Mental Health Factors in Young People

Introduction

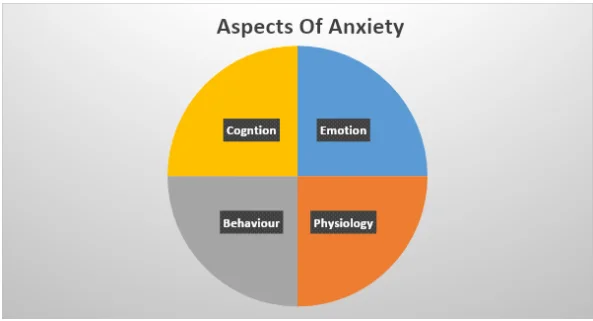

A sense of wellbeing or mental health in young people is not continual, however, responses to the wider contexts, such as, family, personal relationships, friends, school, communities and society of where they live often changes, social media, changes to education curriculum/exams, violence, confusion about sexuality, culture identity, fear for the future and peer pressures, can all have negative impacts on a young person’s mental health and wellbeing (Caldwell et al, 2019). Young people have a better capacity to develop and flourish if they have good mental health. However, if the young person is disadvantaged, suffering poverty, difficult life events such as; bullying, physical, sexual or emotional abuse, disability, sexual identity, these can impact a young person’s mental health and wellbeing, thus, affecting their ability to reach their full potential in future adult life, rates of mental health problems in children increase as they reach adolescence (Sweeting et al, 2010). It is usual to be very nervous the first few days starting a new secondary school, college or employment, so for a young person to show upsetting signs of anxiety is normal and it will usually resolve itself, however, if the anxiety last longer than a few weeks, months, it may be time to seek help. To be diagnosed with the anxiety disorder, the young person must have been suffering for more than 6 months. Recurrent symptoms of anxiety disproportionate to the eliciting outcome are what characterize anxiety disorders. These are the most common disorders among the UK youth (Poppleton et al, 2019). Anxiety generally refers to the physiological state of apprehension, unease or fear in the face of a certain upcoming event or outcome (Poppleton et al, 2019). The most common types of anxiety in adolescence are: generalized, emotional, separation anxiety, social phobia and specific phobias. The victims can have more than one diagnosed at the same time. Therefore, in order to build on data comparison, this paper will refer to all these types of anxiety as ‘anxiety’, unless stated specifically.

Anxiety symptoms can manifest in a number of ways; excessive worry about academic assignments, performance in school, behavioral problems in class, friendships, extreme discomfort in doing something embarrassing in front of others, performing group tasks or eating lunch, negative thinking of self and body image , mood swings, anger, behavioral issues, panic, fear, needing constant reassurance from peers, asking repeated questions, overly talkative, unable to make rational decisions, refusal to socialize and withdrawing all together from social situations, school and friends. Other symptoms include, panic attacks, heart palpitations, high blood pressure, sweating profusely, uncontrollable body-hand tremors, dry mouth, a constant need to go to the toilet (particularly when out in public places), low self-esteem, sleep disturbance and obsessive behavior.

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

This paper foundationally aims to analyze the rise in youth anxiety in the UK (age groups 11-19)

In achieving its main aim, the study has the following specific objectives:

To explore the underlying concept behind anxiety, its prevalence, course and risk factors so that the reasons behind its rise can be understood.

To analyse evidence and reviews on anxiety disorders among the youth, diagnoses, signs and symptoms and treatments in place.

To provide a detailed insight into the causes, types of anxiety disorders and different management strategies in the UK for the different anxiety disorders in young people within both the wider community and primary care settings.

BACKGROUND

Anxiety disorders in the UK have become more common in young people, 1 in 6 are affected, up from 3.9% in 2004, to 5.8% by 2017 (Caldwell et al, 2019). This research paper aims to explore, why youth anxiety is on the rise in the UK? Recent NHS studies, (Moller et al, 2019), many newspaper articles, (Booth, 2019), report that, children and young people’s anxiety rates are on the rise in the UK, therefore, this paper will focus on the anxiety rise within the UK, for (11-19 years). According to Murphy and Fonagy (2013) there is a widespread perception that children and young people today are more troubled than previous generations (Murphy and Fonagy, 2013). Increased levels of low wellbeing in young people have also been found by other reports published in 2018 (Moller et al, 2019) Whilst this paper will focus on the rise of youth anxiety disorders in the UK, it is worth mentioning that, in all age groups within the UK and the majority of European countries, anxiety ranks the highest out of all other diagnosed mental illness, some other EU countries scoring higher than the UK. Globally, anxiety is the ninth leading cause for adolescents (15–19 years), (Caldwell et al, 2019) and ranks the highest mental illness across most nations. This demonstrates that this is not only a problem in the UK, but the world at large. Half of all psychiatric disorders start by age 14 and three quarters by age 18, most cases are not detected or diagnosed, this can have a devastating impact on the young person’s health and wellbeing, extending such effects into adulthood, limiting opportunities that leads to a happy, productive, and rewarding future (Pickering et al, 2019). Many socioeconomic detriments have been established in research studies and books already, therefore for in this paper will build on existing research and analyze what societal changes have happened over the last 10 years in the UK that may have exasperated young people’s mental health. The single largest cause of disability in the UK is dependent on mental health. In terms of causing disability, mental health is a bigger problem than both cancer and cardiovascular disease. (Children Society, 2020). General surveys published in 2018 found increased levels of low wellbeing in young people in the UK. However, it has not been possible before now to establish the trend in underlying rates of mental disorder in young people (Mollar et al, 2019). Anxiety disorders have become more common in young people up from 3.9% in 2004, to 5.8% by 2017. The data reveals a significant increase in emotional disorder for 11 to 19 year olds, whilst other disorder types were stable. Furthermore, childhood and adolescence can be regarded as the core risk phase for the development of syndromes and symptoms associated with anxiety; these may range from mild transient symptoms to full blown anxiety disorders (Beesdo et al, 2009). This state of mind refers to the response by the brain to stimuli that an organism actively tries to avoid or danger. This basic emotion is usually already present in children and the youth, only that these expressions fall on a continuum from mild to severe. A range of studies continually provide persuasive evidence on anxiety disorders and their prevalence in children and the youth (Beesdo et al, 2009). In spite of notable variation in estimates developed regarding the prevalence of any anxiety disorders in studies; which is often because of the method variance;, the prevalence in lifetime in adolescents is about 15-20% (Beesdo et al, 2009). The lifetime estimates are considerably higher than period prevalence estimates. From this fact, it can be noted that anxiety disorders exhibit persisting courses and high rates of forgetting occur for the remitted disorders.

Among children and adolescents, the most frequent disorders are separation of anxiety disorder; with 2.8% and 8% estimates; and social phobias and specific phobias, with respective rates of around 7% and 10%. In adolescents, higher prevalence rates of panic disorders and agoraphobia can be noted (3-4% for agoraphobia, 2-3% for panic); these are usually lower in children. There are always high concerns on the diagnosis of agoraphobia. Even though some studies find high rates of agoraphobia in the absence of panic attacks, other epidemiological studies suggest that there is diagnostic inaccuracies involved (Beesdo et al, 2009). In addition to the rates already presented, the lifetime prevalence of anxiety in adolescents with chronic conditions can even be as high as 40% (Pao and Bosk, 2011; Roy-Byrne et al, 2008). These rates are even higher compared to the general adult population. Several studies have also suggested an increasing number of anxiety symptoms with relation to the severity of medically unexplained physical symptoms (Balazs et al, 2018). Some have even suggested the importance of re-conceptualizing the current classification systems. In a random community sample of youth aged 14-16 in Europe, 5.8% were anxious and an additional one-third had current subthreshold anxiety (Balazs et al, 2018). Suicide risk and burden of diseases increased with the increase of these incidences of anxiety. The concept of self-rated health continuously gains a growing interest, and not only in the UK. This concept, associated with physical, social and mental components, presents an area that is suitable for research (Gore et al, 2011). The problem of the rising trend of anxiety among the youth in the UK has been clearly depicted in various literature. Thus, this research chose to expound on the views, evidence and reviews already done, and try and establish best recommendations in regards to the mental wellbeing of the youth in the UK. It is additionally interesting to look at the modest correlation that exists between self-rated health and clinical assessments on anxiety. From a foundational point of view, self-rated health complaints such as headaches, sleeping difficulties, perceived stress and backaches refer to symptoms experienced with individuals with or without clinically defined diagnosis; these have been found to be common among the youth, and especially among girls, as will be discussed in this paper (Friberg et al, 2012).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Anxiety

Beesdo et al (2009) defines anxiety as a stimuli that an individual organism that will try and avoid a certain situation; a response by the brain to danger. Even though these responses are inherently present in infancy and adolescence, they fall on a continuum from being mild to being severe. In the facilitation of avoidance of danger, anxiety is often adaptive depending on the respective scenario. The adaptive aspects of anxiety can be reflected from the strong cross-species parallels, both in the underlying brain circuitry in the engagement of threats and the organism’s response towards these threats (Pine et al, 2009). Beesda et al (2009) further highlights that one established and frequent conceptualization is that the maladaptation of anxiety surfaces where it interferes with basic human functioning; these include associations with avoidance behavior; which most likely occurs in instances when the anxiety is severe, persistent and frequent. In that regard, extensive and persistent degrees of anxiety and avoidance associated with subjective impairment or distress characterize pathological anxiety. The distinction between normal and pathological anxiety may however be difficult among children and the youth; this is because they manifest many anxieties and fears as part of their typical growth and development (Beesda et al, 2009). As a result, developmental differences should always be placed under consideration in the assessment of anxiety in young people. This enables the making of a viable and applicable diagnostic decision. For instance, whereas children aged 5-7 years may manifest fears of specific objects, natural disasters, specific phobias, among many others, adolescents mainly manifest fear of rejection from peers and negative evaluation. According to Balazs et al (2018), anxiety and physical disorders are often comorbid. In the study, an investigation of characteristics of physical disorders, self-rated health, mental well-being and anxiety in the youth has been conducted. Adolescents aged 14-16 years were included and questions prepared that would evaluate self-rated health and physical illnesses. Several other studies have also inferred the co-occurrence of anxiety with chronic physical disorders among the youth (Pao and Bosk, 2011; Roy-Byrne et al, 2008) Caldwell et al (2019) highlights that common mental disorders are the key causes of morbidity in young people. The evidence highlighted suggest the establishment of lifetime trajectories of common mental disorders by mid-adolescence. Additionally, even in the context of under-detection and reporting, the rates of depression and anxiety are high and increasing among the youth and children (Gore et al, 2011; Bor et al, 2014).

Anxiety disorders

According to Creswell et al’s study (2013), anxiety becomes a disorder when it significantly causes interference in the young person’s life and functioning that manifests as; Avoidance: This would constitute refusal to go to school or participate in usual activities, avoiding family gatherings, not wanting to be around cousins or extended family, avoiding all social situations, playing out with friends, going to the cinema or shopping. Anxiety would basically result in the young person avoiding to participate in activities, which in normal occasions, they would participate in. Interference: Developmental challenges pose significant problems for the young person. In this case, they would be unable to complete tasks in school, get upset easily, and ask the school to contact their parents to pick them up, headaches, stomach-aches, nausea, and other similar patterns of symptoms. Even attending appointments, job interviews prove problematic to young sufferers. The social functioning of the individual is greatly affected; things such as learning about the world. These individuals are even disabled from developing their interpersonal relationships with their friends. They find it difficult to learn how to get along with others, plan, negotiate or organize things Distress: The anxiety becomes extremely distressing and troubling to the young person over long periods of time. In this case, the anxiety is not only problematic to the individual person, but it also causes distress for family members, parents and siblings. Anxiety can interfere with family functioning. As a result, they can no longer participate in activities that they would normally participate in together; such to include having family fun activities, family dinner, visiting extended family members, among many others. The classification of anxiety disorders has undergone some recent changes (Creswell et al, 2013). The present version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) includes generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, panic disorder, agoraphobia and social anxiety disorder. Agoraphobia can be classified as a stand-alone diagnosis; in that its occurrences is can no longer be linked to either the absence or presence of panic disorder.

The disorders associated with anxiety are classified and described in diagnostic systems, such as the DSM of the American Psychiatric Association or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) by the World Health Organization (Beesdo et al, 2009). Across all these systems, many of the classified disorders share common clinical features. However, it should be noted that narrowly categorized anxiety disorders such as agoraphobia, panic disorders and sub categories of specific phobias exhibit substantial degrees of phenotypical heterogeneity or diversity. In addition to the information provided by Beesdo et al (2009), Vallance and Fernandez (2018) highlight that even though the presentation of disorders associated with anxiety in the youth and children may share some differences and similarities to adult disorders, they vary significantly depending on the age of the individual. Assessment, diagnosis and treatment should always distinguish anxiety disorders from appropriate development fears as well as drugs that copy anxiety states and other medical conditions (Vallance and Fernandez, 2018). Creswell et al (2013) support the rise in youth anxiety disorders by reiterating that anxiety disorders in the UK are among the most common psychiatric conditions in the youth. Community studies indicate a period prevalence of 9-13% in young people (Essau et al, 2013). These disorders adversely impact educational achievements, leisure activities and family lives and are often concurrently occurring with other mental disorders, depression and behavioral disorders. Increased rates of anxiety are involved, depression in early adulthood, as well as increased numbers of other outcomes in the mental health and lifestyle of the individual youth affected.

Treatment and management of anxiety

According to Bandelow and Michaelis (2015), most patients seeking help in clinical settings suffer from generalized anxiety disorders, agoraphobia and social anxiety disorders. Notably, when the symptoms are transient mild and without any associated impairments in regards to the occupational and social functions, not all anxiety disorders have to be treated. However, when a patient depicts suffering from complications resulting from the disorders and marked distress, treatment is indicated. It is important to include parents in treatment to help young people manage anxiety. If left untreated the long terms effects on the young person and their family as they go into adulthood are felt. They fail to maximize their education to get the best possible job they can get, and there is a higher risk over time that the youth with untreated anxiety develop depression, which may result into them using drugs and alcohol. Bandelow et al (2017) further highlights that anxiety treatment is mostly on an outpatient basis. Hospitalizations is only necessary where the patient exhibits unresponsiveness to standard treatments, suicidality, or relevant comorbidity such as associated substance abuse, personality disorders and major depression. In 2004, Bandelow and Michaelis (2015) state that it was estimated that disorders arising from anxiety cost the European Union in excess of 41 billion Euros. In understanding the paradigm and approach towards conceptualizing and treating anxiety, it is necessary to look at the difference approaches and theories developed. Consequently, this paper analyzes the understanding posed by medical perceptions and compares this understanding to alternative psycho-social understandings of anxiety; the holistic approach.

Biomedical approaches towards anxiety

Several studies, in this light, postulate that mental health issues are medically rooted; in that the disease model can explain these problems. This theory proposes that in the same way that diseases cause physical illnesses, diseases also cause mental health problems. Several studies, in that light, postulate that mental health issues are medically rooted; in that the disease model can explain these problems (Beckett, 2017). The theory proposes that in the same way that diseases cause physical illnesses, diseases also cause mental health problems. In the biomedical model, there are a range of known biomedical explanations that lead to the causation of mental illnesses; such include genetics, substance misuse or neurological problems (Beckett, 2017). For instance, an individual with anxiety may be affected by the change in eating habits, lowered moods, difficulty in sleeping, among others. Other research show that anxiety does have a genetic basis in some but not all cases, anxiety tends to run in families, children with anxious parents are more likely to have anxiety. Some early neurological studies have been done to look at different areas of the brain to find out if the brain of a young person suffering with anxiety differs from that of a normal brain. The studies based on the biomedical model ultimately suggest there are some specific circuits of the brain that may be overactive in young people with anxiety, therefore inferring that more studies over time will allow scientists to develop better medical treatments. It is assumed that due to the fact that mental illnesses revolve around biomedical issues, the treatments should also be based on medication. These biomedical medications include antidepressants in instances of anxiety and depression, and psychosurgery; a leucotomy (Heeramun-Aubeeluck and Lu, 2013).

Holistic approaches towards anxiety

Although the biomedical model has helped a lot in the development of psychiatry, it has been criticized on several fronts (Beckett, 2017). For instance, a common complain involves its medicalization of commonly experienced anomalous sensations: Social anxiety disorder can act as a good example; where the sufferer complains of persistent and marked fear of performance and social situations in which they fear being embarrassed. Is this actually medicalizing ‘shyness’? Alternative theories to mental illnesses such as anxiety argue that mental health problems are not caused by diseases or genetics, instead, they arise from environmental and psychological problems (Laing, 2010). The factors involved take in a wide range of possible causes, including the personality of the individual and stress (Westen et al, 2014). According to Beckett (2017), due to the distinction from biomedical factors, the validity and reliability of diagnoses of mental disorders are doubtable. For instance, in the diagnosis of anxiety or depression, the test is subjective, non-scientific. This basically relies upon the judgment of the doctor, depending on how the patient answers the doctor’s questions. Historically, Beckett (2017) highlights that the authors of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), in regards to the identification of mental health and appropriate treatments, write significantly based on humanistic ideas. For instance, relatively recently, in 1985, homosexuality was removed as a mental illness. In today’s society, it would seem irregular to classify homosexuality as an illness, however, up until the 1980s, practitioners using DSM as a guide viewed it as a mental health illness. This was followed by a range of strands of personality disorders being included, which was an innovative entry. Through evaluating the psychological causes of mental health disorders, mental health disorders are better understood within the contexts of the individuals’ life circumstances. This also enables a more holistic approach to be taken towards the treatment of these disorders (Laing, 2010). For instance, in this study (Lang, 2010), an example was given of a young girl diagnosed with schizophrenia; the young girl complained she was a tennis ball. An in depth and holistic approach revealed that this bizarre statement was more understandable when it was clear that she referred to herself as a tennis ball because of the experiences of abuse in her childhood, which was connected to gulleys and tennis balls. These are the same sentiments reiterated by holistic based studies (Payne, 2015). Treatment and referral data indicate increased demand for specialist mental health interventions over the past decade (Sarginson et al., 2017).

METHODOLOGY

In order to achieve the main aim of the study which is to analyze the rise of youth anxiety in the UK, the researcher had to conduct a critical literature review. The content- based analysis had to be compared to evidence based practice and the outcomes systematically reviewed and discussed in the paper. The paper, therefore, primary adopts a systematic literature review in which a number of articles were searched, identified, retrieved and selected carefully in accordance with the appropriateness of information. This part looks at how data was obtained, the process involved for verification and relevance, and how data was analyzed and extracted to fit the information disseminated in the paper; therefore, this part contains the search strategy, the eligibility criteria, evidence based research and data analysis.

Search strategy

Ultimately, the generation of key words is the first step in a literature search process. This aspect is importance as it provides a fundamental basis for relevance. From the aim and objectives of the research, certain key terms can be generated: anxiety, effects, and youth (11-19). In June 2019, the following databases were systematically searched: Medline, BMC, NCBI, PUBMED, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL). In clinical research, it is crucial to identify and select the most appropriate databases to be used, this is because the recent advances in technology have made the existence of a variety of electronic databases possible (Bettany-Sltikov, 2012).

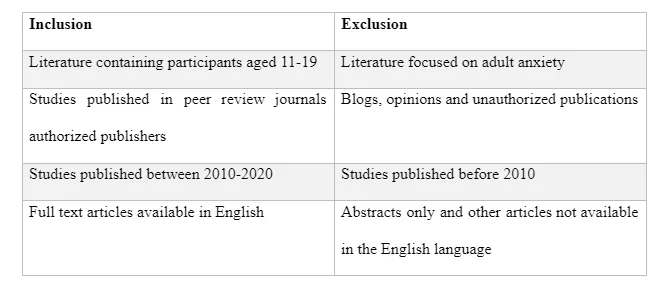

Eligibility criteria

In order to be included in this review, there were certain criteria that had to be fulfilled: the literature had to be relevant to the topic; which looks at anxiety in the UK; the participants in the literature had to be the youth aged 11-19; the studies had to be published in full text available in English and in peer-reviewed journals or books; the published and peer reviewed journals and articles also have to contain recent information in regards to the topic. The studies that were excluded either crossed the age range boundary of participants, measured other irrelevant data; such as focus on depression and other mental illnesses, rather than anxiety; and those that have been outdated; particularly research conducted before 2010. Evidently, non-peer reviewed journals and unpublished articles were also excluded from the research. The criteria has be summarized below.

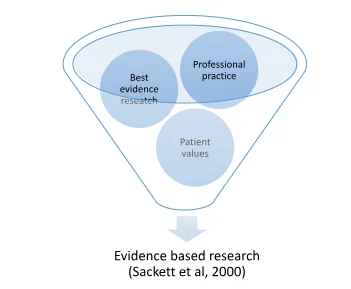

Evidence based research

The topic selected and problem analyzed necessitate practical relevance. In order to improve efficiency and validity, it was necessary to concentrate on literature that would produce much more analytical and practical information, rather than information on the general clinical nature of implementation and theories in practice associated with how anxiety is diagnosed, identified and treated or managed. Evidence based practice basically integrates the aspect of patient values within clinical practice (Sackett et al, 2000). Through such practice, effective relationships between the values of the patient and professional practice can be portrayed.

Data analysis

The measures of the outcomes varied across various studies found. As a result, this paper borrowed a narrative synthesis of the findings. A narrative analysis enabled the confounding, mediation and moderation of variables; and subsequent explanation in the form of appropriate information; just as can be seen in the paper (Keles et al, 2019). The studies used in the paper were systematically followed, described and compounded by comparative synthesis and analysis.

DISCUSSSION

On reviewing Major surveys of the mental health of children and young people in England, surveys were carried out in 1999, 2004, and 2017, four key themes emerged from the data showing the highest increases in anxiety type disorders, for ages 11-19. The increase since 2004 in anxiety is evident in both boys and girls (Bandelow and Michaelis, 2015).

Anxiety disorders in adolescents

According to Siegel and Dickstein (2012), the most important health issues facing adolescents today arise from anxiety disorders. Even though they have high prevalence rates, anxiety disorders are the most undertreated mental health problems in adolescents; recent data suggest only 18% of all anxiety disorders among adolescents are treated (Merikangas et al, 2011). All anxiety disorders share common features at their basic level; these include excessive fear, anticipation, worry in regards to what is to be encountered, avoidance of whatever is feared. Adolescence is an extended period of change. The move to secondary school coincides with the start of adolescence. Anxiety disorders are the most common type at this age, present in 9.0% of 11 to 16 year olds. Among 11 to 16 year olds, boys and girls were equally likely to have a disorder. Girls were more likely than boys to have an emotional disorder (10.9% compared to 7.1%), while boys were more likely than girls to have a behavioral disorder, both explained in the anxiety group of disorders.

Youth suffering from other physical disorders

In accordance with Balazs et al’s study (2013), which investigated the characteristics of self-rated health, physical disorders, subjective well-being and anxiety in adolescents, levels of anxiety were significantly higher in adolescents with reports of physical disability, chronic conditions, impairments associated with health conditions and poor levels of self-rated health (p 0.001, Cohen’s d= 0.40; p 0.001, Cohen’s d=0.40; p 0.001, Cohen’s d=1.11; Respectively). Although the mediational analyses depicted no direct effects by physical disability/ chronic illnesses on the subjective well-being of the youth, indirect effects were evident from the significant high levels of anxiety shown. Csupak et al (2018) amplify this finding in their study where they sought to establish the prevalence of anxiety disorders among people with chronic pain conditions, for example arthritis, migraines and back pains; and comorbidity associated with greater severity of pain. In adolescents and the youth, the most common physical illnesses include diabetes, epilepsy, asthma, burns and aches. The most occurring physical symptoms that cannot be explained medically include general pains, stomachaches and headaches (Pao and Bosk, 2011). Research depicts that the prevalence rates of anxiety disorders are very high in the youth with physical illnesses. In support of this finding, Jones et al (2017), conducted a longitudinal study of up to more than 5000 youth. The baseline of the youth having any chronic physical health condition or who had experienced a chronic physical health condition was 28.6%. Having a physical condition predicted high levels of anxiety or risks thereof. The connection between physical illnesses and anxiety disorders can be both causal or/and synergic; both of these complex in nature (Balazs et al, 2018).

Anxiety disorders in adolescent girls

Young women have been identified as a high risk group in relation to mental health. The survey found rates of emotional mental disorder and self-harm were higher in this group than other demographic groups. Half (52.7%) of young women with a disorder reported having self-harmed or made a suicide attempt of these girls one in three (34.0%) suffer with emotional disorders. Similarly, the findings of Pickering et al (2019) show that whereas there low peer acceptance was significantly relatable to increased social anxiety in both girls and boys, the risk factors that could directly be highlighted to be specific to girls was negative friendship experiences, relational victimization and limited close friendships. In the review, it was suggested that it would be necessary to capture gender-specific and generic risks associated with social anxiety in adolescents. This would be crucial in the development of better interventions and prevention methods that would support girls who are at increased risk of anxiety disorders.

Bullying

Bullying rates worryingly high/ connected to suicide even in anxiety sufferers. 11 to 19 year olds with a mental disorder were nearly twice as likely to have been bullied in the past year (59.1%) as those without a disorder (32.7%). This also refers to cyberbullying. Young people with a mental disorder were also more likely to report having cyberbullied others (14.6%) than those without a mental disorder (6.9%).

LBGT Community.

Associations with mental disorder, young people who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or with another sexual identity were more likely to have anxiety (34.9%) than those who identified as heterosexual (13.2%). Reviews have shown that poor levels of mental health can be seen in lesbians, gays and trans (LGBT) people; this is typically because they are often linked to homophobic experiences and transphobic bullying and discrimination. Other factors which may be related to anxiety disorders prevalent to LGBT include complications arising from age, race and ethnic discriminations.

Social Media and anxiety

Social media has been used to refer to the interconnection of various internet-based networks, visually and verbally. According to the Pew Research Center (2015), around 90% of teenagers are active on social media. Additionally, more than half of adolescents use a smart phone in the modern society; those aged 15 to 17. Social media can be blamed for the increasing number of mental health problems in young people. This is concurrent to the fact that social medial is continually becoming inextricable to our daily lives (Keles et al, 2019). Due to the simultaneous mental health problems associated with social media, understanding the impact of social media on adolescents’ well-being has become a priority. The problematic behaviors associated with the use of the internet are often described in psychiatric terminology, an example is ‘addiction’. The influence of social media on anxiety disorders among the youth can be analyzed in four domains: time spent, the activity, investment in the activity and addiction. Keles et al (2019) established the fact that all these domains directly correlated with anxiety disorders. Some activities by young individuals may be misconstrued to be abnormal. For instance, according to McCrae (2018), the youth engaging in social media may frequently post images of themselves; this may appear narcissistic, but in actuality, it is a social norm in younger social networks. In the same regard, young people aged 11-17 years often find themselves comparing themselves to others. Psychologists and other experts have often warned on the engagement of the youth with social media and the related impairments to social and personal development (Greenfield, 2014)

Consequences of undiagnosed and untreated anxiety disorders

Goodman et al (2011) highlight the fact that untreated anxiety can have distressful impacts on income, relationship stabilities and employment. This is an aspect that is clearly brought out in vast number of other studies (Beesdo et al, 2009; Poppleton et al, 2019; Bandelow et al, 2017). Anxiety disorders lead to significant interferences with the everyday functioning of young people. These range from school performance, functioning in a social setting, sleep and leisure activities (Hill et al, 2016). The following are some of the effects that can be associated with anxiety disorders. Truancy: Children with a disorder were more likely to play truant (8.5%) than children without a disorder (0.8%). Truancy rates varied by type of disorder, and were highest in those with an emotional (9.7%) or a behavioral (11.2%) disorder (Bandelow and Michaelis, 2015). Exclusion from school: School exclusion more common among the youth with anxiety disorders (6.8%) than in those without (0.5%). Boys with a disorder (9.9%) were more likely than girls with a disorder (2.4%) to be excluded from school (Mental Health Foundation, 2014). As a result of truancy and exclusion from school, together with the general disruption of school activities, individuals suffering from anxiety disorders are also likely to attract poor learning outcomes, low levels of learning and low grades. Decreased social development levels: Hill et al (2016), in causing significant interference with the day-to-day functionality of the individual, anxiety disorders greatly impact the social functioning of the youth. According to Hagell et al (2013), anxiety disorders have important and significant implications upon every aspect of the young man’s life; this includes the ability to engage with friends; social interaction and development; ability to build on constructive family relationships and the ability to self-realize themselves; which includes the aspect of progressing and looking for employment. It is important to note that if anxiety disorders are left untreated, they could often persist into adulthood or run a chronic course into adulthood. Hill et al (2016) depicts the nature of the long term health problems in adulthood. Siegel and Dickstein (2012) found that anxiety disorders that were common during childhood and adolescence were strongly predictive in their young adulthood. The study highlights that the fact that anxiety disorders typically occur concurrently, and are often comorbid with other conditions; such as depression; the development of other serious mental health problems in later life can be expected. The risks entail a wide range of actions and issues; such as severe depressive disorders, substance misuse and abuse, and even the risk of suicide. Long term anxiety can generally be severe in terms of its effects to the personal development and education of the youth affected.

Factors contributing to poor mental health outcomes of young people

Social and family factors

According to the Mental Health Foundation (2014), anxiety caused by social relationships and families featured prominently. 26% of participants revealed personal relationships to be the cause of day to day anxiety feelings; this especially related to students and the youth. A number of participants also identified the welfare of children, family members and loved ones as causes of anxiety. Another interesting anomaly presented in the study was anxiety due to the fear of being alone. The youth were twice as likely to be affected by this factor compared to older people. Consequently, it may be evidently inferred that there is ultimate importance placed on a sense of belonging to a peer group by the young people. Additionally, since the 1960s, a typical nuclear family had the father as the breadwinner, the mother as the stay-at-home wife and the biologically related children (Sweeting et al, 2010). However, this gradually and continually changed over the years, with National Statistics (2009) recently pointing out the rise in proportions of families with dependent children headed by lone parents from 13% in 1987 to 25% in 2006. Although maternal employment does not appear to have a direct effect on the adolescent’s mental well-being, reviews suggest that in a typical family structure, divorced families tend to produce poorer self-conceptualization, social competence and mixed effects. Moreover, adolescent anxiety disorders have also been associated with parent anxiety disorders; children and adolescents whose parents have anxiety disorders are more likely to also get anxiety disorders.

Economic Factors

Anxiety disorders may be greatly affected and explained by the socioeconomic status and factors in the economy such as unemployment. The evidence depicted is based on the differences in mental health according to the economic conditions of families, or individuals associated with the families (Sweeting et al, 2010). Even though the overall economic conditions within the UK have been improved form the 1980s to the modern times, the difference in levels of anxiety can be evidently witnessed with the difference in economic statuses. There are many other environmental and psychological risk factors which may differentiate between anxiety disorders in adolescences and normal fears. Other factors include risky behaviors such as drug and substance abuse, and difficulty in peer relationships, which may however be associated with subsequent anxiety in adolescents (Siegel et al, 2009). There is also the aspect of behavioral inhibition, which is a temperamental characteristic that refers to the trait that causes the inhibition of high levels of fear in response to certain situations. This aspect is associated with anxiety disorders in later childhood and adolescence (Siegel and Dickstein, 2011).

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

According to Caldwell et al (2019), the rates of depression and anxiety are increasing becoming significant among the youth in the UK. Although recent policies put in place have tried to focus on primary control and management of mental health issues in the youth and their school settings, there is limited information available on the comparative effectiveness of the multiple interventions available. The idea brought out in this review is however significantly important, the control and management of youth anxiety should primarily be battled in schools and other educational settings. Schools should be at the forefront of implementation of strategies and plans that would effectively focus on management of youth anxiety. Psychopharmacotherapy for young people has been debatable to many researchers (Dubicka and Wilkinson, 2018); the capacities of children and adolescent services that focus on mental health are also under-resourced worldwide (Rocha et al, 2015). Furthermore, Caldwell et al (2019) has highlighted that even with optimal health care access and treatment, more than 70% of the burden associated with mental disorders could not be alleviated. In spite of the significant public health burden associated with children and young people with anxiety disorders, they often remain untreated. The considerations recommended collectively amplify the importance of early access to effective treatment and management. In that regard, primary prevention of common mental disorders such as anxiety is a growing imperative to certain institutions; these include educational settings (McLaughlin, 2017). This paper also foundationally supports the study by Beckett (2017), which proposes that understanding alternative perspectives in mental health in regards to the diagnosis and treatment of mental health disorders is important. It is only through clearly and correctly understanding the cause of specific disorders that the social worker may know and distinguish whether there is biomedical aetiology, or psychiatric input. This also enables the social worker to be aware of whether or not the disorder was as a result of environmental factors, which might be malleable to the input made by the social worker. The aetiology of anxiety disorders may encompass complex environmental and genetic influences. It is through research and close analysis that additional insight into the causation can be provided (Vallance and Fernandez, 2018). It is therefore vital to seek and consider each and every possible cause involved and consequently, appropriately take steps towards mitigation and treatment of the individuals affected. In that regard, Vallance and Fernandez (2018) reiterate that in regards to treatment and management, it is necessary to find out the most appropriate intervention during diagnosis; assessment enables compassing of both psychoactive medication and psychological therapies. Regardless, given the commonality, prevalence, and damaging nature of youth anxiety in the UK, it is important to ensure that these disorders are promptly diagnosed and accordingly managed using evidence-based treatments (Hill et al, 2016).

REFERENCES

Balazs, J., Miklosi, M., Kereszteny, A., Hoven, C., Carli, V., Wasserman, C., Apter, A., Bobes, J., Brunner, R., Cosman, D., Cotter, P., Haring, C., Iosue, M., Kaess, M., Kahn, J., Keeley, H., Marusic, D., Postuvan, V., Resch, F., Saiz, P., Sisask, M., Snir, A., Tubiana, A., Varnik, A., Sarchiapone, M., Wasserman, D. (2013). Adolescent subthreshold-depression and anxiety: psychopathology, functional impairment and increased suicide risk. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 54(6), 670-677

Bandelow, B. Michaelis, S. (2015). Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci, 17(3), 327-35

Beckett, J. (2017). Evaluating some of the approaches: Biomedical Versus Alternative Perspectives in Understanding Mental Health. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders, 1(2)

Beesdo, K., Knappe, S., Pine, D. (2009). Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Developmental Issues and Implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am, 32(3), 483-524

Bor, W., Dean, A., Najman, J., Hayatbakhsh, R. (2014). Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry,48, 606-616

Caldwell, D., Davies, S., Hetrick, S., Palmer, C., Caro, P., Lopez, J., Gunnell, P., Kidger, J., Thomas, J., French, C., Stockings, E., Campbell, R., Welton, N. (2019). School- based interventions to prevent anxiety and depression in children and young people: a systematic review and network meta- analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry¸6 (12), 1011-1020

Csupak, B, Sommer, J., Jacobsohn, E., El-Gabalawy, R. (2018). A population-based examination of the co-occurrence and functional correlates of chronic pain and generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord, 56, 74-80

Essau, C., Ollendick, T., Essau, C., Gabbidon, J. (2013). Epidemiology, comorbidity and mental health service utilization. The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of the treatment of childhood and adolescent anxiety. 1, 23-42

Gore, F., Bloem, J., Patton, G., Ferguson, J., Joseph, V., Coffey, C., Sawyer, S., Mathers, C. (2011). Global burden of disease in young people aged 10-24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet, 377(9783), 2093-102

Heeramun-Aubeeluck, A., Lu, Z. (2013). Neurosurgery for mental disorders: a review: review. African Journal of Psychiatry, 16:177-181

Jones, L., Mrug, S., Elliot, M., Toomey, S., Tortolero, S., Schuster, M. (2017). Chronic Physical Health Conditions and Emotional Problems From Early Adolescence Through Mid-adolescence. Acad Pediatr, 17(6), 649-655

McLaughlin, C. (2017). International approaches to school-based mental health: intent of the special issue. Sch Psychol Int., 38,339-342

Merikangas, K., He, J., Burstein, M., Swendsen, J., Avenevoli, S., Case, B., Georgiades, K., Heaton, L., Swanson, S., Olfson, M. (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S adolesents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey- Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 50(1), 32-45

Murphy, M., Fonagy, P. (2013). Mental health problems in children and young people. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2012

Pine, D., Helfinstein, S., Bar- Haim, Y., Nelson, E., Fox, N. (2009). Challenges in developing novel treatments for childhood disorders: lessons from research on anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology, 34(1), 213-28

Rocha, T., Graeff-Martins, A., Kieling, C., Rohde, L. (2015). Provision of mental healthcare for children and adolescents: a worldwide view. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 28, 330-335

Roy-Byrne, P., Davinson, K., Kessler, R., Asmundson, G., Goodwin, R., Kubzansky, L., Lydiard, R., Massie, M., Katon, W., Laden, S., Stein, M. (2008). Anxiety disorders and comorbid medical illness. Gen Hos Psychiatry, 30(3), 208-225

Sackett, L., Strais, E., Richardson, W., Rosenberg, W., Haynes, R. (2000) ‘Evidence- based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM’, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone

Sweeting, H., West, P., Young, R., Der, G. (2010) Can we explain increases in young people’s psychological distress over time? Social Science and Medicine, 71 (10), 1819-1830

Westen, D., Shedler, J., Durrett, C. (2014). Personality diagnoses in adolescence: DSM-IV axis II diagnoses and an empirically derived alternative. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 952-966

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts