue and have come up with substantial interventions that would assist in achieving equity in the dispensation of services. For instance, the World Health Organization (WHO) offers a global action plan on public health response to dementia. The plan seeks to improve standards in addressing dementia for all countries. The plan has been adopted by most countries since the deficits exist even in most advanced economies. There are two most crosscutting principles with the plan; first, universal health and social care coverage for people with dementia. Second, equity- this principle emphasizes that all public health initiatives should support gender equity and minority groups. These principles are well-founded, but they might not fully resolve the confounding ubiquity of social inequalities in dementia care.

The rationale of the Study

Dementia is a clinical syndrome rather than a disease. It is usually referred to as an acquired condition where multiple cognitive impairments are present that are sufficient to interfere with daily living activities. It is commonly progressive but not necessarily. One of its most common deficits involves memory impairment, but other domains like language, visual perception, praxis, and mainly executive functions are often involved (Barkhof and van Buchem, 2016). Progressive difficulty with daily living activities is experienced with increasing function loss due to these cognitive problems. Dementia can develop from various diseases, many of which have relentless continuous courses with an insidious onset. They are characterized by long durations like 5 to 10 years from diagnosis as well as relatively prolonged end-stage periods where all independence and self-care are lost. Age-related incidences are the most common cause of dementia. However, the condition is not a normal part of aging. The most common cause is neurodegenerative diseases. Enormous burdens are placed by dementia on patients, families, carers and health and social care systems. The identification of the relationship between dopamine and dementias and the causes of neurodegeneration can result in the establishment of evidence-based diagnostic criteria as well as new and effective treatments. Dementia is caused by neurodegeneration, especially from neurodegenerative diseases, which are debilitating and incurable conditions that lead to progressive death and degeneration of nerve cells and brain neurons. They include various conditions primarily affecting neurons in the human brain resulting in dementia or problems with mental functioning as well as movement problems or ataxias. Examples of neurodegenerative diseases include Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is considered the main form of dementia, which currently affects 0.5% of the global population translating to 45 million people (ADI, 2016). Substantial evidence in recent discoveries from early AD mouse models as well as late-onset patients shows that dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area become compromised. The degeneration of dopamine neurons leads to lower dopamine outflow in the nucleus accumbens and hippocampus. These correlate with impairments in hippocampal neuronal excitability, memory, synaptic plasticity, and reward performance (Nobili et al., 2017). Pharmacological interventions have also been consistent with these observations with manipulations that aim to increase dopaminergic transmission in the cortex and hippocampus, improving cognitive impairment, synaptic functions, and memory deficits, which emphasizes the critical role of dopamine for proper brain functioning. Currently, people living with dementia are at high risk of social inequalities. The limited access to healthcare among the older people, women, minority ethnic groups, and those with fewer economic resources is becoming wider and wider compounding communication challenges and social isolation among the patients. With an increasing population of older people in the UK, the potential impact of the disease in the NHS is thus significant.

Research also indicates that patients from the minority group (Asians and African) access diagnostic services much later after the condition has progressed into later phases. After being diagnosed, these people are also less likely to receive dementia medication, proceed to research trials or receive comprehensive care such as 24-hour amenities (Langballe et al., 2014). Both personal and communal socioeconomic disparities have a substantial contribution to social inequalities in dementia care. For instance, having a lower income reduces the chances of receiving counseling services. In the current situations in comparison to the standard of equity, as highlighted in the national dementia plans (Department of Health, 2011), a significant population of people with dementia are not receiving optimal healthcare. Besides, they lack the opportunity to contribute towards and gain from research (NIHC, 2013). These inequalities also contribute to excessive access to risk-reduction involvements regardless of different prior needs in risk reduction. Economically, persistent inequalities imply that funding interventions, especially in research, target the advantaged groups. Moreover, medical and care costs are potentially not allocated to those who are in need equitably (HCSD, 2014). The degree of social inequalities in mental illnesses, even in the most developed countries, implies that only rigorous interventions from multiple players could improve the situation. This undertaking can be drawn from the experience of heart disease, where concerted efforts built strong interventions to enable equity at all levels of healthcare. Prevention and care among women, mostly being seriously disadvantaged (WHO, 2015), robust measures from sponsors, care providers, and policymakers need to be initiated to provide solutions for these problems. Fortunately, the growing research in general healthcare, especially in social inequalities, is also growing in mental health. The knowledge from these studies should thus be translated into concerted policies in a timely manner. Also, solid efforts from all parties in alleviating social inequalities in dementia are required to progress more towards equitable access to care and treatment for all patients with dementia.

Treatment of people with Dementia

Ideally, there would be treatment today for Dementia to prevent symptoms such as Alzheimer's or at least stop it on its tracks. However, only Alzheimer's treatment is available, and it is mostly associated with treating symptoms. A category of drugs known as cholinesterase inhibitors is mostly provided to the patients to maintain neurotransmitters in patients. This drug has proven to increase cognitive function among patients with dementia symptoms if they are prescribed in the early stages (Cooper et al., 2017). Despite this advancement, research is still undergoing to develop vaccines and also to produce medication that might stop the progression of the symptoms. Nevertheless, most patients do benefit from occupational therapy, physiotherapy, and also social care in residential homes (Gilliard, 2005). The treatment of behavioral syndromes in dementia patients has focused on the use of psychotropic drugs (Cummings & Mega, 2003). Studies conducted in nursing homes and hospitals and also in the community also confirm that psychiatric medications are usually used in elderly patients with dementia (Jobski et al., 2017). Because of this constant use, guidelines governing the use of psychotropic medications in such institutions have been developed (Mathews et al., 2002). As the number of the aging population seeks to increase, so does the cases of dementia. The available resources are also prone to deterioration, which means that demand exceeds supply. This is the main reason for healthcare inequality in the country. However, as the efforts to help the patients progress, the condition has the greatest impact on the patients and also their families. Various studies have sought to determine the role and influence of dopamine on mental health, as well as the social inequalities in the provision of healthcare. Researchers have recently found that levels of dopamine may provide clinicians with more clues of diagnosing Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. By studying dopamine rich areas of the brain like the ventral tegmental area, they sought to determine how Alzheimer's can be diagnosed earlier by examining how the area interacted with other brain areas. Results showed associations linkages between functionality and size of the dopamine rich area with hippocampus size and new information learning abilities (De Marco and Venneri, 2018). Structural and functional imaging changes in the striatum have shown that dementia with Lewy bodies, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease dementia are characterized by striatal dopaminergic deficits.

It has become increasingly important to make a precise diagnosis of dementia subtypes, especially to enable different clinical management approaches that will allow better patient outcomes. For neurodegenerative conditions, the call has been for making an early diagnosis with interventions being most active at prodromal stages. Therefore early detection can help in planning for the future and avoiding drug contraindications. Dementia researchers have agreed that enabling early diagnosis requires biomarkers as most symptoms are detectable years before dementia sets in (Thomas et al. 2019). Clinical signs are not sensitive or specific enough for prodromal stage diagnosis, and the most informative biomarker has been identified as assessing dopaminergic function through brain imaging. The identification of the relationship between dopamine and dementias and the causes of neurodegeneration can result in the establishment of evidence-based diagnostic criteria as well as new and effective treatments. Apart from early detection, policymakers such as the Department of Health have identified that reducing inequalities in receipt of treatment would also help in improving the health of the patients in the country. There is little evidence on the influence of dopamine levels in dementia, while some of them mostly focus on the function of neurotransmitters such as Norepinephrine to influence behavior. Besides, Therefore, this study aims to examine the impact of dopamine on the dementia condition, drawing inferences from previous undertaken primary research studies.it also discusses various factors that contribute towards inequalities in receipt of treatment among patients with dementia.

Objectives of the study

This research seeks to achieve the following objectives

To establish the link between dopamine and dementia

To examine various social and economic inequalities that impact available treatment for patients with dementia

Research questions

Does low/high dopamine levels in the human brain affect behavior in dementia patients?

What socio-economic factors contribute to inequalities in receipt of treatment among dementia patients?

The aim of the study

This research seeks to determine whether dopamine is associated with cases of dementia by comparing the manifestations of Dopamine dysfunction to common dementia complications. It will also study the social inequalities present in receiving treatment among patients. Additionally, it will provide some recommendations to ensure the inequalities are minimized to facilitate equity in healthcare. The study will draw inferences from other relevant primary-focused studies relevant to the topic of study.

Chapter Two: Literature Review

Historical Background

The association of Dopamine with Dementia has been researched for a long time and is still under consideration (Trillo et al., 2013). The dopamine system follows through various transformational steps during the physiological aging process. Generally, these studies identify that the decline in the discharge of dopamine from its terminuses, the decrease dopamine transmitter expression in particular Dementias, and the anterior cortex of humans are characteristics typically observed in the brain while it is aging. The story of dopamine and its association with brain reactions, attitudes, and emotions dates back in 1957. In this era, the perception was that dopamine was a neurotransmitter in the human brain and not just a foretaste of norepinephrine (Carlson et al., 1972; Freedman & Wo, 1974). At this time, various studies started to emerge to find more knowledge on the function of dopamine in the human brain and its direct association with brain functions. In this course, Arvid Carlson, a pharmacologist, developed a test to determine the amount of dopamine in the human brain, which he found out that the greatest concentration of dopamine exists in the basal ganglia (Carlson, 1993). Carlson's researches were among the works that led to several investigations into the story of dopamine. For instance, an experiment conducted by Arnold et al. (1973) led to a depletion of dopamine and resulted in a loss of movement control. These kinds of symptoms are similar to the clinical indications perceived in neurological sickness, Parkinsonism (Holmes et al., 2001). Investigations relating to dopamine never ended there Carlson (1993), and Anorld (1973) found out that L-dopa, an antecedent of dopamine could effectively treat Parkinsonism symptoms, and this is still one of the drug treatments today. In 1977, the dopamine theory was developed by several researchers (Carlson, 1993; Fagius et al., 1983) that emphasize the role of dopamine in the advancement of extrapyramidal side-effects of neuroleptic drugs. The reticence of primary dopamine function is a fundamental element common to various to neuroleptic medication. The reward and dopaminergic pathways of the dopaminergic system are majorly the targets for the psychosomatic and the extrapyramidal activities, respectively, of these medications. Even though the significant intrusion in dopamine function in dementia cannot be excluded, the direct association between dopaminergic and other neuronal coordination needs to be investigated in more detail. Today, dementia with Lewy bodies is the origin of neurodegenerative dementia of older people with a projected occurrence of 16% to 25% of incidents as per autopsy studies (McCleery et al., 2015). Community prevalence projections differ more widely with percentages of between zero to five among the elderly and zero to thirty percent among older people with dementia (Walker & Walker, 2009). Besides, the medication strategies employed on dementia today are based on the neurotransmitter replacement approaches used for other neurodegenerative illnesses such as Parkinsonism and Alzheimer's. Hopefully, with the increased attention to studying dementia, especially with the effects of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, treatment might be developed.

The usage of neurotransmitter –based approaches for the medication in dementia is among the current issues affecting current studies today. Evidence claims that these neurotransmitter strategies might lessen the behavioral symptoms of dementia. However, their safety, efficiency, and long-term effects are yet unknown (Kandimalla & Reddy, 2017). Besides, when particular disease processes on dementia are created, drugs based on supplementing neurotransmitter systems will much likely to be helpful to ameliorate symptoms.

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of Dementia

The behavioral defects that are linked with dementia disrupt patient care and pose a management challenge to the care provider. Some of the behavioral and psychological symptoms associated with dementia are psychotic traits such as delusions and hallucinations along with those behaviors without psychotic traits, including depression, anxiety, aggressiveness, and uncooperativeness (Cummings & Mega, 2003). Patients with dementia exhibit some forms of disrupted agitated behaviors at some point in the course of their illness (Holmes et al., 2001). According to Herrmann et al. (2004), 18 to 65 percent of dementia patients experience aggressive behaviors, which have a detrimental impact on them and also to the caregivers. Unfortunately, because of these symptoms, the people are not knowledgeable about how they should suppress such kinds of symptoms in people they are taking care of. Most of them would put them under chemical or physical restraint for the fear that they would cause harm to people. On the other hand, caregiver burden and stress and poor relationship with people with dementia can also be among the factors that cause maltreatment.

Socio-economic inequalities

Several studies have been conducted with the major aim of addressing social inequalities in access to healthcare among people with dementia. For instance, Smith & Gill (2020) studies dementia needs among patients in a UK hospital. The authors identify that reducing risk factors could be the key means of reducing the global burden. Further, it supports the interventions by the public health of England, which continues to generate evidence from risk reduction from various knowledge. Socio-economic treatment inequalities most often arise since people with dementia or carers from the less privileged cannot negotiate for better healthcare systems in efforts to seek more desirable treatment. Cooper et al. (2017) have identified various socio-economic factors affecting psychotropic prescribing, which have been linked to differential access to alternative amenities, including psychological therapies or distinct patient or carer expectations. In previous studies examining the probability of people with dementia with physical health conditions being referred to secondary care, inequalities linked with socio-economic factors ensued more in the lack of explicit direction (Shah et al., 2011). Besides, inequalities among older people and females were apparent in all circumstances. In conclusion, evidence from various researches in both animal and human subjects supports an association between noradrenergic dysfunction and behavior. More particularly, patients with personality disorders such as dementia and have anxiety disorders all show a blunted growth hormone, including dopamine, which actively disrupts noradrenergic control. When comparing between demented patients with aggressive behaviors and non-aggressive patients, there are higher levels of aggression when dopamine levels are overproduced and under-produced or altered in this case. Nevertheless, the exact knowledge of what happens during each of these situations, i.e., low levels and high levels of dopamine, needs further research to assess the association of dopamine and behavior in dementia patients. On the other hand, various studies have tried to increase knowledge on the sociological impact of dementia on the patients. Most evidence highlight that socio-economic inequalities in access to healthcare among people with dementia need robust measures to ensure equity in the dispensation of care services.

Chapter 3 Methodology

This study employed a systematic review of peer-reviewed works of literature to collect data and find conclusions. The procedure involved critically appraising research studies and synthesizing findings qualitatively. Qualitative research techniques are useful in ascertaining the significance of a phenomenon and its impact on particular variables (Schratz, 2019). The phenomenological practices were employed to study the influence of dopamine in people living with dementia. According to Creswell (2011), qualitative research techniques are appropriate when the researcher is trying to understand the underlying behavior or attitude present between two variables. Also, this approach develops frameworks and produces relationships of meaning that build new knowledge in a particular field (Clark et al., 2008). Along with the systematic analysis of works of literature, the study used the grounded theory in arriving conclusions. Morse et al. (2016) define grounded theory as a systematic approach in the social science field involving the development of theories using methodical deducing and analysis of information. In this regard, this study also used inductive reasoning along with the deductive approach of arriving at conclusions. The procedures employed in this study are further discussed below.

Literature search

A literature search is a systematic process of searching pieces of evidence related to the subject under study (Christmals et al., 2017). The study employed a literature search through several databases, including the University of Warwick's library search, Encore, the web of knowledge, and Google scholar. These databases provided a wide range of works of literature that were used to build the research question by assessing the existing literature with an eye on gaps that are open for further research. Besides, the process also assisted in concluding making evidence-based principles, which is an essential step of the research process.

Search Strategy

It is vital to develop a search strategy to identify relevant and valid works of literature when conducting a systematic review (Creswell, 2011). Therefore, this study employed the University of Warwick to locate and select relevant works of literature from the Encore database. It also used Google Scholar as a complementary source of evidence to assist in the research process. These two sources were selected because they are part of the primary research; the resources were ranked based on their originality and efficiency. These sources were given prominence because they contain up-to-date pieces of evidence, which means that the study used the latest published information. Secondly, they have meticulous review procedures ensuring the journals are of the highest quality. And lastly, they are always accessible whenever reference is needed. Various subject headings linked to the subject under investigation were identified and selected during the search procedure. The search process involved typing the keywords in the search box of every database; several works of pieces of literature were identified using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see table 1). The keywords used in the search process include Dopamine, Dementia, behavior, behavioral conditions, age, socioeconomic factors, and gender, among others. The Boolean operators such as 'and, or' were employed to link the keywords to identify the most relevant and valid pieces of literature (Coughlan et al., 2013). Lastly, before selecting a study, its weakness and strength were evaluated to determine its significance; for instance, the research questions were assessed to decide whether or not they are linked with the subject under study. Secondly, the study's aims and goals were assessed to determine whether they were clearly defined. Lastly, the research design was assessed to see whether it was appropriate (Holland & Rees, 2010).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion strategy employed in this study included all peer-reviewed articles (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods) relevant to the subject topic under investigation. The second approach included sourcing for relevant evidence published in English; no limit was applied to the year of publication. However, the conclusion part of the discussion incorporated evidence published from the year 2010 to 2020. The latest pieces of evidence made sure that the findings were relevant to the current times. Conversely, the exclusion criteria involved abstracts and other works that were not related to the research topic. This approach ensured that the study has logical precision, and only crucial evidence was used (Burns, 2005).

Main themes

The study's significant issues included the impact of dopamine in dementia people and the behavioral types in low and high levels of dopamine in people with dementia. In the results category, terminologies connected with dopamine, including other neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, serotonin were used. Also, other classes of memory loss and thinking, such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease were included. These terms were put in the perspective of conditions related to memory loss among older people. Additionally, socio-economic factors such as age, gender, income, and ethnic groups were used in discussing the sociological landscape of dementia. These factors were used to describe the health inequalities present in receipt of treatment among dementia people.

Limitations of the search

The study could have omitted valid information from the various kinds of literature because it wasn't possible to consider all works of literature found in the user databases. Also, UK research on this topic was limited, which necessitated the use of other resources and theses done in other countries, especially Australia and Spain, which has transferrable healthcare to the UK (Grosios et al., 2010).

Critiquing tool

The study employed both an inductive and deductive reasoning model for reviewing the works of literature. Besides, it used a structured critical approach in identifying the strengths and weaknesses of every research to conclude.

The trustworthiness of the study

According to Williams et al. (2009), dependability is the level of consistency in a research's procedures such as methods, and research designs, and, ultimately, its findings. In this regard, the study provided an audit trail by highlighting how shreds of evidence were collected, and the criteria used in arriving at conclusions. By adequately documenting the research procedures, an outsider would develop an audit trail and provide healthy criticisms to the research as required. The study employed detailed, excellent, and thick descriptions in the findings section to make quick decisions concerning the transferability of the study. This component increased the external validity of the research. Besides, the author tried to reduce control for bias during the study. For instance, the author ensured there was no fabrication of evidence. All pieces of evidence from the works of literature were presented as they appeared — this action aimed at representing original findings and reduce the aspect of bias. Additionally, the author made sure that there was no plagiarism in any way. Every content and idea from the works of literature were cited and referenced appropriately. Lastly, the author included both negative and positive pieces of evidence to limit the aspect of bias in the study. Evidence presented was thoroughly checked to ensure the conformability of the research to the required standards, as highlighted by Sarantakos, (2012).

Chapter 4 Discussion of findings

Dopamine and behavioral

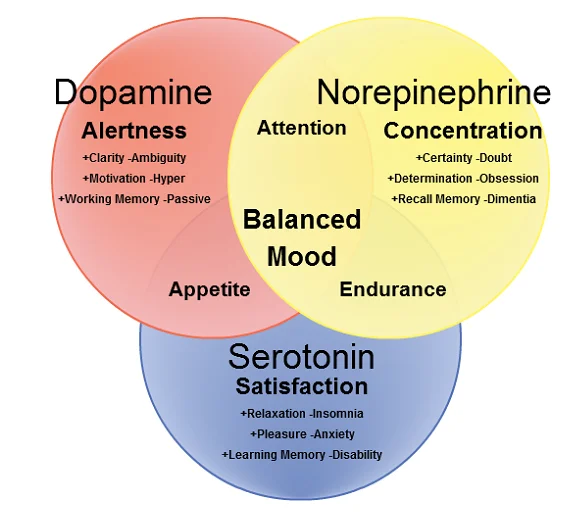

Evidence suggests that neurotransmitters do not act independently (Backman et al., 2010; Patterson et al., 2019); these brain chemicals interrelate and affect each other to ensure a chemical balance within the body, as shown below.

The study reveals that there is a strong association between serotonin and dopamine systems in both structural configuration and their functions. According to Boureau & Dayan (2011), serotonin appears to limit the production of dopamine, meaning that low levels of serotonin lead to an overproduction of dopamine in the brain, leading to impulsive behavior. This concept is also supported by den Ouden et al., (2013), who argue that serotonin inhibits impulsive behavior in people while dopamine boost impulsivity. This evidence shows that dopamine and serotonin have reversal impacts relating to hunger and behavior. Neurochemical and neuropathological disruptions in both dopamine and serotonergic systems have been linked to a group of thinking and social symptoms, including dementia and Alzheimer's disease. For instance, Becker et al. (2011) ascertain that Alzheimer's disease is associated with alterations in 5-HT signal transduction. 5-HT are serotonin receptor that plays a crucial role in neuronal plasticity. Preliminary studies show that changes in the 5-HT receptor coupling with guanine nucleotide-binding (G) protein have confirmed in the superior frontal cortex in the brain (Colloby et al., 2012). However, some other studies find that coupling is preserved in the cerebral cortex. Also, uncoupling of phosphoinositide (PPI) hydrolysis from 5-HT release in the anterior cortex tissue among people with dementia's brains compared with age-matched control subjects has also been established (Bolam & Pissadaki, 2012; Esposito et al., 2013). The research on messenger systems is crucial since uncoupling suggests that neurotransmitter substitution approaches in dopamine and serotonergic systems would be ineffectual. Interruptions in the dopamine and serotonergic systems have also been examined in various dementing conditions. For instance, Ferrer (2012) finds that serotonin binding was decreased by almost half among patients with vascular dementia. Additionally, insufficient levels of serotonin were also present in vascular dementia, especially in cortical and subcortical grey matter. Nevertheless, a more recent study fails to establish serotonin deficiency in the patients, as mentioned above (Martorana et al., 2013). However, further evidence concludes that serotonin deficits depend on the type of vascular dementia and also the level and location of injuries. Additional evidence also determines serotonergic and dopamine alterations in Pick's disease and Lewy body dementia (Rodgers, 2011). Serotonin and dopamine have been linked to nonpsychotic behavioral and psychological symptoms in both post-mortem and clinical research works. For instance, a clinical study using cerebrospinal fluid levels of the 5-HT established that levels of 5-HIAA in the cerebrospinal fluid were linked with nonpsychotic behaviors such as anxiety, apathy, and depression (Moreno et al., 2010). In a post-mortem study, reduced cortical levels of 5-HT were established in patients who had a history of aggression as compared with patients who had no aggression history. On the other hand, normal levels of 5-HT receptors were established in patients who were not aggressive (Martorana et al., 2013). Other studies seeking to measure putative peripheral marker in the dopamine and serotonergic activity have also been conducted. For example, Cai (2014) assessed the linkage between binding to the platelet serotonin carrier co-ordination (an indicator of serotonergic activity) and behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia among patients with Alzheimer's. The identified behavioral and mental traits in dementing illnesses were aggression and delusions. The group with aggressive and delusional behavior showed a substantially lower serotonergic action as compared to the group without behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementing illnesses. Though a study by Perkovic et al., (2018) finds no changes in the concentrations of platelet serotonin binding spots among Alzheimer’s patients and other control subjects when subjects with depression had been omitted. Even though Perkovic et al., (2018) were able to find a link between serotonin affecting dopamine levels to result in depression, post-mortem research was unable to determine this connection (Wuwongse et al., 2010).

Since patients with symptoms of depressions were not omitted in the Perkovic et al. study while the group without signs of agitation experienced apathy, it is uncertain if the connection with agitation and delusions can be entirely associated with comorbid depression among some of the patients. Besides, platelet 5-HT operation might not be sufficient to qualify as a peripheral marker for the significant serotonergic system. In support of this notion, Ruljancic et al. (2013) find a negative association among cerebrospinal fluid 5-HIAA and receptor indications in other neuropsychiatric patients.

Dopamine levels

As mentioned by Patterson et al. (2019), serotonergic neurons function closely with dopaminergic neurons. For instance, serotonergic neurons resulting from the raphe nuclei are known to have a synaptic connection with dopaminergic neurotransmitters and also regulate the release of dopamine in the midbrain, striatum, and nucleus accumbens septi (Li et al., 2011). From this evidence, it is clear that serotonergic neurotransmitter can either inhibit or increase the production of dopamine. The dopaminergic system has been associated with symptoms including depression, apathy, among other psychotic conditions among non-demented patients. Therefore this system is responsible for influencing the behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. Even though alterations occurring in the dopaminergic system among Alzheimer's patients in several post-mortem studies, dopamine is less affected as compared to other biogenic amines (Lawlor, 2013). Alterations in the dopaminergic system could comprise presynaptic changes in the dopamine carrier as well as the postsynaptic loss of striatal dopamine receptors (Pan et al., 2019). A loss in dopamine type 2 receptors could proliferate in mild stages of a person with dementia; at this stage, they would exhibit extrapyramidal behaviors. A neuroimaging research has shown that alteration in dopamine metabolism increases significantly as the cognitive weakening progresses (Pievani et al., 2013). Nevertheless, research studies focusing on patients with Alzheimer's that identified the cognitive impaired as a controlling factor have failed to establish the association between psychotic behaviors and defects in the dopaminergic system (Bierer et al., 1993; Aisa et al., 2010). Similar findings might be determined in other dementing symptoms. For instance, in Lewy body dementia, dopamine metabolic factors were substantially diminished in patients not exhibiting hallucinations along with serotonergic defects (Moreno et al., 2010). Further evidence suggests that aggressive behaviors might be related to the relative maintenance of dopamine function among patients with dementing symptoms. A study by Victoroff et al. (1996) demonstrates that the preservation of substantia nigra neurotransmitters is associated with aggression and violence. Further research conducted in vivo backs these findings. According to Trzepacz et al., (2013), aggressive patients’ exhibit cerebrospinal fluid homovanillic acid intensity similar to their age-matched control subjects, patients without aggressive behaviors exhibited lower levels. Also, in support of this notion, Takeyoshi et al., (2016) find increased violence during perphenazine medication associated with alteration in plasma Homovanillic acid among with Alzheimer's disease. These findings support the association between aggression and dopamine. Therefore, dopamine maintenance might be connected with aggressive behaviors in patients. It is also credible to conclude that cholinergic and serotonergic dysfunction might also be existent and essential for this behavior. However, no pieces of evidence are supporting this claim yet.

Reduced levels of dopamine in the body result in difficulties in initiating movement, stiffness, postural deformities, akinesia, and apathy (Takeyoshi et al., 2016). Studies involving NE and MHPG find mixed outcomes with normal, higher, and reduced levels of noradrenergic in effect among people with dementia (Dupuis et al., 2012). Noradrenergic systems are a multifaceted structure, and it might be possible that both decreased and improved noradrenergic activity happens at distinct times and in various sections of the central nervous system in dementia. On the other hand, Norepinephrine might be a central neuron for regulating an individual's mood and response in stressful situations. However, studies show that alterations in the dopaminergic system have been associated with the etiology of depressing and motor signs linked with dementia and not psychotic symptoms (Bierer et al., 1993). Also, people with Alzheimer's along with significant depression exhibit higher levels of pathological conditions, especially in the substantia nigra, even though they possess different dopamine levels as compared to Alzheimer's patients without depression (Pan et al., 2019). When it comes to motor symptoms, studies find out that dopaminergic systems have a vital role in the enhancement of Parkinson's symptoms mostly exhibited in people with dementia (Dupuis et al., 2012). This supposition is supported by Engelborghs et al., (2008), who finds a significant relationship between cerebrospinal fluid dopamine metabolite intensities and dysfunction motors in people with dementia. A considerable amount of studies finds that the changes in the dopaminergic system are linked with particular operational and behavioral results in Alzheimer's patients, as reviewed in table 2 in the appendix section. Dopamine neurotransmitters present in the mesocorticolimbic and nigrostriatal paths supply nerves several structures in the striatum and the anterior cortex parts of the brain, which are thought to facilitate feelings of enthusiasm and motivational behavior (Lowe et al., 2009). Several pieces of evidence find that dopamine facilitates the motivational pursuit by ascribing enticement salience to reward motivation. Truly, dopamine influences casually to enticement salience and is responsible for the usual 'reward-seeking' behavior (Burke et al., 1994; Mulligan et al., 2013). Further evidence shows that dopamine agonists facilitate the reward-seeking attitude, whereas dopamine antagonists lessen the reward-seeking trait (Dombrovski et al., 2010). Clarke et al. (2010) describe apathy as the absence of sensation, anxiety, or motivation. Many research works have suggested a dopaminergic basis of apathy in Alzheimer's disease, bearing in mind the connection between dopamine and motivation or the 'wanting' behavior. Imaging studies have associated pathophysiological alterations to dopaminergic neuron-containing structures and emotions of apathy in people with Alzheimer's (Thomas et al., 2019).

Clinical features of dopamine-dependent symptoms

Apathy is another neurobehavioral symptom linked to dementing symptoms. Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) are linked to dementing symptoms, including Alzheimer's, causing the disease progression mostly connected to neuroleptic supposition, and are absolutely and negative extrapolative indication. Both apathy and Extrapyramidal symptoms are subordinate to dopamine dysfunction, and their emergence is an indication of illness development for patients with mild cognitive deficiency and Alzheimer's patients (Mitchell et al., 2011). These two conditions are linked to the Amyloid beta burden, and both conditions could co-exist in an individual. Even though commonly defined, not all patients with Alzheimer’s might experience apathy and Extrapyramidal symptoms in their life. Only a half might exhibit apathy symptoms, while a third could exhibit Extrapyramidal symptoms in the preliminary stages of the illness. At later stages of the disease, accomplice physiological maturing, Extrapyramidal symptoms are commonly expressive and can be easily diagnosed among all people with dementing symptoms (Mitchell et al., 2011). Today, Amyloid-beta intensities can be easily detected in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with dementing symptoms and generally be used for diagnostic determinations (Richard et al., 2012). Because Amyloid-beta has a low threshold, they are crucial in individuating cognitively compromised persons. However, they cannot be applied in the evaluation process of where the oligomer-mediated injuriousness has extended to the cortical or subcortical nuclei (Starkstein et al., 2009). Findings from neuropathological and clinical research work point out that there is a concern for various individuating groups of people with Alzheimer's disease. This classification would possibly be characterized by a clinical mark to get patient's stratification for medical determinations (Richard et al., 2012). These undertakings might assist in individuating patients with more projecting cholinergic deficiencies as regards those exhibiting with signs of dopamine dysfunction, among others.

Recent clinical research works define the characteristics of Alzheimer's patients via their various degrees of advancement. Groups of Alzheimer's diagnosed individuals were selected and categorized by multiple extents of executive functions of dysfunction, high concentration of cerebrospinal fluid and phosphorylated tau comprised with a low concentration of Amyloid beta 1-42, the incidence of apathy and little or absent response to pharmacological medication with cholinesterase inhibitors (Mitchell et al., 2011; Horvath et al., 2014). In these studies, the findings showed the presence of both apathy and extremely high levels of cerebrospinal fluid tau protein, which were associated with the more rapid development of cognitive deterioration (Schmidt et al., 2011). According to Trillo et al. (2013), tau pathology is a mark of neurodegeneration, and it is not particular for Alzheimer's. Trillo et al. (2013) further find tau pathology in the brain stream of Alzheimer's disease. In support of this finding, Attems et al., (2012) claim that a certain percentage of tau pathology in the monoaminergic tract might characterize the substate for extreme neurodegeneration processes in Alzheimer’s instances. This condition indicates that a group of Alzheimer’s disease patients could be susceptible to develop dopamine dysfunction linked symptoms. Likewise, the monoaminergic tract has suggested having the ability to regulate the physiologic amyloid-synthesis procedure (Himeno et al., 2011). From these studies, it is safe to conclude that the progressive dysfunction or disintegration of monoaminergic neurons could signify an early phase for heightened amyloid secretion and amyloid-connected deterioration of neurons.

Dopamine and depression and anxiety levels

Evidence suggests that Alpha-synuclein seems to initiate depression among patients with dementing symptoms (Weintraub et al., 2005). Therefore, in treatment determinations, selective targeting of dopaminergic pathways might offer symptomatic relief for depressive symptoms among Lewy bodies dementia patients. In a postmortem study, the pathological load of Alpha-synuclein was found to be substantially higher in the dorsal striatum and insula among patients with Lewy bodies' dementia contrasted with Parkinson's incidences (Lowe et al., 2009). In another study, Lewy bodies’ dementia cases exhibited extremely higher Alpha-synuclein (α-synuclein) levels in the substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area, and nucleus accumbens signifying that the intensities of Alpha-synuclein are responsible for these symptoms. The upsurge of pathology levels in the subcortical and cortical section among patients with Lewy bodies has been witnessed in major depressive disorder and also in the amygdala in Alzheimer's disease cases Sato et al., (2007). α-synuclein interrelation with dopamine metabolic actions and diffusion might have significant effects not only in the loss of neurons and motor symptoms but also across the progress of depressive symptoms in Lewy bodies' symptoms (Kertesz et al., 2008). According to Klein et al., (2019), dysfunction in striatal connectivity with limbic and cortical parts is assumed to develop several neuropsychiatric symptoms in Lewy bodies’ dementia. Kertesz et al. (2008) find an association between Alpha-synuclein pathology and depression in people with Lewy Bodies dementia intensely connects the spread of pathology from mesolimbic and mesostriatal dopaminergic neurons. The above results show the interrelation between various types of pathology, which differentially impacts the brain configurations within dopaminergic pathways, enhancing specific clinical phenotypes. Dopaminergic Alpha-synuclein pathology seems to influence depression, thus, pursuing these particular pathways and contrivances might offer a reprieve from depressive symptoms among Lewy bodies dementia patients. The incidence of neuropsychiatric symptoms among Lewy bodies’ dementia patients is high (McManus et al., 1999), with depression being recorded as the most prevalent psychiatric symptom in Lewy bodies' patients, often coming first than motor symptoms. Besides, depression is also linked with cognitive dysfunction as well as a faster rate of intellectual deterioration among patients with Lewy bodies dementia (Tohgi et al., 1991). Monoaminergic insufficiencies in depression are deep-rooted, including serotonin, NE, and dopamine (Herrmann et al., 2004). In another study, Parkinson's disease patients with depression symptoms showed heightened serotonin transporter, especially in the limbic and raphe nuclei regions. At the same time, there were decreased levels of 5HT1A receptor concentrations in limbic parts of the brain (Borroni et al., 2010). The insufficient levels of dopamine especially in the nigrostriatal pathway which is a result of progressive Alpha-synuclein linked with neurodegeneration and injury of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra cause a depletion in dopamine in the dorsal striatum and the progression of motor symptoms among people with Lewy bodies dementia (Herrmann et al., 2004).

In this case, the mesolimbic dopamine pathway is believed to send dopaminergic projections from the ventral tegmental area in the interior of the midbrain to several cortical and subcortical sections, such as the nucleus accumbens available in the ventral striatum. Thus, the ventral tegmental area has a crucial role in pathophysiology in attitude disarrays and intellectual dearth (Torres, 2010). The deep interrelations between the insular cortex with basal ganglia and limbic system also function as a significant integration factor for mental and emotional handling (Messiah et al., 2020). Also supporting this rationale is Holmes et al., (2001) arguing that because anhedonia and loss of motivation are significant symptoms of depression, it is probable that dysfunction of dopaminergic connectivity is engrossed in influencing depressive comportments.

The link between Low Dopamine and Memory Impairment

Evidence suggests that the approach of diagnosing dementing symptoms can be changed by studying the dopamine-firing cells (De Marco & Venneri, 2018). Besides, this study suggests that the loss of these cells is associated with low dopamine, which impairs memory formation. Therefore, by using a specific type of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in scanning 51 healthy adults as control subjects, 29 with slight cognitive impairment and 28 with Alzheimer's, the research found a linkage between the Ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the hippocampus parts of the brain. The hippocampus creates new memories in the brain when the VTA doesn't secrete sufficient levels of dopamine for the hippocampus; the latter won't function as needed. From all these studies, it is reasonable to argue that research on dopamine and dementing symptoms is still at infancy. However, efforts are still in a course to explore the issue. Yet, on the topic of dopamine, it is crucial to discuss the emergence of depression as linked to dementia. Irrespective of age, dopamine deficiency substantially increases the risk of developing hyper levels of depression. In turn, it is assumed to increase the chances of dementia and other related symptoms. D'Amelio et al. (2011) argue that the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons implies the decreased importance of daily activities and the attitude changes linked with dementing symptoms. Further, they explain that loss of memory and depression are two related factors. In their study, they conclude that the foundations of dementing symptoms such as Alzheimer's are not found in the part of the brain that is responsible for memory, instead found in the section which is responsible for mood disorders.

Healthcare inequalities

Dementia diagnosis has been linked with fewer physical health checks and primary care contacts regardless of the government's efforts in prioritizing healthcare access among these people. According to Cooper (2017), patients often have difficulties in arranging, remembering, and showing up to an appointment with doctors. Health inequalities have become increasingly crucial for consideration as knowledge for potential risk-reduction in dementia heightens. The following factors are associated with health inequalities in the UK.

Gender

In the UK, 62% of the patients are female, while 38% are male (Fenton, 2016); this could be the fact that women have a higher life expectancy rate than men, while age is the biggest risk attribute of dementia. Whereas some pieces of evidence have found various factors might affect the number of men and women with the condition, there is no solid conclusion that women are more likely to suffer from this condition at any age.

Milne & Williams (2000) also note that women patients have more disability and disease than their male counterparts; thus, it is a great concern that they receive less healthcare nursing. Further, in the study, Milne & Williams found out that women are less likely to receive an annual evaluation, recommending that the content of the evaluation needs to be inspected since pre-emptive health assessments are essential. Another study by Russ et al. (2013) notes that women more often live solely because of their higher endurance. In this regard, the lesser possibility of having a co-resident carer could illuminate why women receive lesser healthcare services. As compared with men, Cooper, (2017)’s study finds that women were likely to introduce psychotropic treatment, but generally, much of these medicines were approved to women implying that they took them for longer. Therefore, more frequent medication evaluations could lessen needless psychotropic medication. Gender disparities are also evident in the accessibility to research knowledge because recruitment to dementia investigations are more likely to engage men than women (Bond et al., 2005). According to the Department of Health (2011), 1 in every four women is likely to receive support for depression as compared with 1 in every ten men over 18 years and above. Despite under-diagnosis among men, in later life, women are more likely to experience the death of a spouse, move into a residential care facility and suffer a physical illness, which later becomes a significant indicator for transforming cognitive weakening into dementia.

Education

The swingeing educational disparities in cognitive function, decline, and dementia prevalence are common. The differences are usually illuminated through differences in both intelligence that plump for education and neuroprotective impacts of education that develop cognitive reserve (Gilliard, 2005). Most healthcare services and activities such as advice and support are provided online. A study by ONS, (2013) notes that education levels are associated with the likelihood of using technology. Most uneducated people also live in the rural areas where education is at lowest levels. Furthermore they are not aware of the support and advice provided online by professionals.

Age

Dementia might not be an inevitable condition in growing old, but the risk of suffering the condition increases with age (HSCD, 2014). The increased risk could be due to factors linked with aging, including high blood pressure, increased prevalence of some ailments, and weakened body's ability to repair systems naturally (Gilliard et al., 2005). At least 40,000 people under the age of 65 suffer from dementia in the UK (HSCD, 2014). Studies show that these people are more likely to face stigma and difficulties, especially if they are carers of young children and are in employment (Fenton, 2016; Cooper, 2017). The UK Equality Act of 2010 necessitates that employers should offer reasonable workplace adjustments for people with disabilities. However, there is little evidence on how employers have dealt with these requirements for these classes of people, how problems are dealt with once the diagnosis is made, and how assessment for ability and fit for work is done.

Ethnicity

In the UK, there is a higher prevalence (up to 4 times greater) of dementia among black and south Asian communities (Department of health, 2011). In 2011, 25,000 out of the total over 100,000 diagnosed cases of dementia in England and Wales are from the above ethnic groups. The number is also expected to rise up to 50,000 by 2025 (Fenton, 2016). Individuals from this group are more prone to risk factors, including heart disease, high blood pressure, and other chronic illnesses, which increase the risk of dementia. Besides, these people are less likely to receive a diagnosis for the condition for various reasons including; Inability to access healthcare services Lack of understanding and awareness of dementia Frequency of stigmatization in some communities

Also in the UK statistics show that the majority of the people from the minority groups have or work in manual or low skilled jobs. Therefore, their income and standards of living in the older age mirror the employment in early life. The irregular patterns of work, such as long-term unemployment along with long-term illness, are some of the factors associated with people of minority ethnic groups. These factors deter them from contributing towards pension schemes, and thus most of them rely on state pensions, which are not sufficient to enable better access to healthcare when the condition arises (Shah et al., 2011). Averagely, the Black Caribbean citizens are the lowest income earners in the UK, followed by British Indians, and then the highest earners are British pensioners (ONS, 2013). 70% of the minority group live in deprived areas as compared to 40% of the white population. Therefore, poverty among minority ethnic groups also contribute to healthcare inequality among patients in the UK. Language barriers and lack of awareness of available opportunities to participate in community activities hugely contribute to social isolation in some of the patients. For instance, Somali people in the UK have poor English-speaking ability, with almost 50% of the female population having no skill at all. In comparison to their male counterparts, 24% of the male Somalis have poor English language skills (ONS, 2013). Assistance from voluntary sector corporations that offer psychosocial support and enhance access to services is crucial for these minority groups. Ethnic groups that are small, widely dispersed, and lack economic and political powers generally have poor healthcare engagement activities contributing to inequalities in the system (Cooper et al., 2017). Agitated aggressive patients with dementing symptoms have been confirmed to have increased reaction to the 5-HT discharging agent known as fenfluramine contrasted with dementing aggressive patients without agitation (Ni et al., 2013). From the studies, it is reasonable to conclude that all reviews give inconsistent proof to connect serotonin and dopamine dysfunction with psychotic signs and with fear and depression in dementing illnesses. This knowledge is helpful in increasing understanding of dementia as a major condition affecting mental health in humans. Besides, the various factors discussed increase understanding of health inequalities to enable effective policy formulation.

Recommendations for the socio-economic inequalities

The department of health is tasked to ascertain the substantial effect of social factors –especially those that limit social connectedness and psychological motivation on the risks of prevalence and progress of poor mental health, intellectual weakening, and dementia in the country. Thus, it should come up with solutions to improve the current situation. Shelving development of policy formulation has potentially significant effects on the need and cost of care interpolations. These inequalities can only be addressed by robust policies both locally and nationally; the following are key recommendations from this submission. Additional concerted efforts are necessary at the national level to back local intervention in addressing the issue of lack of access to learning opportunities and physical indolence in the later lives of people. Lack of greater and focused action on social determinants would result in poor mental health and dementia at an early stage among minority groups. Secondly, approaches for action need to be established on three fundamental phases, they include pre-retirement, post-retirement, and late old age. In this regard, the policymakers should help people develop financially until the later stages in life by ensuring they get access to good employment opportunities that incorporate 'age-friendly' and 'equity perspective.' The department of health, along with other government units, including the department of pension, trade unions, and other local agencies, should work collaboratively to prepare people for retirement.

Conclusions

Most of the studies examining the dopaminergic system in dementing symptoms have established a reduced intensity of dopamine receptors, reduced intensities of extracellular dopamine, reduced concentrations of dopamine metabolites and reduced dopamine reuptake by Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type. The results for all these studies cumulatively suggest a dopaminergic neuronal obliteration in the brain of Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type patients. Most of these findings are a result of post-mortem research works, and it is crucial to ascertain that conclusions are slightly limited because of the limitations integral in this approach of methodology. Dopamine is believed to influence the emotions of reward-seeking, and amusement, and, probably, the dysfunction of the dopaminergic system in patients with dementia illnesses is primarily responsible for the high prevalence of apathy. Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) investigations find that dementia type of Alzheimer’s disease patients who have apathy feelings contain reduced blood perfusion to their frontal cingulate and orbit anterior cortex. These are parts in the brain that are innervated by dopaminergic neurons and are linked with sensations of gratification and motivation. Currently, there are about 850,000 people with dementia in the UK (Prince et al., 2015), and the number is expected to exceed 5 million by 2021. Among these patients, about 30% experience psychotic symptoms, hallucinations, while some experience severe cognitive shortfalls than likened control subjects without psychotic symptoms. Equally, Alzheimer's disease patients experiencing psychotic symptoms are susceptible to rapid cognitive degeneration, a severe decline in function, and impulsive institutionalization. Various levels of dopamine dysfunction might happen during any stage of Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia. And as a result, most significant symptoms connected to dopamine dysfunction include the presence of apathy and extrapyramidal symptoms. The happening of these signs might be associated with the pre-existing brainstem pathology. Their affliction varies depending on the age of the patient, which is the most prominent risk factor connected with Alzheimer’s type of dementia.

Since most of these studies are post-mortem investigation and their application is limited, authors must collect data prospectively. This recommendation involves data from antemortem and drug use on distinct behaviors. For instance, neuroimaging methods, including SPECT, comprises of innovative approaches to establishing neurotransmitter variations in the antemortem brain. In dementia cases, these approaches might lead to the detection of certain receptor insufficiencies that might associate with non-cognitive components of the disease. Additional potential antemortem studies of central neurotransmitter roles are neuroendocrine challenge research to forecast response to medication, including prolactin response, among others. From the discussions, it safe to conclude that socio-economic factors such as age, gender, income, and education determine accessibility to treatment among dementia patients. Besides, there is not an equal chance of having physical or mental wellbeing in later life in the UK. There is a higher risk for deprived mental healthcare for people in vulnerable socio-economic groups, including the black and minority ethnic groups (BMI) and women. The focus of this submission is the inefficiencies in the accessibility of healthcare among people with dementia. By highlighting these factors, policymakers, sponsors, and care providers could help in developing better systems to ensure every person gets the right treatment to improve their wellbeing. Notably, reducing the stigma attached to dementia is crucial in enabling people to acknowledge and open up about the challenges they are facing in their lives because of the condition. This action would increase knowledge for research.

Conflict of interest statement

The study was conducted without any commercial or financial assistance, which could otherwise be identified as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Aarsland, D., Creese, B., & Chaudhuri, K. R. (2017). A new tool to identify patients with Parkinson's disease at increased risk of dementia. The Lancet Neurology, 16(8), 576-578.

- Aarsland, D., Cummings, J. L., Yenner, G., & Miller, B. (1996). Relationship of aggressive behavior to other neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer's disease. The American journal of psychiatry.

- Aisa, B., Gil-Bea, F. J., Solas, M., García-Alloza, M., Chen, C. P., Lai, M. K., ... & Ramírez, M. J. (2010). Altered NCAM expression associated with the cholinergic system in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 20(2), 659-668.

- Arnold, P. S., Racine, R. J., & Wise, R. A. (1973). Effects of atropine, reserpine, 6-hydroxydopamine, and handling on seizure development in the rat. Experimental neurology, 40(2), 457-470.

- Attems J., Quass M., Jellinger K. A. (2007). Tau and alpha-synuclein brainstem pathology in Alzheimer disease: relation with extrapyramidal signs. Acta Neuropathol. 113, 53–62 10.1007/s00401-006-0146-9

- Bäckman, L., Lindenberger, U., Li, S. C., & Nyberg, L. (2010). Linking cognitive aging to alterations in dopamine neurotransmitter functioning: recent data and future avenues. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 34(5), 670-677.

- Becker, J. A., Hedden, T., Carmasin, J., Maye, J., Rentz, D. M., Putcha, D., ... & Marks, D. (2011). Amyloid‐β associated cortical thinning in clinically normal elderly. Annals of neurology, 69(6), 1032-1042.

- Bierer, L. M., Haroutunian, V., Gabriel, S., Knott, P. J., Carlin, L. S., Purohit, D. P., ... & Davis, K. L. (1995). Neurochemical correlates of dementia severity in Alzheimer's disease: relative importance of the cholinergic deficits. Journal of neurochemistry, 64(2), 749-760.

- Bierer, L. M., Knott, P. J., Schmeidler, J. M., Marin, D. B., Ryan, T. M., Haroutunian, V., ... & Davis, K. L. (1993). Post-mortem examination of dopaminergic parameters in Alzheimer's disease: relationship to noncognitive symptoms. Psychiatry research, 49(3), 211-217.

- Borroni, B., Costanzi, C., & Padovani, A. (2010). Genetic susceptibility to behavioural and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer disease. Current Alzheimer Research, 7(2), 158-164.

- Burke, W. J., Folks, D. G., Roccaforte, W. H., & Wengel, S. P. (1994). Serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of coexisting depression and psychosis in dementia of the Alzheimer type. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 2(4), 352-354.

- Carlsson, A. R. V. I. D., Bedard, P., Lindqvist, M., & Magnusson, T. (1972). The influence of nerve-impulse flow on the synthesis and metabolism of 5-hydroxytryptamine in the central nervous system. In Biochemical Society symposium (No. 36, p. 17).

- Charney, D. S., Heninger, G. R., Sternberg, D. E., Hafstad, K. M., Giddings, S., & Landis, D. H. (1982). Adrenergic receptor sensitivity in depression: effects of clonidine in depressed patients and healthy subjects. Archives of General Psychiatry, 39(3), 290-294.

- Clarke, D. E., Ko, J. Y., Kuhl, E. A., van Reekum, R., Salvador, R., & Marin, R. S. (2011). Are the available apathy measures reliable and valid? A review of the psychometric evidence. Journal of psychosomatic research, 70(1), 73-97.

- Cooper, C., Lodwick, R., Walters, K., Raine, R., Manthorpe, J., Iliffe, S., & Petersen, I. (2017). Inequalities in receipt of mental and physical healthcare in people with dementia in the UK. Age and ageing, 46(3), 393-400.

- d'Amelio, M., Cavallucci, V., Middei, S., Marchetti, C., Pacioni, S., Ferri, A., ... & Moreno, S. (2011). Caspase-3 triggers early synaptic dysfunction in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature neuroscience, 14(1), 69.

- De Marco, M., & Venneri, A. (2018). Volume and connectivity of the ventral tegmental area are linked to neurocognitive signatures of Alzheimer’s disease in humans. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 63(1), 167-180.

- De Marco, M., & Venneri, A. (2018). Volume and connectivity of the ventral tegmental area are linked to neurocognitive signatures of Alzheimer’s disease in humans. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 63(1), 167-180.

- den Ouden, H. E., Daw, N. D., Fernandez, G., Elshout, J. A., Rijpkema, M., Hoogman, M., ... & Cools, R. (2013). Dissociable effects of dopamine and serotonin on reversal learning. Neuron, 80(4), 1090-1100.

- Dombrovski, A. Y., Mulsant, B. H., Ferrell, R. E., Lotrich, F. E., Rosen, J. I., Lotz, M., ... & Pollock, B. G. (2010). Serotonin transporter triallelic genotype and response to citalopram and risperidone in dementia with behavioral symptoms. International clinical psychopharmacology, 25(1), 37.

- Engelborghs, S., Vloeberghs, E., Le Bastard, N., Van Buggenhout, M., Mariën, P., Somers, N., ... & De Deyn, P. P. (2008). The dopaminergic neurotransmitter system is associated with aggression and agitation in frontotemporal dementia. Neurochemistry international, 52(6), 1052-1060.

- Esposito, Z., Belli, L., Toniolo, S., Sancesario, G., Bianconi, C., & Martorana, A. (2013). Amyloid β, glutamate, excitotoxicity in Alzheimer's disease: are we on the right track?. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics, 19(8), 549-555.

- Flik, G., Folgering, J. H., Cremers, T. I., Westerink, B. H., & Dremencov, E. (2015). Interaction between brain histamine and serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine systems: in vivo microdialysis and electrophysiology study. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, 56(2), 320-328.

- Förstl, H., Burns, A., Levy, R., & Cairns, N. (1994). Neuropathological correlates of psychotic phenomena in confirmed Alzheimer's disease. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 165(1), 53-59.

- Garcia-Alloza, M., Tsang, S. W., Gil-Bea, F. J., Francis, P. T., Lai, M. K., Marcos, B., ... & Ramirez, M. J. (2006). Involvement of the GABAergic system in depressive symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of aging, 27(8), 1110-1117.

- Geracioti Jr, T. D., Baker, D. G., Ekhator, N. N., West, S. A., Hill, K. K., Bruce, A. B., ... & Kasckow, J. W. (2001). CSF norepinephrine concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(8), 1227-1230.

- Gerra, G., Avanzini, P., Zaimovic, A., Fertonani, G., Caccavari, R., Delsignore, R., ... & Brambilla, F. (1996). Neurotransmitter and endocrine modulation of aggressive behavior and its components in normal humans. Behavioural brain research, 81(1-2), 19-24.

- Grosios, K., Gahan, P. B., & Burbidge, J. (2010). Overview of healthcare in the UK. EPMA Journal, 1(4), 529-534.

- Guzmán-Ramos, K., Moreno-Castilla, P., Castro-Cruz, M., McGaugh, J. L., Martínez-Coria, H., LaFerla, F. M., & Bermúdez-Rattoni, F. (2012). Restoration of dopamine release deficits during object recognition memory acquisition attenuates cognitive impairment in a triple transgenic mice model of Alzheimer's disease. Learning & memory, 19(10), 453-460.

- Herrmann, N., Lanctôt, K. L., & Khan, L. R. (2004). The role of norepinephrine in the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 16(3), 261-276.

- Himeno E., Ohyagi Y., Ma L., Nakamura N., Miyoshi K., Sakae N., et al. (2011). Apomorphine treatment in Alzheimer mice promoting amyloid-β degradation. Ann. Neurol. 69, 248–256 10.1002/ana.22319

- Himeno, E., Ohyagi, Y., Ma, L., Nakamura, N., Miyoshi, K., Sakae, N., ... & Tabira, T. (2011). Apomorphine treatment in Alzheimer mice promoting amyloid‐β degradation. Annals of neurology, 69(2), 248-256.

- Holmes, C., Smith, H., Ganderton, R., Arranz, M., Collier, D., Powell, J., & Lovestone, S. (2001). Psychosis and aggression in Alzheimer's disease: the effect of dopamine receptor gene variation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 71(6), 777-779.

- Hoogendijk, W. J., Feenstra, M. G., Botterblom, M. H., Gilhuis, J., Sommer, I. E., Kamphorst, W., ... & Swaab, D. F. (1999). Increased activity of surviving locus ceruleus neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society, 45(1), 82-91.

- Horvath, J., Burkhard, P. R., Herrmann, F. R., Bouras, C., & Kövari, E. (2014). Neuropathology of parkinsonism in patients with pure Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 39(1), 115-120.

- Jobski, K., Höfer, J., Hoffmann, F., & Bachmann, C. (2017). Use of psychotropic drugs in patients with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 135(1), 8-28.

- Kertesz, A., Morlog, D., Light, M., Blair, M., Davidson, W., Jesso, S., & Brashear, R. (2008). Galantamine in frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders, 25(2), 178-185.

- Klein, M. O., Battagello, D. S., Cardoso, A. R., Hauser, D. N., Bittencourt, J. C., & Correa, R. G. (2019). Dopamine: functions, signaling, and association with neurological diseases. Cellular and molecular neurobiology, 39(1), 31-59.

- Koch, G., Di Lorenzo, F., Bonnì, S., Giacobbe, V., Bozzali, M., Caltagirone, C., & Martorana, A. (2014). Dopaminergic modulation of cortical plasticity in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(11), 2654-2661.

- Langballe, E. M., Engdahl, B., Nordeng, H., Ballard, C., Aarsland, D., & Selbæk, G. (2014). Short-and long-term mortality risk associated with the use of antipsychotics among 26,940 dementia outpatients: a population-based study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(4), 321-331.

- Li, Z., Chalazonitis, A., Huang, Y. Y., Mann, J. J., Margolis, K. G., Yang, Q. M., ... & Gershon, M. D. (2011). Essential roles of enteric neuronal serotonin in gastrointestinal motility and the development/survival of enteric dopaminergic neurons. Journal of Neuroscience, 31(24), 8998-9009.

- Lowe, V. J., Kemp, B. J., Jack, C. R., Senjem, M., Weigand, S., Shiung, M., ... & Petersen, R. C. (2009). Comparison of 18F-FDG and PiB PET in cognitive impairment. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 50(6), 878-886.

- Martorana, A., Di Lorenzo, F., Esposito, Z., Giudice, T. L., Bernardi, G., Caltagirone, C., & Koch, G. (2013). Dopamine D2-agonist Rotigotine effects on cortical excitability and central cholinergic transmission in Alzheimer's disease patients. Neuropharmacology, 64, 108-113.

- Matthews, K. L., Chen, C. P. H., Esiri, M. M., Keene, J., Minger, S. L., & Francis, P. T. (2002). Noradrenergic changes, aggressive behavior, and cognition in patients with dementia. Biological psychiatry, 51(5), 407-416.

- McManus, D. Q., Arvanitis, L. A., & Kowalcyk, B. B. (1999). Quetiapine, a novel antipsychotic: experience in elderly patients with psychotic disorders. The Journal of clinical psychiatry.

- Messiah, S. E., Vidot, D. C., Spadola, C., Joel, S., Dao, S., Daunert, S., ... & de la Cruz-Muñoz, N. (2020). Self-Reported Depression and Duodenal Cortisol Biomarkers Are Related to Weight Loss in Young Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Patients. Bariatric Surgical Practice and Patient Care.