Vitamin D Deficiency and Health Risks

Chapter One: Introduction

1.1: Background and Rationale

Vitamin D deficiency is a health problem caused by inadequate exposure to sunlight. Vitamin D is crucial for healthy bones; without this mineral, the body cannot effectually absorb enough calcium, which is vital for bone health. Evidence suggests that overweight and obesity are due to low levels of vitamin D, for instance, Chapuy (1997), argues that a body mass index of 30 and above mostly contain low serum levels of Vitamin D.

Additionally, a study conducted by Pradhan (2019) finds recurrent variations of serum 25(OH) D3 among non-obese men below 50 years was highest. Besides, the study finds a high incidence of Vitamin D deficiency among people with a body mass index of greater or equal to 40.

Vitamin D status in the body is commonly measured by the 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH) D) blood test (Chapuy, 1997).

The average level of Vitamin D is measured as nanograms per millilitre (ng/mL). In this regard, most professionals acknowledge levels between 20 and 40ng/mL (Baki et al. 2016). The examples above are common measurements for the results of these tests.

1. Vitamin D3 optimum status, 25(OH) D of 50 nmol/L.

2. Vitamin D2 insufficiency, 25(OH) D of 25-50 nmol/L.

3. Vitamin D deficiency, 25(OH) D < 25 nmol/L.

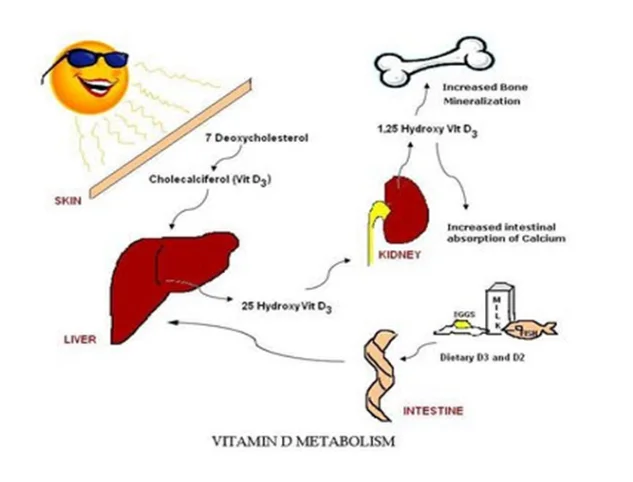

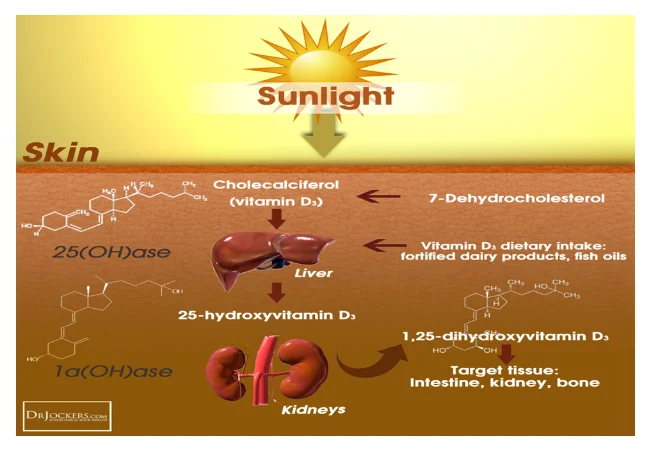

Optimal levels of Vitamin D in the body are essential for human development and optimal body functioning (Thatcher & Clarke 2011). Vitamin D is a group of chemicals or molecules solvable in fat that helps in the hemostasis of calcium (Kirk et al. 2017). The vitamin also is essential in bone metabolism and assists in plays a crucial role in bone metabolism and skeletal mineralisation (Al-Mohaimeed et al. 2012).

Vitamin D occurs in several forms, which include D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5; however, vitamins D2 and vitamin D3 are the essential forms in humans. Vitamin D2, also known as ergocalciferol, is obtained from plant sterols, while vitamin D3, also known as cholecalciferol, can be obtained from fish oils and skin synthesis through UV sunlight radiation (Al-Mohaimeed et al. 2012).

Elsammak et al. (2011) explain that the absorption rate of Vitamin D in the human body is affected by a number of factors, among them are renal function, absorption by the intestines, as well as serum calcium levels and parathyroid hormone. This finding implies that the sufficiency of vitamin D is determined by the accumulation of the vitamin level in the serum by the above human function.

Vitamin D sources include UV Sunlight radiation and foods such as fatty fish, dairy products, cheese, and egg yolks, among others (see figure 1 below) (Al-Faris 2016). However, there have been growing reports of increased deficiencies in vitamin D worldwide. From the literature and stories, women have been reported to be more commonly victims of vitamin D deficiency than men (Thuesen et al. 2012). Studies attribute the higher deficiencies of vitamin D among females to factors such as diet, clothing, and culture (Tsiaras & Weinstock 2011). In a bid to conclusively evaluate these factors, this study examines the vitamin D status of Muslim females in relation to cultural attitudes and practices. This discussion forms the backbone of the study. Islamic teachings on female dress oblige concealing the hair and the body from the ankles to the neck and also the face, which limits the direct exposure of the skin to the sun, which is a vital source of vitamin D (see figure 2).

1.3: Aims and Objectives

The study seeks to achieve the following objectives.

Examine the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency amongst Muslim females.

Examine how various factors including culture, lifestyle, dressing style, and interests in health, affect inadequate sun exposure among Muslim women resulting in an increase in the risk of vitamin D deficiency.

1.4: Hypothesis

The research will be based on the following hypothesis: Different groups of Muslim females have a different prevalence of vitamin D deficiency?

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1: Introduction

This section submits a systematic review of ten key scholarly works. Comparisons shall be drawn between these studies and other academic work in the findings and discussion sections of this study.

2.2: A review of relevant studies

Study 01

Nichols et al. (2012) carried out an investigation to ascertain Vitamin D statuses among non-pregnant ladies of reproductive age in Jordan. Data collection was conducted during the national micronutrient review in Jordan. In their study, Nichols et al. (2012) selected their sample using a complicated multistage stratified cluster sampling method. In their study, Nichols et al. (2012) invited 1992 households to participate in data collection, out of which only 1741 agreed to participate. From the participating families, 2473 females completed the questionnaire, and 2039 also provided a blood specimen. The serum 25(OH) D3 concentrations in the specimens were determined through liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. The authors further determined the incidence rates for deficiency linked to skin covering. Statistical analysis was conducted using binomial regression to establish the factors independently affecting the incidence of vitamin D deficiency. Other statistical analysis methods were also used, including a backward elimination method for all insignificant covariates and calculation of Cramer's V for categorical variables and phi coefficients. After conducting the analysis, the study found that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency varied between groups of women depending on the degree to which clothing covered their bodies. The study pointed out significant variances in the incidence of vitamin D deficiencies associated with the identified factors. 61.7% of women who were clothed with a ‘veil’ had vitamin D deficiency, while 68.0% of those who wore a niqab had vitamin D deficiency, and in those who wore neither a hijab nor a niqab 39.7% had a deficiency. Nichols et al. (2012) established that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was 1.60 times higher for females who covered their bodies with the hijab/scarf, and 1.87 times higher for females who covered their bodies with the niqab compared to women who did not cover the niqab or hijab. The study also identified a significant relationship between an increase in Vitamin D deficiency and an increase in the extent of body cover through clothing. The body cover levels included full body cover including hands and face (excluding eyes) and body cover leaving face and hands uncovered. The study identified that the median 25(OH)D3 concentration among all the 2039 samples analysed was 11.0ng/ml, with an IQR of 9.1-13.5ng/ml. Furthermore, nearly all women, at 95.7%, were vitamin D deficient with a 25(OH)D3 concentration less than 12.0ng/ml.

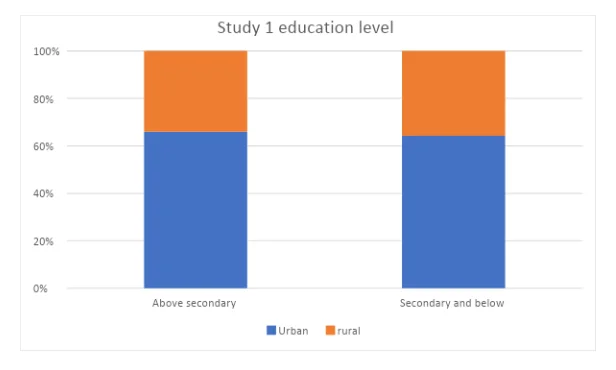

The study also compared vitamin D levels among women living in urban and those in rural areas as well as between different levels of education. Nichols et al. (2014) explain that in their comparison between urban and rural women who completed at least secondary education, urban women had a 1.3 times higher incidence of vitamin D deficiency. Similarly, urban women who had education less than the secondary level had 1.18 times higher rate of Vitamin D deficiency compared to their rural counterparts at the same level. Interestingly, Nichols et al. (2014) explain that among urban women, there were no substantial variances in vitamin D deficiency statuses with respect to education level, with 66.0% of participants who finished at least secondary education being vitamin D deficient compared to 63.1% for those with education below secondary level. However, in rural residency, women who completed secondary education had a 52.5% prevalence compared to 34.8% for those below the secondary education level.

Study 02

Shakir (2012) undertook a survey to measure vitamin D deficiency and social stimuli among Muslim women in Southern. This study utilised a paper survey delivered at Muslim mosques, which are the locations the researcher identified as ideal for quickly accessing the participants, and 101 participants took part in the study. This exploratory study utilised the SPSS for Windows version 18 (2010) software for data analysis and generated a number of outcomes after statistical analysis involving bivariate analysis. The study by Shakir (2011) involved women, most of whom are well educated, which was attributed to their affiliation with Southern Illinois University, with only 5% of the participants having less than secondary level education. The study identified that culture was the major determinant of exposure of the skin in these participants. 78.2% of the participants maintained that they do not expose their skin in public and viewed the exposure of the skin as immodest and contravening of their culture. Furthermore, Shakir (2011) also identifies personal reasons behind the responses of the participants. 50.5% of participants expressed a worry that exposing their skin may cause the sun to darken it. 56.4% of the participants agreed that they are careful when going out in the sun in order to maintain their skin complexion. A further 50% agreed on avoiding skin exposure to prevent their skin from developing wrinkles, while a majority, 85.1%, approved that they cover their skin because of spiritual principles. Among the participants in Shakir’s (2011) study, 42% had vitamin D levels tested, out of which 62% had vitamin D deficiency. Furthermore, the research identifies that among the 26 participants who had vitamin D deficiency, 21 reported having experienced symptoms of vitamin D deficiency, especially body aches, 20 reported having experienced back pains, whereas ten said having suffered bone fractures.

Study 03

Mahmood et al., (2017) evaluates the status of Vitamin D, parathormone (PTH), calcium, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in female garment employees in Bangladesh. Serum specimens were collected from the participants in the case group (female garment workers, n=40) and the control group (general female workers, n=40). Serum vitamin D, parathormone, calcium, and phosphatase were tested by chemiluminescence microparticle immunoassay. The results found that the average level of serum vitamin D was considerably lower in the case group than in the control group. There was no significant disparity in PTH and ALP between the two groups. 100% of the female garment workers had vitamin D deficiency, while 17% of the control group had vitamin D deficiency. This investigation shows a high incidence of vitamin D deficiency among female garment employees in Bangladesh.

Study 04

Elsammak et al. (2011) conducted a study on the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the sunny eastern region of Saudi Arabia. In this study, the participants were drawn from subjects who were coming for check-ups at King Fahd Hospital. The sample was made up of 139 participants, 87 males, and 52 females. The results for female participants only will be reviewed in this section, in line with the objectives of this study. Data were analysed using the SPSS version 10 statistics software. Participants were also asked to fill in a questionnaire, and 93% of females reported having sufficient regular intake of dairy products, and 68% reported having regular exposure to sunlight. Elsammak (2011) used the following ranges for serum 25(OH) D sufficiency; 0-5ng/ml was considered as a deficiency, 5-39ng/ml considered as insufficient, and 40-100ng/ml considered as sufficient. In their analysis, the mean level of serum 25(OH) D in females was 9.9ng/ml.

Study 05

Shah et al. (2013) also sought out to examine the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and to assess the effect of 60,000 IU vitamin D3 sachets in vitamin D deficient ostensibly in fine fettle grownups. Five hundred ten members of health staff at Fortis Hospital in Mumbai were enrolled as participants in the study. Screening for vitamin D deficiency was conducted by Super Religare Laboratories. Radioimmunoassay method was used in the estimation of serum 25(OH) D3. The study presents an analysis of the data collected for 178 participants out of 510 participants who had been enrolled in the study. Those 178 participants consumed the full sachet of supplements for eight weeks, and their vitamin D level was tested afterwards to complete the study. Out of the 178 participants, 120 were female, while 58 were male. Shah et al. (2013) pointed out that prior to the administration of supplements, 94.94% had vitamin D deficiency, while 5.06% had vitamin D insufficiency. Following the administration of vitamin D supplements, however, Shah et al. (2013) report that 78.09% of participants recorded serum 25(OH)D3 level >20ng/ml, up from 5.06% before.

Study 6

Buyukuslu et al. (2014) sought to find the correlation between serum vitamin D levels in a hundred young women and their dressing styles from a young age. The authors investigated this phenomenon using a cross-sectional study that included a hundred female participants (female students) from Istanbul Medipol University. The study employed a survey to collect data. The authors used laboratory tests to determine the levels of serum calcium, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, alkaline phosphatase, and parathyroid hormones. The findings were that the prevalence of vitamin D was 55% for the clothed and 20% for non-clothed participants. The authors concluded that vitamin D levels among young women are associated with their clothing styles, and the age in which they begin wearing them also is correlated.

Study 7

Shefin et al. (2018) also sought to explore vitamin D levels and status among Bangladeshi Muslim women. The study intended to examine the linkage between vitamin D levels and wearing a hijab, whether or not the face was exposed, place of residence, and the amount of sunlight exposure. The study employed a cross-sectional observation method for 353 non-pregnant Muslim Bangladeshi women aged 18 years and above. The study included diabetic participants identified through their clinical history, oral glucose tolerance examination, and those who were already on treatment. The participants were tested for vitamin D statuses with the level of serum 25(OH) D. The study concluded that most of the participants had vitamin D deficiency, which was not directly related to residence status, covering of the face using the hijab, and the level of sun exposure.

Study 8

Another study by Emdadi et al. (2016) intended to examine the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Iranian women. It was a cross-sectional study involving 300 women of reproductive age. Collection of data included participants' demographics such as age (between 15 - 45 years), body mass index, and the serum levels of vitamin D. Serum levels of 25(OH) D were measured by radioimmunoassay. The study found that out of the 300 participants, 257 had deficient levels of vitamin D. 122 of that 257 had a severe deficiency, 96 had moderate levels, and 38 had mild insufficiency.

Study 9

Nimri (2018) conducted a study investigating Vitamin D levels and risk factors among female college students at the American University of Sharjah, UAE. The participants were 480 female students aged between 18 and 26 years. Serum 25(OH)D levels were measured for all participants. The study discovered that 47.92% had suboptimal serum Vitamin D levels, and the risk factors included the kind of lifestyle and avoidance of sun exposure.

Study 10

Al-Yatama et al. (2019) conducted an investigation to determine how covering of the face using hijab among Kuwaiti women affects their serum vitamin D levels, bone marker expression, and bone density. The study divided participants into three groups: unmarried Kuwaiti females aged 20-35 years old who cover their body completely, including face and hands (n=30); a control group who wear westernised clothing; those who wear a hijab but keep their face and hands uncovered. Bone mineral density (BMD), bone markers (procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide [P1NP], osteocalcin, and β-CrossLaps), 25-hydroxyvitamin D, intact parathyroid hormone [iPTH], and calcitonin were measured. The results found that a majority of the participants in all groups had low levels of vitamin D. However, the lowest status was found among the hijab and veiled groups. Therefore, this study concluded that the clothing style contributes to vitamin D deficiency among Kuwaiti women.

2.3: Conclusion

This chapter presented a systematic review of the literature; it adopted a systematic evaluation of various studies identified earlier in the literature search to gather evidence to support the subject matter. A systematic and methodical review of literature ensures that each study is exhaustively reviewed. It is clear that the ten studies examined present a broad scope of perspectives regarding vitamin D deficiency among Muslim females. A comparison of these studies will follow in the findings and discussion sections.

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

3.1 Literature Search

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Google Scholar were used to conduct searches from 2010. This procedure was performed in a systematic fashion as advised by Poeppelbuss et al. (2011) to allow effective and efficient identification of relevant studies to give evidence on the area under investigation. Various search terms linked to the subject heading were employed. They include vitamin D deficiency, the status of vitamin D, Muslim women. The search used Boolean operators, as suggested by Coughlan et al. (2013), to combine the keywords to facilitate filtering down the search process to ensure only relevant literature was found. Peer-reviewed journals (both qualitative and quantitative) were among the criteria used for the search. The author reviewed the search results and evaluated further at the end of the process. A total of twelve studies were found, but only ten were considered for this study.

3.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria involved peer-reviewed literature (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods) linked to the status of vitamin D among female Muslims. All articles from 2010 to 2020, published in English, were included to ensure relevance and validity. Studies published later that 2010 were selected because they contain the most relevant information to provide the logical precision of the study. Besides, modern literature allows the author to follow developments, trends, and ascertain new areas for further research. Conversely, the exclusion criteria entailed abstract-only articles as well as other literature not connected with the subject matter.

3.3 Search Outcome

Initially, the search yielded over 100 articles and literature. These studies were all from databases. The search was refined using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, after which only 12 of them were identified for evaluation; still, the critical appraisal process (CAP) by the author reduced the number to the ten studies which were reviewed in the study.

3.4 Critical Appraisal of Studies’ Quality

This submission employed the CAP approach to assessing the quality of the works of the literature identified. This framework enabled evaluation of the validity of findings, whether the findings can be generalised and the credibility of the research. CAP employs logical arguments, thus increasing the validity of a study. Finally, the studies used in this research were concluded to be of high quality, including the research designs, findings, and ethical considerations employed.

3.5 Data Extraction and Synthesis of Findings

Appendix 1 features a table listing the studies from which data was extracted, which includes the name of the author, year of publication, and the findings for each study. This research involved a review of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research designs. In deriving this study's findings, a narrative methodology was adopted that focuses on interpreting findings, summarising evidence, and comparison of inconsistencies and features between the studies (Moule and Gooman, 2014).

Chapter 4: Findings

4.1 Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency

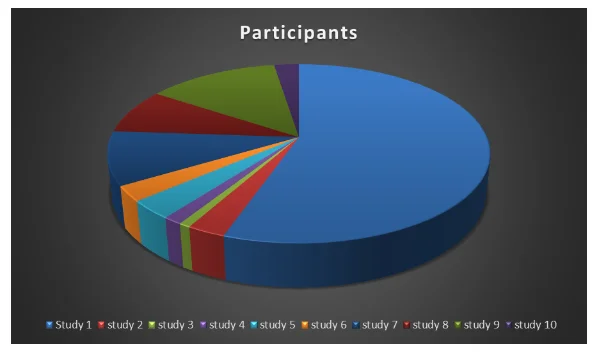

A systematic analysis of the above-selected studies presents interesting results. First, there is a varying participant sample in each individual study. These samples sizes are indicated in Table 1 above are also illustrated in figure 4 below:

60% of the total participants in all the reviewed studies are from study 01, while study four comprised of 0.4% of the total number of participants in all the studies. The number of participants shapes the validity of the results, according to Creswell, (2013) the larger the number of participants, the lower the margin of error, thus study one could have more accurate results than study 4.

4.1.1 Vitamin D deficiency distribution across the studies

The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is shown in figure 3 below. A hundred per cent of participants in study 3 had Vitamin D deficiency. Conversely, study 9 had the lowest percentage for Vitamin D deficiency. Studies 3, 7, and 8 recorded 17%, 100%, and 59% on vitamin D insufficiency among the participants. Other studies did not record this level of vitamin D. In study 04, the mean serum 25(OH) D3 concentration was 9.9ng/ml for females, and in study 05, 94.94% of the participants and 5.06% of participants (both male and female) were vitamin D deficient and insufficient respectively.

4.2 Determinants of Vitamin D Deficiency

The studies point out three key determinants of vitamin D deficiency, as shown in Table 1 above, clothing, level of education, and dietary habits. It is important to reiterate that not all studies presented data for all of the determinants. Clothing appears to be the main determinant of vitamin D deficiency among Muslim females, which is unsurprising considering that the majority of the human body’s vitamin D is synthesised by exposure to sunlight UV radiation. Data on vitamin D deficiency with respect to clothing cover from the ten studies from which clothing cover data was collected is presented in the figures below.

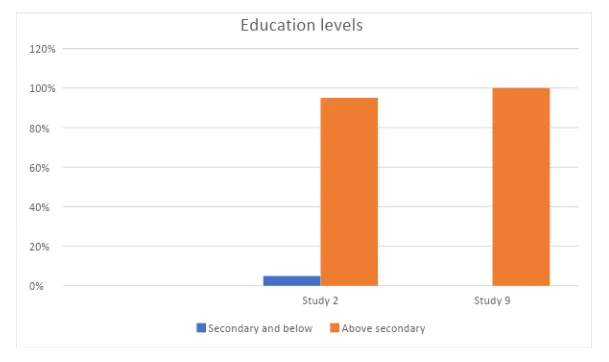

Table 1 presents results on the distribution of scores based on the level of education as a determinant of vitamin D deficiency. There only three studies that discussed education level as one of the determinants in Vitamin D levels (study 1, 2, and 9). Study 01 further distinguishes between urban and rural females to provide a comparison of the results see figure 7.

4.3 Impact of Vitamin D Deficiency

Out of the ten studies undertaken, only one study documented results on the impact of vitamin D deficiency on the body by examining the symptoms experienced by the participants who were identified to have vitamin D deficiency. These outcomes are illustrated in the figure below.

Chapter 5: Discussion and Conclusion

4.1: Introduction

This section seeks to provide a detailed explanation of the findings of the study. This is crucial since it allows for a broader and clearer understanding of the results presented in the study. The comparison of results is conducted with respect to the study objectives. This section provides a detailed analysis and comparison of data with other relevant studies conducted by other researchers.

4.2: Discussion

4.2.1: Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency in Muslim Females

Various studies have concurred that female Muslims generally have a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency compared to their male counterparts (Chailukril 2011). Even though this study focused solely on Muslim females, a study conducted by Elshafie et al. (2012), using a cross-sectional method in Saudi Arabia, concluded that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was 70% for females compared to 40% in males. The authors concluded that the female gender is an independent predictor of vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency, along with their sedentary lifestyles. However, they recommend further discussion on the levels set for the diagnosis of vitamin D levels in the area of study (Saudi). In examining the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, most studies have focused on the Middle East. This is due to the fact that despite the availability of abundant sunlight in this region, Muslim females in these areas higher have a prevalence of vitamin D deficiency compared to females in other countries (Al-Faris 2016; Kotlarczyk et al. 2017). This study has found out that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among females significantly differed from one study to the other. For instance, in study 3, 100% of the participants had vitamin D deficiency levels while study 9, only 48% of the participants had vitamin D deficiency levels. The respective scores have been detailed in the results section above. These disparities could have risen due to possible insufficiencies in the methods employed during the study. For instance, a study conducted by El-Rassi et al. (2009) found that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency ranged between 60-65% in female participants in Lebanon, Jordan, and Iran, while study 01, covered in this research, conducted by Nichols et al. (2014), placed the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among Jordanian women at 95.7%.

4.2.2: Determinants of Vitamin D Deficiency

This study has established key determinant factors that increase the chances of vitamin D deficiency (Jeong et al. 2019). All studies reviewed in this paper have examined the determinants of vitamin D deficiency among Muslim females. From the results tabulated in Table 1 and the analysis visually presented in Figure 2, in the results section above, clothing appears to be the leading factor in causing vitamin D deficiency, and the more the person covers their body, the higher the levels of vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D3 is synthesised using the sun’s UV light radiation, and it is argued that clothing covers the human skin, thus limiting its exposure to the sun and synthesis of the vitamin (Morrissey et al. 2019). Most Muslim females cover their full bodies with clothing due to cultural and religious beliefs that advocate wearing the hijab, niqab, and occasionally gloves. For instance, Studies 1 state that 68.0% of participants who fully covered their bodies were vitamin D deficient, while in study 2, 85.1% of heavily clothed females were vitamin D deficient, and 42%, and 33% were vitamin D deficient in studies 9 and 10 respectively. Some studies have attributed culture and religious practices as the reason why many Muslims have vitamin D deficiency. For instance, study 2 by Shakir further studies why the Muslims do not expose their skin to sunlight, the study finds that Muslims viewed exposure of their skin as immodest and contravening of their culture. Additionally, Shakir identifies other personal responses behind the dress code, such as exposure of their skin to direct sunlight would darken their skin colour. Some respondents argued that they cover their skin to avoid wrinkles. There is, however, no evidence known by the author of this submission that would substantiate the arguments presented by these respondents. However, a majority of them agreed that they cover their body because of religious principles. In studies that have presented comparisons between Muslim females and their male counterparts, there is a small but statistically significant difference in vitamin D deficiency scores. For instance, the study by Mahdy et al. (2010) recorded a mean serum level at 10.3ng/ml for females and 13.7ng/ml for males. Table 1 presented in the results section, for studies 1, 2, and 9, percentages of vitamin D deficient female participants at each level of education are presented. The education level was categorised into two groups; below the secondary level of education and above the secondary level of education. To elaborate on these outcomes, a study by Karthik et al. (2017) examined the awareness of vitamin D deficiency among Muslim females. Out of 220 participants, 46% of the participants expressed being aware of inadequate sun exposure as the cause of vitamin D deficiency, 3% expressed that sunscreen application was the main cause, 7% attributed vitamin D deficiency to dark skin complexion, 14% expressed ageing as the contributory factor and 11% felt that hypertension is one of the factors for vitamin D deficiency.

Elsammak et al. (2011) point out that skin pigmentation (synthesis of vitamin D decreases with darker skin), ageing, use of sun-blocking agents, as well as chronic liver, renal, and gastrointestinal diseases contribute to vitamin D deficiency.

4.2.3: Impact of Vitamin D Deficiency

Out of the ten studies reviewed, only study two collected data on the complications associated with vitamin D deficiency. Tabulated in Table 1 in the results section above, these are manifestations of vitamin D deficiency. Presented in Figure 4 above, 21 (41%) of the participants with vitamin D deficiency complained of body aches, 20 (39%) had back pains, while 10 (20%) experienced bone fractures. Furthermore, Shah et al. (2013) state that complications of vitamin D deficiency include osteoporosis, osteomalacia, muscle weaknesses, and increased risk of falls and fractures.

4.3: Conclusion

This study provided a methodical evaluation of the literature on the vitamin D status of Muslim females. From the statistics examined in this research, it is evident that there are significant proportions of Muslim females that are vitamin D deficient. Consistent predictors of low levels of Vitamin D status include religion and culture, especially clothing, which plays a role in inhibiting skin synthesis of vitamin D from sunlight UV radiation. It is imperative that vitamin D intake is increased, especially among people who are vitamin D deficient in order to avoid health complications associated with the deficiency of the vitamins. Vitamin supplements can be administered to boost levels of vitamin D. Few studies confirm that low-slung socioeconomic status and living in urban settings are predictors of low vitamin D status among Muslim Women. The adverse effects of low vitamin D levels on manifestations of mineral bone uptake are, however, noted in some studies (study 2).

References

- Afkhami-Ardekani, O., Afkhami-Ardekani, A., Namiranian, N., Afkhami-Ardekani, M., & Askari, M. (2019). Prevalence and predictors of vitamin D insufficiency in the adult population of yazd – The sun province in center of Iran. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 13(5), 2843-2847. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2019.07.050

- Ahmed, F., Hasan, N., & Kabir, Y. (1997). Vitamin A deficiency among adolescent female garment factory workers in Bangladesh. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 51(10), 698-702. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600469

- Al-Faris, N. (2016). High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant Saudi women. Nutrients, 8(2), 77

- Allali, F., Aichaoui, S. E., Saoud, B., Maaroufi, H., Abouqal, R., & Hajjaj-Hassouni, N. (2006). The impact of clothing style on bone mineral density among post-menopausal women in Morocco: a case-control study. BMC Public Health, 6(1). doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-135

- Allali, F., El Aichaoui, S., Khazani, H., Benyahia, B., Saoud, B., El Kabbaj, S., … Hajjaj-Hassouni, N. (2009). High Prevalence of Hypovitaminosis D in Morocco: Relationship to Lifestyle, Physical Performance, Bone Markers, and Bone Mineral Density. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 38(6), 444-451. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.01.009

- Al-Mogbel, E. S. (2012). Vitamin D Status among Adult Saudi Females Visiting Primary Health Care Clinics. International Journal of Health Sciences, 6(2), 116-126. doi:10.12816/0005987

- Al-Mohaimeed A, Khan Z N, Naeem Z, and Al-Mogbel E (2012): Vitamin D status among women in the Middle East, Journal of health science 2 (6) 49-56

- Al-Shoha, A., Qiu, S., Palnitkar, S., & Rao, D. (2009). Osteomalacia with Bone Marrow Fibrosis Due to Severe Vitamin D Deficiency After a Gastrointestinal Bypass Operation for Severe Obesity. Endocrine Practice, 15(6), 528-533. doi:10.4158/ep09050.orr

- AlTurki, Y. (2014). Vitamin D deficiency health population overview. Saudi Journal of Sports Medicine, 14(2), 74. doi:10.4103/1319-6308.142348

- Al-Yatama, F. I., AlOtaibi, F., Al-Bader, M. D., & Al-Shoumer, K. A. (2019). The Effect of Clothing on Vitamin D Status, Bone Turnover Markers, and Bone Mineral Density in Young Kuwaiti Females. International journal of endocrinology, 2019.

- Andersen, R., Mølgaard, C., Skovgaard, L. T., Brot, C., Cashman, K. D., Chabros, E., … Ovesen, L. (2005). Teenage girls and elderly women living in northern Europe have low winter vitamin D status. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 59(4), 533-541. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602108

- Andersen, R., Mølgaard, C., Skovgaard, L. T., Brot, C., Cashman, K. D., Jakobsen, J., … Ovesen, L. (2007). Pakistani immigrant children and adults in Denmark have severely low vitamin D status. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 62(5), 625-634. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602753

- Ardawi, M. M., Sibiany, A. M., Bakhsh, T. M., Qari, M. H., & Maimani, A. A. (2011). High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among healthy Saudi Arabian men: relationship to bone mineral density, parathyroid hormone, bone turnover markers, and lifestyle factors. Osteoporosis International, 23(2), 675-686. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1606-1

- Bouillon, R. (2010). Vitamin D: Basic and clinical research in vitamin D, vitamin D analogs and bone health. Bone, 47, S355. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2010.09.049

- Chapuy, M., Preziosi, P., Maamer, M., Arnaud, S., Galan, P., Hercberg, S., & Meunier, P. (1997). Prevalence of Vitamin D Insufficiency in an Adult Normal Population. Osteoporosis International, 7(5), 439-443. doi:10.1007/s001980050030

- Dawson-Hughes, B. (1991). Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Wintertime and Overall Bone Loss in Healthy Postmenopausal Women. Annals of Internal Medicine, 115(7), 505. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-115-7-505

- El-Rassi R, Baliki G and Fulheihan G (2009): Vitamin D status in the Middle East and Africa, American University of Beirut Medical Center, Department of Internal Medicine, Beirut, Lebanon, International Osteoporosis Foundation.

- Farrar, M. D., Kift, R., Felton, S. J., Berry, J. L., Durkin, M. T., Allan, D., … Rhodes, L. E. (2011). Recommended summer sunlight exposure amounts fail to produce sufficient vitamin D status in UK adults of South Asian origin. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 94(5), 1219-1224. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.019976

- Gannagé-Yared, M., Maalouf, G., Khalife, S., Challita, S., Yaghi, Y., Ziade, N., … Chandler, J. (2008). Prevalence and predictors of vitamin D inadequacy amongst Lebanese osteoporotic women. British Journal of Nutrition, 101(4), 487-491. doi:10.1017/s0007114508023404

- Ghosh, J., Ratan Basak, S., Bandyopadhyay, A., & Ratan. (2009). A study on nutritional status among young adult Bengalee females of Kolkata: effect of menarcheal age and per capita income. Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 67(1), 13-20. doi:10.1127/0003-5548/2009/0002

- Guzel, R., Kozanoglu, E., Guler-Uysal, F., Soyupak, S., & Sarpel, T. (2001). Vitamin D Status and Bone Mineral Density of Veiled and Unveiled Turkish Women. Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 10(8), 765-770. doi:10.1089/15246090152636523

- Holick, M. F., Binkley, N. C., Bischoff-Ferrari, H. A., Gordon, C. M., Hanley, D. A., Heaney, R. P., … Weaver, C. M. (2011). Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention of Vitamin D Deficiency: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 96(7), 1911-1930. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0385

- Husain, N., Badie Suliman, A., Abdelrahman, I., Bedri, S., Musa, R., Osman, H., … Agaimy, A. (2019). Vitamin D level and its determinants among Sudanese Women: Does it matter in a sunshine African Country? Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(7), 2389. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_247_19

- Jeong, J. H., Korsiak, J., Papp, E., Shi, J., Gernand, A. D., Al Mahmud, A., & Roth, D. E. (2019). Determinants of Vitamin D Status of Women of Reproductive Age in Dhaka, Bangladesh: Insights from Husband–Wife Comparisons. Current developments in nutrition, 3(11), nzz112

- Lee, S., Park, S., Kim, K., Lee, D., Kim, W., Park, R., & Joo, N. (2012). Effect of Sunlight Exposure on Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration in Women with Vitamin D Deficiency: Using Ambulatory Lux Meter and Sunlight Exposure Questionnaire. Korean Journal of Family Medicine, 33(6), 381. doi:10.4082/kjfm.2012.33.6.381

- Mahmood, S., Rahman, M., Biswas, S. K., Saqueeb, S. N., Zaman, S., Manirujjaman, M., … Ali, N. (2017). Vitamin D and Parathyroid Hormone Status in Female Garment Workers: A Case-Control Study in Bangladesh. BioMed Research International, 2017, 1-7. doi:10.1155/2017/4105375

- Moore, N. L., & Kiebzak, G. M. (2007). Suboptimal vitamin D status is a highly prevalent but treatable condition in both hospitalized patients and the general population. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 19(12), 642-651. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00277.x

- Morrissey, H., Subasinghe, S., Ball, P. A., Lekamwasam, S., &Waidyaratne, E. (2019). Sunlight exposure and serum vitamin D status among community-dwelling healthy women in Sri Lanka

- Nichols EK, Khatib D, Alburto N, Sullivan S et al. (2012): Vitamin D status and determinants of deficiency among non-pregnant Jordanian women of reproductive age, European journal of clinical nutrition, 66, 751-756

- Rahman, A. H., Haque, M. E., Naznin, L., & Ahmed, N. U. (2019). Role of Common Addictive Habits on Hypovitaminosis D among Bangladeshi People. Medicine Today, 31(2), 89-92. doi:10.3329/medtoday.v31i2.41958

- Robinson, B. (n.d.). Determinants of Physical Activity Behavior and Self-efficacy for Exercise among African American Women. doi:10.21007/etd.cghs.2009.0263

- Shah P, Kulkarni S, Narayani S, Sureka D et al (2013): Prevalence Study of Vitamin D Deficiency and to Evaluate the Efficacy of Vitamin D3 Granules 60,000 IU Supplementation in Vitamin D Deficient Apparently Healthy Adults, Indian Journal of clinical practice, vol. 23, 827-832

- Thuesen, B., Husemoen, L., Fenger, M., Jakobsen, J., Schwarz, P., Toft, U., &Linneberg, A. (2012). Determinants of vitamin D status in a general population of Danish adults. Bone, 50(3), 605-610

- Vom Brocke, J., Simons, A., Niehaves, B., Riemer, K., Plattfaut, R., & Cleven, A. (2009, June). Reconstructing the giant: on the importance of rigour in documenting the literature search process. In Ecis (Vol. 9, pp. 2206-2217).

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts