The 2009 H1N1 Pandemic and Healthcare Impact

1.0 INTRODUCTION

A new strain of the influenza 1 emerged in the USA and Mexico in 2009; this strain quickly spread worldwide. This outbreak was later declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be a pandemic (Girard et al, 2010). Although this disease was not as severe as anticipated in the UK, the healthcare sector experienced significant pressure in regards to it. This strain of pandemic influenza, though mild in most instances, was severe to a minority; it was even sometimes fatal (Hothersall et al, 2012). From both economic and healthcare standpoints, influenza causes a significant burden all over the world. There is an increased risk of exposure of the disease to healthcare workers (HCW). They remain to be at an increased risk of being exposed to respiratory pathogens compared to the general population (Dini et al, 2017). This is accompanied by the potential threat for their personal health and their patients’ safety. This is the main reason why the UK National Health Service (NHS) recommends annual vaccination against influenza for all staff. According to Nair et al (2012), the number of HCWs who may be infected with flu during a mild flu season amounts to around 23%. Out of this number, 28-59% of them will have subclinical illness. Therefore, HCWs can even be regarded as very important vectors of the disease; they may cause transmission of the disease to the patients. As part of the global response to the pandemic, vaccines were developed. GlaxoSmithKline (Pandemrix) and Baxter (Celvapan) were the two vaccines initially licence in the UK. Baxter involves a two-dose schedule and it is reserved to people in the UK who cannot have GlaxoSmithKline. The former, on the other hand, involves a one-dose schedule for most people (Hothersall et al, 2012). The vaccines proved to have acceptable safety profiles; this applied to all 2009 H1N1 vaccines (Zhu et al, 2009). There was, however, considerable media unease at the time of the pandemic, this was especially about the vaccine’s safe testing in relation to pregnancy (Hothersall et al, 2012). Other controversial factors include the relationship or possible link between the vaccines and Guillan-Barre syndrome, among other rare complications (Laurance, 2009). The general population articulated the concerns with the vaccines. Researchers conducted surveys in relation to the uptake of the vaccines among the populations. Early surveys indicated that, presumably because of the same concerns, the intentions of healthcare workers to be vaccinated was low (Hothersall et al, 2012). The same effects could be seen on a global scale. In other healthcare settings, vaccinating healthcare workers has been depicted to be a cost-effective way of reducing transmission and protecting the most vulnerable in the population (Burls et al, 2006). In order to maintain the frontline medical services offered, frontline healthcare workers have been prioritized from the beginning of the vaccination campaign. This was not only meant to protect them, but also their patients. So many things are prevented because of influenza vaccination of healthcare workers. Some of these include the prevention of seasonal influenza, reduction of absenteeism, and the protection of patients from nosocomial infections, resulting to a decrease in mortality and morbidity (Lee et al, 2012). The vaccination is quite effective in the reduction of influenza-like illnesses, physician visits and working days lost. Only high-risk group are subsidised or offered free vaccination services in many countries (Yeung et al, 2016). Individuals below the age of 65 years and without any chronic diseases are considered part of non-high risk groups. Influenza is a self-limiting and mild disease for most healthy adults. According to the World Health Organization (2012), health authorities in most countries do not consider these people as priority groups that require annual vaccination against influenza. Some countries such as Austria, Estonia and the USA, however, have outlined exceptions, such that in these countries, all people aged 6 months or older should be vaccinated against influenza (Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2013).The pandemic in 2009 shifted various perspectives relating to the vaccination of healthy adults. According to statistics, the pandemic increased hospitalization and disproportionately affected adults below the age of 65 (Yeung et al, 2016). Yeng et al (2016) even further highlight that the increasing predominant circulating strain in Europe, China and North America was the influenza A (H1N1) pdm09. In a normal adult, vaccination enables the decrease in work absenteeism, and the unplanned needs for medication and medical visits. Furthermore, most middle-aged adults may have undiagnosed underlying conditions, such as diabetes. Through vaccination, both non-high risk and high-risk groups are protected from influenza, as well as other complications. This enables the moderate protection of every individual, including Healthcare workers (Osterholm et al, 2012). In addition, influenza vaccination of home care staff of the NHS in England have found to reduce morbidity, health service use among residents and mortality (Hayward et al, 2006).

Despite the notable significant benefits of vaccinating healthcare workers against seasonal influenza, the vaccine uptake among the HCW in the UK has been surprisingly low, with some studies depicting an uptake of less than 20% experienced in the year 2008/2009 (Sethi and Pebody, 2011). According to Lee et al (2012), similar low uptake rates have been reported across Europe, many other European countries. This was particularly before the pandemic year. During the pandemic year, the influenza vaccine uptake rates among HCW increased to around 40% in the UK and to around 26.4% from 16.5 across European countries (Sethi and Pebody, 2011). According to research, a strong predictor of both the seasonal and H1N1 vaccine uptake rates is the previous history of seasonal influenza vaccination (Virseda et al, 2010; Glaser et al, 2011). The suboptimal coverage of the vaccination imposes a significant burden to both the economic and healthcare sector worldwide. This coverage has since remained low, even though many have advocated for the primary importance of immunization; it remains to be a fundamental tool for the prevention of influenza (Dini et al, 2017). Dini et al (2017) further highlights that even though this primary objective of immunization has been echoed in most western countries, the last decade has seen inadequate uptake of the flu vaccine among HCW in the UK. Various reviews on the topic have shown that the main drivers towards vaccination include the concern towards protecting the patients, the desire for self-protection, and the desire to protect one’s family. However, HCW who oppose the vaccine raise safety concerns (Dini et al, 2017). These concerns were also backed up by other issues such as negative attitudes towards the vaccine, socio-demographic variables, lack of access to the facilities of vaccination, lack of adequate knowledge concerning influenza, no history of influenza or its vaccination, lack of perceived behavioural control, low social pressure, negative perceptions towards the social benefit associated with influenza vaccination and the perception of low risk (Dini et al, 2017). Even though studies that show the correlation between subsequent seasonal influenza uptake and the H1N1 vaccine uptake are unavailable, after the H1N1 pandemic, figures show that there was an increase in the former (Lee et al, 2012). The achievement of high vaccine uptakes in the early stages of the medical professionals may prove to increase subsequent influenza vaccine uptake (Amodio et al, 2011). In addition, improving the population’s vaccine coverage requires a better understanding of the reasons and perceptions behind people’s choices towards vaccination. There is a current recommendation by the UK Department of Health (DH) that all HCWs who come into contact with clients or patients should be vaccinated against influenza every year (Public Health England, 2016). The policy is however not being enforced. Although not enforced, all community health services and hospital settings have set an aspirational target of 75% coverage of the vaccination. These settings have also been linked to additional funding; winter pressure funds (Kliner et al, 2016). The target set by both the NHS and the Public Department of Health has still not affected the vaccination coverage among the HCWs. These have been estimated to be 50.6% during the 2015/16 year and 54.9% during the 2014/15 year (Kliner et al, 2016). As will be discussed in this dissertation, there are a number of factors associated with the low rates of uptake of the vaccine among HCWs in the UK; the same can also be noted on how the vaccine coverage rates may be increased. Dini et al (2017) admit that the study of the factors that affect influenza vaccine uptake among HCW in the UK may be challenging, and full of ethical issues. Currently, there are even mandatory countries in place in many countries. Studies conducted in a high quality manner will enable stakeholders and policy-makers to shaper evidence-based initiatives, recommendations and programs so that they can improved the control of influenza in the UK. Particular interest will be accorded to the degree of misconceptions regarding the uptake of influenza vaccine by the HCWs explored by various literature. What can be foundationally noted is that various studies and systematic reviews have drawn almost the same body of evidence, but reached different conclusions and discussions; rather than significantly contributing to the best possible position and how influenza may be best controlled among HCWs in the UK.

Looking for further insights on The Global Prevalence and Impact of Ovarian Cancer? Click here.

Therefore, this research sought to look at different rationales and perceptions towards vaccination, summarize them in the form of the best available evidence, conduct a critical appraisal, and review on the evidence collected.

Aims and Objectives

This study aims at determining and analysing the factors affecting the uptake of the influenza vaccine among healthcare workers in the UK.

In achieving this aim, the study has the following objectives:

To analyse the importance of the influenza vaccine in regards to public health and the general population

To analyse the policies and guidelines currently in place in relation to the uptake of the influenza vaccine among HCWs in the UK

To critically appraise and analyse literature on the factors that influence the uptake of influenza vaccine among HCWs in the UK

Research Questions

From the aims and objectives of the dissertation, the following research questions can be formulated. These questions help guide the content of the study.

What is the importance of the influenza vaccine in regards to the general population safety and public health?

What are the uptake rates of the influenza vaccine among HCWs in the UK?

What are the factors that influence these uptake rates among HCWs in the UK?

Which are the best possible practices in regards to influenza vaccine uptake and the control of influenza among HCWs in the UK?

2.0 METHOD

In order to present a systematic plan, a well-structured and outlined research methodology has to be initiated. The researcher has to choose an appropriate technique and method to be used in the study. Two types of methodological research can be highlighted: Primary research and secondary research. Primary research entails the direct collection of data from participants related with the study (Petek and Kamnik-Jug, 2018). Primary research involves the performance of experimental or clinical studies, while secondary research consolidates studies such as meta-analyses, systematic reviews and other kinds of reviews. Primary research has three main areas: epidemiological research, clinical research, and basic medical research (Kapoor, 2016). Epidemiological trials or research may include experimental or observational studies; basic research involves research that is fundamental and may be either theoretical or applied. Figure 1 shows the basic classification of the types of clinical research. Kapoor (2016) adds in almost all studies, the dependent variables are investigated whereas at least one independent variable is varied.

Secondary research involves the collection of information from various sources; mainly through existing literature related to the topic being investigated (Song et al, 2017). In this kind of research methodology, researchers undertake to critically analyze and evaluate information from the selected literature and essentially raise issues that arise from these studies so that they can be effectively resolved. This study uses secondary research methodology in the collection of its data. Secondary research is advantageous in this instance as it allows the efficient collection of data from previous research, all from various valid and credible sources. Primary research, on the other hand, is costly and time-consuming, making it harder to conduct and collect scientifically approved observations and data in due time. According to Moyle et al (2016), the issue that may arise in regards to secondary data is that the information disseminated in the study may be influenced by personal attitudes and beliefs. Therefore, this study adopts a systematic literature review; where data will be systematically and critically analyzed from various selected literature on the topic. A certain number of articles will be systematically searched, identified and conscientiously selected so that the most appropriate and relevant information may be disseminated in the study. Consequently, this part of the dissertation provides for the replication of how the researcher adopts a systematic literature review, and provides for any methodological issues that may arise from the study design adopted. Considering all matters that may arise in the method of research, this section will look at how the researcher arrived at the topic, the aims and objectives, research questions, the generation of key terms and sentences in regards to the topic, the search strategy used, the most appropriate databases selected, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, critical appraisal tool used, the literature selected and search outcomes, how these literature are to be analyzed, relevance of the materials selected and the concept of evidence-based research in relation to the topic selected.

2.1 Research topic

The topic selected for the study is:

Factors that influence the uptake of influenza vaccine among healthcare workers in the UK

The generation of an appropriate research topic is an essential first step in executing a well-structured research. The focus on the topic and the identification of key issues depend on the development of an effective research topic or question. In order to achieve this, the PEO framework in the development of the research topic guided the researcher. According to Amodio et al (2017), this framework enables the researcher to analyze the clinical problem in accordance with the existing conditions. The framework stands for Population (P), Exposure (E), and Outcome (O). The healthcare workers who are at the frontline in delivering care services to sick individuals are the focused on population. The influenza vaccine uptake, being the problem identified by the study, is the exposure. The results of the study will be based on the factors that are associated with the influenza vaccine uptake among healthcare workers in the UK; the results depicted by the study are the outcome. From the framework, therefore, the research question becomes: What are the factors that influence influenza vaccination uptake among healthcare workers in the UK? Table 1 shows the development of the research question based on the PEO framework

From the research question, the researcher has to come up with the most relevant research aim and objectives. Consequently, the researcher may also develop various research questions in a bid to help him achieve the aim of the study. As a result, this study aims at determining and analysing the factors affecting the uptake of the influenza vaccine among healthcare workers in the UK. The objectives and the research questions formulated to help the researcher have been highlighted in the first section.

2.2 Generation of key words

Certain key words are noticeable from the research topic selected. For a successful literature search process, key words have to be generated from the research topic or question. Gu et al (2017) further suggest that key words allow for easier information search from a pool of data; it is therefore essential to first generate the most relevant key words that can be used in the literature search. This is ultimately the first step in the literature search process. This study aims at analysing the factors that influence influenza vaccine uptake among healthcare workers in the UK. The aim of the study was directly siphoned from the research question. From this aim, certain words seem to provide a significant insight to the research questions, these are the key words. The generation of key words is important as it plays a crucial role in obtaining more literature on the topic area. Additionally, the second step within this first step would be the identification of synonyms (Bettany-Saltikov, 2012). This increases sensitivity and the possibility of identifying articles that are more relevant to the research topic or focus. In this study, key words identified by the researcher are ‘influenza vaccine, ‘factors that influence influenza vaccine uptake’, ‘healthcare workers in the UK’, influenza vaccine uptake among healthcare workers’, among many others. Boolean operators refer to the words used to connect or exclude key words during the search. These include ‘OR’ and ‘AND’, they enable the development of a more focused research. They also enable much more productive results. These mainly applied in the use of synonyms. In the generation of key words, it is also necessary to account for the use of synonyms and their variations (Aveyard, 2010). Truncations of words were also necessary so that only relevant articles would be found. Table 2 shows the generation of key words in relation to the PEO framework.

2.3 Literature search

Following the generation of key words, literature search was conducted. In all forms of research, there are a number of electronic databases; this critical review was conducted via these electronic databases. Electronic databases allow the collection of huge amounts of data regarding the research topic from a variety of resources and without much hindrance (Huerta et al, 2016). The conduction of research via electronic databases enables the researcher to present large amounts of narrative information on the topic. This in turn, ensures an in-depth understanding of the topic and presents knowledge that meets the aims, objectives and raised issues in the study. The study uses various electronic databases; these enable the researcher to gather data from various sources and critically compare a variety of information from various geographical locations regarding a single topic. Although the use of electronic databases may be easy and convenient, it can only be made possible if one has the necessary technology skills and knowledge on how to use these databases through library tutorials. It is always crucial to carefully select the most appropriate databases to use in clinical research (Bettany- Sltikov, 2012). In regards to the process, in order to obtain the general outline of what is being investigated, a preliminary search was conducted. This was done through google scholar. Further identification had to be done to increase the efficiency of the literature search process. The concentration on specific databases would produce much more practical and analytical articles on the research topic. In this study, articles and literature selected were derived from the following databases: MEDLINE, Google scholar, BMC, NCBI, PUBMED, BMJ and PMC. These databases were chosen based on their reliability and ability to produce wider and more detailed search, which would in turn significantly help in tackling the research topic.

2.4 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This is basically the criteria used to identify the right characteristics of certain studies so that the researcher may be able to gather definitive information. Budrionis and Bellika (2016) state that the inclusion criteria are basically the characteristics of studies which are acceptable, or are the most appropriate for the study, whereas the exclusion criteria are basically characteristics rejected by the study; this may be because these studies may cause unnecessary errors which compromise the quality of outcome for the research. The study focuses on the factors that influence influenza vaccine uptake among HCWs in the UK. This, being the research topic, should be accompanied by a certain criteria that would help the researcher evaluate and identify the right articles to be used in the study. The study’s inclusion criteria for the articles include fully accessible articles that contain information on the research topic, articles published in the English language; only peer reviewed and published literature and articles published on or after 2013. The exclusion criteria, consequently, includes articles with only abstracts available, articles published in other languages; not English, literature published before 2013, and literature that contain information on factors that influence influenza vaccination uptake in other people, other than HCWs. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of this study has been summarized in table 3 below.

Only articles published in the English language will be included in the study. Articles published in other languages are excluded foundationally because the study has been organized and conducted in the UK, where English is the official language. Using these articles, therefore, would be difficult as both the researchers and the readers may not be able to understand or directly interpret the findings of these studies. This will lead to the presentation of invalid findings or results in the study. In a bid to capture the most current information on the research topic, only articles published on or after 2013 will be reviewed. This criterion allows the analysis and presentation of updated data; therefore avoiding errors that can arise because of using backdated information. Full-text and fully accessible articles will be used as they allow the researcher to deeply understand the presented information, rather than deduce certain concepts from abstract only texts. Abstract-only texts may mislead the researchers into providing inappropriate arguments and evidence that may not be presented in the actual study. Essentially, the inclusion criteria has to involve articles that specifically focus on HCWs in the UK. Therefore, studies that do not look at HCWs; for instance those focusing on normal adults or patients; are disregarded, as they do not fall within the ambit of the research topic. Even though some of the findings and concepts within these studies may be appropriate, presentation of the most appropriate results can be done through articles that are directly relevant to the research topic.

2.5 Critical appraisal

Researchers to help them select the most relevant studies and the most appropriate too, in regards to high quality evidence (Shea et al, 2017) use critical appraisal tools. The CASP tool is used in this study; this Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was used to critically evaluate the articles selected. This tool aids in the evaluation of collected evidence on the research topic, from the selected sources. In clinical research, the CASP tool is also versatile and specific; therefore enabling the effective evaluation of evidence, especially in terms of credibility, reliability and validity. This tool enables the researcher to gather effective, valid, credible and reliable evidence in relation to the factors that affect influenza vaccine uptake among HCWs in the UK. Aveyard (2010) supports that a critical appraisal tool is supposed to guide the researcher in evaluating and facilitating a critical appraisal on the articles identified.

2.6 Data analysis

Data collected from the selected sources have been analysed and the most appropriate themes generated thereafter. The generation of themes in a study enables a systematic presentation of the findings from the literature reviewed and the organised assessment of the issues that may arise in regards to the research topic (Vaismoradi et al, 2016). Themes generally yield more practical results in relation to the field of the study. The fact that nursing is a pragmatic discipline requires that researchers develop and devise practical findings; the thematic depiction of these findings enhances the action the study has on practicability and its impact in nursing (Vaismoradi et al, 2016).

2.7 Evidence based practice

When clinical practice is conducted in an evidence-based manner, patient outcomes are improved (Black et al, 2015). There are a lot more advantages attributed to evidence based practice; Black et al (2015) add that this concept has been shown to improve clinical outcomes, decrease variations in patient outcomes, reduce health care costs and increase patient safety. The advantages of evidence-based practice (EBP) are well substantiated. Reid et al (2017) define this concept as the judicious, explicit and conscientious use of the current evidence in clinical decision making matters. This constitutes the use of the best empirical evidence available for such matters. It integrates the best available clinical evidence from systematic research with individual clinical expertise (Reid et al, 2017). Whereas the importance and full value of EBP has been discussed in a number of studies, nurses and other professionals are still reluctant to embracing EBP with a number of them reporting the lack of knowledge on what the concept constitutes or how it can be implemented (Brown et al, 2009). As a result, professional regulatory bodies such as the United Kingdom’s (UK) Midwifery Council (NMC) have emphasized on EBP teaching within the curricula of nursing undergraduates (Reid et al, 2017). Considering all these, this systematic literature review was conducted with a foundational view of increasing and enhancing EBP. As a fundamental clinical research concept, EBP enhances the practicability, validity and credibility of research.

3.0 RESULTS

In a bid to achieve its aims and objectives, the study conducted a systematic literature review. This part shows the results of the method used in the study, the search outcomes, the literature selected for review, data extraction, and the presentation of the issues or thematic concerns that arose from the review.

3.1 Search outcomes

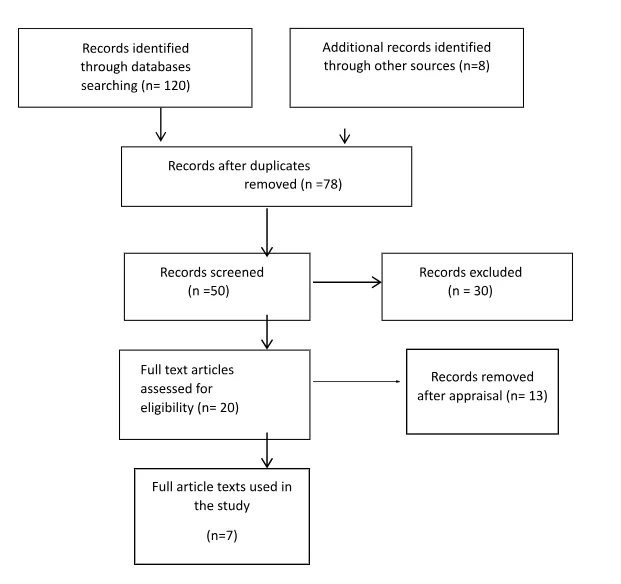

The initial search conducted via google scholar brought back over 120 articles and a variety of other books and literature. From the generation of key words and the development of a search strategy, another search was conducted across all databases. This search produced a total of 50 articles. From the 50 articles, the inclusion and exclusion criteria was applied. Using these criteria, a number of articles were eliminated from the search based on relevance and appropriateness; as a result, a total of 20 articles remained. Further refinement on the search was done, this time using the CASP tool; this was done to critically evaluate the 20 full-text articles available for review based on their reliability, validity and credibility. After this final refinement process, only seven main articles were identified and selected for the review. These were the articles mainly used in the study. The PRISMA diagram provides a detailed summary of the search outcomes.

3.2 Literature selected

After a systematic process of literature search and critical appraisal of the literature retrieved, seven main articles were selected for this review. The pieces of evidence contained within these articles are appropriate and valid as far as the research topic is concerned. These were the literature selected:

Jessop, C., Scrutton, J. and Jinks, A 2017. ‘Improving influenza vaccination uptake among frontline healthcare workers’, Journal of Infection Prevention, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 248-251. doi: 10.1177/1757177417693677

Mounier-Jack, S., Bell, S., Chantler, T., Edwards, A., Yarwood, J., Gilbert, D. and Paterson, P 2020. ‘Organisational factors affecting performance in delivering influenza vaccination to staff in NHS Acute Hospital Trusts in England: A qualitative study’, Vaccine, vol. 30, no. 15, pp. 3079-3085. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.02.077

Rogers, C., Bahr, K., Benjamin, S 2018. ‘Attitudes and barriers associated with seasonal influenza vaccination uptake among public health students; a cross-sectional survey’, BMC Public Health, vol. 18, no. 1131

3.3 Data Extraction

Depending on the type of research, there are several ways of extracting and synthesizing data in research. This is a systematic literature review, and as such, data extraction was systematically done. The data extraction from the literature selected entailed the following: the author and year of the studies, the main aim of the studies, the methodological design and the main findings of the studies. This was done according to Timmins and McCabe (2005). Appendix 1 provides for a summary of these. The study gave particular focus on EBP, as it is generally fundamentally crucial in clinical research. Black et al (2015) have emphasized on the importance of EBP. As aforementioned under the method section, the studies included in the study, as per the inclusion and exclusion criteria, were published between the years 2013 and 2020. This emphasizes the relevance of the data and findings associated with the studies reviewed. The difference in methodological designs in the studies also enables this study to be more applicable and credible in clinical practice. The strength of evidence within the articles and the type of research designs are the bases for grading research (Polit and Beck, 2012). The studies selected have methodological designs that include meta-analyses, literature reviews and surveys; mixtures of both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. All these consist solely of empirical research, thereby adding credibility and validity of the application of the findings of this study. Finally, the main findings of the studies enabled the researcher to generate the most appropriate themes to be analysed and discussed in the study. The synthesis of findings and generation of themes have been explained below.

3.4 Synthesis of findings

This study adopted a thematic approach for the synthesis of findings of the studies. This section narratively explains the findings of the studies with the aim of interpreting the findings, summarizing the evidence and systematically comparing the variances, characteristics and main features of the study (Moule and Goodman, 2014). The themes generated from the studies include the following: The prevalence of influenza, general vaccine uptake rates and importance, fear of side effects, chronic illnesses, lack of perceived risks, lack of vaccine information, other inconveniences, among others; as will be revealed below.

3.4.1 Influenza as a problem

Across all studies reviewed, one fundamental issue that was clear was the fact that influenza presents itself as a major challenge in the medical sector. Dini et al (2017) describe influenza as an acute but contagious viral infection, having a short incubation period and being mainly spread by droplets. This virus is characterized by feverish symptoms accompanied by systematic as well as respiratory symptoms such as headaches, fatigue and body aches. The study further highlights that influenza A is the most common of the types of influenza. Influenza A is prone to antigenic shifts, thereby representing the most likely type of influenza to cause severe illnesses. Jessop et al (2017) have described seasonal influenza as an important public health issue that often causes the development of acute illnesses in high-risk population and non-immune individuals, and even possible death to them. Influenza also imposes economic burdens because of work absenteeism and sicknesses. Depending on several conditions and factors, the influenza course can be mild or severe. The overall burden of the disease is heavy, on societal, epidemiological and clinical terms (Dini et al, 2017). Shrikrishna et al (2015) present that during a mild season; around 23% of HCWs may become infected with influenza. The study adds that 28-59% of these numbers will have subclinical illness. They can therefore act as vectors of transmission to the patients, colleagues, and families. Rogers et al (2018) highlight that influenza is a potentially deadly virus with seasonal peaks. Dini et al (2017) summarily state that HCWs cannot only acquire the virus, but they can also spread it to vulnerable patients. Various variables should be taken into account in looking at influenza as a problem in relation to HCWs; the first is the scope of HCWs within the context of different countries; and the other is the economic variables, which take into account low-resource contexts, where there is shortage of HCWs. The results in this study generally depict an increased risk among HCWs, with a pooled rate of prevalence of 6.3%.

3.4.2 Importance and uptake of the influenza vaccine

In the prevention of influenza, vaccines remain to be the most effective tool, despite the availability of antiviral drugs, which can be administered for both preventive and therapeutic purposes against influenza (Dini et al, 2017). In order to protect hospital staff, their patients and families, Jessop et al (2017) state that it is recommended that healthcare workers are vaccinated against seasonal influenza. Kliner et al (2016) fundamentally begin by highlighting that the UK DH currently recommends that all HCWs that are in direct contact with clients or patients be annually vaccinated against influenza. This is meant to protect not only the HCW, but also his/her family, patients and colleagues. Shrikrishna et al (2015) support the importance of vaccination of HCWs; they highlight that vaccination of the NHS staff helps in reducing the risk of transmitting the virus to the patients, in addition to contracting the virus. Mounier-Jack et al (2020) have stood on the same ground. The study reiterates the fact that HCWs should be considered as a priority group in the vaccination of seasonal influenza. Their findings depicted a wide variation in the vaccines’ uptake within countries. They even add that England achieved a 69.5% vaccination uptake overall in 2017/18 across the community health settings and NHS centres. They even added that the variation in vaccine uptake rates among HCWs in the UK could be associated with a number of factors. Shrikrishna et al (2015) raise concerns on the low uptake rates in England, specifically highlighting that only 54.8% of healthcare workers with direct contact represented the vaccination uptake in England for the 2013/14, which was the last flu season. Stead et al (2018) claim that even though the seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in England has increased over the decade to 68.7% in 2017/18; the national target set of 75% set by the NHS is still higher than the national average. Several factors affect this uptake among HCWs, both on an individual level, and at operational level.

3.4.3 Attitude, knowledge and belief on influenza

Among HCWs, Dini et al (2017) finds that medical doctors generally have a higher knowledge level of influenza, compared to other HCWs. On the same note, knowledge on influenza among dentists was limited. Even though this knowledge has increased over time, many perceptions and misconceptions persist; these varying depending on the category or type of HCWs. Dini et al’s (2017) study also add that seasonal influenza vaccine uptake rises in cases where the HCWs believe that influenza is highly contagious and its prevention is very important. The study also adds that not having had influenza previously, or having the vaccination, point to negative predictors of vaccine uptake. In Rogers et al (2018), 28.9% of the participants who failed to receive the vaccine stated that they did not believe they were in danger of actually contracting the flu. Mounier- Jack et al (2020) also highlight that some of the barriers to acceptance include the belief that the individuals are not at risk of actually contracting the virus.

3.4.4 Perceived risk

Dini et al (2017) associated higher perceived susceptibility to H1N1 influenza virus with the intention and willingness to vaccinate oneself against it. Dini et al (2017) further add that the belief of less risk towards contracting influenza negatively influenced the uptake of the vaccine among HCWs. In Shrikrishna et al (2015), participants who did not receive the vaccine, claimed to feel less at risk of getting the flu. Rogers et al (2018) support this factor by highlighting that the participants who failed to receive the vaccine did not believe that they were in danger of actually contracting the virus. Stead et al (2019) also supports this concept by outlining that the level of perceived risk is also an important factor that affects the variation of the influenza vaccine uptake. Mounier- Jack et al (2020) also bring out the aspect of perceived risk by highlighting that some of the barriers to acceptance include the perception of not being at risk of influenza. This is associated with other factors such as the perceptions on the effectiveness of the vaccine and the lack of faith in the vaccine’s concordance with the virus strain in circulation.

3.4.5 Perceived benefit

Dini et al (2017) found that in a review of 37 studies, the desire to protect family and friends, and self-protection resulted in predictions of vaccine acceptance. The study adds that denial to social benefit among the HCWs leads to a negative vaccine uptake. The findings of Jessop et al (2017) show that the explanations provided by the staff on the reasons as to why they decided to have the vaccines mainly related to protecting others. This included protecting either their own families or patients. Some of the staff decided to take the vaccination because they felt ‘obliged’ to do so. A few of the participants who did not receive the vaccine in Rogers et al (2018) noted that vaccines are too expensive; this points towards a negative predictor of vaccine uptake.

3.4.6 Age and gender

Dini et al (2017) highlight that the likelihood of protection against influenza was also characterised by the male gender, and older age. The uptake rises in cases of older age and people affected by chronic diseases. Rogers et al (2018), note that age, ex, residence, ethnicity/race and access to health insurance are not significantly associated with receiving the vaccine. In this study, majority of the respondents reported to have been encouraged to receive the vaccine (86.6%). Age, specifically, however, was not found to be significantly associated with the receipt of the vaccine.

3.4.7 Beliefs in vaccine effectiveness and safety

Dini et al (2017) found that the concerns that arose regarding the effectiveness and safety of the vaccines resulted into decreased vaccine acceptance. In looking at the perceptions of effectiveness of the vaccine, Dini et al (2017) found that HCWs, who knew that the vaccine was effective, and were willing to prevent the spread of influenza, and also believed in influenza being highly contagious, were more willing to vaccinate against influenza. The study also added that a general negative attitude towards vaccination and lack of knowledge on the impact of vaccination point towards negative vaccine uptakes among HCWs. In Shrikrishna et al (2015), the surveys conducted differed significantly between the group that was vaccinated, and the group that was not. It was clear that the group that was vaccinated praised the effectiveness of the vaccine; these individuals were of the view that the HCWs should receive vaccination each year. Participants who believed in the effectiveness of the vaccine were even more confident in advising others to get the vaccines. On the contrary, the HCWs who did not receive the vaccine, noted a number of reasons as to why they did not do so; one of them being the perception that taking the vaccine would make them feel unwell. Doctors, however, tended to disagree with this perception made by other healthcare staff. In Mounier- Jack et al’s (2020) study, some of these factors have also been found to affect the rate of influenza vaccine uptake. The researchers found that low uptake among HCWs include the fear of side effects, perceptions on the lack of vaccine effectiveness and the lack of faith in the vaccine; in that, the vaccine may not be concordant with the virus strain in circulation. Jessop et al (2017), while conducting a survey on the reasons behind vaccine uptake among HCWs in the UK, found that one of the themes that arose on the negative predictors of vaccine uptake was the possibility of experiencing side effects and the concerns that the HCWs had on the effectiveness of the vaccine. In this study, only 39% of the participants reported to have not received the influenza vaccination. In addition to this, several misconceptions about the influenza vaccination were also reported to be the reason as to why some of the staff failed to be vaccinated. Some staff did not believe that the vaccine actually worked, whereas some only believed that receiving the vaccine would give the influenza. Similarly, in Rogers et al’s (2018) study, a percentage of the respondents that failed to receive the vaccine were concerned that because of the shot, they would actually be susceptible to influenza. The study also raised issues of the safety of the vaccine with 30.4% of its respondents believing that the vaccines may actually have dangerous side effects. According to Stead et al (2019), on an individual level, the concerns of safety, together with the attitudes toward the vaccination, can be linked with the variation in uptake of the vaccine. The study also outlines the knowledge and attitude towards the vaccine as a factor that influences vaccine uptake among HCWs in the UK.

3.4.8 Social support, external factors and encouragement

Dini et al (2017) state that HCWs vaccination against influenza can also be greatly associated with colleague support, encouragement and recommendation. A HCW is encouraged to vaccinate against influenza upon receiving adequate information and knowledge from official sources, or receiving recommendations from respected HCWs on the vaccination uptake. In looking at the impact of the influence of peers and social networks on vaccine acceptance among HCWs, Dini et al (2017) found that there are links depending on whether the influencer is of the same professional category, age, department/ward, and sex. Furthermore, the study adds that low social pressure; either perceived or real; is a negative predictor of vaccine uptake. In support of this ideology, Rogers et al (2018) also found that in cases where the individual is not informed of the importance of the vaccine, they are not encouraged to receive it. In this study, 9.1% of the participants also cited that they did believe in vaccines for either cultural or religious reasons. Two factors significantly stood out in their association with receipt of seasonal influenza vaccinations: being encouraged by relatives, friends and parents, and having seen a medical provider on the issue within the last few months. Mounier-Jack et al (2020) focused on the organizational factors that would affecting vaccination of staff in NHS acute hospital trusts in England. They found that the culture of an organization is also a very important ingredient in the variation of vaccine uptakes in different organizations or settings. In cases where the vaccination is embedded in the wellbeing strategy of the organization, performance in the delivery and receiving of vaccines was higher. According to Stead et al (2019), on an organizational level, the variation in uptake can be generated by the policy in place, for instance whether the organization adopts a voluntary or mandatory approach. The study also adds on a practical perspective, onto which the influenza vaccine uptake is influenced by the way in which the vaccination programmes are implemented. These include the educational strategies used in addressing the concerns and misconceptions on the vaccines. The study further adds that the wide variation in vaccination uptake across England support the basis that there are implementation and organizational factors that play a role in vaccine uptakes among HCWs in the UK.

3.4.9 Lack of opportunity or inconvenience

Jessop et al (2017), in their qualitative surveys, cited some of the reasons for not receiving vaccination by HCWs to include lack of the inconvenience of venue or time when the vaccination was being offered, and the lack of opportunity. According to them, one of the main reasons as to why NHS staff did not get vaccinated was because of poor availability of immunisation sessions. Junior doctors reported the unavailability of the vaccination sessions as one of the reasons as to why they failed to be vaccinated. Dini et al (2017) support this by highlighting that the lack of access to vaccination facilities also point towards negative vaccine uptakes. In Rogers et al (2018), 9.5% of the participants who did not receive the vaccine noted their reason to be the lack of knowledge of where to take the vaccine while 44.9% noted that they did not have the time to receive the vaccines. In contrast to lack of access, which leads to lower vaccine uptakes, in Shrikrishna et al’s (2015) study, participants who received the vaccine, claimed to have easily got the flu vaccination where they worked. Some of the respondents noted that it was too much trouble to actually receive the vaccine, and therefore they did not have the time to receive the vaccine. Stead et al (2019), while looking at the factors that influence the uptake of vaccines at the operational level, state that implementation factors include the real easing of the vaccination, use of incentives, communication strategies and widespread availability of the vaccine to HCWs. In Mounier- Jack et al (2020), some of the factors listed as barriers to acceptance of the vaccine also include needle phobia, constraints related to access to the vaccines, as well as the aspect of inconvenience.

4.0 DISCUSSION

As seen in the results of this review, various factors influence the influenza vaccine uptake rates among HCWs in the UK. Some of the highlighted factors include safety concerns, social support and external factors, lack of access or opportunity, risk perceptions and perceptions or knowledge or belief on influenza. In addition, as highlighted by Stead et al (2019), these factors affect the uptake of the influenza vaccine among HCWs in the UK at different levels: the individual level, implementation/ organizational level, and the operational level. This section expounds on these thematic results and goes further to comparatively analyse other literature, current policies relevant to the research topic. In doing, the researcher takes into consideration the research objectives and questions. This part also highlights the perspectives for future research, recommendations and implications for practice, limitations and strengths of the research and the conclusions drawn from the research. In order to achieve all this, this part is systematically structured in regards to the research questions and the results in chapter 3.

Influenza

Influenza has been echoed to be a problem that causes a significant burden in the medical sector. Dini et al (2017) start by defining influenza as an acute and contagious viral infection. It is spread mainly by droplets and has a short incubation period. The viral infection can also be characterized by feverish/ chills, accompanied by systematic and respiratory symptoms such as muscle and body aches (Dini et al, 2017). The WHO described this infection as an important public health issue, which causes illnesses to non-immune people and even death in cases of high-risk populations (WHO, 2014). The global organization also attributed influenza to huge economic impacts due to the workforce being sick and consequent absenteeism. The influenza viruses cause the flu; these are single-stranded, negative-sense viruses that belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family. There are three types of influenza viruses: influenza A, B and C. The former two have the ability to cause seasonal epidemics among humans. Influenza A, in particular, is the most common type of circulating influenza virus; it is prone to antigenic shifts and represents the most common type that causes severe illnesses (Gasparini et al, 2014). Lee et al (2012) highlight that the WHO declared the novel influenza A (H1N1) outbreak as a pandemic in 2009. The UK had experienced over 470 deaths by the end of the 2009/10 influenza season. The over 65-year age group recorded the highest case-fatality (Health Protection Agency, 2011). According to Yeung et al (2016), the influenza A virus disproportionately increased hospitalisation, deaths and effects on adults. The viral infection continued to be the most common circulating strain of influenza across Europe, China and North America after the 2009 pandemic. Depending on a number of factors such as the age, seasonal flu strain, comorbidity and immune status, influenza can be either mild or severe. Yeung et al (2016) state that influenza is a self-limiting and mild disease to most healthy adults. Dini et al (2017) express that regardless of this fact, the overall burden of this viral infection is quite heavy; whether in societal, epidemiological and clinical terms. In regards to the weight of this problem, the WHO has estimates that up to 15% of the world population can be affected by annual epidemics. This may cause up to 5 million severe cases and up to 500,000 deaths, with mortality rates ranging from 4-8% in adults during the epidemics, and greater than 10-15% during pandemics (Lee and Ison, 2012). While looking at the factors that affect the vaccine uptake in Australia, Kong et al (2020) support that influenza is an infection that continues to cause significant mortality and morbidity.

Vaccination and Vaccination uptake rates

Lee et al (2012) supports the idea brought about by Dini et al (2017). The study supports that vaccination is the main intervention strategy that can be used to mitigate the influenza pandemic or effects. There are certain groups within the population that should be identified to be at higher risk of contracting the virus. Dini et al (2017) state that the most effective tool for preventing flu is the vaccine; this is in spite of the availability of antiviral drugs that can be administered against influenza for both preventive and therapeutic purposes. These antiviral drugs include neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs). The same concept has been supported in number of other empirical studies (Gasparini et al 2014; Barberis et al, 2016). A number of vaccines exist in regards to the prevention of influenza. They can be divided into two main categories: Live, attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIVs) and inactivated influenza vaccines (Dini et al, 2017). Some of the inactivated influenza vaccines include split-virion vaccines, and subunit vaccines comprising of purified NA and hemagglutinin (HA) proteins. Some deficiencies have been attributed to conventional non-adjuvanted trivalent flu vaccines. These include the suboptimal immunogenicity that mainly affects the elderly, in individuals who are immunocompromised or have severe chronic diseases. Moreover, periodic antigenic drifts may reduce the protection offered by conventional vaccines. This results in a mismatch between the vaccinal viral strains and the circulating strains. During the last few years, major advances have been made in the vaccine manufacture, composition and administration due to the new technologies (Durando et al, 2011). In order to improve the performance of different influenza vaccines, many efforts have been initiated to provide for different vaccine options. These have improved performances and effectiveness of the vaccines in terms of being clinically protected, easy to use, simple and tolerable (Ansaldi et al, 2012). The novel approaches embarked to improve the effectiveness of the vaccines have been developed continually in a bid to increase the rate of uptake among patients, as well as individuals at risk, such as HCWs (Dini et al, 2017). As part of the DH policy on vaccination, it was recommended that HCWs receive H1N1 vaccines in order to protect themselves, their patients and maintain their frontline services during the pandemic; even medical students were offered the vaccine from November 2009 (Lee et al, 2012). According to Jessop et al (2017), each year, the NHS in England launches a seasonal influenza vaccination campaign that specifically targets frontline HCWs. The Public Health England (PHE) monitors the achievement of the target set at 75% vaccination uptake. The vaccination of HCWs has been seen to be effective in reducing absenteeism, protecting the patients against nosocomial infections, preventing seasonal influenza, and subsequently decreasing mortality and morbidity (Lee et al, 2012). According to Kliner et al (2016), the current policy on the influenza vaccination among HCWs is quite clear; as provided for under the Influenza Plan and Annual Influenza Letter of 2015-2016, the patient safety and occupational perspectives are considered. The goal is to protect the HCWs themselves from the viral infection, and to reduce the risk of passing the infection on vulnerable patients (Kliner et al, 2016). Mounier-Jack et al (2020) study that international guidelines tend to recommend vaccination for all frontline HCWs annually. The study adds that in England, flu vaccination should be provided by the employer in order to protect both the HCWs and the people they care for. The seasonal vaccination against influenza reduces the transmission of influenza in healthcare settings (To, 2016). There is also moderate evidence that shows that through vaccination of frontline HCWs, there is reduction in illnesses in patients, especially those who are immunocompromised (Jenkin, 2019). Furthermore, Mounier- Jack continue to support that vaccination of HCWs also prevents absenteeism and staff illnesses, thereby being cost-effective. According to Rogers et al (2018), HCWs represent an especially high-risk population when it comes to the risk of being exposed to the virus. Dini et al (2017) state that HCWs is an umbrella term that consists of a number of people. These include medical doctors, such as general practitioners, paediatricians and specialists; nurses; technicians; porters; cleaners; and other health-allied professionals that are at risk of exposure to respiratory pathogens. To expound further, HCWs, in addition to contracting the infections, they can also spread and transmit them to vulnerable patients (Haviari et al, 2015). The definition of HCWs may be different in different countries. The difference may reflect the discrepancies in the respective country’s political, judicial, cultural and historical factors which directly influence the way the HCWs’ practices are coded (Dini et al, 2017). The variability in definition and scope of HCWs is also dependent on the economic variables. Regardless, there is an increased risk of contracting respiratory pathogens among HCWs, with Lietz et al (2016) finding a pooled rate of 6.3% on influenza across 26 studies. Even though the benefits of receiving the vaccine are clear, the rates of vaccine uptakes have still been disappointingly low. Lee et al (2012) found that the uptake rate in the UK was less than 20% in 2008/09, which was the pre-pandemic year. The same disappointing rates were witnessed across many other countries in Europe. There was a slight increase in these rates during the pandemic year, the HCW seasonal influenza vaccine uptake rates rose from 16.5% to 26.4% in the UK. The pandemic influenza vaccine uptake rate among the HCWs rose to around 40% in the UK. The issues of concern brought about by Lee et al (2012) revolved around the vaccine uptake rates among the HCWs remaining suboptimal. Although one of the factors that can be associated with the increasing figures of the seasonal influenza vaccine uptakes is the H1N1 pandemic, several other factors influence the vaccine uptake rates. Yeung et al (2016) support the idea that the recent pandemic in 2009 possibly shifted perspectives on vaccination. The fact that there are reviews on international epidemiology that reported influenza A disproportionately affecting and increasing hospitalisation and death in adults raised many concerns on the importance of vaccination. This is therefore one of the factors that possibly increased the knowledge and perceptions on influenza and its effect, thereby prompting the importance of vaccination. Jessop et al (2017) record the seasonal influenza vaccination uptake rates of frontline NHS workers in England to be 54.9% in the year 2014/15. They go on to further state that there are wide variations in the uptake rates; for instance, the PHE notes that during that year, only a small number of trusts achieved the national goal set by the NHS. Many of the trusts researched in the study had rates of less than 50% and a few more had uptake rates of less than 40%. The difference in uptake rates have been reported to be because of various issues with the participants coming up with various concerns. According to Dini et al (2017), the vaccination coverage among HCWs in Europe is low in spite of the several recommendations by various health organisations. In regards to adherence to the vaccination, the rates recorded by Bish et al (2011) increased from 13% to 53%. According to La Torre et al (2011), a pooled influenza vaccination rate of around 13% was recorded in Italy from a systematic review of 15 studies and a meta-analysis of six studies. The mean influenza vaccine rates in other European countries such as the UK, France and Germany ranged from 15% to 29%.

Although the UK DH currently recommends the vaccination of HCWs that are in direct contact with clients or patients each year, the policy is not enforced (Kliner et al, 2016). The NHS has set the aspirational target of 75% vaccination coverage among all HCWs. This is for all community and hospital services that have been linked to additional funding (Kliner et al, 2016). In looking at the statistics in the US, the Healthy People 2020 set a target of 90% for HCWs vaccination rates so that the risk of influenza in this high-risk population may be reduced (Rogers et al, 2018). Kilner et al’s (2016) study reports low coverage rates despite the vaccination coverage among HCWs. The figures recorded during the 2015/16 season were 50.6%; and 54.9% during the previous season. On a global level, the seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in HCWs still varies (Mounier-Jack et al, 2020). In 2017/18, the uptake rate recorded was 69.5% in England. According to Mounier-Jack et al (2020), even though this rate is relatively high from a global perspective, the wide variation in the coverage rates across acute hospitals from 50% to 92.3% is masked.

Factors associated with the vaccination uptake rates

Stead et al (2018) divided the several factors influencing the uptake of influenza vaccination among HCWs in a systematic and clearly structured manner. They were of the idea that the factors can be divided into those that affect the uptake on an individual level, those that affect the uptake on an organizational level, and those that affect the uptake rates on practical level or perspective. On an individual level, some of the factors that acted as barriers to the uptake included the sense of employment duty, the lack of perceived risk, concerns about the safety of the vaccine, knowledge and attitudes towards the vaccination, and demographic factors that can be associated with the variation in uptake (Shrikishna et al, 2015). Looking at the organizational level, the main factor attributed to the uptake in influenza vaccination among the HCWs was the policy adopted by the organisation. This is dependent as to whether or not the organisations have adopted a voluntary or mandatory approach towards vaccination of their staff. At the practical or operational level, the rates of uptake of the vaccine are influenced by how the vaccination programmes are initiated or implemented. These factors include the real or perceived ease of accessibility of the vaccine, the use of peer vaccinators in administrating the vaccine, the use of influential members of staff to promote and share the importance of vaccination, the use of incentives, different communication strategies adopted and the widespread availability of the vaccines to HCWs (Hulo et al, 2017; Weber et al, 2016). The findings of Stead et al (2018) seemingly summarize the factors that influence the rate of vaccine uptake among HCWs. Various other studies, as shown, under this sub-section, also expound on these factors in different ways. In systematically presenting the results, Lee et al (2012) also highlight a number of factors that amount to reasons for either accepting or declining the influenza vaccine by HCWs, which contributes to the variation in vaccination uptake rates. There were three main reasons as to why the HCWs would accept the vaccine. The participants who accepted the vaccine pointed out that they accepted because they wanted to decrease the risk of being exposed to the virus, reduce the spread of the infection to patients, and reduce the risk of transmitting the infection to their family members. For a clearer picture, the results of this study, in regards to the main reasons of acceptance have been presented in the figure below.

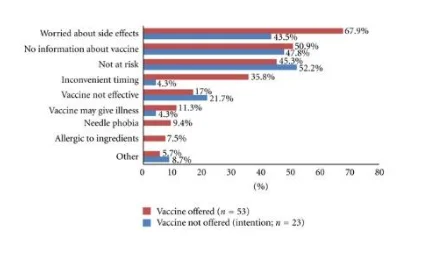

In regards to declination, the main reasons recorded include the perceptions on side effects, the lack of enough information about vaccination, and the low perceptions of risk of exposure. Another reason that was recorded by some of the participants to the survey was the aspect of inconvenience; participants claimed that the timing of the vaccination was inconvenient. A more comprehensive picture of the main reasons of declination, from Lee et al’s (2012) study, has been shown in the diagram below.

In regards to extrinsic factors, three major factors were also reported to influence the uptake of H1N1 vaccine among HCWs: medical training, the recommendations placed by the DH and NHS, and social influences. Interestingly, the social influences cited also included the media (Lee et al, 2012). Another study that supports the findings of this study is Yeung et al’s (2016) study. Yeung et al (2016), while looking at the factors associated with the seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in adults, found that some of the factors include the demography, knowledge and perceptions on influenza and the vaccination, the health behaviour, perception and beliefs, social support and advice, the system of healthcare, and the external environment. On the demographical factors, an important factor to consider is age, this was an important factor associated with the uptake of the vaccination in Europe and Asia (Lin et al, 2010). However, Yeung et al (2016) add that demographic factors such as income, employment, the size of the households and the ethnic origins do not consistently influence the rate of vaccination uptake in different European countries. Prematunge et al (2012) also support the findings of this study. According to their study, the vaccine safety and related adverse effects in HCWs was the main barrier to the pandemic vaccine uptake. The beliefs and attitudes on the vaccine’s safety and other related side effects demonstrated significant differences in the statistics of HCWs who chose to be vaccinated, vis-à-vis those who did not. This factor has been greatly supported by a number of other studies (Torun and Torun, 2010; Alkuwari et al, 2011). In addition, HCW groups that participated and refused to receive the vaccine were not aware of the true incidence of the vaccine relating to adverse events such as Guillain- Barre. In supporting this perceived safety concerns that the vaccines carried, Savas and Tanriverdi (2010) conducted a survey on the measures of anxiety levels in different HCWs. The study found that the state anxiety levels were significantly higher on HCWs who assumed the vaccine unsafe. Another factor that was discussed as a barrier in Prematunge et al (2012) was the rapidity of the development of the vaccine. This can also be attributed to the safety concerns that may arise; the perceptions on the accelerated authorization of the pandemic vaccine may lead to the safety of the vaccine being compromised, hence, refusal (Blasi et al, 2011). Additionally, perceptions on the vaccine’s ineffectiveness was also a barrier to vaccine uptake. Prematunge et al (2012) have highlighted that some of the reasons given for not receiving the vaccine include the vaccination was not an adequate mode for preventing H1N1 infection or protecting against them. This can especially be noted with HCWs who had no history of the vaccination or the infection (Alkuwari et al, 2011). According to Black et al (2014), misconceptions about the vaccine significantly contribute towards the low influenza rates among HCWs. The reasons that were most common, in regards to such misconceptions, were doubts on the effectiveness of the vaccine and the fear of the vaccine causing illnesses, or other safety issues. As clearly put down by Prematunge et al (2012), perceived benefits of the vaccination by HCWs encouraged the increase in vaccination uptake. The study mentions three main perceived benefits: that the vaccine enables the HCW to protect oneself, that the vaccine enables the protection of loved ones, and that the vaccine also enables the protection of the patients. The perceived risk or susceptibility is also another factor that Prematunge et al (2012) support. In their study, they mention that HCWs who perceive to be at risk of actually contracting the virus are more likely to be vaccinated against it, and vice versa. On the same note, individuals who had previously been exposed to the H1N1 virus and believed that as a result, they were less susceptible to re-infection, were more likely to refuse vaccination (Blasi et al, 2011). The perceived severity of the virus is another factor that has been brought to light in Prematunge et al (2012), HCWs who perceive themselves to be at risk of a fatal or severe infection, are more likely to be immunized against it. Similarly, compared to the seasonal flu, HCWs who would believe that the pandemic influenza was a more severe and fatal infection, would be more likely to be vaccinated against it. Concisely, from Bish et al’s (2011) study, higher perceived susceptibility to the viral infection, lower perceived costs of the vaccination and higher perceived severity of the disease could be associated with the intention and willingness to vaccinate oneself against influenza. Additionally, HCWs characterized with the male gender and older age were more likely to vaccinate themselves against the disease. Other predictors of adherence to the vaccination process include beliefs in the vaccination effectiveness and safety, having had influenza or its vaccination in the past and the wish to protect oneself and others. Receiving adequate information and knowledge from official sources, or encouragements and recommendations from other respected HCWs also played a major role in improving the vaccination uptake rates (Dini et al, 2017).

Effectiveness of vaccination against influenza

According to Prematunge et al (2012), an established mode of infection control in health care settings is the vaccination of HCWs. This was particularly important during the H1N1 pandemic of 2009/10 (Fiore et al, 2010). Kuster et al (2011), in the meta-analysis conducted of 29 studies and covering 97 influenza seasons, generally found that influenza immunisation of HCWs is effective in protecting the HCWs and reducing infections; both asymptomatic and symptomatic infections. According to Dini et al (2017), a randomized controlled trial conducted for over three consecutive years, found that the efficacy of the trivalent influenza vaccine in young and healthy HCWs was 89% for influenza B and 88% for influenza A. The vaccine was also found to decrease the cumulative days of febrile respiratory disease and also reduce absenteeism among the HCWs. Almost all studies reviewed in this study have reiterated the importance and effectiveness of influenza vaccination among HCWs. Jessop et al (2017) highlight that it is recommended that HCWs vaccinate against influenza so that they can protect the staff, their patients, and their families. According to Prematunge et al (2012), the maintenance of the quality of life, health and availability of HCWs is an essential component in the preparedness of the health sector. During various pandemics, such as the H1N1 pandemic, and the seasonal epidemics, influenza vaccination is a key strategy used in the protecting of HCWs. The study further highlights that this strategy is effective in such situations as it helps in the prevention and protection of the HCWs, as well as their loved ones, and the patients.

Implications to practice

The achievement of 100% vaccination uptake is impossible for a variety of reasons. It is also important to acknowledge the right of HCWs to decline receiving the vaccination. However, by looking at the views, perceptions and reasons as to why there are barriers to acceptance of these vaccines, it is possible to determine how to improve the effectiveness of the influenza vaccination campaign, as well as the vaccine uptake rates among the HCWs. The evidence presented within this study on the patient, employer and HCWs safety benefits of the influenza vaccination and the factors associated with the rate of influenza vaccine uptake goes a long way in informing clinical practice. Future vaccination uptakes among HCWs, as clearly presented, will practically benefit from a fully transparent laid down process that communicates the underlying rationale, evidence base and effectiveness of the vaccine. It is through understanding these factors on an evidence basis that there can be improvement in the influenza vaccination uptake rates among HCWs in the UK.

Recommendations

After unpicking the different rationales for vaccination and summarizing the evidence base for the studies critically analysed and reviewed in this study, two main policy options can be generated, according to Kliner et al (2016): The first policy advocates for vaccination to all HCWs. An occupational health perspective is taken by this policy. In order for this to be effective, there should be justification through evidence of increased risk of influenza among the staff. HCWs would also, in this regard, require credible, valid and reliable evidence of the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. This would significantly increase the uptake rates of the vaccine. The second policy takes on an employer perspective. High vaccination coverage can be targeted if the vaccine is considered a professional responsibility. Evidence on the impact of the vaccine on certain aspects would be important in this case. HCWs would require reliable evidence on a patient safety perspective, evidence on the reduction of influenza risk to vulnerable patients and the reduction on service disruption and sick leaves, which ultimately affect the economic status of the HCW. According to Lee et al’s (2012) study, it is clear that in order to increase acceptance, it is necessary to make sure that the HCWs feel encouraged to receive the vaccine. The uptake is increased in cases where the HCWs believe that the vaccine decreases the likelihood of acquiring H1N1, reduces transmission to other patients, and decreases the likelihood of transmission to the HCWs’ colleagues and family members. In a systematic review conducted by Corace et al (2016), behaviour change frameworks-based programs were analysed based on their impact in improving influenza vaccine coverage among HCWs. The authors found that positive attitudes relating to the safety and efficacy of the influenza vaccination, perceptions of benefit to self and others, self- efficacy, social-professional norms, perceptions of risk and the cues to action were the main predictors of influenza vaccine uptake rates. In support of the concept of raising awareness on the vaccination of HCWs and its impact on the general population, Yeung et al (2016) highlight that individuals with better knowledge about the vaccination being recommended annually; and to high-risk populations; were more likely to choose to receive the vaccination, compared to those with little knowledge on the same. The same also applied to individuals who were aware of other general information on how influenza can be transmitted and treated. In support of this idea, Shrikrishna et al (2015) conclude that taking into consideration the low rates of influenza vaccine uptake; it is recommended that more has to be done to convey messages and more information on flu vaccination to the healthcare community. The present data may help in the improvement of upcoming vaccination campaigns. In addition to this, Painter et al (2010) states that health educators, health practitioners and physicians are integral when it comes to developing campaigns to improve vaccination uptake among both the general population and the HCWs, improving vaccination education and raising community awareness on this issue. In creating more effective educational plans and materials, it is important to improve our understanding of the perceptions and attitudes towards vaccination as well as the factors that arise in regards to it among HCWs. Improving these perceptions and attitudes would be useful in dispelling myths about the vaccine and spreading the value of vaccine within this population. Jessop et al (2017), in their findings, also suggest that the uptake of vaccines within this population can be improved by ensuring that there is flexibility in the vaccination provision and convenience in the process.

Perspectives for future research

From this discussion, it is clear that a better understanding of the perceptions and reasons behind people’s choices of vaccination will enable us to plan the most appropriate health guides and promote programmes that will improve vaccine coverage among the HCWs and the general population. It is therefore necessary for clinical research to qualitatively focus on the perceptions, views, understandings and knowledge of individuals in relation to either the acceptance or denial of the influenza vaccine. In doing so, the most applicable and viable practices and policies can be formulated, consequently preventing/ managing the spread and effects of influenza on the general population. Just as reiterated in Prematunge et al (2012), future studies should be conducted with the aim of informing the design and development of future pandemic planning processes and development of influenza campaigns. It is therefore crucial to analyse and distinguish between the factors that are unique to the pandemic influenza vaccination and those that are congruent with the uptake of the previous seasonal influenza vaccines.

Strengths of the study

The study’s focus on recently published literature enhances the credibility and validity of the information contained within the research. The articles selected for the review were articles published on or after the year 2013; this enables the study to disseminate the most current information and policies on the research topic. The research conducted also provides a comparative and critical analysis of evidence gathered from various literature. In that regard, the priori design, the rigorous and systematic methodological approach, and critical appraisal of extant empirical studies give the study its strengths.

Limitations of the study

While this study has some strengths, as mentioned above, it is also important that its shortcomings be properly acknowledged. First, as discussed under this chapter, the concept of meaning and scope of HCWs differ depending on the country. Although this research has focused on the meaning and scope of HCWs in the UK, the comparative analysis and discussion on the factors relating to HCWs generally has to be carefully looked at. In addition, most literature reviewed within this study did not distinguish their analyses based on the different HCWs subgroups; for instance looking distinctively at nurses, technicians, medical doctors, paediatricians, among others.

Conclusion

Various studies have examined influenza vaccination rates in different populations. According to Dini et al (2017), in spite of the wide recommendation and a decade of efforts for the vaccination of HCWs across most European countries, the coverage rates of influenza vaccination are still low. Among the many factors that have been discussed in this study, some may argue that the scarcity of knowledge among the HCWs on some topic issues such efficacy profiles of the immunization, the safety issues of the vaccines and the severity or risk of contracting influenza are the main factors that have affected the rates of vaccine uptake among HCWs. It is clear that the educational campaigns focusing on the risks and perceptions associated with the influenza vaccine, benefits of vaccination and reinforcement of the reasons for vaccination should be improved so that the rates of vaccine uptake may be higher among HCWs in the UK and across Europe.

5.0 REFLECTIVE ACCOUNT

Briefly, a reflective account portrays the learning experiences and reflection on a certain event. In this case, the researcher reflects on the study conducted herein. There are numerous models of reflective accounts. Some of these models may be over-simplified, complex, or more prescriptive (Barksby et al, 2015). However, most of these models consist of almost similar stages. This section borrows from the ideology developed by Gibbs (1998) which consists of the following stages:

Description of the event

Identification of feelings in relation to the event

Evaluating the experience

Analysing the experience

Drawing conclusions

Drawing an action plan/ areas of development