Children’s Sports and Parental Influence

Chapter 1 Introduction

Organised sports for children and the youth has a critical role in the cultural development of any country. Participation in sports by the young children and the youths is attributed to the premises that participation is competitive sports plays a major role in building character and therefore helps the children to learn important life lessons. Sports for children is vital in their development; it helps in the development of physical skills, has fun, improves their self-esteem, plays fair and learns to work in teamwork (Anderson et al., 2003). However, in today’s sports culture, the sport has increasingly become a mega money-making business. Resultantly, children and youth sports have become an environment for investors and adults to be emotionally invested. The environment has adopted the culture of "win at all costs" making it a highly competitive and stressful at both the grassroots and academy levels. The behaviour and attitudes that children learn about sports at a young age are carried to their adult life. As such, adults and investors should have an active and positive role in the development of these children into sportsmanship.

According to (Brackenridge and Rhind, (2014) parents should be involved in their children’s sports life in different ways including providing emotional support, give positive feedback to their children’s performance, attend games to watch their children play, communicate realistic expectations to their children, to encourage their children to talk about their experiences with the team members and the coach and to also show a respectable spectator behaviour. Brackenridge, (2002) however, investigated parent's influence on a child's sports performance looking at it from different aspects. The study observed that on a sports day, it is common to see parents shouting out inappropriately on the side-lines. The shouts are not only directed to their children but also to the coach, teammates, referee, and teachers. In this regard too, according to McCarthy, Jones, and Clark-Carter, (2008), positive parental involvement was reported as the main source of sports participation enjoyment by the youths in sports. These observations form the premises of this study which is focused on determining how much parental involvement affects the sporting experiences and performance of their children.

Research rationale

In a study by Mills et al., (2012), parental involvement was named as the most important factor in the development of an academy player. In this study, coaches interviewed stated that there exists a positive correlation between support by the parents and the probability for a player to progress to professional football level. Parental involvement was however characterised by the coaches as, it may over-inflate the player's ego, also it was found to put pressure the players and to provide inappropriate training advice. As such, coaches noted that supportive involvement is important but it must not be overpowering. The question that arises is, what level of involvement is overpowering and what is supportive? How can be parents be appropriately involved in their children's sports life? And, what are the implications of unhealthy involvement? To acquire answers to these questions, this research was henceforth conducted.

Take a deeper dive into UK Same-Sex Civil Partnership Law with our additional resources.

Research aims and objectives

The aim of this research is to investigate the influence of parent involvement in children's sports life. The study aims to understand the coaches' perspectives on parental involvement and over-involvement on their children's sports life. The research aims to explore literature on the impact of parental involvement in their child’s sports activities.

The objectives of this study are;

To investigate the coaches experience with parental involvement and over involvement on children’s sports life.

To investigate the resultant pressure, on sports children, caused by the involvement of parents in children’s sports.

To determine the ways in which parents can be actively involved in a child's sports life for a positive impact on their performances.

Research method

This study employed a qualitative primary research approach. The study targeted children's football coach. Primary research as Bryman, (2016) notes involves gathering data directly from the research respondents. As such it is important to identify a study sample that is relevant and most suitable for the study. In this study, football coaches formed the most appropriate research subjects because of their direct interactions with both the children and parents. The coaches have a direct role in determining the performance, progress, and development of children sport's wise. As such, the coaches experience any pressure that is put on the young players by their parents and have the most experience about how the involvement of these parents affects how the kid perform in sports.

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Parental involvement leading to pressure

There are issues surrounding parental involvement which lead to parental pressure. Parental pressure is defined as behaviours which symbolize expectations that are high or unattainable in a child athlete’s mind (Leff and Hoyle, 1995). The problem has been that parental involvement in their children sporting activities has caused a lot of pressure on child athletes. Pressure has occurred in behaviours that parents have such as pushing a child athlete to play more or practise at advanced levels. Pressure has also shown in covert behaviours like when a parent looks disappointed after a child shows performance which is poor. Pressure has also been seen to come from extremely controlling parents and over-involvement in their children sporting activities (Wolfenden and Holt, 2005). In qualitative research by Wolfenden and Holt (2005, p. 120), the youth who experience parental pressure are those whose parents are overinvolved as well as have high expectations. Parental over-involvement is very problematic especially in competitions as it results in tension between the child athlete and the parent.

Impact of parental pressure

The impact of parental expectations has been found to rely on the perception of a child athlete of the expectations which their parents have as well as whether the child feels that she or he is living up the demonstrated expectations by the parent (Wolfenden and Holt, 2005). Parental involvement has been described by McCarthy and Jones (2007) in their qualitative survey as a common experience that many child athletes have and is a source of reduced enjoyment in activities of sports. The comments by child athletes in the McCarthy and Jones (2007) survey resulted in the finding that the child athlete can feel more pressure when their parents shout at them while competing. One mixed-method research used derogatory and negative comments as themes for regulating parental behaviour. Negative comments were seen in both tournament observations and participant’s audio diaries. Derogatory comments were looked at as potentially having damaging effects on child athletes. The derogatory comments were found to add more pressure to the children athletes (Holt, Tamminen and Sehn et al., 2008). A parenting style that is controlling, studied by Holt et al. (2009), was done by those parents that were highly involved in the sports participation of their child athletes in a manner which undermined the autonomy of those child athletes. These researchers found that the parenting approach used by controlling parents denied such parents the ability to read the moods of their child athletes. The procedure provided them with control rather than structure. Furthermore, such parents were also not successful in establishing open-bidirectional communication with their young athletes. An additional qualitative survey by Scanlan, Stein, and Ravizza (1991) discovered multiple stress sources from parents on their athletic children such as lectures from their mothers before a competition. Gould et al. (1993) also found similar results when fathers lectured their children after the competition. Scanlan, Stein, and Ravizza (1991) claim that these practises usually included general criticism from parents after the competition especially when the child tried to and failed to satisfy the expectations of their parents. Leff and Hoyle (1995) discovered in their examination of support and parental pressure that child athletes perceived less pressure from their mothers than their fathers.

Continue your exploration of Narration and Style of Written Typography and Text in Animation with our related content.

Additionally, in this study, male child athletes felt more parental pressure than their girl counterparts. In a different study using a smaller sample by Hoyle and Leff (1997), girls perceived more pressure from parents than boys. Lee and MacLean (1997) researched the development of parental involvement using a Sports Questionnaire; child athletes said they experienced extreme levels of directive behaviour and pressure from their parents. In a follow-up study by Wuerth, Lee, and Alfermann (2004), beginner athletes similarly experienced more directive behaviour and parental pressure than skilled athletes. Moreover, the child athletes that disliked pressure from parents did not tolerate much directive behaviour from their parents. The child athletes that liked more pressure from their parents also accepted directive behaviour from their parents. These claims by Lee and MacLean (1997) demonstrate the salience of the perception of child athletes in personal experiences. When a study was conducted on both child athletes and their parents, the fathers were perceived to be putting too much pressure and directive behaviour on them as compared to either the mothers or the child athletes (Wuerth, Lee, and Alfermann, 2004). Kanters, Bocarro, and Casper (2008) found that child athlete perceived more pressure from parents than these parents perceived their behaviour. Many types of research done on athlete families do not relate to support, pressure and involvement. They instead relate to child athlete and parent's view on what sport means in their lives. For instance, a study by DeFrancesco and Johnson (1997) measured losing and winning of tennis players. The study also measured sustained effort in the competition and the demonstrated embarrassing behaviours by both parents and athletes during a game. Many athletes and almost all parents in the study claimed that winning was critical for them. A small number of parents and athletes said they felt upset after their children lost to their opponents if the children put considerable effort in the match. Therefore, sustained effort prevented the emergence of negative feelings even with a loss. Half of the athletes’ studies claimed they occasionally did something that embarrassed them on the tennis court such as throwing the racket or yelling while a third of the athletes said their parents acted negatively when they lost. While literature has demonstrated that family members, particularly parents, are instrumental in determining the involvement of their children in sports (Orlick and Botterill, 1975; Lewko and Ewing, 1980; Snyder and Sprectzer, 1976), other people also take part (Smoll and Lefebvre, 1979; Seefeldt, 1980).

According to McGuire and Cook (1983), a fine line needs to be established between influence, encouragement, and coercion. Usually, concerning the decision to take part in youth sport, the difference is only in the perceptions and mind of the child. Smith, Zingale, and Coleman (1978) claim that the expectation and pressures are felt or implied while the parents get influenced by both the differential child performance/adult expectancy discrepancies because of socioeconomic status and the external-internal control locus’ personality variables. Parental pressure is often put on children so that they can achieve high performance. However, the pressure causes stress and anxiety to the youngsters. Parents pressurise children in various ways. Some express their desire for their children to attain high performance while others punish their kids physically. Other parents pressurise their children by showing disappointment (Smith, Zingale, and Coleman, 1978). The various ways parents pressurise their children. These two researchers claim that different traditions for behaving differently are also used by parents to pressurise children. Darling and Steinberg (1993) claim that parenting styles are forms of a primary or basic environment within a family. The environment consists of values and attitudes instead of certain parenting behaviours. The parents who are categorised under higher class socioeconomically often wish for their children to attain higher performance. In this type of parents, parental pressure and its effects are usually seen at very early stages of the children’s lives. Under the same situation, male children receive more pressure as compared to their female counterparts while females experience more anxiety and stress levels than male children (Vernal, Campbell and Beasly, 1997). Studies countering the control locus and parental behaviour support the claims that those parents who are flexible, warm, approving, supportive and have consistent disciplines, as well as those who expect their children to be independent at an early age, are more likely to convince or encourage their children’s beliefs in self-control or internal control. These parents are unlike those who are punitive, critical and rejecting (Davis and Phares, 1969). But, little focus has been given to control’s expectancies where situational factors and personality dominate. Ducette and Wolk (1973) elaborate that the factors (situational factors and personality) strongly determine performance variables. An early study by Rotter (1966) that concentrates on the control locus is currently getting more attention particularly by developmental psychologists who examine factors that are linked closely to sports performance pressure expectations. Based on the subject of performance perceptions, it is claimed that an internal subject usually has internal expectancies which the environment can easily be manipulated and that there is a relationship between one's actions and their reinforcements. Ducette and Wolk (1973) argue that an external individual, on the other hand, has expectations of being controlled by other people and usually believe that their efforts result in no rewards.

James and Rotter (1958) found that people that differed in their control expectancies would also perform differently under learning environments. For instance, internal subjects, who expect that there is a correlation between their actions and attained outcomes, often respond to reinforcements adaptively while external subjects do not. Later, Getter (1966) created a hypothesis which claims that internal subjects could have perceptual sensitivity or can take in more data from situations which are ambiguous (Phares, 1968). These people can also use their focus to appropriate cues thus performing effectively. These people are also said to be able to make any eye contact thus deriving more data per eye contact as compared to external subjects. About the reinforcement processes of a child, both external and internal expectancies regulate their performance to either fail or succeed. Baumeister, Hamilton, and Tice (1985) suggest that the private expectancies that are private to a performer, of success, can improve their performance because of self-attribution of efficacy and competence resulting in the increased effort. Additionally, Baumeister, Hamilton, and Tice (1985) say that the expectancy of an audience, of success, can affect performance by exerting more pressure on a performer. Bandura (1977) offers support to the above hypothesis by claiming that the expectancies of success may lead to increased motivation and self-attribution to succeed. Barling and Abel (1983) examined beliefs of self-efficacy and performance in tennis. They concluded that perceived experiences of success are the major behaviour motivators. Their study discovered that those tennis players rated by at least two external judges as being more skilful had more efficacy expectancies. Therefore, an individual with self-attribution show enhanced performance and effort. Bandura (1977) also analysed self-efficacy and claimed that individual efficacy precepts are about individual beliefs that they can execute the required behaviour successfully to achieve a particular outcome. Bandura (1977) thus claim that a change in behaviour is mediated by the same cognitive mechanism where expectations determine the chosen activity, the effort put and their persistence that a performer exerts. Performers who experience external pressures expectancies of success can end up with damaged behaviour. This is because the success audience’ expectancies usually result in performance pressure that can damage performance (Baumeister et al., 1985).

Because of the pressures from parents, athletes usually deal with results of pressures like guilt, lowered self-esteem, and distress (Donnelly, 1993). Parents can also be seen as supportive when they help their child athletes to enjoy sports. On the other hand, they can be looked at as providing excess pre-competition anxiety and pressure (Stein, Raedeke and Glenn, 1999). Fraser-Thomas and Cote (2009) discovered that parents could offer support to their young athletes leading to the enjoyment of the sport. Additionally, a child athlete who gets encouragement from a parent is likely to stay longer in the sport. However, when parents lack justifiable experiences in a similar sport, the child athlete may deny any methodological advice from such a parent (Horn and Horn, 2007). Excessive parental pressure can result in negative impacts on their child’s enjoyment of a sport. Increased parental pressure, on the other hand, has been associated with decreased enjoyment and performance of a sport by a child in a study conducted by Anderson et al. (2003). Various literature also shed light on the differences between the characteristics or traits of Grassroots children and professional children in sports. For instance, research conducted by Lemmink et al. (2004) show that a talented player is usually homogeneous with his or her performance level. These researchers say that the existing techniques used to measure the general characteristics of performance do not detect the variation between sub-elite players such as grassroots athletes and elite child athletes or professional child athletes. According to Reilly et al. (2000), sports scientists usually acknowledge that a first-class performance is a consequence of various factors that advocate a multidimensional approach in examining non-talented and talented players. According to Ericson (1996), an expert performance is common in individuals with prolonged efforts in an attempt to improve their performance, and because engagement in practise (a deliberate one) is not motivating inherently thus the performer needs commitment. Reilly et al. (2000) demonstrated that measure of speed, agility, perceptual skills, and motivation orientation are important talent indicators in sports. These findings are in agreement with the argument of Deshaies et al. (1979) who say that anaerobic power, perceptual skill, motivation, and speed successfully differentiate an elite athlete from a grassroots or sub-elite athlete. According to Elferink-Gemser et al. (2007), non-talented players and those who are talented cannot be differentiated based on the same characteristics of performance which distinguish elite players. The same assessment criteria used on elite or professional players cannot be used for the non-talented and talented players because usually, elite players began engaging the sport at an earlier age and have more experience than their two counterparts. Elferink-Gemser et al. (2007) say that the time needed to be a professional player also leads to the difference they have with non-professional players concerning their characteristics. Elite players can need a shorter time to have better performance traits, unlike grassroots athletes.

Profession child athletes and athletes, in general, are also occasionally affected by problems of masculinising boys in sports. Wykes and Welsh (2008) found aggressive and violent behaviours (rates of between 85 to 95%) committed to men and which are often reported by news outlets. Most of these violent activities that get media attention is particularly crime committed by male professional athletes against their animals, partners, peers, and children. For instance, in 2003, the National Basketball Association player known as Kobe Bryant committed a sex offence (Tuchman and Cabell, 2003). Another case occurred in 2007 by the National Football League quarterback, Michael Vick who was charged with taking part in a gruesome dogfighting offence. Another instance in 2014 is Adrian Peterson, a National Football League player who got arrested for beating his son brutally. The same year, Ray Rice was caught on camera assaulting his girlfriend in an elevator. The last example is another National Football League player Greg Hardy who got arrested after assaulting his girlfriend violently (Bradley and Deery, 2014). The above cases demonstrate some few aggressive and violent acts committed by men within the professional sporting community. According to Oliffe and Phillips (2008), men are generally exposed to norms of masculine gender which emphasise dominance over females, independence, inexpressiveness, emotional strength, competition, success, and aggression. The association that boys and men experience exposes them to adhere to such expectations and norms while communicating implicitly to them not to adhere to or engage in behaviours considered feminine. These norms are not only present in many sports teams but also encourage a mentality of emotional inexpressiveness, competition, and toughness in line with the manhood placed on men and boys (MacArthur and Shields, 2015). This masculinity creates a challenge for those boys who behave in a somewhat different way from what the norms say, as their adult counterparts discriminate or even abuse them because they are different (MacArthur and Shields, 2015).

Organisations involved in children’s sports

Establishing support and advice centres for children who have experienced abuse and harm is important in supporting youth sports. Additionally, the organisations that operate in sports need to come up with strategies to minimise or curb risks of abuse or harm to children. These organisations should also formulate strict guidelines on how coaches, peers, and parents, as well as any other person that interact with children in sports, should behave (the Founders Group, 2014). These organisations should come up with methods of recruiting, training and communicating with both the child athletes as well as other people involved in their sports. To manage these strategies efficiently, the organisations dealing in child sports should learn how to work with all partners to prevent any possibilities of child athlete abuse and helping those who have experienced abuse. Lastly, an organisation working in child sports should put in place evaluation and monitoring mechanisms for their established strategies to confirm whether they are either successful or failing (the Founders Group, 2014). There are other decisive or positive factors in youth sport and children welfare as a whole. According to the CDC (2018), the objective and perceived benefits of taking part in sports for adolescents and children are many and span several domains such as social, physiological and physical development. This CDC (2018) says that sports foster not only energy expenditure but also vigorous body physical activity. The organised sport has been associated with an enhanced breakdown of the vicious inactivity cycle as well as an unhealthy lifestyle as it enhances the expenditure of calories (CDC, 2018).

Conclusion

Moderately involved parents have child athletes with more enjoyment levels and performance as compared to both under-involved and overinvolved parents. Although both the father and the mother can influence a child, it has been demonstrated that fathers push their children harder as compared to the mothers. Fathers are thus likely to make their child athlete work harder and perform at higher levels. However, mothers have been seen to be caring and nurturing concerning their children sporting activities (Wuerth et al., 2004). Research has also demonstrated that anybody can perpetrate or commit a crime in sport including peers, parents and even coaches. Peers mostly commit crimes like hazing and bullying. Even though some athletes can be more susceptible or vulnerable, concerns of safeguarding should be about all athletes regardless of their characteristics as individuals for instance age or gender. The need to regard indirect abuse happens when children see or witness others being abused within the context of sports. Research has shown that stopping violence is crucial for all types of sports. The context that this violence can occur has grown beyond the training environment or competitive environment. Many athletes are now exposed to a different type of abuse known as online abuse which is perpetrated through social media. Moreover, it is vital to consider that children participating in sports can disclose to other people also involved in the sport, their negative experiences that occur outside the sport. Consequently, sports organisations should be ready to offer the needed support and advice. Concerning an athlete as an individual, getting involved in sport can be linked to some various safeguarding concerns associated with the athlete’s well-being and health. These comprise of self-harm, disordered eating, and depression. Omission acts like neglect and failure to act to avoid injury from competition or training are also personal threats which can be as dangerous as commission acts. Sexual harassment and abuse in sport are considered significant relational threats to child athletes that have been identified. Physical abuse, on the other hand, includes inflicting on a young athlete physical injury either through contact like hitting them or by non-contact means such as forced physical exertion. There is also emotional abuse, the biggest concern for safeguarding due to its high prevalence rate in youth sport. It has been reported that at least 75% of 6000 young people go through emotional abuse in an organised sport. In fact, the needs of athletes can become neglected regarding their social psychological, emotional and physical development.

CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY

This qualitative survey research aimed at investigating and identifying the impact of parental influence on children's sports performance. To achieve this, the study focused on parents' pressure on the young football player, parents' involvement in their kids' sports life, and parents' over involvement in the players' sports performance. The objective was to identify the numerous ways the parents' involvement and pressure support the kids' development and progress in football performance and to establish how the involvement and pressure negatively affect the kids' willingness and interest to play. Also, the study was extended to establish the impact of parental influence on the performance of the coach and the team as a whole. To achieve these objectives, the study adopted a subjective approach and as a result, employing a qualitative research approach was the most appropriate. The current study employed a survey research design. A survey research design is used to gather data about a research population using a series of questions in the form of questionnaires or interviews (Bryman, 2016). For this research, design sampling is important when conducting a survey and it involves the technique of subgrouping the selected research population into a sample. The sample population is issued with the questionnaires or interviewed. The findings from the data gathered by the sampled population are generalised to the research population.

This study targeted coaches training children and young players in both grassroots and academy football clubs. The reason for targeting the coaches is that they are most exposed to the interactions between the children they train and their parents. Accordingly, the information that was targeted was primarily subjective as it was based on the coaches' opinions, experiences, and perspectives. For this reason, a qualitative survey was the most appropriate for gathering the information needed to do this study. All data gathered was qualitative making this research qualitative primary research. A qualitative research design is useful in finding out the diversity in opinions of the research subject regarding the research issue. This study was primary research. This research method was the most suitable for this study because to gather personal experiences and opinions, the data and information ought to be collected directly from the research sample. Primary research is important in that it meets the researcher's specific needs because it is designed and conducted by the researcher (Howitt, 2016). In this study, the researcher used interviews to ask specific questions that were uniquely formulated to gather data related to the research problem. Since the research was scheduled to be completed within a short period of time, it was important to identify a small, unique and most relevant sample. For this reason, a sample of five coaches was settled for after approaching twenty coaches. Participation for the twenty coaches who were approached was limited to a time frame and hence the large target since it was expected that since these coaches were mainly busy, only a few would be willing to participate. Also, when approaching the coaches, they were informed that participation would be through responding to unstructured interview questions, the interview would take 10-15 minutes and that interviews would be done at their place of work. Availability was thus important if a coach agreed to participate.

The study employed a simple random simple method. Using this method, all the members of the research population have an equal probability of being chosen (Howitt, 2016). This sampling method is appropriate when small sample size is required from a large target population. A sample from the larger population is randomly selected after an exhaustive list of potential participants is available, participation is then granted by randomly selecting. The participation forms were delivered to the coaches’ offices but response to participate was sent through an email to the researcher. Participation was only allowed for the coaches who signed and returned the participation. The interviews asked 10 open-ended interview questions. The interviews were conducted face-face. This method of interviewing is very effective for gathering in-depth responses (Silverman, 2016). A face-to-face unstructured interview allows the researcher to ask questions besides those predetermined and there the researcher is able to include the interviewees' opinions and attitude. This type of interview allows the interviewer to persuade and engage the respondent and therefore gather complete and most relevant answers (Sekaran and Bougie 2016). An unstructured interview comprises of open-ended questions that provide the interviewee with the room to give their thoughts and opinions as was needed for this study.

For example, one of the questions asked in this study was;

What is your opinion on parent’s over-involvement in their kid’s sports?

What is your experience on the matter of parents putting pressure on their children in sport?

Since these questions have no one response, it is possible that the participant has more than one answer. To control diverting from the right course, all questions were asked by the interviewer who also interrupted and asked questions not originally included in the list of questions to help the interviewee make their points clear. The responses which were recorded in an audio tape were transcribed to get a written record which is easy to access information for analysis. After transcribing, the qualitative data analysis method was employed. This data analysis method allows the researcher to identify themes, provide an explanation and an interpretation of these themes. In particular, this study employed a content data analysis method. Prior to participating in the interviews, they were supplied with the consent forms to sign. To be eligible for participation, the coaches signed the consent form and returned them through an email. Only then were the participants contacted for plans about the day of the interview. The interviews were conducted at the places of work and therefore it was necessary to seek the consent of the participants and to ensure that the process is not intrusive to the extent of causing disruption. Signing the consent form gave the interviewees a right to privacy. They were informed that throughout the interview and in the report writing, their names would not be used or would be anonymously mentioned. Also, the interviewers were informed that the information they provided would be kept confidential and used for this study only. The interviewees were also informed that if they felt or experienced any kind of inconvenience or were uncomfortable, they were free to withdraw or refuse to participate. Participants were also allowed to withhold responding to any questions that they were not comfortable responding. Besides the information availed in the participation form, when conducting the interview, participants were briefed and allowed to ask questions about any concerns and for maximum clarity. Matters explained and conclusions drawn in this study are not to be generalised since they were based on the opinions and experiences of a small sample. Importantly, however, the findings reported in this study provides explorative information that adds to the literature on the research issues as well as provides insight on the impact of parental pressure on young players in football.

CHAPTER 4 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Introduction

This section of the study presents the findings and then offers an in-depth discussion and explanation of the research outcome. The findings are based on the data that was gathered using unstructured interviews. The discussion of the results is based on the themes identified in the research and by the aims and objectives of the study. In support of the explanations offered here, the qualitative data (interview responses) are quoted to show justification for major observations made.

Findings

The interviews were structured into two sections. In the first section, the researcher gathered demographic information about the subjects. Demographic information is used to gather data about the participants involved in research. This data is important in the determination of representativeness by the research sample to the research population. Determining representativeness in research is important for the generalisation of the implications identified by that research. The demographic characteristics are independent variables that are used to determine whom the researcher will survey. In carrying out a survey, however, it is important to filter the demographic questions so that they don’t compromise the confidentiality of the respondents and to also protect them from feeling as though their privacy has been invaded. In this research, four demographic questions were posed to the respondents and are summarises in the sections below.

Age

All the five respondents, who were all coaches were asked what age they were. The following are the results.

Below is the data on age present graphically for easy reading.

As is presented in Table 1 and Figure 1 above, the coaches interviewed were aged between 21 and 33 years of age. 4 out of the five coaches were aged 21 and 22. The importance of the analysis of this data is that it shows that most of the coaches involved in children football are also young and therefore have had the involvement of their parents recently. As such this helps the subjects in responding to the questions of parental involvement and pressure by relating their own experiences to that of their young trainees.

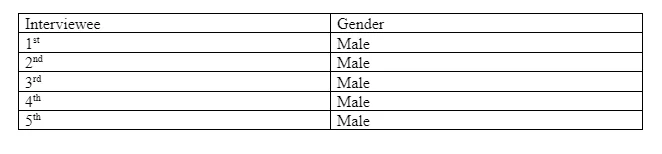

Gender

The respondents were asked to state their ender and the following are the results for this question.

According to the findings in Table 2, all the respondents were male. While this may depict unrepresentative because there are not females represented, it, unfortunately, amplifies the findings of other studies that have reported that football is a men's sports. Gender bias in the world of sport has been re-examined time and again with the aim to establish strategies and regulations that would enable the sport's world to reduce gender bias.

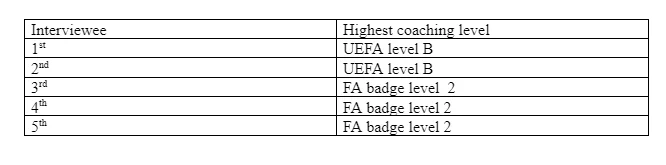

Highest coaching level

All the respondents were asked to state their highest levels of training they have achieved and the following are the results for these questions.

Based on the results in Table 4 above, all the respondent reported to have attained at least FA level 2. Also, based on their responses, all the coaches reported to be en-route to pursue a higher level of training as is visible in the following comments;

1st interviewee

I'm currently doing my UEFA B. I'm just sort of completing my second block. My third block at the end of March-March will be completed by May.

4th interviewee

I'm currently doing my UEFA badges with Nottingham Forest. I've completed my FA badge level two. I'm en-route to keep working up.

These qualifications indicate that the respondents have adequate experience with training children in football and also show enthuse in further expanding their coaching skills. This data shows relevance in terms of the respondent’s selected as well and the information they provided regarding parental influence.

Clubs and Age of Players

All the respondents are asked to state the clubs they had worked for or were working for and also to state the age of players they were training. The following are the responses they provide;

1st interviewee

I currently work at Notts Country's Academy. So, um, I coach the under 9’s to under 16s goalkeepers. So, I, um, I have about 11, 12 goalkeepers during the week to make sure they get the recommended hours.

2nd interviewee

I'm coaching at Notts County at the moment. At the minute I'm covering under 11s. I also do some, um, under 20, under 21s at Nottingham Trent University as well.

3rd interviewee

I currently coach for Cambridge United, um, Football Club. I also am doing in schools camps, and I'm also, like, running in the academies, as well. So that ranges, literally, from the 6 all the way up to about 14, 15-years old, and that is the actual academy itself.

4th interviewee

Currently, I'm at Nottingham Forest. Previously coach a lot of working-class areas clubs around the community. I'm also a freelance coach. I'll go and then coach at kids' parties- and at school holidays and stuff like that so.

5th interviewee

Am now first rated for a team called Vale Juniors. I coach it's kind of under 30.

All the respondents as is clear in their responses have had an experience with coaching children and youths as young as 6 years all the way to under 30. This is a verification that they have adequate experiences with parental involvement in the sports life of children and young football players.

Interview Findings

As highlighted in the method section, the current study employed an unstructured interview comprising of 9 questions. For the sake of analysing and discussing the findings of this study established different themes based on the research objective and this served as a guide to analyse these results. The following are the objectives of this study;

1. To investigate the coaches experience with parental involvement and over involvement on children's sports life.

2. To investigate the resultant pressure caused by the involvement of parents.

3. To determine the ways in which parents can be actively involved in a child's sports life for a positive impact on their performances.

Coaches experience with parental influence on children’s sports life

In line with this theme, the following hypothesis;

The coaches have had experience with parental influence on children's sports activities.

With this hypothesis, the research focused on investigating the evidence of coaches' experience with parental involvement and over involvement based on the responses and from support literature.

Two questions were focused on determining the coaches’ experience with parental involvement. These questions were as follows;

What is your experience on the matter of parents putting pressure on their children in sport?

What is your opinion on parent’s over-involvement in their kid’s sports?

Responding to these questions separately was important as they carry different intense and also reveal different perspectives of the coaches regarding parental involvement. On the first question, all the respondents stated that they had had experience with parental involvement in their children's sports with regard to putting pressure on them. In addition, they all agreed that their experiences were mixed; that is they have seen both positive and negative pressure. In this regard, it was important for the respondents to explain further what each type of pressure means and what actions it comprises. In this regard, all the respondents stated a positive pressure as that which is directed to supporting and encouraging the players to push themselves into doing better. The following are some sample responses to the first question;

1st interviewee

I've had a few experiences when I was younger, I mean playing football from an early age. There was never, uh, any respect barriers, which they are now, there was no rule when I was younger, especially, uh, regarding, uh, parents were allowed to say anything -which is kind of the thing. In our case today, parents must be quiet. Otherwise,-they're sent away, but again, that's controllable, -but something that you can't control is, um, externally, so off the pitch. You-you can't control whether the child's parents are-are gonna put a little bit of pressure on him- at home or in the car going home.

As is clear in this response by the 1st interviewee, as a player in his younger age, he reported that he used to experience pressure from the parent especially because the parents were allowed to say anything without regulations when the game was going on. Although he states that, in the club(s) he works for, the parents are not allowed to shout pressurizing remarks, it is impossible for the club or him as the coach to control what the parent tells the kid off-pitch.

In relation to this question is the second question on over-involvement by the parent. The respondents were also required to give their opinion on their experience on this issue. For this question also, the respondent’s agreed that they have had some experiences where they thought that the parent was over-involved in the kid's sports performance.

The 1st interviewee gave the following answer to this question;

There's been a couple of times where, uh, the coaches have been-- and-and people have questioned it, which is great- but at the end of the day I'm-I'm the coach- and if- Grassroots. They do I mean, even-- I would say grassroots is something you can't control. The-the parents have a massive involvement and again people on the side sometimes think they know more than you.

According to this response, it is clear that the coach agrees that over-involvement is an issue that they have to deal with. In particular, the coach notes that parents' over-involvement not only affects the child but also the coach especially in cases where the parents tend to control what the coach should be doing with the children.

Remarks by the 4th interviewee support this observation;

You get often you get parents coming to you and they say, "Well, my child is not a striker." And you kind of think, "Well, that sounded big headed and boastful." You're thinking, "I'm the one with the qualifications or I mean with this understanding of football." Everyone has opinions about football. It's-it's a matter of subject but yeah, it's-- you often get the same remarks, "My child's not a defender. My child's not a striker." Do you know what I mean?

It is clear that a parent's over-involvement may also have an impact on how the coach does his work. These observations support the findings in Lloyd et al. (2014) where the author established that irrespective of clubs hiring very successful coaches who have been players for big clubs, parents’ over intervening is a serious issue that coaches have to deal with every day. Rhind et al., (2015) claimed that coaches receive messages, emails and calls from parents ranting what they think are not being done right by about their children players. Losing was seen as one on the issue that propels parents to intervene as a way to show the coach what was done wrong and why the team lost. In this regard, Wuerth, Lee and Alfermann, (2004) noted that parents tend to focus on the development of their children individually and as a team in which losing is part of. Parents also were found to intervene on matters of team strategy such as in positioning and team selection among other issues involved with team strategy.

All the other responds were found to support these observations. For example,

The 3rd interviewee stated that

In most cases the over-involvement of the parent leads to a negative impact e.g. when the parent dictates what positions their kids should be playing instead of leaving it to the coach to decide; this reflects disrespect to the coach and may lead to deteriorating confidence of the child and may lead to the child quitting playing football.

Here, the coach also notes the challenge coaches have to face when the parent thinks they are entitled to control what the team is doing. Coaches have to continuously deal with disrespect as parents try to dictate what positions their children should play.

The 2nd interviewee also make similar remarks as follows;

It's the level that I've coached, and from an academy level haven't seen it, but at the grassroots level I've seen parents, you know, really very harsh and almost disrespectful to their own kid, and putting their own kid down if they're not performing to what they, what the parent thinks is a good level of football. And the kid, you can see is really, really, negative, down about playing-playing the game. And you see in training as well, that performance is decreased, they probably don't want to play as much now. They might fake injuries, they might try and walk off a pitch, and-and just, uh, just to stop playing anyway. I have seen it a few times. I've seen it a couple of times. But again, not-not at academy levels maybe I think at grassroots is different.

Besides intervening what the coach is doing at the team’s or club’s level, Raakman, Dorsch and Rhind, (2010) highlighted cases where a parent starts to coach his child off-pitch. For example, Mills et al., (2012) reported a situation where the parent was involved with making his athlete son run an extra five miles prior to team training. The impact of training and coaching a player outside of the team is that the player lacks the free time to relax and sleep. As a result, by the time the player is attending team training, he is already exhausted and will not train or perform in the case of a match. Also, a misunderstanding is likely to develop between the coach and a player who trains alone because the parent and the coach may not necessarily be using the same methods; the player gets confused especially if he is experiencing the pressure to employ the tactics offered by the parent over those by the coach.

In conclusion, the hypothesis;

The coaches have had experience with parental influence on children's sports activities.

Was confirmed and the first objective was achieved.

To investigate the coaches experience with parental involvement and over involvement on children's sports life.

It has been established that the majority on coaches as represented by the sample interviewed have had a personal experience with both parents' pressure on children and over-involvement in the kids' sports performance. It has been established that while parental involvement is important and effective for providing the children with the push they need to propel and grow, over-involvement and negative pressure has the compromising impact of the growth and development of the players' performance as well as on the performance of the coach.

The impact of parental influence on the children sports performance

The impact of parental influence, pressure an involvement on kids performance in football is the second major theme pursued in this research. The theme was pursued using the second objective of the study which is as follows;

To investigate the resultant pressure, on sports children, caused by the involvement of parents.

To achieve this objective, the following two hypotheses were tested;

Parental pressure and involvement have a positive impact on the kids’ sports performance.

Parental pressure and involvement have a negative impact on the kids' sports performance.

To gather data to achieve this objective, participants responded to the following questions

In your opinion, does pressure to perform by parents on their children negatively or positively impact on the child’s sports performance?

What is the influence of parents on their children’s performance in sport based on your experience?

Does pressure by a parent negative impact on a child’s confidence and interest on the sport?

What is your opinion on developing a player’s ego at such an early age?

On sports day, parents are seen shouting from the side-line either to their kids or to the coaches, what impact would this behaviour have on the kid's sports development and performance?

These five questions were organised to bring out the following factors;

Pressure to perform well

Overall parental influence

Child’s confidence and interest

Child’s ego

Parents' side-line behaviour

Asked whether parental pressure negatively or positively impact the child performance, the 3rd interviewee said;

Sometimes negative and other times positive; over-expectation by the parent leads to a negative impact, it prevents the child from enjoying playing football. Encouraging pressure leads to a positive feeling and the child feels appreciated.

Similarly, this interviewer also stated that parental influence either resulted in a negative impact or a positive impact. He reported that;

Positive influence will be attained if the parent supports the child, it makes the child courageous, negative influence will be felt if the parent does not appreciate and support the child.

Similar responses were given by the other coaches

For instance;

1st interviewee

I'll say—the impact depends on how you portray the pressure. Obviously, you can tell with the tone of voice or-- what-what the parent is trying to say on the side-line. I mean that, again, watching grassroots football- you see it quite a lot there.

2nd interviewee

Putting pressure on them I think has a-has a negative. Especially for me being a coach, I want my players to play a certain way of football. Especially an academy on a young-young level. Um, I think the parent's input sometimes can put the kids off. And when you say the word pressure I think it can-it can decrease the performance of the players. Yeah, I think there's good pressure as well. There's good pressure. It definitely depends on the the-the individual kid and the way that the-the, the way that a parent puts that message across. If it can be a little bit aggressive then it can come off negative to a player.

Looking at these responses, it is clear that the coaches think that positive critique is a good force for making the players push harder and perform better. Also, it is clear that since the players are different and as such will perceive critique differently. All the coaches agreed that negative pressure will affect the courage of the player and will fail to perform. These observations support the findings in Leff and Hoyle (1995), that particular aspects of parental influence and pressure have a detrimental impact on the development of the young players. Pressure to win by the parents in the most common for young players. In Leff and Hoyle, (1995), it was established that young players perceptions about themselves are shaped by the pressure and influence they get from their parents. Also, the players’ self-esteem, feelings and urge to enjoy the game can be detrimentally affected by unnecessary pressure and over-involvement by the parents. The participants were also asked to give their opinions on the specifics in terms of positivity and negativity that results from pressure from the parent. With this regard, the coaches were also asked to comment on their opinions regarding the players' confidence and interest to the player as influenced by parental pressure.

5th interviewee

I think parents have a positive influence on children in so many aspects. So, they end up like the portion they want them to try to use sports, and that's what it's all about really. If you don't push kids to do the sport, then they're not going to do it. But you can push them too far then you push them too far, they won't want to play.

4th interviewee

Courage and interest deteriorate. As I said, you've got a child at the age of 13, um, strong development age, um, getting better at football week in week out then you get a comment like that from the parent then they turn around and say, "You know what? I don't want to play anymore." Then you see it they never come back. So, it-it proves heart of the child, it stops-- they never even come back to the club, never mind pursuing that to a career in football.

Besides looking at the players’ interest and courage with regard to how these are affected by the pressure by the parent, the study further looked at how side-line shouts can affect the development and performance of a player. All the respondents agreed that although in most clubs this behaviour is controlled by mandating that no spectator shouts at the players, it is impossible to completely control this behaviour. The respondents agreed that the kids of the parents who keep shouting at the side-line feel embraced and pressured and there has a negative impact on the player’s performance.

Based on the observations made in this section, the two hypotheses were tested and confirmed;

1st Hypothesis; Parental pressure and involvement have a positive impact on the kids’ sports performance.

The study established that positive or realistic pressure and involvement in a child’s sports life has a positive impact on his performance. As noted in Horn and Horn, (2007) a little more push by a parent builds the child’s confidence as he feels supported through the parent’s concern. Also, a little push is important for making the kid feel the competitiveness in a sport and therefore desire to be the best. Besides helping the player’s self-esteem, a positive pressure by the parent makes the child work harder and therefore enjoy the game more.

2nd Hypothesis; Parental pressure and involvement have a negative impact on the kids’ sports performance.

Observations made on the responses provided by the coaches confirmed that parental pressure has a negative impact on the player's performance. A lot of pressure on a child from the parent was identified to make the kid feel as though he was not doing the best or is not playing for himself. As a result, the coaches reported that kids’ will often show disinterest if they cannot handle the pressure coming from the parent. Also, it is impossible for such a kid to enjoy or show development in their sports experience because they always feel as though they are doing it for other people.

This hypothesis hints on the impact of introducing money to young payers. A player’s ego is important as has been observed. It contributes to the player’s courage to play and grow. However a negative ego, especially that which has developed from the urge to be better in the team and to make money. Parents’ pressure is also a major cause for ego because the kids who take the pressure in and decide to please the parents.

Positive parental involvement

The third objective was to determine strategies and ways parents can be actively involved in their children's sports life for a positive outcome. To gather data for this research objective, the participants were asked two questions which were as follows.

What is your advice on parent’s expectations on their children in sports?

In what ways can a parent be actively involved in their kids’ sports life?

The coaches reported that parents are an important part of their training process for the children. Participating in their children's sports life is not only an opportunity for the children to develop sports-wise but also it provides a chance for the parents and children to spend time. Encouraging the kid and showing a positive attitude towards his efforts can have a significant positive influence on the players’ performance, coaches’ and teammates. Also, a positive parental influence has a positive impact on the performance of a team-leading to wins. The participants were asked the different ways they thought parents would be involved and the following are some of the responses;

4th interviewee

A positive involvement in the child’s sports life is important and I advocate the following;

Being present and getting involved in the child’s sports plans and days

Providing a balanced diet

Let the kid watch football and have adequate sleep

3rd Interviewee

I feel like, with diet and things like that, make sure they're sleeping the right amount. So, sleep, diet, massively important. Make sure that you set boundaries. So maybe the child goes to sleep at this sort of time before a game-

All five interviewees stated that positive parental influence would be achieved through general parenting. Parents are a resource to the success of their children and coaches must embrace their participation. The interviewed coaches showed that they acknowledge the resourcefulness of parental involvement. In their responses on the question on advice they have for the parents, the interviewees reported the usefulness of communication between the player and their parents as well as the need for the parent to the only talk of realistic expectations from the kids. Parents must not necessarily be a problem to a coach but rather can be assisting to enable the coach to achieve more.

CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSION

Parenting is the most powerful force affecting the development of children in all aspects and this includes the children’s’ sports development. There are three significant ways that parents affect their kid’s development and these comprise of being the providers, being a role model and being the supporting force that makes the kid believe in themselves. In the current study, the aim was to understand the impact of parental involvement in kid's sports performance. In particular, the study focused on themes related to pressure parents put on their children. The study identified three research objectives that were satisfactorily achieved. The first objective was to investigate the presence of pressure by parents on their kids. The study found out that all the coaches who were interviewed agreed that kids and youths in the sports environment experience a pressure that is then transferred to the coach and the team as a whole. The coaches claimed that they had themselves experienced the pressure as players. The main reasons for the pressure, as noted by the coaches, included the need for the parents to see their children become the best or to play in a winning team. The issue of putting pressure on the kids was found to be fuelled by the fact that the sports environment is today a highly competitive and money making business. For this reason, it matters what club a child plays for, what position the kid plays and how many goals the kid helps the team score. Being the best kid is the only way for the young player to be noticed by large youth professional football clubs and this means more money for the parent and more sports success for the kid. While this is the intended outcome when a parent is putting pressure on their kid, this study found out that the outcome of pressuring a young player is not necessarily positive. In most cases, as was reported by the coaches, a negative impact was experienced. Children who experienced pressure from their parents were reportedly least successful because the pressure demeaned their urge to enjoy to play, their self-esteem, interest to play and confidence to become a better player. Behaviours such as shouting by the side-line, calling and confronting the coach about their kids, shouting to other parents and their kids, private unproductive training their kids and complaining about the team strategies set forward by the coach are some of the issues that were identified as over-involvement on the parent. All these behaviours were found to have a negative impact on the performance of a young player. The coaches also stated that over-involvement resulted in a player quitting or underperforming so that they are eliminated. Therefore, pressure and over-involvement by the parents is a threat to the development and progress of young football talents. However, the study also found out that positive pressure that is aimed at making the kid push harder to become better acted as a motivating factor that was essential for the younger players. The family was found to be of significant support force for children. The study found out that the coaches would advise the parents to be actively involved in their kids' football and sports activities. The coaches reported that parents should act as assistants and not focus on making the coach and the trainers feel as though they were not doing enough. Parental support in the form of emotional support, financial support and information support is highly associated with a positive outcome for kids in sport. Positive pressure from the parents has a positive influence on the kid's perceived confidence, intrinsic motivation to play, coping skills and competencies.

References

Anderson, J. C., Funk, J. B., Elliott, R., & Smith, P. H., 2003. Parental support and pressure and children's extracurricular activities: Relationships with amount of involvement and affective experience of participation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24(2), 241-257.

Brackenridge, C. and Rhind, D., 2014. Child protection in sport: reflections on thirty years of science and activism. Social Sciences, 3(3), pp.326-340.

Baumeister, R. & Showers, C., 1986. A review of paradoxical performance effects: Choking under pressure in sports and mental tests. European Journal of Social Psychology, 16, 361-383.

Baumeister, R.F., Hamilton, J.C. and Tice, D.M., 1985. Public versus private expectancy of success: Confidence booster or performance pressure? Journal of personality and social psychology, 48(6), p.1447.

Barling, J. and Abel, M., 1983. Self-efficacy beliefs and tennis performance. Cognitive therapy and research, 7(3), pp.265-272.

Brackenridge, C.H., Bishopp, D., Moussalli, S. and Tapp, J., 2008. The characteristics of sexual abuse in sport: A multidimensional scaling analysis of events described in media reports. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(4), pp.385-406.

Darling, N. and Steinberg, L., 1993. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological bulletin, 113(3), p.487.

Ducette, J. and Wolk, S., 1973. Cognitive and motivational correlates of generalized expectancies for control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 26(3), p.420.

Elferink-Gemser, M., Visscher, C., Lemmink, K. and Mulder, T., 2004. Relation between multidimensional performance characteristics and level of performance in talented youth field hockey players. Journal of sports sciences, 22(11-12), pp.1053-1063.

Ericsson, K.A., 2000. How experts attain and maintain superior performance: Implications for the enhancement of skilled performance in older individuals. Journal of aging and physical activity, 8(4), pp.366-372.

Fasting, K., Brackenridge, C. and Sundgot-Borgen, J., 2004. Prevalence of sexual harassment among Norwegian female elite athletes in relation to sport type. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 39(4), pp.373-386.

Horn, T. S., & Horn, J. L., 2007. Family influences on children's sport and physical activity participation, behaviour and psychosocial responses. In Handbook of Sport Psychology, Third Edition (edited by G. Tenenbaum & R. C. Eklund), pp. 685-711. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Kavanagh, E.J., 2014. The Dark side of sport: athlete narratives on maltreatment in high performance environments (Doctoral dissertation, Bournemouth University).

Lee, M. J., & MacLean, S., 1997. Sources of parental pressure among age group swimmers. European Journal of Physical Education, 2,

Lloyd, R.S., Oliver, J.L., Faigenbaum, A.D., Myer, G.D. and Croix, M.B.D.S., 2014. Chronological age vs. biological maturation: implications for exercise programming in youth. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 28(5), pp.1454-1464.

McGuire, R.T. and Cook, D.L., 1983. The influence of others and the decision to participate in youth sports. Journal of Sport Behaviour, 6(1), p.9.

Mills, A., Butt, J., Maynard, I. and Harwood, C., 2012. Identifying factors perceived to influence the development of elite youth football academy players. Journal of sports sciences, 30(15), pp.1593-1604.

Rotter, J.B., 1966. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 80(1), p.1.

Reilly, T., Williams, A.M., Nevill, A. and Franks, A., 2000. A multidisciplinary approach to talent identification in soccer. Journal of sports sciences, 18(9), pp.695-702.

Stein, G. L., Raedeke, T. D., & Glenn, S. D., 1999. Children’s perceptions of parent sport involvement: It’s not how much, but to what degree that’s important. Journal of Sport Behaviour, 22(4), 591-601.

Stirling, A.E., 2009. Definition and constituents of maltreatment in sport: establishing a conceptual framework for research practitioners. British journal of sports medicine, 43(14), pp.1091-1099.

Snyder, E.E. and Spreitzer, E., 1976. Correlates of sport participation among adolescent girls. Research Quarterly. American Alliance for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 47(4), pp.804-809.

Smith, M.D., Zingale, S.A. and Coleman, J.M., 1978. The influence of adult expectancy/child performance discrepancies upon children’s self-concepts. American Educational Research Journal, 15(2), pp.259-265.

Tscholl, P., Feddermann, N., Junge, A. and Dvorak, J., 2009. The use and abuse of painkillers in international soccer: data from 6 FIFA tournaments for female and youth players. The American journal of sports medicine, 37(2), pp.260-265.

Wolfenden, L. E., & Holt, N. L., 2005. Talent development in elite junior tennis: Perceptions of players, parents, and coaches. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 17, 108 – 126. Doi: 10.1080/10413200590932416

Sekaran, U. and Bougie, R., 2016. Research methods for business: A skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons.

Howitt, D., 2016. Introduction to qualitative research methods in psychology. Pearson UK.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts